A tale of two, Irish, cities.

1. Trouble no more?

It cannot be the worst of times in a long time for the competing Irish capitals. Uncertainty over the status of the border between the republic and the north threatens the sectarian settlement brokered twenty years ago, but not much, at least not at this point.

Meanwhile the republic has reimagined its educational system, with exemplary results, by wresting it from the catholic church and its deplorable Christian brothers. The constitutional ban on abortion even has been overturned in a landslide referendum result. Dublin also has spent its EU money wisely and recovered with aplomb from the slump of 2008.

The Troubles no longer trouble Belfast, at least for now, and if sectarian suspicion and even bigotry do remain, things are so much better in terms of tolerance, in particular amongst the young, that it is hard to imagine citizens of the city tolerating a return to paramilitary violence whatever their demographic or tribe. Ironically the political picture hardly reflects the truce. The DUP and Sinn Fein now dominate elections, and their mutual hostility is so extreme that Northern Ireland has not formed a government at Stormont for a year now.

The electoral support for Sinn Fein is particularly puzzling. If The Economist may be believed, with the caveat that it cannot always be believed, nearly nobody, northern or southern, wants a united Ireland. Citing a poll from 2015, the magazine reports that only 11% of people in Northern Ireland and 31% in the republic favor unification. (Economist) But then Ireland never has made much sense to outsiders.

2. Virtual unreality.

While it pales in importance compared to politics and peace, a certain cultural dissonance also confronts the discerning observer. The biggest tourist attractions in each city rely on the very nearly fictitious. The most visited site on the entire island is Guinness Storehouse, the ghastly Disneyfied cartoonish virtual interactive advertisement concocted by Diageo that brews no beer. In the north, the similarly digitized Titanic Museum at the mouth of the Lagan celebrates film as much as ship, while tourists flock to the soundstage for Game of Thrones.

3. The real seagoing deal.

Go past the soundstage along the river toward the Irish Sea and visit HMS Caroline instead. A light cruiser laid down in 1914, she is the sole survivor of Jutland, now impeccably restored to its 1916 condition but for the obtrusive auditorium amidships that replaced the torpedo battery and ship’s boats when Caroline was converted to a training vessel.

The ship occupies an interesting niche in the history of naval architecture. She was built for speed and inadvertently for comfort. The speed required high freeboard for heavy seas, and Caroline’s prominent prow is an unmistakable feature of her class. The turbines and boilers required a lot of space so Caroline has an incongruously large if narrow hull given her relatively light original armament of four six inch guns, four four inch guns and those torpedoes. As commissioned of course she had no radar or other electronics, no ammunition hoists, primitive central fire control and radio equipment; neither of them required much room.

As a result Caroline is a remarkably roomy ship for both officers and crew without the cramped quarters that characterize vessels as big as Washington Treaty battleships. Roomy but probably not comfortable given that narrow beam; Caroline would have rolled with abandon in a brisk seaway. But except for the canted hull and ports, the officers’ mess looks more like the elegant dining room of a country house or gentlemen’s club--replete with gramophone--than the functional cramped compartment of a fighting machine. And notwithstanding the mythic lore of rancid meat and weevilly bread, both officers and crew ate well enough; the officers very well indeed, as attested by the big stove and ovens in the galley, housed on the main deck in the Royal Navy tradition.

4. Vanished Ireland.

Back on shore things have been lost, especially in Dublin. Clerys has closed and O’Connell Street more generally remains a disgraced shell of former glory, although to be fair the trash and litter there seems less prominent than they appeared a year ago. La Mere Zhou carved its last chop a long time ago, while the Bailey and Davy Byrne’s, the Joycean public houses facing off across Duke Street, have devolved into pricey tourist traps. Shiny resuscitated Bewley’s is not quite the same shorn of its shabby chic, and the new incarnation does not even serve its signature barm back. Still, the place has at least returned from the grave in all its Arts & Crafts comfort.

In Belfast, the great cranes of Harland & Wolff still stand at the mouth of the Lagan, the stationary and forlorn legacy of an industrial heritage both heroic and bigoted. The once bustling enclave of Shaftesbury Square has devolved into squalor, Paul Rankin’s incomparable Roscoff restaurant lost long ago.

No Guinness anywhere is pumped by hand anymore; the evocative wooden spatulas swiped across a pint to level the head are as ghostly as Leopold Bloom, and any number of bartenders hastily pour an improper pint. The stout share of beer sales declines apace, and the dismal cabins of Aer Lingus have ditched it in favor of bland warm Heineken.

MIA even on Aer Lingus

5. Feeble foodways.

For our purposes, however, this is no time for elegy or indulgence in nostalgia. In culinary terms nobody in either Dublin or Belfast has cause to complain. Good things grace both cities to the astonishing extent that each one is a genuine destination for its foodways alone.That was never much the case. During the eighteenth century heyday of the patriot Ascendancy, British visitors to Irish estates and Dublin townhouses marveled at the lavish hospitality of their hosts. They found the amount of consumption urged upon them quite literally insane, but their letters and journal entries generally decline to extol the quality of either the food (drink was something equally plentiful but altogether different; grandees spent recklessly to buy the best). In terms of style, extant records indicate that other than an increased but not pronounced prevalence of potato in various guises, the dishes cooked and eaten in upperclass Ireland were for the most part indistinguishable from those in Britain. The notorious nineteenth century in terms of Irish cooking is so widely known that recapitulation would amount to repetition.

From independence in 1922 until the dawn of this twenty-first century, most of the Irish seldom ate in restaurants. At home they aspired to little other than a reassuring trinity of meat, potato and vegetable simply served separately or stewed. ‘Famine foods’ like forage, fish--especially shellfish--and game found no favor despite their quality and abundance.

6. Two different towns.

All has changed, and nothing terrible tarnishes the culinary transformation other than the dearth of decent craft beer relative to Britain and more especially America. Farmers raise heritage pigs and more generally produce meat of unsurpassed quality; the produce has improved beyond reasonable expectation; and chefs select a lot of Irish ingredients for their kitchens. As, however, it historically has been the case, Irish and British foodways merge more than diverge.

The two cities retain their distinctive characters, and the cultural contrast remains acute. Passengers wait in ordered and convivial queues for the train from Belfast to Dublin, while Dubliners bound for Belfast assault it in a riotous scrum.

7. On Belfast.

In 1919, E. M. Forster wrote an otherwise sour short essay in which he asserted that

“Belfast, as all men of affairs know, stands no nonsense and lies at the head of Belfast Lough.”

Those were the only things approaching kind that he could bear to say about the city. He did find its bookstores “instructive,” but not in any favorable way. “They are not only small,” he found, but incredibly provincial,” trafficking only in the dully didactic self-help manuals of Samuel Smiles or in pornography “bound up in red and gold and usually tied up in string.”

Nothing like that now is the case. Belfast stands a lot of nonsense now. What other city supports a bookshop named for Flann O’Brien but not by name? Any city would like to have Keats and Chapman. And what other city could mount the Northern Ireland film festival?

Notwithstanding its legacy of violence, an old saw holds that Belfast is the friendlier city and the saw cuts clean. Although the permafrost of Dublin has softened, even has melted away in places and especially amongst the young, the city can be cold, even unkind to visitors, and Dubliners tend to remain unloved beyond the Pale. In a contrast ironic given its history of sectarian conflict, everybody in Ireland appears convinced that the people of Belfast stand among the most gregarious, welcoming and hospitable urban inhabitants in the western world. That conviction is not misplaced.

A rainy Saturday, and it always rains in Belfast, at the Ulster Museum; jesters on stilts, jugglers, clusters of children immersed in art workshops compete with the visitor’s attention for a path to the paintings and artifacts, and that is just the beginning, on the entrance stair and in the lobby. Crowds of families mash into elevators and strike up vertical talk, even with American outliers, in the seconds it take to ascend or descend.

The narrative in the Irish history galleries is more nuanced and less anachronistic than in the National Gallery or Museum of the republic, not really anachronistic at all in this corner of the north and an evocation of hope for a secular future.

St. George’s Market

8. On Belfast food.

We, however, run a journal concerned primarily with food, so our appraisal of Belfast turns there. Much but by no means all of what makes the city stand out in culinary terms is new. Sawer’s justifiably describes itself as “an Aladdin’s cave of culinary delights.” It has been an exemplary source of cheese, game, cooked and cured meats, fresh seafood, their own marmalades and preserves as well as lots more since 1897.

The impatient will, to their immense loss, want to avoid St. George’s Market, constructed in three stages between 1890 and 1896. No hard sell in the wonderful Victorian hall--much of Belfast is Victorian or Edwardian while in contrast to Dublin the eighteenth century is thin on the ground--but much genial banter from the stallholders offering samples of their considerable wit and wares. Transactions take time; craic is a component of the currency.

In a sense the market encapsulates the spirit of its contradictory city. As Kim Lenaghan, who has a culinary program on BBC Radio Ulster explains:

“This is a city where we like to talk and laugh; we don’t do things quietly and that includes food. The market gives us a chance to be who we really are.” (Deseine)

The many stalls selling seafood all display the freshest fish; clear eyes, scarlet gills and an absence of ‘fishy’ smell. Heritage pork and free range beef, famed Irish lamb, all from local farms, sell at fair prices. Produce too, and street food, and a hatter who refused to sell anything until the buyer has tried a range of sizes to ensure a suitable fit.

Lunch at the Ulster Reform Club, founded in 1885, features traditional Ulster dishes befitting a conservative institution devoted to preservation of the union with Britain. Not much deference is given outsiders in terms of nomenclature; the menu describes smoked salmon served with wheaten, which for the uninitiated is Ulster for brown soda bread; white bread, faris.

A bowl of sausages with champ (not translated either) and gravy is as simple as it sounds but also sublime. The sausages are made from smoked bacon and heritage pork, the champ a champion comfort food made with outstanding ingredients; potato, scallion, butter and milk topped with a fragile tracery of fried onion. In common with the most ambitious restaurants in Belfast, the club buys its meat from the celebrated Hannan’s just outside the city.

Also born in its present incarnation during 1885, the Crown Liquor Saloon flaunts hallucinatory tilework, stained glass, burnished wood and a row of the wonderful snugs that have been ripped from nearly all other Irish bars to make room for more drinkers and profit. It is, as its website boasts, “one of the mightiest Victorian Gin Palaces in the city,” if not the mightiest in the world. Here is a good description from visitbelfast.com:

“Where else would you find a burnished primrose yellow, red and gold ceiling, a floor laid in a myriad of mosaic tiles, brocaded walls, ubiquitous highly patterned times [sic], vigorous wood carving throughout, ornate mirris, wooden columns with Corinthian capitals and feather motifs in gold with painted and etched glass everywhere [?]

Vivid in amber and carmine painted shells, fairies, pineapples, fleurs-de-lis and clowns, incidentally the colourful decorative windows fronting the bar were originally intended to shield customers from inquisitive passers-by. The long Balmoral Red granite topped altar bar is divided by columns and faced with gaily coloured tiles and a heated foot rest.”

A decade past, the saloon served only two things, but it served very good ones; oysters on the half shell and Irish stew. The menu has expanded and the oysters are gone but fortunately the stew abides.

Esprit emanates from the world of Belfast food. Restaurants are nearly New Orleanian in their willingness to cooperate and collaborate. When the crowd subsides late in the evening at Edo (Latin: “I eat”), the line cooks in the open kitchen happily converse with curious diners. They source their beef from Hannan’s too, and bathe cheek in sous vide for a day before braising it for hours more. A treat. You are visiting Belfast? Where else will you eat? Oh, good choices all. The place with all the panties and bras waving from the ceiling? That’s Muriel’s, the former bordello. You will like it, and we did; good unorthodox spring rolls and, more traditional, a soothing chicken, ham and leek pie.

Muriel’s upstairs.

The fish pie at the boisterous Barking Dog out past the Gothic fantasy of Queen’s University is even better. Stocked with the freshest fish and served with a dariole of minted peas, this is sheer tradition lightened with aplomb. Go ahead and stir the peas into your pie after piercing the perfect crust. The dog is famed for its small dishes described as tapas. The preparations owe more to Asia and Ireland than Spain but no matter, the little plates more than justify their reputation. Badger your personable waiter enough and he will sell you one of the restaurant’s serving shirts.

A last note on Belfast: The Mourne Seafood Bar is yet another friendly place that might, however, give more training to its staff before setting them loose in the dining room. Our lovely Slovenian waitress eagerly responded to a request for dark rum with an offer of Guinness, but then the oysters from Carlingford justify their fame and the place knows how to cook a whole fish on the bone. Incidentally the price of wine just about everywhere is more than fair. No New York markups of over 100% in Belfast.

9. On Dublin food.

The Winding Stair, quayside north of the Metal (more commonly and less evocatively ‘ha’penny’) Bridge, once like so many bars an anchor of literary Dublin, held three floors of shelves laden with books used and new. All, or almost, all of that is gone, and for a change the loss entails a gain. A café and small bookshop remain on the ground floor along with the winding stair, but now it leads to a peerless restaurant. It shares a certain aesthetic with St. John in London but surpasses its British template in service, style and food. John Banville recounts dining there in Time Pieces, his evocative memoir of Dublin. (Banville 108) The author eats as well as he writes.

It is not possible to imagine better smoked haddock than the fish in the dish at the Winding Stair. It bears but the hint of sweet smoke, poached with precision to remain bright and light, not normally tones associated with smoked haddock. There is an irresistible slab of toast to soak up the milky broth. They do not push the dish but are pleased if you like it. Only after we made the enthusiastic point did our waitress shyly confide that it is their signature dish.

A younger, almost equally appealing Mr. Fox in Parnell Square is another incongruous outpost on the scruffy North Side. Its kitchen is more refined than the Winding Stair’s but not, quite, on par, which renders the food quite good indeed.

10. Back to the best bar.

Perhaps the best in its quirky way, however, we have reserved for last. As we wrote a year ago, no music, live or otherwise, no television, no gambling machines. No guest beers, no daily specials, no artisanal cocktails. No advertising nor slinky barmaids; no female staff at all.

If Guinness has fallen from favor in relative terms, traditional stout from the Liberties remains the standby. The place retains four of the last indoor gaslights in Ireland, its marble bartop, its snug (only one, but then every other public house in the republic seems to have torn theirs out), its sparing nod at visual art, the iron arms outside holding lanterns to beckon custom. This is Neary’s.

Always described as ‘Victorian,’ Neary’s is not quite so, the most austere and best of Dublin’s storied nineteenth century public houses. The atmosphere is all Arts and Crafts, more William Morris than George Gilbert Scott.

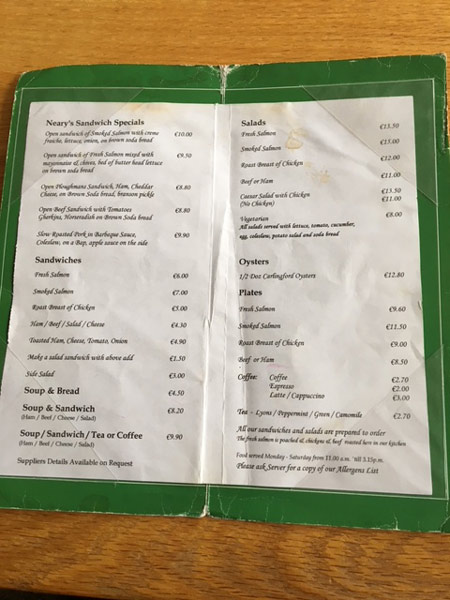

A Wadsworth treagle lifts food from its kitchen, extremely good food, from a short, alliterative selection of sandwiches, salad and soup--nothing more except, sometimes, seasonal oysters as pristine as any in Ireland--and only from 10:30 am until 2:45pm, but never on Sunday. If food were its only draw, Neary’s would be worth a trip from far away. The public house offers exemplary brown, white and, yes, soda bread; poaches its own salmon; roasts its own beef; and obtains its food from superior sources, including smoked salmon from the celebrated Wrights of Howth, where they have oak smoked and hand cut their fish since 1892.

Is it possible Neary’s has gotten better over the last year? It is, if only incrementally because the standard on Chatham Street is so high, and it has, because more of the peerless sandwiches now also arrive openfaced on soda bread.

Garrett and the rest of the wonderful staff are still there, among the ghosts of all the literary lions who drank there. Some still do; it is John Banville’s favorite of Dublin bars, “a civilized house” in contrast to McDaid’s, which, he is right again, can be most unfriendly. (Banville 101) Follow his lead: Go to Neary’s.

The Neary’s menu.

Note: For more on Neary’s, its literary lights, its treagle, food in Irish literature and more, see the Perkins article from bfia included in the sources.

Sources:

Anon., “Crown Liquor Saloon,” https://visitbelfast.com/eat-drink/partners/crown-liquor-saloon (accessed 15 April 2018)

Anon., “Northern Ireland: Past and future collide,” The Economist (31 March-6 April 2018)

John Banville, Time Pieces (London 2017)

Trish Deseine, “OFM Awards 2016 best market: St. George’s Market,” The Observer (16 December 2016)

Blake Perkins, “More than the dude abides, at least in Dublin if no longer in Bolton across the Irish Sea, being a meditation on Neary’s & Flann O’Brien with a digression on the first Bloomsday,” www.britishfoodinamerica.com No. 53 (Summer 2017)