The duke’s (or devil’s) spawn: Beef Wellington & its twentieth century mutations

It would be difficult to conjure a dish less fashionable in au courant circles than Beef Wellington, a preparation of disputed and, maybe, mysterious origin that had its heyday back in the 1960s. The elaborate dish of beef, foie gras and duxelles encased in pastry was a favorite of Kennedys and Nixon alike, one of the few points of view the antagonists admitted, if only tacitly, to share.

Nothing in print links the dish to the Duke of Wellington, while some authorities date it only to the twentieth century, and then only in American sources. Others, including Jane Grigson, demur. She found a description of the dish, but not by name, in the eighteenth century diaries of James Woodforde. He called it “Beef-stake tarts in turrets of paste.”

It is a difficult dish to cook. Even so, and despite its disputed origin as well as dubious reputation among tastemakers, Beef Wellington has refused to go away. Last January The Economist , not known for the trace of a downmarket readership, included a feature on the dish in its 1843 Magazine , a quarterly topical supplement to the flagship publication. The final season of “Mad Men” appears to have inspired the author: Josie Delap quotes one of the characters exclaiming to his “most explosive of bombshells:”

“Look, we’ve got oysters Rockefeller, beef Wellington, Napoleons… we leave this lunch alone, it’ll take over Europe.”

Down the social scale from Camelot, La Casa Pacifica and the luxury hotels that facilitated the trysts of advertising executives from Madison Avenue during the 60s, less affluent aspirants wanted a whiff of the prestige that accompanied the preparation, so unscrupulous scribblers found ways to deracinate the original dish. It was easy enough to substitute a can of liver pate for the foie gras, ditch the duxelles and specify frozen puff pastry (itself, however, an excellent product), but technique has remained a prohibitive problem for cooks of modest skill.

Beef Wellington would become so ubiquitous that Julia Child felt obliged to include an unironic recipe in The French Chef Cookbook , and not as bouef en croute or any other Gallic construction. Her Mastering the Art of French Cooking , however, includes a variant she labels Filet de Boeuf en Croute with the subtitle “Beef Wellington Brioche” along with the unnecessary observation that “it is certain that the French would not have named it after Wellington.” Even so, she remains uncertain whether the dish originated in England (discounting, perhaps inadvertently, the Scots), Ireland or France.

Whatever its origin, Childs is unequivocal. “It is a remarkably handsome, sumptuous dish when properly made” an “important dish” that “should be surrounded with few distractions.” Her instructions for making beef Wellington properly are among the most complicated recipes in print. The French Chef version requires over two dozen ingredients processed through more than fifty steps across two or three days.

The Art of French Cooking variant is even worse because it is of comparable length and also incorporates several other recipes described elsewhere in the book. Both of the Childs recipes read like the plans for a complicated military operation.

Notwithstanding the naysayers and trendsetters since the era of Childs, celebrity chefs have embraced the old chestnut on television and online. Alton Brown, Jamie Oliver and Gordon Ramsay among many others each post recipes for Beef Wellington, an indication that the dish remains popular with their mainstream audiences if not with the culinary elites.

All these permutations are defensible enough. In fact a well executed Wellington, or Jane Grigson’s version of the eighteenth century beef in turrets that James Woodforde identifies in his diaries, does represent a formidable achievement. The dish looks and tastes good and does impart dinner with a sense of occasion. It is just that it is difficult to execute, as the more baroque recipes of Childs indicate.

Other dishes labelled Wellington are not so defensible. The impostors may be based on fish, lamb, pork, turkey, even, inevitably these days, tofu. Chicken is perhaps the most culpable charlatan. Buffalo, Green Goddess and ‘Tuscan’ are only a few of the Chicken Wellingtons in circulation.

The Food Timeline places the first reference in print to Mumbai (then Bombay) during 1955. It appeared in an advertisement from The Times of India for the enticingly named Eros Restaurant:

“Today’s lunch speciality… Celery Soup, Chicken Wellington or Eggs Curry & Pillaw, Charlotte a la Russe or Eros Ices… Also Tandoori & Punjab Specialities.”

So much for the apocryphal absence of British influence, baleful as it may be in this instance, on Indian foodways.

By 1972, promoters of prepared food had conjured some ghastly apparitions. “With so many developments in the convenience food area,” the Chicago Daily Herald advised its readers, “it takes very little effort today to prepare gourmet dishes we wouldn’t dream of attempting a few years ago.” The Herald’s recipe for Chicken Wellington incorporates “frozen patty shells,” pre-sliced processed ‘Swiss’ cheese and, not a typographical error, canned peaches in heavy syrup.

According to the Los Angeles Times, that same year a local caterer served its Wellington “in the shape of a little chicken. Very elegant.” Perhaps

Peaches are not the only fruit that ill-advised innovators have shoehorned into their versions of the dish. Latzi Wittenberg may have created the most bizarre Wellingtons in name as well as substance a year earlier for the Kosher Food Manufacturers Association convention in New York. His Royal Hawaiian Wellington was made with pineapple and sweetbreads (trafe?!) and he called the one incorporating chopped beef (presumably not trafe) and turkey Rothschild Wellington. “There were some famous Jews in Britain,” Wittenberg ‘explained’ to The New York Times , and I think he’d like to have his name associated with Jewish foods.” It remains unclear whether Wittenberg referred to Rothschild or Wellington but it does not matter much because the rationale is equally risible one way or another.

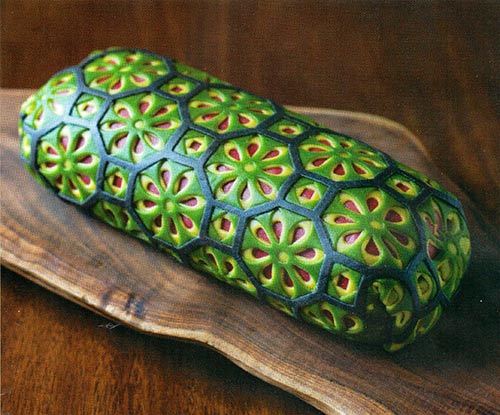

To return to the present, a British chef called Anthony Rush in Honolulu “transforms beef Wellington,” according to the February 2020 issue of Food & Wine , “into a hypnotizing work of edible art” by using various vegetable juices and a couple of suspect substance (hay ash… ) to fashion multiple layers of dyed dough that resemble “intricate patterns inspired by his mother’s quilt work,” yet another example of food porn for the Instagram age. Anyone for Flannel Wellington? Or perhaps Wellingtonian Flannel.

Something like green eggs and ham

Rescue beef Wellington from ignominy by preparing its predecessor, “Steak pies sauced with Madeira.” It is Jane Grigson’s version of the ‘turrets’ that James Woodforde enjoyed in the eighteenth century. You will like it just as much now; the recipe appears in the practical.

Newspaper quotations are taken from The Food Timeline , www.foodtimeline.org/foodmeats.html#beefwellington (accessed 27 January 2020)