In (admittedly predictable) praise of public houses, their food & their habitués.

1. A century of last rites.

Back in 1989, Lesley Blanch celebrated the food of English public houses and lamented its decline. It is no small irony that while the food in public houses today may be of a higher order than in expensive formal restaurants, the public house itself lies under threat.

The Tory government of David Cameron not only racked up the disasters culminating in exit from the European Union via his forlorn attempt to marginalize party rivals. The Tories also tax beer at a rate in extreme excess of the levies on spirits and wine. Meanwhile demographic and cultural changes in the central cities of Britain have contributed to the decline in custom. The 67,800 public houses operating in the United Kingdom during 1992 had declined to 51,900 by 2014. (Langfitt)

Wandsworth in South London has been hit hard. Young’s, the iconic brewer, has sold its storied Ram Brewery; its flagship public house stands shuttered and forsaken, and Young’s now brews its beer virtually through a competitor. Developers clamor to destroy the Ram complex and replace it with something at titanic scale because the London real estate bubble has ballooned in the borough, and expensive apartments can generate a big, fast return on the site of any demolished public house.

Not dead yet…

And yet the demise of the public house has been imminent for nearly a century. In 1928, The New York Times reported that the number of them in London had declined by 24 percent since 1904. ( Times ) Hope therefore abides.

In The Local , Maurice Gorham noted during 1938 that nearly four thousand public houses traded in London, although that same year T.E.B. Clarke placed the number at precisely 5,361. ( Back to the Local 9; Clarke 162) While concerned about the threat to their traditional character from “rebuilding,” or renovation, Gorham evinced no concern about their survival. Eleven years later he had become alarmed. At that point Gorham feared his earlier optimism may have been misplaced because, he thought, “the pub-goer’s map of London was shrinking steadily long before the bombing began.”

Just as bad, or maybe worse, was the attitude of the big brewers that then owned the predominance of public houses in London:

“If you find a really modest pub, old-fashioned, unaffected, small, where you are given a welcome and can quickly get served, you might almost be sure that it is slated for demolition, though it may have been reprieved by the war.” ( Back to the Local 9)

“Progress, reconstruction, town-planning, war,” he lamented, “all have one thing in common: the pubs go down before them like poppies under the scythe.” The war had destroyed as well as preserved public houses. It “of course made terrible inroads; the Luftwaffe worked faster than the brewers and the Bench.” ( Back to the Local 90, 93)

And yet despite his fears, Gorham did note that postwar London “still ha[d] most of its 4,000 pubs” but he lamented that they, or most of them anyway, no longer served their signature sturdy and delightful dishes. ( Back to the Local 1, 62) “It is impossible,” he reminisced in 1949,

“to avoid a touch of nostalgia when it comes to food. Before the war it could be claimed that London pubs provided as good food of its kind as you could get in England…. Even as late as the time of the flying-bombs, there was a steak pie at the Rose of Normandy that I cannot forget.”

Gorham remembered “for one sad moment” steak and kidney pudding, smoked salmon, Welsh rabbit and “the Saloon Bar lunch at the Peacock in Maiden Lane (joint and two veg., but the best of English meat and English cooking with all the gravy).” ( Back to the Local 62) All of it vanished under the burden of rationing.

2. In the end there is comfort food.

Blanch was a less likely champion of public house food than Gorham, a flamboyant flaneur who extolled the exotic food she had encountered, or claimed to have encountered (Blanch liked to lie) all over the world, for the very most part outside the British Isles, in the company of celebrity, power and wealth. Late in life however, exiled in France, she confessed her culinary sins.

Pining for a good old pub.

“Grand food,” she had concluded at the age of eighty-five, “is not always good, nor is good food necessarily grand, while grub, so-called, the sausage and mash, jellied eel, shepherd’s pie or pork pie the plenty [sic] as once found in pubs, remains to me, at any rate, hors category--simply delicious.” ( Wilder Shores 85) Blanch also liked toad in the hole, and boiled corned beef with cabbage, Irish stew and all manner of suet puddings, both savory and sweet, which, she thought, “have nice names, and nice faces too…. ” ( Wilder Shores 86, 19)

Blanch wrote two cookbooks during a prolific and eccentric career, and in her typically perverse way never published any recipe for the dishes just described as her favorites.

The food in the public house, and the kinds of foods cooked in public houses more generally, had indeed declined when Blanch looked back, but during the intervening years has enjoyed a revolutionary revival that should not be confused with the very different rise of the gastropub.

3. A wizard of Oz.

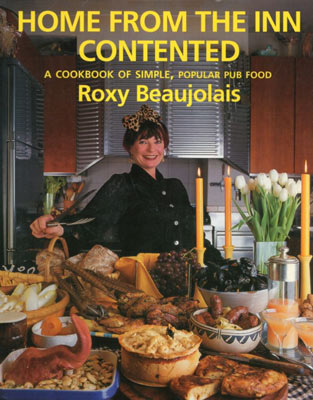

Another early adherent to traditional tavern food in London is Roxy Beaujolais. No less a luminary than Simon Hopkinson considers Beaujolais “such a natural cook that her recipes… will inspire all those who like to cook, more importantly, eat--and not even have to contemplate a coulis. ” (Beaujolais flyleaf)

According to Bruce Anderson, a High Tory provocateur at The Spectator , her immigration to England in 1961 was momentous.

“Australia was stricken by a cultural catastrophe. The damage to national morale has reverberated down the decades. It has contributed to the implosion of Australian cricket and the loss of the ashes, now irrevocable. The disaster occurred when the only two intellectuals in the convict settlements both bought one-way tickets to London.

Forty years on, Clive James is marginally better known. But from the outset, Roxy Beaujolais (nee Jean Hoffmann: New South Wales meets New Orleans) has been part of the va et vient.” (Anderson)

This of course is intended for fun, in the offhand offensive manner that considers the United States culturally stunted due to ‘premature independence.’ It is hardly contrarian of Anderson to admire James, arguably the most celebrated middlebrow public intellectual in Britain, but the celebration of Beaujolais is more original if widely enough shared among a certain demimonde. Her character and acculturation, even if ‘colonial,’ have appealed to intellectuals as well as luvvies and roues.

Anderson admires the Beaujolais pedigree and so do we. “For a time,” he explains, “she ran the front of the house at Ronnie Scott’s,” the legendary jazz dive on Frith Street in Soho. (Anderson) She has cooked for Isaiah Berlin and Stephen Spender among other luminaries at the Cranium Club.

Like Blanch, who favored flowing caftans, leopard print and extravagant clothing in general, Beaujolais cuts a flamboyant figure. Anderson describes her as “the girl who puts the ‘bon’ in embonpoint,” with “Chernobyl-pink hair colour” and suspects that cross-dressing Barry Humphries “is in charge of the make-up department.” (Anderson)

Now Beaujolais runs a clutch of public houses in London, and her outsize personality has rendered them unique. She always has cared about the food at her boozers: Anderson considers it “both hearty and thoughtful.” In 1996 Beaujolais published Home From the Inn Contented , a collection of dishes she likes to cook, and likes her cooks to prepare. The book percolates with her personality, the recipes simple, the results fine.

She is cost conscious, because she does not believe eating in a public house should require a fortune, and understands that beer and booze are the primary reason many customers, like the late Jeffrey Bernard, frequent her inns. Beaujolais has described him without a trace of exaggeration as “London’s most famous drinker.” (Beaujolais 10)

4. A prince of our disorder.

Bernard did not last long, but given his proclivities it is remarkable how long he did last. After enduring illness after illness--Bernard wrote around the age of fifty that his “body seems more and more addicted to the Middlesex Hospital”--he drank himself to death aged 65 in 1997. (Bernard 184) Before then Bernard had cut a considerable swath through a narrow stripe of Soho, primarily at the Coach and Horses, sometimes at the French House but also other public houses, including, as Beaujolais notes, one of hers, always in the company of accomplished rogues.

Jeffrey Bernard in a typical pose.

Despite his infirmities both genetic and self-inflicted, Bernard managed to write the regular “Low Life” column at The Spectator for over fourteen years while also contributing to other periodicals, most notably racing articles for Sporting Life , always from the perspective of the loser.

He thought his devotion to what he called “this farce of the low life” had been predetermined, first at an early age by his mother’s “cocktail parties for musicians, actors and actresses and stage people of all sorts:” Bernard “didn’t have to be more than twelve to see that they were getting a little more fun out of life than the Latin master at [his] prep school or the local grocer in Holland Park.” (Bernard 14, 13-14)

As he further recounts,

“I used to think that only theatrical people and the working classes got drunk and that racing was strictly for the upper classes and villains. The prospects were sheer heaven and I couldn’t wait to grow up.”

That was “the first act” of the farce. The second was the discovery of sex, at first of course autoerotricism, which Bernard “simply thought was a unique discovery” that he generously introduced to his “incredibly innocent prep school… feeling like Marco Polo returning to Europe with the new inventions of gunpowder and paper--and soon the entire school was rocked to its foundations both metaphorically and physically.” Then after he found a US Army sex education handbook “in some nearby woods” and “kissed a girl for the first time… you might say the rot set in.” (Bernard 14)

After prep school his mother sent Bernard to “a ghastly naval college called Pangbourne” where he “discovered the Turf” and “the demon drink.” Inevitably he was, to his immense relief, expelled, and at the age of fourteen chose Soho his “base of operations.” “It was,” he recounts, “instant magic for me, a sort of Disneyland for low-lifers.” (Bernard 14, 15, 16) His stint in national service was abrupt (he went AWOL but escaped censure) and Bernard never really left, not for long anyway, the set of this third act.

Bernard is good on the reasons for the attraction of his chosen theme park:

“One of the things I loathed most about school, the army and regular employment was the feeling that I was missing something and that in the pubs, clubs, cafes, dives and racehorse bars there was some sort of magic in progress that I wasn’t able to conjure with. How must a bank clerk feel when he sees the clock moving towards opening time or the first race?” (Bernard 108)

Anyone with an ounce of imagination has labored against, or gravitated to, the same enticing addictions.

Much like Elizabeth David he was, as Keith Waterhouse understood, “a short sprint man” whose best work came in under six hundred words: “Within that limit the miniaturist produced some gems.” He mined only the quotidian. “Out of the raw materials of a blank and uneventful day he could spin a ‘suicide note in weekly instalments’,” as Jonathan Meades, a formidable writer in his own rather more substantial right described the “Low Life” essays. Waterhouse considered Bernard’s best “funny, mordant, observant, evocative and haunting within a paragraph.” (Waterhouse)

The comparison to David is not so far fetched as it first appears. Bernard admired her writing, which could be as observant and acerbic as his own. He or David in person could electrify a room with intelligence, humor and charm. Like her he was by turns beguiling and incorrigible, even loathsome at times. “He could be boorish and dour, and was often unpardonably rude to those not quite big enough to take it. He would accept drinks from strangers and then tell them to piss off. He was something of a sycophant, cultivating the company of the famous and having his photograph taken with them in the manner of the Kray brothers.” (Waterhouse)

Both authors suffered ill health too early in life, Bernard from debilitating diabetes, pancreatitis and an array of other ailments, while a stroke at the age of fifty deprived David of both the ability to taste and her previously insatiable sexual appetites.

David relied on a sister for support during the latter half of her life, keeping the sibling a virtual slave and prisoner in the house they shared, while by the onset of middle age Bernard “had to rely on the kindness of strangers, he had long before exhausted the supply of kindness from his friends.” (Molloy) Other than the brief marriages, “Bernard always lived in one room--at someone else’s house,” where its paying occupant invariably “washed, ironed and cleared up for him.” Most of these benefactors were women. (Howse)

In their younger years, both Bernard and David seemed to possess the uncanny ability to seduce anyone they chose and also to immiserate their conquests. Graham Lord, literary editor of the Sunday Express , novelist and biographer of Bernard and many others, quipped of him: “He had a lot of wives, four of them his own.” (Waterhouse) Bernard himself described Susan Ashley as his “fourth, last and most angry wife,” who, he admits, “sensibly left me…. ” (Bernard 111, 191)

None of his women could compete with the booze or all those Soho rogues, who included Francis Bacon, Brendan Behan, Lucien Freud, John Hurt, Augustus John, Louis MacNiece, John Minton, Lester Piggot, Dylan Thomas and some more colorful characters. Bernard would banter with Ironfoot Jack; Handbag Johnny, who stole the bags for resale at Berwick street market; Sid the Swimmer, a bookie who got the name through constant struggle to keep his head above water. ( Desert Island Discs )

Bernard would become emaciated in middle age, not out of drunken disinterest in food but from failure to control his diabetes. He would lose a leg to the disease. Before then, Bernard noted a change in his reading habits.

“The literature on my bookshelves is gathering dust. There are only two things I read now, quite obsessionally too, and they are travel brochures and cookery books. Byron has been ousted by Elizabeth David, and the Sporting Life has been replaced by guides to the Greek Islands, Istanbul and India.” (Bernard 85)

That same week at the Coach and Horses, as Bernard indulged himself a reverie involving “the fizz of frying prawns, the dying hiss of a lobster and the rattle of a cocktail shaker” along with “the soothing and distant screams of German and Swedish tourists drowning in the foaming undertow” on faraway Barbados, the landlord of the Coach and Horses had upended the vision with an offer of supper. “‘Are you going to eat?’ he snarls. ‘We’ve got steak pie, chicken and mushroom pie, savoury mince and toad in the hole. Hurry up. Someone wants your fucking table.’” (Bernard 86) Ah London.

Elsewhere Bernard also mentions returning from France to the “steak pie and two veg in the Coach,” after musing that his “‘desert island’ meal, apart from a bible-and-Shakespeare sandwich, would be that old French standby of steak, pommes frites, salad, cheese and claret.” (Bernard 70) Pondering the same question a few weeks later he was not so sure.

“What came to mind the other day was desert-island food and it’s a tricky business choosing twenty-one meals assuming you’re going to eat breakfast, lunch and dinner every day. At first, what sprang to mind was cordon bleu, haute cuisine, provencale and all that sort of stuff…. But this excludes some of the great dishes of the world that have gone unrecorded by fatty Carrier and the great Elizabeth David.”

Bacon Butty

Among the unrecorded delights are standbys of the public house, although Bernard does lament “the ever declining standards of British pub food” during the 1970s and 80s. “Consider,” he demands, “the bacon sandwich washed down by a pot of Lyons Orange Label tea sipped from a bone china cup (mugs are for cocoa only).” Bernard sensibly prefers “bacon in the white sandwich loaf bread that’s supposed to be so bad for you--wholemeal bread detracts from the bacon flavor--” as it detracts from the flavor of just about anything other than smoked salmon, “and there should be just a hint of brown sauce.” (Bernard 138) The bacon of course must be the lean, unsmoked British variety, and if there were an effective hangover remedy this in the precise incarnation he describes would be it.

Along with Blanch, Bernard celebrates shepherd’s pie in addition to “the Beethoven’s Fifth of food, bangers and mash,” especially if the sausages come from Paxton & Whitfield and the potatoes are “whipped and not just pulped,” with a dose of egg yolk and cream. “Another gastronomic must would have to be the weekly injection of fish and chips,” although he finds English chips “too fat and soft,” and reminiscent of “fried cotton wool.” (Bernard 139)

Bernard likes bubble and squeak (“the prince of leftovers”), considers kedgeree essential and likes all manner of game. During his appearance on Desert Island Discs , Bernard’s chosen luxury was “a high powered hunting rifle and lots of ammunition” to fulfill three requirements. One was the acquisition of game for food, another to shoot “Man Friday” if he indulged in bad jokes and the other to blow his own brains out if he became ill. ( Desert Island Discs )

Bangers from here.

5. Back to the wizard.

The self-effacing Beaujolais does not harbor any delusion or ambition about joining a society of sublime chefs:

“My own very mildly creative occupation, cooking in pubs, is completely about dealing with the familiar. So much so that it’s main danger isn’t some trendy change for change’s sake, it’s overpredictability. I dice with banality.” (Beaujolais 6)

Her aim therefore is to “show how the ordinary can be made beguiling.” The watchwords: “Refined simplicity without perfectionism.” (Beaujolais 12) She therefore is more than

“prepared to admit that ultra-fresh free range eggs are strongly advisable for sunny side ups or perfect truffled scrambled eggs, but to the person withstanding the heat in the kitchen it’s usually more relevant to know that for glazing a pie a stale ordinary egg may do. Cooks have a right to be quite good enough whenever perfectionism becomes an obstacle.” (Beaujolais 12; emphasis in original)

Her kitchens stock commercial mayonnaise because it can be “absolutely good enough” and she admits “unashamedly” to “uphold the virtues of those sovereign bottled preparations, Tabasco, Worcestershire sauce and Maggi seasoning,” and sometimes resorts to frozen oysters and processed garlic. (Beaujolais 12, 13)

The workaday style in the kitchen and on the page is unfashionably refreshing. It also lies within

the tradition of public house food. “Making these terrible compromises,” she muses, “could explain why I cook in pubs instead of the Dorchester. Except they aren’t compromises, you know; they are form following function.” (Beaujolais 13)

By no means limited in scope to the archipelago, Home From The Inn does include lots of British dishes suitable for the kitchen of a public or private house. Classics include pie; raised Milton Mowbray pork, steak and kidney, chicken, leek and ham, shepherd’s, and cottage, others too. Oxtail stew dosed with bay, cloves and orange is more traditional than it may sound to the uninitiated, while “Cider with Pork” is the timeless mainstay of the west country. “Young people (also some drunks),” Beaujolais maintains, “love cider.” (Beaujolais 35)

Her cold poached pork loin is simple and foolproof. The kitchens of Beaujolais houses produce Blanch and Bernard favorites too; bangers and mash, bubble and squeak, toad in the hole and two good versions of kedgeree, one of them her father Freddie’s which, she cheerfully admits, is “utterly inauthentic” in its use of canned tuna instead of the traditional smoked haddock. “Kedgeree 2,” the traditional one, “would suit a bunch of hoorays after topping a fox, Kedgeree 1 the engineroom crew of a minesweeper (where… Freddie first mastered his dish).” (Beaujolais 91)

The Beaujolais idiom more generally should appeal to all spectra of society and so should she. Hers is the sensibility after all, one she shares with Bernard, that inscribed my copy of Home From the Inn with

“for Blake--

ah Liberty.

I shall see you at the Home for the Bewildered.

-Roxy.”

6. The (sort of) twenty-first century reprise.

Never someone to pass on the main chance, or the chance just to make a pound, Gordon Ramsay employed his co-author to exploit the public house genre in 2009. Gordon Ramsay’s Great British Pub Food includes lots of big color shots of the bad boy and recipes that may or may not share a connection to the public house. One ‘recipe,’ for oysters, tells the eager reader to shuck them and serve them with a mignonette of shallot, wine vinegar and pepper. No thanks for that manifestation of Ramsay’s perpetual effort to extend and exploit his brand.

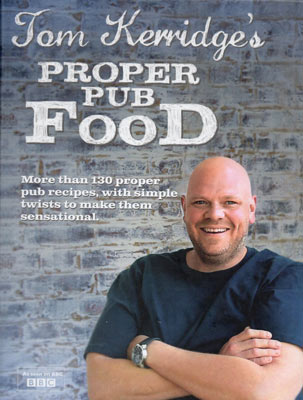

In 2013, however, Tom Kerridge followed the Beaujolais lead, with a good cookbook if neither an inscription nor her subversive streak. Like Ramsay, Kerridge stretches the definition of public house food, but also offers some appealing and original versions of traditional dishes in Proper Pub Food. Most of Blanch and Bernard’s favorites go missing, but at least Kerridge offers his reader corned beef (but for bagels); fish and chips; pork pie; Gorham’s beloved salmon, in Kerridge’s case cured with gin; venison and other roast meat; an array of suet puddings.

If Ramsay amounts to a belligerent didact, Kerridge wants to come across as an affable enthusiast. The book, tied to a BBC television series of the same name, suffers for that with its surfeit of exclamation marks, sometimes rendered in triplicate, and in its devotion to the peculiar British vogue for archaic usage, from the ‘proper’ of its title to terms including “Hello you!,” “dead easy” and the serial resort to “give it a go.”

Like Beoujolais, Kerridge considers economy crucial to his cooking. “For me,” he explains, “really great pub food should be accessible to everyone without having to compromise on standards. It should offer value for money--notice I haven’t said that necessarily always means cheap, but it certainly means value for what you’re eating.” (Kerridge 6) Also in common with Beaujolais, Kerridge hopes to give some spark to the otherwise quotidian,

“to take ordinary, even everyday dishes and make them extraordinary…. It’s all about the food being approachable and available to everybody. Not to mention good, honest dishes with the flavor and taste that’s the result of taking a little more time, care and attention to prepare them.” (Kerridge 7)

His third point of convergence with Beaujolais; Kerridge includes dishes from around the world in his book because they proliferate in public houses, although his devotion to the British culinary tradition is the more pronounced.

Consider something as simple as a solution of treacle and water for curing beef. It is an evocation of eighteenth and nineteenth century English technique. For example, an early nineteenth century North Country recipe boils beef in beer with treacle; Elisabeth Ayrton found it in a household manuscript to include in her magnificent Cookery of England back in 1975. “The tradition in the household,” according to Mrs. Ayrton’s source,

“was that the dish had been prepared in the past by their parsimonious ancestors for the hay-making supper for tenants, because part of an old ox which had been kept to work all winter could be used, since the beer helped to tenderize the meat.”

No matter the mean motive: “The tenants liked the taste of the beer and considered the dish a grand one.” (Ayrton 53)

While Kerridge is by no means parsimonious in taking his treacle to cure filet of beef instead of tough old ox, the result is equally appealing, and “[y]ou can,” as Kerridge notes in ungrammatical prose, “use the treacle cure mix for beef, venison or chicken, and then grill them on a barbecue.” (Kerridge 163) He might have added pork chops to the list.

Kerridge has a simple and sublime way with ham. Two of his recipes poach thick slices in butter and water for service with fried capers and other things. One of them cooks broccoli stalks (he prefers “to the florets, as they have a better flavor and such a good texture’) in the liquid first, which further flavors the ham. (Kerridge 80) The buttery “glaze” fulfills a third function as the only other element of parsley sauce for the ham. Brassica, ham and parsley; a British culinary triumvirate with an original twist.

Mushrooms on toast, a homely paragon, are most welcome in any incarnation, and Kerridge’s creature represents a good one. The sourdough base and truffle oil, used here with rare good effect, may not be British but do no harm. Taking a page from Prudhomme, he deepens the flavor of the dish by combining four elements of the allium family to sharpen the loamy fungus too. Tout va bien. That applies as well on balance to Proper Pub Food and, perhaps, the prospects for the public house and its food.

Notes:

-Although it is not altogether clear, Bernard’s reference to a bible and Shakespeare sandwich apparently does not describe a food. Participants on Desert Island Discs are allotted those titles (Bernard wants none of them) and allowed to choose an additional book of their own.

-Roxy Beaujolais is landlord of The Bountiful Cow, Seven Stars, and Three Greyhounds in central London.

Sources :

Bruce Anderson, “Drink: The star of the Stars,” The Spectator (27 August 2011)

Anon., “London ‘Pubs’ Have Dropped 24 Per Cent. Since 1904,” The New York Times (26 February 1928)

Elisabeth Ayrton, The Cookery of England (London 1975)

Roxie Beaujolais, Home from the Inn Contented: A Cookbook of Simple, Popular Pub Food (London 1996)

Leslie Blanch, From Wilder Shores: The Tables of My Travels (London 1989)

T.E.B. Clarke, What’s Yours? (London 1938)

Maurice Gorham, The Local (London 1938)

Back to the Local (1949)

David Hall, Worktown (London 2015)

Christopher Howse, “Obituary: Jeffrey Bernard,” The Independent (5 September 1997)

Tom Kerridge’s Proper Pub Food (Bath 2013)

Frank Langfitt, “London Borough Raises Pints--And Legal Protections--To U.K.’s Fading Pubs,” NPR (13 September 2016)

Sue Lawley (interviewer), “Jeffrey Bernard,” Desert Island Discs (15 March 1991) (BBC podcast accessed 17 October 2016)

Mike Molloy, “The last ever Jeffrey Bernard anecdote,” The Guardian (15 June 2005)

Gordon Ramsay & Mark Sargeant, Gordon Ramsay’s Great British Pub Food (London 2009)

Keith Waterhouse, “Last Call for Jeffrey Bernard,” The Telegraph (13 September 1997)