Another neglected outlier: Victor Gordon & The English Cookbook.

1. A lost resource.

In 1985 an oddity of the sort we celebrate at britishfoodinamerica appeared but then vanished in no time with no trace. Victor Gordon, the unlikely and eccentric author of The English Cookbook , “attended a one-day cookery course at St Omer Barracks, Aldershot during his national service” following the Second World War, an era when the food endured by British conscripts may have been the most abominable in the history of the army other, that is, than the disgusting rations endured in the trenches of the First World War. Gordon also did, his publicist notes, act as “one of Raymond Postgate’s principal lieutenants on the Good Food Guide .” ( English Cookbook flyleaf) Eating, however, is neither synonymous with cooking nor a qualification to write a cookbook.

2. An intriguing author.

In addition to his culinary avocation, Gordon held a number of day jobs, as a screenwriter for various food-related goods, all of them prominent fixtures in the British kitchen; Agas, the stoves without calibration or controls of any kind beloved by old money and neuves alike; Bovril; Guinness; Quaker Oats. Later he would move on if not up to edit “an international magazine devoted to boron chemistry” by which he appears to have referred to his tenure as “an industrial editor with the mining company Borax.” ( English Cookbook flyleaf; Prawnography flyleaf; Telegraph ) Gordon had a sense of humor.

Gordon found time to write a novel, Mrs. Rushworth a sort of sequel to Mansfield Park. It is pretty good, because he

“felt free to breach the narrow confines of Jane Austen’s world. There, though illicit passion, bastardy, seduction and desertion may be reported, they must occur offstage. Gordon had no such inhibitions.” ( Telegraph )

He was, it would seem, in a certain way the Wallace Stevens of cookbook authors, stuck in a workaday occupation but capable of literate lyricism.

3. Warning signs.

The English Cookbook does not start well. At its time nouvelle cuisine and cuisine minceur were attempting, like the revolutionary and then Napoleonic hordes at the close of the long eighteenth century, to make all Europe French. Gordon understandably became alarmed for the survival of British foodways, but rather than waiting out the enemy to wither from its own hubris like Kutuzov and the pyromaniacs of Moscow, Gordon decided, or so he claimed, to adapt antagonistic French doctrine to British conditions.

“We miss,” he argues, “a great deal through static loyalty to a stage-coach cuisine. French cooking has advanced creatively for 200 years, with each generation refining, re-assessing, refreshing the body gastronomic.” ( English Cookbook ) Ironically enough, it is French technique today that most appraisers consider static, while three decades after publication of The English Cookbook British foodways stand among the most innovative in the world, but not by aping French models. Gordon did not anticipate the development.

“The best nouveaux cuisiniers,” he insists, “are superb, creative, reforming cooks…. If the renewal of English cooking owes something to Messieurs Troisgros, Guerard, Bocuse et al, so much the better.” ( English Cookbook 11)

“We have” in England, he complained,

“a yeoman cuisine for a nation of car-drivers. The sturdy, fattening fare which was ideal for our ploughing, fighting, hunting, fathers has followed us to flats and semis. Fuel for physical toil, inner warmth against falling snows and rising damp, our famous dishes have been rendered anachronistic by labour-saving machines, central heating and the slimmers’ ethos.”

While Gordon thought traditional English “combinations of taste and texture are often inspired,” he found them “overweighted by the past, encrusted by offices they no longer need to perform.” He therefore advocated “a lighter, truer-tasting, more tempting cookery based largely on familiar ingredients…. ”

An example of the food advocated by Gordon is a ghastly “kedgeree without rice,” which turns out to be nothing but smoked haddock, butter and eggs. ( English Cookbook 285) This kind of thing demonstrates the inherent silliness of such an approach, for without rice (or cilantro, a pinch of curry and a drip or two of cream in our kitchen) this concoction is not kedgeree at all.

Too stodgy for modern life?

Traditional English dishes according to Gordon not only are stodgy (there is that rice); they also have suffered at the hands of both diners and cooks. “Spoiling perfectly good food by underrating or overcooking it is, of course, another obsolete practice still widespread in our kitchens.” (Gordon 4)

One English classic he did not find underrated was steak and kidney pudding, “the top ancient monument of the English kitchen--a glorious, anachronistic way of fending off the north-east wind. We no longer need such filling fare,” which, he thinks, is a good thing.

At its best steak and kidney pudding is but a “challenge;” at its usual worst an ungainly “compromise” of inferior ingredients, “an arranged marriage of different elements that meet for the first time on one’s plate.” In his estimation, “steak, kidneys and suet crust all take different times to cook, and this leads, far too often, to impenetrable steak, sodden crust or kidneys the texture of squash balls.” ( English Cookbook )

4. Rupert Croft-Cooke gets it right again.

All this is unaccountable to anyone who has eaten a good steak and kidney pudding, even a prepared one from Marks & Spencer or, better, Waitrose. As his lyrical description of the dish attests, Rupert Croft-Cooke for one knew better than Gordon. Croft-Cooke considered steak and kidney pudding “one of our few contributions to the haute cuisine of the world.” (Croft-Cooke 92) Why?

“In it the flavour is imprisoned by the suet pastry for the four or five hours during which it is steamed, giving to the resulting gravy and meat a richness of taste and consistency obtainable in no other way…. The whole point of the pudding is the long hours in which the meat slowly softens and blends with the herbs and spices, which must be used lightly, so strongly does everything sealed inside the thick blanket of white suet pastry keep its flavour.” (Croft-Cooke 92-93)

Or not quite white; “There is,” Croft-Cooke confides,

“a trick procedure here which I learned to follow many years ago, and which has stood me in good stead. Mix into the paste a very little black treacle (an invaluable thing to keep in stock in any case). This will give it when cooked that slightly golden colour and the suggestion of a taste of rum for which the steak-and-kidney puddings of a Fleet street pub were once famous.” (Croft-Cooke 93)

5. I can’t define it but I know it when I see it, and rely on something like the Pirate Code.

Gordon struggles to describe the English culinary tradition. “It is easier,” he thinks, “to sense Englishness than to define exactly what makes a dish English.” ( English Cookbook 4) He therefore imposes a set of “Rules & Regulations” or “Disciplines for Preserving--but Developing and Enhancing--Englishness in the Kitchen.”

These guidelines are not, Gordon explains, “inflexible rules” and “are invariably subjective, but they have been very carefully considered.” They include the use predominantly of “foodstuffs from (or readily producible in) the British Isles;” the use only of “exotic materials” that “have been continuously imported and widely used for around 100 years;” the rejection of “most outlandish, trendy or ‘new’ foodstuffs;” the avoidance of “ethnic” “processes and combinations;” the use of fresh, unprocessed ingredients; the reduction in the amount fat, flour, salt and sugar found in traditional recipes, but the use of “animal fats for meat and game cookery;” and improving “the status of vegetables” while continuing to give pride of place to “fish, meat, or game.” ( English Cookbook 287)

Following these rules would create “a cuisine of restricted range but very definite character as compared to the cosmopolitan approach…. Though simple and traditional, the techniques employed incorporate modern ideas in order to bring out natural tastes and textures.” ( English Cookbook 10)

Gordon prefigures the current controversy over cultural appropriation and articulates his opposition to ethnic borrowing in a most politically incorrect way. According to him,

“the new English cookery must be unashamedly racist as, for instance, the genuine Tamil, Nepalese, Korean or Caribbean cuisines we all now enjoy. Racial integration is a social imperative, but culinary apartheid enriches and intensifies the standard of life.” ( English Cookbook 6)

Inflammatory language aside, his point is not a bad one.

Other, however, than the rejection of rice and suet pastry, what can all this mean? Gordon does not require his reader to guess. Instead, he has compiled indices of “Traditional Foods,” “Naturalised Exotics,” “Borderlines (Use with caution, restraint and some reluctance),” “Stores and Proprietary Foods,” and an “Index Ciborum Prohibitorum: Not to be used in new English cookery.” ( English Cookbook 287-94)

6. Slings and arrows of a critic without principle.

For this last, and for using the term ‘racist,’ Christopher Driver has excoriated Gordon with neither mercy nor integrity in The New York Review of Books. “Repression,” of a kind Driver claims Wellington imposed on his cooks, “albeit of a more studied kind, has now returned to our food culture with the index ciborum prohibitum [sic] which Victor Gordon prints in his ‘unashamedly racist’ English Cookbook. ” In a rebuke to Postgate and his Good Food Guide as well as Gordon, Driver adds that the “French gentry have many faults, but at least they do not employ opinionated bumblers to instruct their cooks or criticise their restaurants.” (Driver)

This degree of his distortion is worthy of Donald Trump. In fact Gordon “was a man of progressive leanings both in his journalism and friendships.” ( Telegraph ) Not only did he explicitly decry racism as it is commonly considered (“integration is a social imperative”), but in fact he held all cuisines in high regard and had no intention of prohibiting anybody from eating anything.

In The English Cookbook , Gordon considers his prohibited ingredients inappropriate only if the cook wants to cook English food. They are fine, he believes, “for foreign and eclectic cooking,” which he has no desire to impede let alone proscribe. ( English Cookbook 5) A single example of his toleration appears appended to one of his recipes. “A puree of garlic would represent a trespass into foreign territory and [he] cannot possibly recommend it in a book such as this, except to say that it would be delicious.” ( English Cookbook 239)

Nor is Driver’s scholarly judgment so good as he would have his reader believe. Wellington was after all a duke, and Postgate would not have considered himself gentry, so the unfair reference should have been to French aristocrats.

The indices themselves require context. When The English Cookbook appeared, the British food revival had not gathered much force, and the legacy of rationing coupled with the proselytizing of Elizabeth David, Claudia Roden and others had left most British people with a better understanding of French and Mediterranean technique than of their own foodways. Gordon sought to reacquaint them with ingredients, and combinations of ingredients, that once had proliferated in British kitchens but outside a few stubborn redoubts in the shires had faded away.

7. Back to the food.

Fortunately, Gordon’s embrace of French tactical and caloric minimalism turns out to be little more than a feint. He considers animal fats fine for more than meat and game. Things like “beef dripping, pork lard, butter or bacon fat are often better than polyunsaturated vegetable oil, let alone soft margarine, for English-tasting food.” ( English Cookbook 6) Many of his dishes are sound, including an oxtail brawn bound with the gelatin of the meat. Gordon is no bumbler.

His page from The English Cookbook covering “The Roast” indicates that he is not really willing to throw les rosbiffs under the proverbial bus. His advice remains state of the art. Bones or a chicken carcass, “onion, garlic, a little water” sacrificed on the floor of the roasting pan will “help the eventual gravy.” Overheat the oven to start, moderate the temperature after ten minutes, baste from time to time with the emergent fat, some beer, cider or wine. Fatty meats and birds require a rack; roast beef should be rare, lamb pink, pork a bit more done.

“An important discovery of recent years,” Gordon understands,

“is that roast meat benefits by being rested…. This allows the juices which have been driven to the centre by the onslaught of heat from the outside, to steep back, redistribute themselves, and so make the cooking more even, the outside less dry.” ( English Cookbook 153)

Roasting for Gordon remains central to the English canon after all.

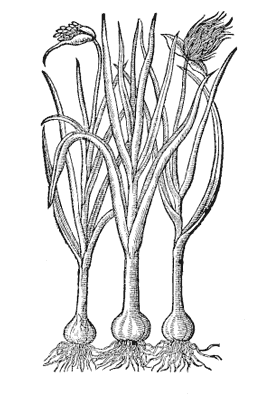

Elsewhere the indices and prohibitions in The English Cookbook may not be perfect but they do make sense. Fresh anchovy and sardine; forbidden, because they do not swim near British waters and historically were unavailable fresh. Canned anchovies and sardines are, however, permissible ingredients because the trading nation has imported them for centuries. Anchovy essence is welcome as well because it has flavored all manner of savory foods in Britain for ages, and British cooks traditionally reached for the condiment with more frequency than those of any other country.

Gordon might have allowed his new English cook the use of salt cod (prohibited) because it was long a staple of the laboring classes, as it was all over Europe, except that unlike the Portuguese and Italians they never acquired a taste for it. The trade in Parmesan predates the sixteenth century (Pepys famously buried a wheel behind his house to safeguard it from the Great Fire of London), so Parmesan alone among foreign cheeses finds a place in Gordon’s new English larder.

Gordon’s other distinctions share that logic. Fresh chilies or ginger, and “garam masala (and genuine Indian spice mixtures/pickles)” make no appearance in foundational foodways in Britain, so he excludes them, but the British invented curry pastes and powder so they make the grade if “Anglicised.” ( English Cookbook 294, 293, 292)

It would be difficult to argue against exclusion of most of the items that appear in the Index Ciborum Prohibitorum, ranging from avocado, bamboo shoots, kumquats and lychees to octopus, andouille and chorizo. Frog is the old English pejorative for Frenchman for a good reason, and sauerkraut never found favor either, even at sea in the age of fighting sail despite the efforts of the Royal Navy Victualling Board due to its long life in the barrel and antiscorbutic attributes. As the great naval historian N.A.M. Rodger has wryly observed of the sailors’ lack of enthusiasm for it, “an Englishman may be permitted to observe that an aversion to pickled cabbage is not necessarily the mark of unreasoning conservatism.” (Rodger 86)

Other items on the blacklist along with those fresh species of fish were just not available in the British Isles; “Japanese and Chinese condiments,” “sambals and south-east Asian condiments.” ( English Cookbook 294)

Passages of The English Cookbook read like dogma, but in actuality Gordon in practice appears both practical and flexible. The food police sneer at bottled sauces, but he finds it “silly,” for example, “never to use Worcestershire Sauce (if liked) or to attempt a home-made version.” Jars of chutney, pickled onions and pickled walnuts, Tabasco and treacle he admires, and he is right. We might, however, draw a line against the stock cubes.

Unrestricted imports include Madeira, Sherry and Port; rum; oranges and lemons (the bells of St. Clement’s) lime juice and, of course, tea. The spice trade is ancient and the British have made cayenne, cloves, powdered ginger, mace and nutmeg theirs for centuries.

8. The assembly of approved elements.

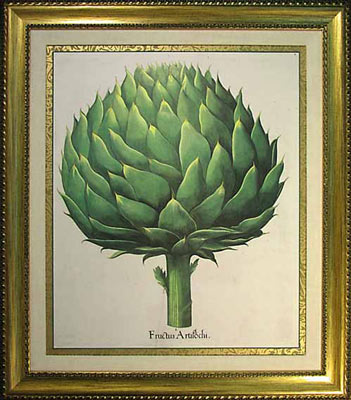

The recipes arising from all the pros and cons in The English Cookbook simultaneously display a sensitivity to tradition and some refreshing originality. Gordon likes to exploit ineffably English elements--bay, citrus, chutney, gin, marmalade, porter, tea, treacle, pickled walnuts--to emphasize the insular nature of the food he highlights. Two different sauces based on porter illustrate the approach. Both incorporate sour, spicy and sweet elements, a good formula for pairing with ham. One adds butter, bay, marmalade, treacle and pickled walnuts to the dark beer. The other fries onions in butter and deglazes them with vinegar before adding chutney, pepper and Tabasco along with the bay, marmalade and porter. Gordon makes “mulled artichokes” in a similar manner. [172-73, 209]

For “mulling” with porter.

Treacle also appears in venison braised with ale, bacon, bay, onion, tangerine, vinegar and cullis, [189] a throwback to the seventeenth and eighteenth century when its use was widespread. Cullis is essentially strong, defatted and highly flavored stock fortified following reduction. Gordon uses a number of them, and uses cullis in a lot of his recipes.

The first among equals starts with “compatible meat, carcasses, giblets, as available;” optional additions include “onions, carrots or other stock vegetables,” as we might expect. Once the meat stock has been reduced, he fortifies it with cider or sherry, mushrooms, tomato and vinegar. ( English Cookbook 26) As with the porter sauces, an interplay of sweet and sour, this time a subtle one, lurks within the recipe.

Gordon bases other forms of cullis variously on artichokes; celeriac and parsley; mushrooms, onion and parsnip; parsnip and watercress; spinach; tomato; watercress (spiked with lemon juice); other vegetables even including turnip; and various fruits.

Recipes incorporating cullis include a number of broths, liver with both English and smoked bacon, a porter sauce for steak, the braised venison, an inventive watercress terrine and others.

Gordon highlights barley, perhaps the most characteristically British of grains, as “a splendid and very historical alternative to rice, potatoes or pasta.” He is right about its “pleasantly ‘real’ taste and most distinctive texture…. ” In typically endearing style, he reassures readers that although “it contains masses of fibre, vitamins, minerals and protein, it is awfully good for you,” but “is by no means aggressive in its healthiness.” ( English Cooking 216) He has a cold barley salad, barley fried with bacon and onions, a roast duck and barley dish among others. None of them lacks appeal.

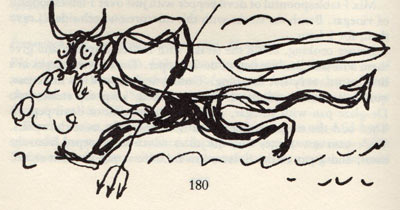

9. A detour to “the city and proud seat of Lucifer, high capital of Hell.” ( English Cookbook 181)

A British enthusiasm for devils erupted in the eighteenth century but had diminished by the end of the twentieth. That is a shame, as Gordon understands, for reasons both culinary and ethical:

“We seem to have cast the devil more effectively from our kitchens than, say, our bedrooms. It is possible that welcoming him back to the former would help expel him from the latter, since good dinners make for good marriages.”

“What,” Gordon asks, “is devilling?” It is uniquely British, if not for its piquancy then in the way the piquancy is produced. In contrast to chili borne curries loaded with a dozen or so “tropical spices,” devilling depends on “mustard, red pepper and melted butter. It may also be supported by anchovy, vinegar, black pepper, chutney and cream.” “Devils,” in contrast to curries, “produce clean and simple tastes, however hot and mustardy.”

Gordon draws the distinction between curry and devil for a single purpose; “the devil-eater can appreciate good wine, whereas the curry-eater cannot. The curry-eater has too much on his palate (and in his nostrils) to cope with another equally complex, taste experience.” ( English Cookbook 175) It is no coincidence” in Gordon’s mind “that devils were invented by--and for--a claret-besotted (sic) age.” ( English Cookbook 176)

The English Cookbook has recipes for devil butter, devil pepper and devil sauce, along with seven composed dishes, including “Pandemonium,” which he describes as “a very hot hotpot, fiery enough for the common run of demons.” A superstitious eighteenth century Scot would find its base appropriately porcine, with belly, ham, kidney and liver seasoned with various species of heat including chili and horseradish, cider, garlic, vinegar and Worcestershire. ( English Cookbook ) Worth selling your soul, if not necessarily for eating with an expensive Bordeaux. Try a cheap Chilean Carmenere instead and go to town, if not necessarily to Pandemonium.

10. Nontraditional condiments made from traditional things.

The use of cullis and devilling go back centuries in Britain, but the most rigorous research will not reveal reference to either ‘gustos’ or ‘zests’ because they are manifestations of Gordon’s imagination. “The gusto,” he explains, “is a cooked relish served hot or warm, while zests are composed of cold ingredients: both should be thick as jam.”

They “derive,” he adds, “from the fresh chutneys of Indian cooking and are particularly good with deep-fried food such as fish and chips.” ( English Cooking 237) That is fair enough in terms of Gordon’s guidelines: India has influenced British foodways for a lot longer than his hundred year cutoff in terms of authenticity.

The “sibling sauces” share a “forceful astringency,” and on that count also work with lots of things, including British-style hard cheeses, cold meats and charcuterie, other than deep fried foods. Watercress gusto is a puree of the greens, butter, egg yolk, lemon juice and dry mustard; among others are gustos based on anchovy and lemons themselves. Zests have foundations variously of cayenne, horseradish, onion or tomato. These fresh combinations are easy to assemble and extremely appealing.

11. An amiable prophet ignored.

All this should indicate that Gordon, despite his faux flirtation with French fashion, exhibited a lot of imagination while revering the traditions of the British kitchen. He also is a lot of fun, from his wry asides to the horrible puns and other silly names he applies to many recipes ranging from “abreast of the thyme” (chicken medallions flavored with gin and the herb) and blackerel (mackerel marinated in pickled walnut vinegar and served with a sauce including Guinness, treacle and Worcestershire) to “lame duck--When a duck has gone to pieces, that is when it is jointed, it can be helped by beer, treacle and prunes… ” ( English Cookbook 131; ellipses in original) His may have been a lost cause, but it prefigured the revival of British foodways even if it failed to spur the project along, and The English Cookbook is a literate joy loaded with accessible, refreshing recipes.

Sources:

Anon., “Victor Gordon,” The Telegraph (8 July 2012)

Christopher Driver, “Lamb’s Tails,” The New York Review of Books , Vol. 8 No. 11 (11 June 1986)

Victor Gordon, The English Cookbook (London 1985) Prawnography: A Candid Guide to the Greater Enjoyment of Prawns and Shrimps; with 150 Recipes (London 1989)

N.A.M. Rodger, The Wooden World: An Anatomy of the Georgian Navy (Annapolis 1988)