A maelstrom of food, sex & death featuring a few British derivations.

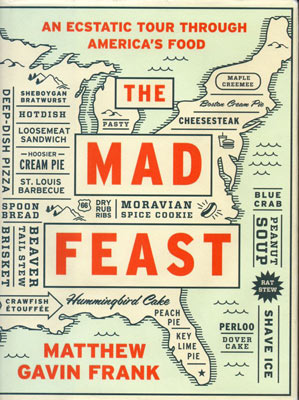

Even its most enthusiastic adherents must admit that The Mad Feast: An Ecstatic Tour through America’s Food is as mad as the culinary cultures it purports to chronicle. The ecstasy is akin to religious delirium rather than secular joy.

The author of the book, Mathew Gavin Frank, chooses a recipe from each of the fifty United States and proceeds to offer his own idiosyncratic fantasy of its origin and development. In reality Frank is at least as interested in ranting about sex and death as in delving into the history of food, although he does have a preoccupation with cream of mushroom soup and La Choy fried onions. If the effect of his approach is disorienting it does not lack entertainment value.

The selection for Minnesota is one of a number of recipes with a pronounced but unremarked British derivation. The “Bulldog Tater Tot Hotdish,” named for the restaurant of the chef who gave Frank the recipe, braises chunked brisket in beer and wine like a London cook. Then Minnesota practice sandwiches the stew between tater tots and a topping of caramelized Brussels sprouts sauced in mushroom white sauce.

Frank informs us that during the Minnesota winter, an uncle tells him that he would like to hang “something from every fruit tree that now, in this kind of weather, bears no fruit. He wants, we think at first, to remind himself of Bounty.”

What is the connection to Hotdish? It turns out to be quite clear. Frank explains that because the uncle is “muttering through a mouthful of Hotdish, we can’t tell if he wants to hang a can of soup, or a can of corn, or the last piece of unground meat he saw years ago, or the last fresh potato, or his own dumb body from the bough of the tree…. ”

Then Frank declares that Minnesota abolished its death penalty in 1911 and recounts quoting Martin Luther on orchards. “Even if I knew that tomorrow the world would go to pieces, I would still plant my apple tree.” The quotation elicits an emphatic response from the uncle, who by now appears to have swallowed his food. “That’s because,” he retorts, “that motherfucker never lived in motherfucking Minnesota.” (Frank 159)

This kind of warped syllogism recurs at breakneck pace in The Mad Feast. “Endnotes for the Sheboygan Bratwurst” are untied to any text and unconnected to each other. Examples: “Because this is a small town, the meth lab, by definition, is close to Walgreen’s” and “The Sheboygan brat as indifference toward equality.” (Frank 170, 171) The conceit is a good one, inviting the reader to ponder the content of the crazed phantom text.

Frank finds “Fata Morgana in the loosemeat sandwich,” which seems to be an eccentric burger something like the controversial chopped cheese that originated in the bodegas of the Bronx. He does ascribe the pasty to Cornwall but only by inference in the first instance. Another uncle (an avuncular trope recurs in The Mad Feast ), a miner, “has a bumper sticker that says FUCK CORNWALL THIS IS MICHIGAN.” The sticker has a sweeping significance and provides Frank with the opportunity to (sort of) describe a pasty and mine:

“If my uncle doesn’t have this bumper sticker, then he has black lung, and if he doesn’t have black lung, then he’s depressed due to lack of light, and if he’s not depressed due to a lack of light, he can call this only soul-sickness, can only lament the ways in which we’re not jacketed in pastry dough brushed with egg yolk, a crust that will protect us from birds who scream from the dark, from the lack of air that, in the beginning, seemed to exhilarate.” (Frank 187)

The upper Peninsula pasty, as Frank properly notes “when compared to the Cornish variety, contained larger chunks of vegetable, a higher ration of vegetable to meat, encased in a thinner crust.” (Frank 189)

Rhode Island chowder, the superior clear version of the New England staple, offers Frank an opportunity for an extended riff on transparency itself (“even clarity is confusing: we can’t tell which is the shit, and which the flower”) and the cataract (another uncle calls his “the Foreskin of the Clam”) interspersed with thoughts on Cassiopeia, the vain queen from Greek mythology, Cassiopeia jellyfish (nearly clear) and the wrath of Poseidon. (Frank 74-76)

Down in Louisiana, Franks finds “sad autoerotica” in crawfish etouffee, noting that the lips of Louis XIV on his deathbed “were slick with spittle, most historians can agree.” The Sun King has significance to Frank not only in the naming of Louisiana but also because the monarch “took his orgasms without oxygen.” (Frank 34) Frank later divulges the information that “[i]f desperate, the pelican, the state bird, will prey on seagulls and ducklings, holding them underwater, drowning them, before eating them headfirst.” Sometimes “they will open their bills and drink rainwater” too. (Frank 33, 34, 33-34)

Frank cites The Relativity of Deviance on autoerotic asphyxiation, “the first documented treatment used, in the seventeenth century, for erectile dysfunction;” witnesses to executions saw “persistent ‘death erections’” and “engorged labia.” (Frank 35) Next he proceeds to list a number of historical figures who accidentally died by practicing the procedure before noting that “[w]hen the female crawfish releases her urine, it drives the males into such a frenzy that, depending, it can be interpreted equally as an invitation to sex or to battle.” (Frank 35-36, 37) All this adds up in its way, but not in any mathematically recognizable manner.

In something of a surprise, The Mad Feast includes more than fifty recipes, many of them authentic and some of them appealing. Each chapter stands alone; a good bathroom book.