The rise & rise of rhubarb, including some recommended products.

1. The British reinvent rhubarb.

Rhubarb is one of the crops most closely associated with Britain. It is so entwined with the nations’ foodways that “The English Kitchen” series from Prospect Press examining the “history of cookery in these isles” has devoted an entire volume to it. In Rhubarbaria, Mary Prior maintains that “the British adopted rhubarb with greater enthusiasm, and earlier, than most other countries.” (Prior 34)

Rhubarb is one of the crops most closely associated with Britain. It is so entwined with the nations’ foodways that “The English Kitchen” series from Prospect Press examining the “history of cookery in these isles” has devoted an entire volume to it. In Rhubarbaria, Mary Prior maintains that “the British adopted rhubarb with greater enthusiasm, and earlier, than most other countries.” (Prior 34)

Even so, she notes that “it is a johnny-come-lately to the garden and table.” The plant originated in Asia, where people used it only as a drug for centuries, and it is fitting that this most British crop was transformed by the trading nation into something new.

Various strains of rhubarb, some of which would prove edible and others not, had been imported into Britain from China and elsewhere at least since the fourteenth century for medicinal purposes. (Lemm 2) It commanded a high cost, higher than opium, and traded at the time in France for ten times the price of cinnamon and four times that of saffron. Anyone who could grow it would make a fortune. Apothecaries and botanists in Britain tried to do just that starting in the seventeenth century but without success until almost halfway through the eighteenth. (Lemm 2) Our concern, however is with the edible strains, which it would seem developed by accident.

Prior seems nice enough, and britishfoodinamerica is an admirer of Prospect Books, so it is awkward to confess that her book is a bit of a mess. She claims that the British have been cultivating edible rhubarb “for no more than two centuries” but Hannah Glasse printed a recipe for rhubarb tarts in 1760. As Prior notes, the peripatetic Parson Woodforde recorded eating one in 1793. Woodforde came from sturdy gentry stock rather than the fashionable set and his taste ran to the hearty rather than exotic (he had enjoyed a hashed calf’s head and roast lamb before tucking into the tart) so it is unlikely that rhubarb was not widely known if he was eating it. (Prior 12, 19)

The timing makes sense because it coincides with the increasing availability of Caribbean sugar in Europe. As anyone who has tasted it can attest, unsweetened rhubarb goes considerably beyond bitter.

Elsewhere Prior herself asserts that the fruit “was fashionable in the early nineteenth century.” Later she adds that during its “first years” printed recipes for rhubarb surged “to a flood.” (Prior 11, 26)

She never does give the date when a British grower first successfully cultivated rhubarb for the table. For some reason she quotes interminable passages from the 1911 Encyclopedia Britannica (running to five pages), The Gardener’s Dictionary by Phillip Miller from 1731 (two) and other sources. Then Prior decides that the length of a game-changing eighteenth century letter from Peter Collinson to John Bartram--which she thinks is the first mention of a rhubarb tart in England--“might test the reader’s patience” and therefore fails to reproduce it in full, disclose its date or provide a primary citation to it. (Prior 23-24) Both Collinson and Bartram will loom large in the history of rhubarb cultivation.

She never does give the date when a British grower first successfully cultivated rhubarb for the table. For some reason she quotes interminable passages from the 1911 Encyclopedia Britannica (running to five pages), The Gardener’s Dictionary by Phillip Miller from 1731 (two) and other sources. Then Prior decides that the length of a game-changing eighteenth century letter from Peter Collinson to John Bartram--which she thinks is the first mention of a rhubarb tart in England--“might test the reader’s patience” and therefore fails to reproduce it in full, disclose its date or provide a primary citation to it. (Prior 23-24) Both Collinson and Bartram will loom large in the history of rhubarb cultivation.

Meanwhile, the tart presumably should be the first British mention of the fruit as food but we cannot know because Prior does not say. Next she moves on to James Mounsey, a Scottish doctor in the service of Tsar Peter III (whom Prior misidentifies as Tsar Paul). Among many other things, Mounsey grew and administered rhubarb in St. Petersburg. Following the tsar’s assassination, the new tsarina sacked Mounsey, who quite reasonably feared for his own life and got out of Dodge. Upon returning to Dumfriesshire he

“[m]ade extensive plantations of his new rhubarb…. Many would say that the most significant efforts to reduce the pre-eminence of China stem from this new importation.” (Prior 25)

Poor Peter

Prior discloses the date of the unfortunate tsar’s death in 1762, but not when Mounsey harvested his crop, which in any event was meant for medicinal rather than culinary purposes.

Nothing else in Rhubarbaria serves to draw the timeline of rhubarb in Britain either.

2. Rhubarb in Philadelphia.

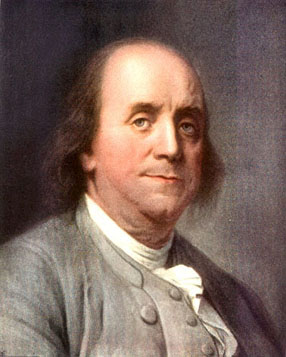

Fortunately, however, an enterprising and scholarly botanist called Joel Fry serves as curator at Bartram’s Garden in Philadelphia. John Bartram is an unfairly forgotten giant from the age of enlightenment who founded the garden that still bears his name in 1728. An autodidact who spent a lifetime pursuing his passion for growing plants, Bartram corresponded with luminaries like Benjamin Franklin and Carolus Linnaeus, who considered him “the greatest natural botanist in the world.” (Duyker 66) Franklin and Bartram, who is best known for introducing North American plants and trees to Europe, founded the American Philosophical Society in 1743.

Apparently unbeknownst to Prior, Collinson was a pivotal figure in enlightenment London. He made his first fortune as a cloth merchant, but also became a member of the Royal Society, botanical enthusiast and philanthropist, instrumental along with Thomas Coram and William Hogarth in establishing the Foundlings’ Hospital for abandoned children. Collinson eventually acted as the distributor of his friend Bartram’s products in Britain. He sent the goods, mostly an astonishing variety of seeds and bulbs in what became famous as “Bartram’s Boxes,” to a large number of customers including Peter Miller at the renowned Chelsea Physic Garden and the Dukes of Argyll, Norfolk and Richmond.

The traffic, however, was not all eastbound. As Fry explains, “[e]arly in the Bartram-Collinson correspondence, probably prior to 1737, Peter Collinson sent John Bartram seeds of a rhubarb…. probably the common garden rhubarb” and then forwarded a second species in 1737. (Fry 1) The two had hoped instead that these were medicinal strains, but Collinson had found them useful anyway and in a letter of 22 September 1739--the one fumbled by Prior--wrote his Philadelphia friend that both “make excellent tarts before most other Fruits fitt for that purpose are ripe.” Collinson also gave him a recipe. (Fry 2)

By then Bartram or possibly Joseph Breintnall, an acquaintance, printer and fellow botanist, already had succeeded in growing rhubarb in Philadelphia; a print by Breintnall from 23 November 1738 documenting rhubarb grown from the seeds sent by Collinson is in the Library Company of Philadelphia collections.

According to the Company, which owns a copy of the 1739 History of London with his extensive annotations, Collinson also “played an enormous role in the life and career of Benjamin Franklin.” (Library Co. 1) The two met in London, where Collinson introduced the American to the Royal Society and piqued his interest in “curious facts relative to electricity.” (Library Co. 2) Franklin received from Collinson equipment for conducting electrical experiments and published their correspondence as Experiments and Observations on Electricity; at least one historian considers him “the most important single person in Franklin’s career.” (Cohen cited in Library Co. 2)

According to the Company, which owns a copy of the 1739 History of London with his extensive annotations, Collinson also “played an enormous role in the life and career of Benjamin Franklin.” (Library Co. 1) The two met in London, where Collinson introduced the American to the Royal Society and piqued his interest in “curious facts relative to electricity.” (Library Co. 2) Franklin received from Collinson equipment for conducting electrical experiments and published their correspondence as Experiments and Observations on Electricity; at least one historian considers him “the most important single person in Franklin’s career.” (Cohen cited in Library Co. 2)

The two remained friends after Franklin returned to Philadelphia. They maintained a correspondence and Collinson served as London agent for the Library Company, which Franklin had founded in 1731, his “historic experiment in democratizing knowledge.” (Library Co. 1) Collinson supplied the library with its first books and convinced it to give Bartram a free membership to

“reflect a great honour on the Society for taking Notice of a Deserving man who has not that effluence of Fortune to be a subscriber But who has a great Genius which may be greatly improved by having a free Access to the Library.” (Library Co. 2)

Franklin and Collinson did not consider their interest in botany secondary to their other vocations: It was equally exciting. The dissemination and ‘improvement’ of plant species were important because more people would gain access to foodstuffs previously unknown to them, food might feed more people and might taste better. Health might improve as well, for the medicinal qualities of various plants were, as we have seen, taken quite seriously.

In January 1770, Franklin, back in London, sent seeds of a third species of rhubarb accompanied by an engraving of the plant, which he considered the “true,” or medicinal, variety to Bartram, who succeeded in growing it along with the others. (Fry 2)

Philadelphia and its hinterland have maintained a close association with rhubarb ever since Bartram’s earliest crops. As the people at Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, a Philadelphia artists’ cooperative, explain, “[i]f you grew up in rural

Pennsylvania, chances are you’ve consumed your share of rhubarb. Pies, teas, jams… for a few months of the year, it seems like it’s everywhere and in everything.” (“Rhuby 1”)

3. Seasons come and go, then vanish.

Rhubarb is not yet in season in Britain. It is the only fruit indigenous to the country that ripens in Winter, and by forcing the plants in heated sheds during the 1870s a resourceful Yorkshireman called Joseph Whitwell was the first farmer who could get stalks to market by Christmas. (Prior 32)

Eventually his neighbors learned the trick. At the peak of production some two hundred Yorkshire growers loaded as much as two hundred tons of produce onto the Rhubarb Express every weekday during the three month season. (Prior 32-33)

The boom chugged along until the Second World War when the Ministry of Food mandated making jam from the crop and then ploughing the roots under to make way for different foodstuffs deemed essential. Roots suitable for forcing take several years to grow, time costs money and meanwhile Britain was inundated with tropical fruits and other exotica starting in the 1950s. The crop was no longer commercially viable. (Prior 33-34)

Rhubarb fell from favor and faded from memory until the advent of the locavore movement and related rediscovery of British foodways toward the end of the century. While rhubarb has returned, the great growers of Yorkshire have not. The last Rhubarb Express left Leeds in 1966 and by 2009 only about ten commercial growers remained in all of Yorkshire.

Whenever it does arrive in British markets, rhubarb is particularly welcomed by devotees of the seasonal. It represents the bridge to Summer berries and Autumn apples, and provides all manner of preserves and preservatives for the Winter to come.

It is remarkably versatile, and suitable for a lot more than sweets. Its tart finish defines one of the oldest English sauces for mackerel and other oily fish.

Our own Rural Correspondent grows rhubarb and makes chutney from it. The Editor’s grandfather grew it too along with strawberries and just about everything else, and her grandmother baked a mean strawberry rhubarb pie.

4. A gazumper.

4. A gazumper.

At least according to Edible Rhody, however, the tart rhizome is harvested in the Fall in New England and, we assume, Pennsylvania. Supermarket supplies bear the assertions out, but these days there is no telling where anything originates. The skewed season may result from the successful effort of Luther Burbank to fool mother nature. He brought reverse rhubarb from the antipodes to America, acclimatized to the southern hemisphere and therefore growing to maturity in the opposite season. His strains “reached the market much earlier than competitors” although, Prior again, we are not told how much earlier or whether Burbank accounts for the Fall crop. (Prior 34)

5. Rhubarb redux.

5. Rhubarb redux.

If not on a par with kale, but fortunately lots more fun, rhubarb is all the rage on both borders of the North Atlantic. Spenser magazine, the hip and glossy startup currently on hold after only five issues, discussed the root last Spring, people grow it on Brooklyn rooftops and the internet abounds with recipes.

Whatever its season, excellent products made from rhubarb are much in evidence at the moment. Farmstead in Providence has started to sell its housemade rhubarb jam, and while the price is steep, the preserve is superb.

Fee Brothers, who produce fifteen types of bitters, include rhubarb among their selections. It is, they say, made from “flavors available in 1800s America” for “an authentic historical taste.” They may be right, but while the Editor is familiar with rhubarb teas and rhubarb shrub, a drink from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, she has found no such earlier reference to rhubarb bitters. She would, however, testify that the Fee Brothers’ bitters taste good and prove versatile.

You can add them to rum and tonic or rum punches, drizzle them into whipped cream, add a tart note to trifle, and boost your rhubarb sauce with an extra layer of flavor in the manner of Paul Prudhomme, who likes to include different iterations of the same ingredient when he can.

Even though the plant shares a genetic root with hops, nobody has done much historically with rhubarb and beer, wine or booze other than the nearly vanished shrub. That now has changed, and provides a reason why the Editor’s thoughts have turned to it during her consideration of Philadelphia foodways.

During the last several years Art in the Age has introduced a number of sweet liquors. Not liqueurs; they are stronger and less cloying than that, in fact not cloying at all. They arrive at eighty proof and show enough sweetness to concoct cocktails without a slug of simple syrup. Root and Snap arise from the German culture of Pennsylvania, Sage and Rhuby from the English. All of them are good on their own or over the merest shard of ice.

Art in the Age distills Rhuby from rhubarb with additional flavorings of beet, cardamom, carrot, lemon and petitgrain, an orange oil. They trace the concept back to William Bartram but ascribe the source of his first seeds to Franklin in 1770. As we know, that distinction goes, four decades earlier, to the forgotten Collinson.

Art in the Age does a lot of other things as well. They mount exhibitions, performances and workshops; sell clothing, housewares and worthy periodicals like “Lucky Peach;” and have a brilliant logo. You can visit them in Philadelphia at 116 North Third Street and online at www.artintheage.com.

Sources:

Anon., The Story of Rhuby (New York 2011)

Bernard Cohen, Benjamin Franklin’s Science (Cambridge MA 1996)

Edward Duyker, Nature’s Argonaut: Daniel Solander 1733-1782 (Melbourne 1988)

Joel Fry, “Did John Bartram introduce rhubarb to North America?” from Growing History: The Philadelphia Historic Plants Consortium (20 July 2012), available at www.growinghistory.wordpress.com.

Elaine Lemm, “Rhubarb: A Brief History of Rhubarb in Britain,” available online through http://britishfoodabout.com.

The Library Company of Philadelphia, “Library Company Acquires Rare 1739 Text Owned by Peter Collinson” (7 June 2012), available at www.librarycompany.org/…/Collinson%20Press20%Release%206-6-12.pdf

Mary Prior, Rhubarbaria: Recipes for Rhubarb (Totnes, Devon 2009)