A little salad history

personal and British

My family considers me to be a salad freak. It’s true, I don’t think a meal is a meal without some kind of salad (or at least a very green vegetable) and I annoy them with my nightly entreaties – “would you guys like some salad?” because, as they well know, I certainly would.

I grew up in a time, culture and part of the country where salad was worshipped as an antidote to everything unhealthy. Yes, we girls ate rare cheeseburgers on Long Island in the 1960s, many of us smoked, and we loved to bake in the sun, coated in baby oil and fried with reflectors made of tin foil. But if we wanted to look like Twiggy or Jane Fonda (way before she exhorted us to “feel the burn”) and we did, we turned to salads to rescue us from less healthy practices or excesses. Exercise was not really an option; it involved sweat and muscle development. The salad route was easier. Salads were filling, low in calories, and delicious when well made. One could have one’s cake (or at least celery stuffed with cottage cheese) and eat it too.

I grew up in a time, culture and part of the country where salad was worshipped as an antidote to everything unhealthy. Yes, we girls ate rare cheeseburgers on Long Island in the 1960s, many of us smoked, and we loved to bake in the sun, coated in baby oil and fried with reflectors made of tin foil. But if we wanted to look like Twiggy or Jane Fonda (way before she exhorted us to “feel the burn”) and we did, we turned to salads to rescue us from less healthy practices or excesses. Exercise was not really an option; it involved sweat and muscle development. The salad route was easier. Salads were filling, low in calories, and delicious when well made. One could have one’s cake (or at least celery stuffed with cottage cheese) and eat it too.

All of which is probably why the Editor asked me to write a series of articles on English salads for britishfoodinamerica. What do salads have to do with British food? If you are one of the people still laboring under the misconception that British cooking revolves around badly fried foods (deep fried Mars bars, anyone?), then you will be surprised to learn that Barbara Kafka (famed American food journalist) credits the English in general and John Evelyn’s 1699 book Acetaria: A Discourse of Sallets in particular, with developing our taste for salad over here in the U.S.

"Still, when looking at the broader history of American salad, it's useful to circle back to Europe - to the French (of course), to the Germans (think of potato salad), and perhaps most significantly, to the English. The first English book on the subject of salads was Acetaria: A Discourse of Sallets by John Evelyn, published in 1699. It is remarkably comprehensive, and also prescient of trends to come centuries later, in that it lists the health-giving properties of various greens." (Saveur, May 2007, 57)

I did circle back to check out John Evelyn. He wrote about everything, from architecture to religion, from medicine to Restoration English politics. In Acetaria (which means “sallets, or herbs mixed with vinegar to stir up appetite”) he provides tons of plant descriptions and prescriptions, loads of gardening tips (a veritable Martha Stewart of his day), a diatribe against meat-eating (“unnatural”) and in favor of a frugal, vegetable based diet. He does not mention exercise as healthy, so I guess he might have agreed with my 1960s salad cure-all approach. He ends the book with a bunch of salad recipes which he coyly pretends he received from “an experience’d housewife” (Oh, come now John, we know you wrote them).

By salad recipes, Evelyn evidently meant pickles. If you look up various vegetables in his recipe Appendix, most say “see pickle”. To compose a salad, you evidently chopped up a bunch of these pickled vegetables, added some chopped walnuts or pine nuts, and served it with “good oyl”, vinegar, perhaps some dried mustard and a hardboiled egg or two. This made the early English veggie lifestyle a year-round possibility.

Typical of these recipes is the following for a mushroom “sallet”, adapted from Acetaria. Although it is listed under “mushrooms”, it is, yet again, a pickle.

Ingredients:

Ingredients:

- 1 quart dry white wine

- 1 quart white wine vinegar

- 3 pints of mushrooms – include a variety: oyster mushrooms, baby portabellas, white mushrooms and any other fresh kinds you can find, cleaned and sliced

- 2 teaspoons mace

- 6 cloves

- 1 Tablespoon nutmeg

- 1 teaspoon white pepper

- The peel of one lemon, grated

- 1 whole peeled onion

- Salt to taste

- Combine the wine, vinegar, mace, cloves and nutmeg in a pot, and boil the mixture until it reduces by half. Let the mixture cool, and strain out the cloves.

- Pour the mixture over the mushrooms, and add the lemon peel, the white pepper and salt to taste.

- Add “if you please a whole raw onion, which take out again when it begins to perish”.

Notes:

This yields a whole mess of pickled mushrooms that will evidently keep a long time. Mr. Evelyn doesn’t say, but I assume you would have to put them in a crock or a glass jar and cover them, as you would any fresh pickle.

Granted, this is quite weird by modern standards. Since we are now lucky enough to be able to obtain fairly fresh (if not particularly local or flavorful) produce year round, and since pickles are not always (never?) what we want in a salad, maybe we should move on to the eighteenth century for a more salad-like English salad.

Here is one for “A Fine Salad” from Elisabeth Ayrton, attributed to an unnamed 18th century manuscript (The Cookery of England, London 1974, 380).

Ingredients:

Ingredients:

- A peeled clove of garlic

- About 4 cups torn, crispy lettuce (red leaf or romaine)

- About 2 cups of croutons

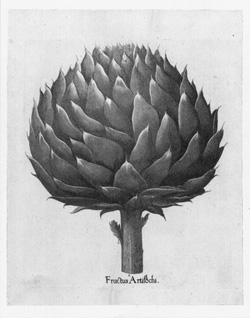

- 4 diced cooked (i.e. canned for us moderns) artichoke bottoms

- About 1 ½ lb. trimmed and cooked asparagus spears

- Vinagrette to taste.

- Rub a plate, or better, salad bowl hard with the garlic clove, spread the croutons on the plate or bowl, throw away the garlic, and let the croutons steep for as much time as you have.

- Toss the lettuce and the artichokes with vinaigrette to taste, toss in the croutons and add the asparagus along with a little more dressing if you like.

Note:

Mrs. Ayrton says to “take four or five” of the asparagus spears “together and stand like little sheaves among the lettuce”. How delightfully English and totally impractical.

But this is more like it. Next time, I promise more British salads from history and from contemporary chefs working in the English tradition.