How bad is Guinness 250?

In 1759, Arthur Guinness began brewing beer, if not yet stout, at the St. James’s Gate Brewery in Dublin. He started with an English-style ale and added porter, a lighter antecedent of stout (the original usage was ‘extra stout porter’) in 1778. The porter was so popular that Guinness got out of the ale business in 1799. Guinness had begun brewing stout itself by the beginning of the nineteenth century but the term apparently did not appear in print in Dublin until 1842 (always risky to prove a negative).

Draft Guinness, and the ‘pub draft’ bottled and canned stout, get their unusually rich texture and creamy head from nitrogen rather than the carbon dioxide that forms bubbles in other beers. Another unique feature of Guinness from the outset has been the addition of sour beer to each batch for a tart tone and some depth of flavor. Traditionally Guinness kept old beer on hand for blending in a sort of solera system; prosaic progress has replaced aged wooden casks with a chemical souring process.

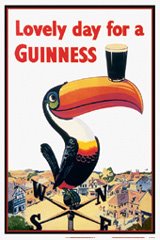

Amidst great fanfare Diageo, the hideously named owner of the venerable Guinness brand since 1997, launched a rather callow campaign this spring to capitalize on the 250th anniversary of the brewery. The lowbrow promotion is an unwelcome innovation probably geared to young drinkers. As Guinness enthusiasts know, its advertising traditionally has been thematically offbeat, visually striking and generally wonderful. Not this time: Take us back to the toucan.

geared to young drinkers. As Guinness enthusiasts know, its advertising traditionally has been thematically offbeat, visually striking and generally wonderful. Not this time: Take us back to the toucan.

Among a number of dubious public relations gambits, Guinness has introduced a special anniversary beer, 250th Anniversary Stout, or ‘Guinness 250,’ that will remain available only until yearend.

The use of a new recipe per se does not break with tradition at Guinness. In exemplary defiance of branding theory, it brews different stouts at different breweries in different countries for different markets. The Guinness you get in Africa is by no means the Guinness you get in Albany or Anglesey. It is, however, unclear why the brewer offers so many unpublicized variations on its famous tradename, which somehow is fittingly perverse and, well, Irish.

Before Guinness closed its Park Royal brewery outside London in 2005, stout sold to the British market was produced there, and in our opinion was inferior to the beer from St. James’s Gate sold in Ireland and exported to the United States. The quality of Guinness in Britain has improved noticeably since then.

According to its website, Guinness also brews stout in over 40 other countries including the Bahamas, Cameroon, Canada, Ghana, Indonesia, Malaysia, Namibia and Nigeria. Alcohol content ranges from 2.8% for a “Guinness Mid-Strength” sold only in boozy Ireland to a whopping 8% for the Foreign Extra Stout of Puritan Singapore. The Editor also has seen a Belgian bottle for “Special Export Stout” from 1995 with “8% alc.” on the label.

A particular product will vary in alcohol as well as taste depending on its market. Traditional bottled Guinness, the ‘Extra Stout’ sold in the United States, has 4.1% alcohol in Germany, 4.2-4.3% elsewhere in Europe and its home market, 4.8% in South Africa, 5% in North America and 6% in Australia and Japan. Unfortunately the excellent Foreign Extra Stout, which itself ranges in alcohol content from 5% to the 8% in Singapore, is unavailable in the United States even though it is distributed in Africa, Asia, the Caribbean and Europe. In all, Guinness is available in more than 150 countries. All of the variants we have sampled are distinctly good.

Only Australia, Singapore and the United States get the Guinness 250; not even Ireland. We might expect the return to tradition for celebrating an ancient anniversary but Guinness has done the opposite; it says (anachronistically) on its packaging that

“This premium recipe takes the flavor of Arthur’s distinctive stout [which did not exist 250 years ago] and balances it with an underlying taste of refreshment, delivering a unique Guinness experience. [Ed: Who, by the way, gets paid to write such awkward drivel and its companion campaign about ‘Arthur’s Day?’ What was wrong with the toucan?]”

Hearts sink: They have lightened it up. This does break with tradition. We ought to have suspected as much based on the markets chosen (but Singapore?) for this ‘underlying taste of refreshment delivering the unique experience.’

We bought some anyway. The anecdotal evidence from bfia’s unscientific and unreliable survey indicates that Guinness 250 has not made much of a splash. We have not found it on tap (they may produce it only in bottles) and virtually none of the beer sellers or bars whose selections we monitor for quality as a service to our readers stocks it. We had to place a special order for our case.

The beer uses carbon dioxide instead of nitrogen and weighs in at a moderate 5% alcohol, presumably intended elements of that underlying taste of refreshment. It has the thin texture of a north German dark like Beck’s or St. Pauli Girl but it is both darker and fizzier. It most definitely is neither a German-style dark nor an English porter in flavor; Guinness 250 is less malty than the darks and not silken like a good porter. Overtones or aftertaste also are more metallic than malty. This beer is both lighter and sweeter than Guinness, probably an attempt to attract the soft drink and cooler crowd, but does evoke memories of the real thing. It is not ‘Guinness Lite,’ however; it is not nearly that bad.

Our tasting panel of an investment analyst, bfia staffers attracted by free booze, college students attracted to the panel for the same reason (including one outlier, a trustafarian) and various other freeloaders reached a consensus: Guinness 250 is a confusing beer. Some liked it more than others but the beer left most of us uneasy. Somehow it manages to be unusual without being distinctive; it is neither unpleasant nor particularly noteworthy. All of us would drink it; few of us would choose it. And yet, after articulating these concerns, the analyst mused “It’s good you know” and none of the panel disagreed. One of the students thought the 250 was good with food, and she had a valid point; the lighter body and less assertive flavor did not overwhelm milder dishes as Guinness itself can do.

Undeniably, however, Guinness 250 is not stout and does not taste particularly like a legitimate Guinness; it lacks the character of the others. If Guinness decides to extend production after all, they should call it something else.

Sadly, Guinness stopped brewing porter back in 1974. Happily, other excellent porters survive, sometimes on a seasonal or otherwise limited basis, both in Britain and the United States. Examples are Fuller’s, St Peter’s and Young’s in Britain; and, in the United States, Abita Turbo Dog, Anchor, Geary’s London Porter, Sierra Nevada, Wasatch (‘Polygamy Porter') and others, including an authentic if challenging sour version from Narragansett (which offers a superb seasonal bock too, both bottled and draft). Sometimes the odd case of Fuller’s London Porter washes ashore in New England, New Jersey or New York even though it is not new.

When the brewing run for Guinness 250 ends, the company ought to revive its porter or, better yet, shift the lines devoted to the undistinguished Harp lager to it and some other dark beer and flog one of them with toucans, who did briefly reappear at Guinness in 2006 for the temporary “Toucan Brew” stout that was sold only in Ireland.

Sources.

-S.R. Dennison and Oliver MacDonagh, Guinness 1886-1939 (Cork 1998)

-Patrick Lynch and John Vaizey, Guinness’s Brewery in the Irish Economy: 1759-1876 (Cambridge 1960)

-Roger Protz, The Ale Trail , (Orpington, Kent 1996)

-South County Beer Bottle Collection LLP