A wonderful cookbook embedding a flawed premise: Jubilee and the antecedents of African American foodways.

Jubilee by Toni Tipton-Martin is the logical outgrowth of an earlier research project, The Jemima Code: Two Centuries of African American Cookbooks.. It is a groundbreaking book that appeared in 2015, a descriptive bibliography of published cookbooks written by black Americans from 1827 through 2011. The earlier publications represent a phenomenon resembling a miracle: Two of them appeared during the era of slavery in the United States, if in the abolitionist capital of Boston, and another pair before the end of the nineteenth century in the less likely locations of Paw Paw, Michigan, and San Francisco.

This last, unlike many of the other books in the Code, has been celebrated for some time. What Mrs. Fisher Knows about Southern Cooking, Soups, Pickles, Preserves, Etc. first appeared in 1881 and has been available in facsimile at least since 1995. An autodidact in the kitchen, Abby Fisher was illiterate but even so ran a successful pickle and preserve company with her husband. Notwithstanding the disadvantages attendant on being black, they won prizes at San Francisco competitions and the state fair in Sacramento.

Mrs. Fisher also operated a catering service and must have been a beloved figure among the bay area society ladies who populated her clientele. It was nine of them from both Oakland and San Francisco who transcribed the recipes for the book and published it through their Women’s Co-operative Printing Office. (Hess 75)

Another author who has enjoyed a revival of sorts, Pamela Strobel, who wrote as ‘Princess Pamela,’ also appears in the Code. Her bluff and whimsical Soul Food Cookbook had first appeared during 1969; the art publisher Rizzoli reissued a typically beautiful edition in 2017 with an introduction by the prolific and celebrated Lee brothers.

The cast and vintage of the Fisher and Strobel books contrast enough to encapsulate the broad range of the African American kitchen across space and time. Tipton-Martin chose to include Mrs. Fisher but not Princess Pamela in Jubilee, a conscious, and symbolic, decision.

Jubilee is by any measure a wonderful cookbook. Tipton-Martin is a gifted writer whose prose, free from jargon or the more contemporary linguistic abominations, serves her historical analysis and recipe selection equally well. The inclusion of historical recipes to accompany some of the meticulous ones that Tipton-Martin has created and tested for the modern kitchen is most welcome. Her seven variations on cornbread, including the two historical ones, alone would encourage anyone to buy the book.

The Tipton-Martin project, however, aims to serve a higher purpose, nothing less than the rehabilitation and celebration, as its title infers, of an accomplished African American culinary tradition, a tradition that thrived notwithstanding its denigration, not least through the perpetuation of demeaning stereotypes found even in the titles, as the name of The Jemima Code itself purposely reflects, of the published cookbooks themselves.

In the process of compiling The Jemima Code Tipton-Martin discerned “the framework of a distinct African American canon.” (Jubilee 14) “Through the embrace of classic techniques, formal training, global flavors, and local ingredients,” she asserts, “African American cooks… demonstrated habits that break the soul code, while inspiring pleasurable cooking with style.” (Jubilee 13)

She cites the redoubtable Arthur Schonberg, writing in the 1920s, who explained that “ ….the negro genius has adapted English, French, Spanish and Colonial receipts [Schonberg even got the historical term for the modern ‘recipe’ right] to express his own peculiar artistic prowess,” and herself adds the Caribbean archipelago, Brazil, Italy and, in common with Karen Hess, Africa above all as influences. (Jubilee 14, 15)

As the title Jemima code indicates, Tipton-Martin considers ‘code’ a term freighted with negative historical significance, even perhaps an inferential reference to the ‘slave codes’ of the antebellum south, Caribbean and South America. The reference to a soul code in Jubilee is telling, for among the stereotypes that Tipton-Martin decries is the caricature of all black cooking as soul food, a style she believes black people have been “pigeonholed in.” (Jubilee 9) She therefore has “tried to end dependency on the labels ‘Southern’ and ‘soul.’ The terms trouble her because of their association with “assumptions about” her

“ancestors’ contribution to mindlessly working the fields where the food was grown, stirring the pot where the food was cooked, and passively serving the food in the homes of the master class.” (Jubilee 13)

Her ambivalence, even misgiving, about the idiom may explain the absence of Princess Pamela’s Soul Food Cookbook along with nine of the fourteen other books from Jubilee that include Soul Food in the title. That deemphasis and those omissions skew the historical record, driven as they are by ideology more than culinary content or merit.

3. African American women of note.

Hess along with Tipton-Martin emphasizes the African inflection of black cooking in the United States. In her ‘Historical Notes’ to the 1995 edition of What Mrs. Fisher Knows, she writes of Mrs. Fisher that “she had clearly long been steeped in the best traditions of Southern cooking,” of the south itself that “African aromas were everywhere” and

“Southern cuisines were… transfigured by the genius, indeed the very presence, of the African women cooks in the kitchens of the wealthy slaveowners.

In addition, these women cooks had brought their ancestral ways with a number of products from Africa by way of the slave trade or elsewhere in the African Diaspora of the New World, such as the West Indies, such as okra, cowpeas, sorghum, and rice, all indigenous to Africa, as well as benne seed and eggplant, long cultivated there.” (Hess 75, 80, 79)

This line of argument turns out to be as awkward as the writing in which it is presented.

Six ingredients do not a singular or distinctive canon make while in fact Hess neither identifies any of those ancestral ways nor describes those ubiquitous African aromas. What then of the recipes from Mrs. Fisher, the particular collection Hess purports to address? Do they reveal an African influence?

4. What Mrs. Fisher knew.

Tipton-Martin describes or simply mentions seven recipes or categories of them in Jubilee. One of the recipes, “Ochra Gumbo,” is misnamed. Lacking roux, file, even the Louisiana trinity of celery, onion and bell pepper, the dish is a simple soup of chopped okra boiled in beef broth, simply seasoned with only salt and pepper, “[t]o be sent to table with dry boiled rice.” (Fisher 23) While okra originated in Africa, by the late nineteenth century people of any hue or ethnicity in the south had been cooking with it for some time. By analogy tomatoes originated in South America but that fact does not render Tuscan sugo de carne Peruvian, and anyway Mrs. Fisher’s soup uses neither African technique nor seasonings.

The other dishes from Mrs. Fisher that Tipton-Martin describes are not distinguished by anything either African or uniquely African American; biscuits, croquettes, gingerbread, waffles and “just six salad recipes” that, Jubilee claims, “reflected her Alabama roots.” (Jubilee 121) Each of them is composed only of chopped meat or seafood and celery simply dressed with a standard mayonnaise mistranscribed by the ladies of the Women’s Cooperative as “Sauce Milanaise.”

Nothing about these dishes is peculiar to any ethnicity, to Alabama or any other locale in the western world. None of them nor any of their ingredients, however, emerged from Africa. All the Fisher recipes from Jubilee appear in any number of British and American cookbooks from earlier eras, the croquettes also under the name of various cakes (crabcakes, salmon cakes and many others) or rissole.

5. Anomalies out of Africa and Indian country.

One of Mrs. Fisher’s dishes which, oddly, Tipton-Martin omits from Jubilee, does look like it likely originated with African American cooks in South Carolina. An early jambalaya, also mistranscribed by the bay area ladies, as “jumberlie,” and described as “A Creole Dish” is more a classic rendition of lowcountry perloo or pillau. It is not, however, the first use of a jambalaya variant in print, as Hess would have it. Three years before Mrs. Fisher, the church ladies from Mobile, Alabama, who complied the Gulf City Cookbook included a recipe, if rather eccentric and economical in its use of chicken feet and gizzards, spelled “Jam Bolaya.” (Perkins, “Antecedents, authenticity and adaptation”)

The jumberlie, it transpires, is an outlier. Very little else from What Mrs. Fisher Knew appears particularly Creole, African or African American.

Another outlier, this one her “Circuit Hash,” bears an obvious debt to the eastern native American tradition. (see Hess 84) The dish composed of butter beans, corn and tomatoes--the decidedly nontraditional addition of pork is listed as an option--likely is a mistranscription of succotash.

All this therefore raises the question what influenced the dishes that she describes. Both Hess and Tipton-Martin provide hints, about both their antecedents and the antecedents of African American foodways more generally.

6. An unheralded inheritance.

In her historical notes, Hess notes that “the overwhelming basic influence over the various Southern cuisines was English” but also discerns “strong streaks of French and occasional traces of other kitchens,” and could have added that those same streaks and traces had by then also influenced English cuisine itself, before making her unsupported assertion about the ubiquity of “African aromas.”

Throughout What Mrs. Fisher Knows the English stamp is so strong that if its author and place of publication were unknown, the likeliest conclusions would identify her as English and its location London except, possibly, for the dearth of herbs or spice other than cayenne and the stark simplicity of the recipes.

7. An English pathway; cayenne by any other name.

As for the cayenne, notwithstanding conventional wisdom its use in no way exiles a cook outside the English kitchen. “Cayenne pepper,” explains leading authority on all things capsicum Marisel Presilla, “also spelled ‘cayan,’ ‘chyan,’ and ‘kian’ was well established in English kitchens by about the middle of the eighteenth century.” She does not identify African or any other influence carrying cayenne to North America or to England for that matter. (Presilla 117; Perkins, “Authenticity and Appropriation” 41)

By 1817 the English were cultivating chilies themselves. In The Cook’s Oracle, his bestseller in North America as well as Great Britain, William Kitchiner recommends making cayenne, in England then a mixture of sundried chili and flour, from English peppers because “Indian cayenne is prepared in a very careless manner, and often looks as if the pods had lain until they were decayed.” (Kitchiner 182; Perkins, “Authenticity and Appropriation” 41)

Of the first forty three dishes from What Mrs. Fisher Knows, some forty are simple, unremarkable renditions straight from the Anglosphere, including chow chow and chutneys, a game sauce and ketchups. There are exceptions, but they are the kind typically found in a cookbook featuring English preparations and related ‘exotica.’ That strange ‘Ochra Gumbo’ is, perhaps, something of an outlier along with corn and tomato soup but the recipe called “Oyster Gumbo Soup” is for no such thing. Essentially an eccentric chicken and oyster stew with the addition of “one tablespoonful of gumbo,” it is unclear just what additive Mrs. Fisher had in mind because the etymology of the term gumbo itself is unclear. (Fisher 22)

The Angolan word for okra is “ngombo” while the Choctaw native to Louisiana called ground sassafras, or file, “kombo.” Either ingredient acts as a thickener, and based on the small amount specified Mrs. Fisher may refer to file, but then unlike okra the ingredient appears nowhere else in her cookbook. Either way the odd dish appears to be one of its few original creations. (Dean)

Elsewhere the game sauce is recognizably a Cumberland sauce based on plums rather than redcurrants, likely a preference rather than substitution because Mrs. Fisher uses currants in other recipes including the classic English jelly.

Otherwise there is little deviation from an early nineteenth century English norm. She boils a lot of puddings and uses suet in a lot of them according to the English manner. The suet is a particularly prominent marker. It is not a traditional item in the African kitchen and the French do not even have a term for the substance, which has permeated much of English pastry as well as pudding technique, sweet as well as savory, from the late seventeenth century on.

Mrs. Fisher roasts beef and cooks “Yorkshire Pudding To Be Eaten With Roast Beef.” The roasting method is, according to Hess, “exemplary.” “Follow her instructions to the letter if you would have properly roasted beef, rather than the grey, sodden stuff fobbed off as roast beef in our modern cookbooks.” (Hess 87)

Everything about the statement is preposterous. No modern cookbook advocates cooking grey sodden beef while Mrs. Fisher provides nearly no guidance at all. “A five-pound roast,” she says, “should cook in half an hour, a ten-pound one in one hour.” Because the recipe dates to 1881, the oven at issue had no thermostat so Mrs. Fisher cannot provide a roasting temperature. She could, however, have disclosed whether her beef is roasted on the bone or not and specified a cut or cuts. Hers is not a recipe useful to our times.

Others are in fact exemplary. The “Meat Dressing,” actually a hot, sweet and sour condiment made from carrots, cauliflower, cayenne of course, onion, black pepper, brown sugar and vinegar, is reminiscent of Dr. Kitchiner, who included a slew of these bottled sauces in his Oracle. (Fisher 39)

Two others in particular merit attention, one for spiced beef, the other for boiled turkey with oyster dressing. Mrs. Fisher does specify a cut, round, to spice. Her pickle for curing the beef emerges straight from the British and Irish canon. She rubs down the meat with the requisite salt and seasons it with generous doses of allspice, cayenne, clove and black pepper. Some recipes specify a dry cure, others a wet one. On this rare occasion Mrs. Fisher goes the relatively maximalist route by adding vinegar. After a weeklong cure the round goes into the pot with its accumulated juices and a small proportion of water to ‘boil,’ which cooks of the time understood as simmer for a dish like this, for a little over four hours. Mrs. Fisher is right: “The most delicious appetizer among meats.” Slice it paper thin. (Fisher 56)

The boiled turkey is one of the more complicated recipes in What Mrs. Fisher Knew on account of the dressing and an English white sauce. The stuffing too is of typical English pattern. It consists of the oysters, chopped ham and veal and crushed browned crackers (breadcrumbs would be better) seasoned with dry mustard. The turkey itself gets a “high seasoning” of cayenne along with the obligatory salt and pepper. The bird goes into a muslin bag, pudding style, to boil for about an hour. A sound formula that works with consistency, incomparably easier and more reliable than roasting a turkey, although the stuffing could use a binder of egg and suet.

The sauce (Mrs. Fisher uses the homely term gravy) starts with a thickener of amalgamated cold butter and flour, also seasoned with dry mustard, and boiling milk stirred “till it is as thick as honey.” A lost but noble dish that requires revival.

There are of course--this essentially is an English cookbook--exemplary desserts; a fruitcake, mince pies, plum pudding and all those other boiled puddings among them.

9. Incognito Englishry.

Sometimes Mrs. Fisher or her transcribers disguise English preparations in foreign garb, a practice also prevalent in Britain at the time. A chutney made from cucumber, chili, red onions, bell peppers, sugar and vinegar for example appears as “Napoleon Sauce.” Those disguises do not erase the English origin of the preparations.

As may be expected from her other enterprise, What Mrs. Fisher Knows is notably strong in the category of pickled and preserved goods. On that front Hess, hardly a culinary Anglophile, does trace the recipes more generally to their actual source:

“The English had long possessed an excellent preserving tradition, and it was retained in full glory in the South, to some extent because the procedures are highly labor intensive and the wealthy Southern slave owner had virtually unlimited staff in kitchen and garden.”

Hess emphasizes the English nature of the preservation formulae employed by southern cooks in general and Mrs. Fisher in particular. “The pickled mango recipes,” she explains,

“are not actually for mangoes, but continue the English tradition of substituting various fruits and vegetables for the stuffed pickled mango from India.” (Hess 89)

Necessity also played a prominent role in preserving the English preservation tradition in large parts of the American south because the hot climate could cause spoilage of fresh produce as well as fish or meat at an alarming rate.

11. Murmurs of modernity.

The style of Mrs. Fisher is not all retrograde. Her cookbook at times reflects the fluid nature of Anglo-American foodways toward the end of the nineteenth century. Her fish chowder is a good example of the phenomenon. Its traditional base of salt pork layered with fish, onion and crushed cracker is supplemented with potato and water, emergent ingredients like clams absent from earlier chowders. (Perkins, “An Enquiry into the Derivation of Chowder” 31-33, 47) Then again Mrs. Fisher may not have been so sure about the potato: After providing an amount and the instruction for slicing it she forgets to layer her potatoes into the chowder itself. (Fisher 60)

Mrs. Fisher also anticipates the, very, gradual reduction of reliance on sugar in the American kitchen, a trend that unhappily has begun to be reversed by the industrial food establishment in our own time. “Abby Fisher,” as Hess notes out of nowhere, “gives few sweet dishes, and those few are not very sweet.” (Hess 88)

12. On to the twenty-first, or is it the early nineteenth, century?

The terms ‘England,’ ‘Britain’ and their derivations do not appear as index entries in Jubilee and Tipton-Martin goes so far as to close The Jemima Code with a quotation from John Egerton that includes his opinion on the inadequacy of British food:

“‘Without the contribution of black cooks it [southern cuisine] might have been as boring and bland as British food,’ he declared boldly.” (brackets in original) (Jemima Code 235)

Despite his prolific scholarship on the subject of southern food, Egerton displays an anachronistic ignorance about traditional British cookery and therefore about the extent of their influence over the development of southern cuisines. A diligent dig into the text of Jubilee uncovers the explicit and implicit recognition that British foodways have exerted such an influence, perhaps the dominant influence, on the foods it describes.

13. Precepts and evidence for an extraordinary life.

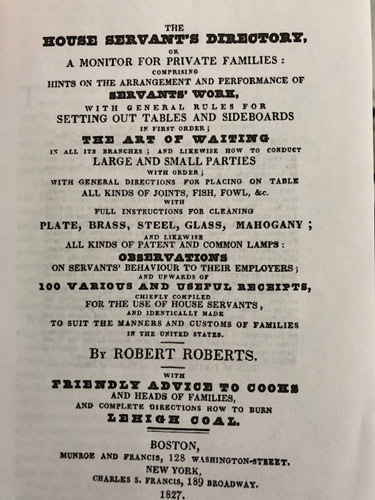

The Home Servant’s Directory is the earliest work Tipton-Martin describes in The Jemima Code. Its author, Robert Roberts, is a formidable figure and the trajectory of his life is fascinating. He was born in Charleston, South Carolina, sometime around 1777: It remains unclear whether his parents were free or enslaved, but by the time he had arrived in Boston during 1805, Roberts was fully literate and, based on the contents of his Directory, a gifted writer who had read widely.

Roberts apparently also had worked as a head butler because immediately upon arrival in the hub of the solar system he began managing the household of Nathan Appleton, a prominent financier. (MSU Libraries 1)

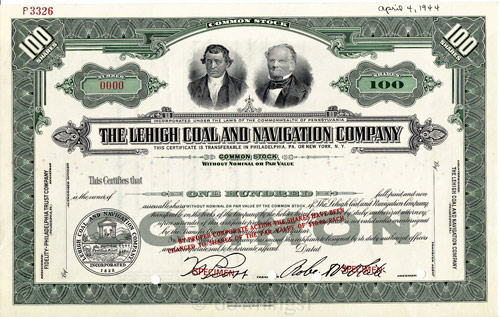

Given his occupation as a butler rather than cook, it should come as no surprise that the Directory is not really the cookbook she calls it but rather, as its full title demonstrates, a detailed manual of foodways more generally. In common with nearly every English language household manual of its time, and the genre was nearly as popular as the more specialized cookbook, that title is extremely long, extremely descriptive and extremely promotional:

“The HOUSE SERVANT’S DIRECTORY, or A MONITOR FOR PRIVATE FAMILIES comprising HINTS ON THE ARRANGEMENT AND PERFORMANCE OF SERVANTS’ WORK, with special rules for SETTING OUT TABLES AND SIDEBOARDS in first order; THE ART OF WAITING in all its branches; and likewise how to conduct LARGE AND SMALL PARTIES with order; with general directions for placing on table ALL KINDS OF JOINTS, FISH, FOWL, &c.

with full instructions for cleaning PLATE, BRASS, STEEL, GLASS, MAHOGANY ; and likewise ALL KINDS OF PATENT AND COMMON LAMPS ; OBSERVATIONS ON SERVANTS’ BEHAVIOUR TO THEIR EMPLOYERS ; and upwards of 100 VARIOUS AND USEFUL RECEIPTS, chiefly compiled FOR THE USE OF HOUSE SERVANTS, and identically made TO SUIT THE MANNERS AND CUSTOMS OF FAMILIES in the United States By ROBERT ROBERTS with FRIENDLY ADVICE TO COOKS AND HEADS OF FAMILIES and complete directions how to burn LEHIGH COAL.” (emphases, punctuation and spacing in original)

Last but not least, how to burn it.

The contents of the Directory contain nothing remotely African. They do, however, reflect a very different influence.

Roberts opens his chapter called “A Few Observations to Cooks, &c.” with a paragraph continuing the trope that he is addressing two readers, a Joseph and a David. Then, as the rest of the chapter he reproduces verbatim Dr. Kitchiner’s “Friendly Advice to Cooks and Servants” from The Cook’s Oracle other than his precepts for “marketing.” On that subject Roberts includes his own better and more detailed advice in a separate chapter. To his credit, Roberts in turn credits Dr. Kitchiner, an imposter who was not really a doctor, in full for his ‘Observations to Cooks.’ The attribution is no aberration. When Roberts borrows, in contrast to his many contemporaries who plagiarized with abandon, he cites his source.

Dr. Kitchiner is not the sole English influence on the Directory.

Roberts scatters some twenty three recipes through the book, twelve of them for drinks and mostly for lemonades, cider and beer but including “a beautiful flavoured punch;” no Noah Webster Americanisms for him. All of the beverages with the possible exception of spruce beer bear an unmistakable English ancestry. The punch is a classic British combination of brandy and rum sweetened with sugar, and flavored with the requisite citrus note, in its case lemon. (Roberts 88-89)

Roberts has a pair of noteworthy cold sauces. The salad dressing is a quintessentially English composition originating in the eighteenth century, relying as it does on sieved hardcooked egg yolks to thicken a compound made from the anchovy sauce beloved of English cooks since the seventeenth century, ‘made mustard,’ oil, vinegar and “one gill of milk or cream,” this last still an element of English salad creams. (Roberts 74-75)

The other, a mustard mixture, Roberts explicitly attributes to “M. B. of London.” It steeps horseradish in the stock left from cooking corned beef, strains it and uses the flavored stock to moisten mustard flour heavily seasoned with salt. A good formula, according to Roberts “absolutely the best I have ever met with, as it much surpasses any other, both in strength and flavour;” not an idle boast. But do not make too much at any given time; “you should never mix more than half your mustard pot full at once, as it is better when first mixed.” (Roberts 75)

Roberts writes with the same clarity and sense of purpose throughout the Directory, and seldom stoops to patronize his reader. He is good company.

14. Anglophilia in early national New England.

Roberts was writing at a time when cookbooks by British authors published in both British and American editions remained immensely popular in the United States, and that at least in part may explain his Anglocentricity. In addition, Federalist Boston and its environs constituted the most Anglophile region of the early national republic, and Roberts spent twenty two years as a head butler for Boston families.

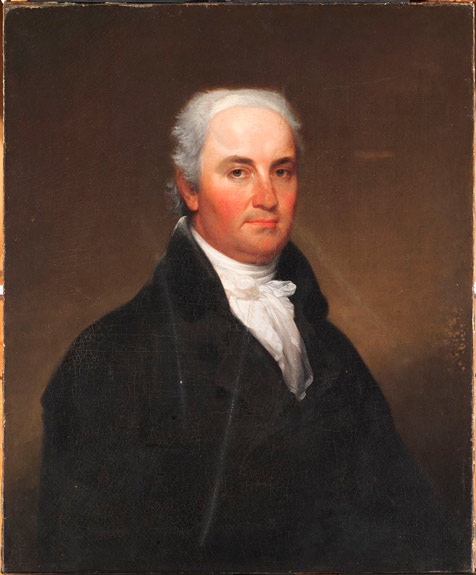

His most significant stint as a household manager came during the last two years of his service career. From 1825 until 1827, Roberts ran the country estate of Christopher Gore, a prominent Boston lawyer who had served in the Continental Artillery after graduating from Harvard, where he met and became lifelong friends with Rufus King and John Trumbull, who would paint portraits of the Gores. (Pinckney 14)

During the early years of his practice Gore made a fortune speculating in Revolutionary War debt, and invested the money wisely to increase his already considerable holdings. Subsequently he served under King as Commissioner of the United States at the Court of St. James after his friend had been appointed ambassador.

On his return to Massachusetts Gore served terms as governor, then senator from Massachusetts. He placed a premium on good relations between Great Britain and the United States, and as governor opposed the War of 1812. (MSU Libraries 2)

Trumbell’s Gore portrait.

He is among a largely forgotten hybrid species of statesman, the progressive Federalist. His interests ranged from architecture, landscaping, emerging technologies (he was one of the founding investors in the Lowell textile industry) and historical research to agricultural improvement. (Pinckney 92; SAH Archipedia) He “believed in the aristocratic tradition of the trusted man-servant as well as the American free enterprise system which made such luxury obtainable.” (MSU Libraries 2) Apparently Gore also believed in at least the relative equality of blacks and whites, women and men.

His relationship with Roberts appears to have been more as colleague than boss, a factor that may have helped lure Roberts away from his previous and longtime employer. Mutual respect and reciprocity of obligation between employer and employee represent precepts of Roberts’ Directory. One obligation of the employer entails providing his employees with an agreeable working environment. Once again Roberts relies on Kitchiner at length:

“A good dinner is one of the greatest enjoyments in human life; and as the practice of cookery is attended with so many discouraging difficulties, so many disgusting and disagreeable circumstances, and even dangers, we ought to have some regard for those who encounter them. To procure us pleasure, and reward their attention, by rendering their situation every way as comfortable and agreeable as we can.”

Kitchiner and therefore Roberts are unequivocal in considering conditions as crucial as compensation, especially for cooks:

“Mere money is a very inadequate compensation to a complete cook; he who has preached integrity to those in the kitchen may be permitted to recommend liberality to those in the parlour; they are indeed the sources of each other.”

Roberts insists that generosity invites integrity. Writing in his own words, he advises employers to “give those you are obliged to trust every inducement to be honest, and no temptation to play tricks.” (Roberts 123)

Roberts witnessed Gore’s will, and found enough time away from his duties at Gore Place to write the Directory, which appeared two weeks after Gore’s death. Gore himself wrote its introduction and may have helped finance the project and facilitate publication. A reflection of this rapport with Gore, Roberts includes in the Directory

“extraordinary recommendations on how relations between servants and masters should be conducted on open, honest terms to benefit both sides.” (MSU Libraries 2)

It was the first book written by an African-American to be published by a commercial entity in the United States. (Bachin 13) Roberts had aimed his directory at the narrow niche market of African American men interested in a career of service but it found a broader, unintended audience. According to a Michigan State scholar,

“its advice would serve an ever broader class of workers as domestic servants became scarce and the growing hotel and restaurant business required more and more knowledgeable staff who could elegantly host and feed large groups of people.” (MSU Libraries 2)

The Directory enjoyed four print runs ending in 1837, and Roberts had to have made money from his writing because he died one of the wealthiest African Americans in Boston, leaving an estate worth $7,541.99, or upwards of $232,000 in current value. (Cruickshank & Katz 39; Bixler Reber)

Either Gore was too congenial an act to follow or Roberts had tired of household management, because when Gore died Roberts become, of all things given his background, a stevedore. The vocational transition of a well-read esthete to a manual laborer demonstrates the difficulty, even in abolitionist Boston, African Americans encountered in finding the kind of work their qualifications ought to have made possible.

These later years of his long life were hardly empty: Roberts, who would not die until 1860, became active in the abolition movement, serving on numerous committees and continuing to write, for William Lloyd Garrison’s influential Liberator. (MSU Libraries 3)

15. A detour to Waltham.

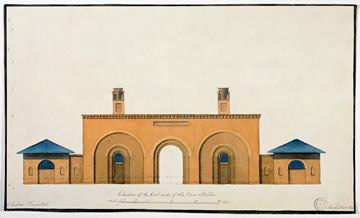

In an extraordinary decision for his time, Gore left the design of their Waltham retreat to his wife, Rebecca, the daughter of another prominent Bostonian. No other contemporary woman in America was entrusted with so significant an architectural task.

While her husband was serving as a diplomat with the fledgling Department of State, the couple spent a considerable amount of time in England and traveled extensively in Europe. Rebecca Gore adored the study of architecture and took her own version of the ordinarily male Grand Tour to seek out the famed structures of the day.

Perhaps on that basis, one scholar considers the house Gore designed retrograde and derivative. “Although built 21 years after independence,” Gauvin Alexander Bailey claims without elaboration, Gore Place “still adheres to metropolitan British styles.” (Bailey 33) He only can have taken the most cursory glance at her building.

That judgment also entails a certain irony, because the only record of any contact between Rebecca Gore and an architect in connection with the design of Gore Place was French, Jacque Guillame LeGrand, whom she had met in Paris. Some writers maintain that LeGrand collaborated with Gore on the design of Gore Place but the written record demonstrates something different. According to Christopher Gore’s biographer,

“ ….in London after six months on the Continent, Rebecca Gore sketched plans of the house she wanted to build in Waltham, and when she had finally achieved a satisfactory expression of her ideas, she sent the draft to Legrand. (Pinckney 85)

In correspondence with King, her husband writes:

“Mrs. G. has sent the plan of our intended house, with a wish that you should explain it to LeGrand, & request him to make a compleat & perfect plan according to our sketch.” (quoted at Bachin 4)

LeGrand himself

“was a celebrated architect but also a theorist, known more for his publications and designing large public buildings, than as a designer of houses.” (Cruickshank & Katz 85)

During the era when Gore Place was built, skilled builders throughout New England either relied on English pattern books or bore major responsibility for supplying the details to architectural plans, and Rebecca Gore, not LeGrand, was on the ground to instruct them, so it is more than reasonably certain that the house was built to her design. Whatever role LeGrand did play apparently was limited: The meticulous Gore account books include no entry for payment of a fee to Legrand or any other architect. (Pinckney 88)

It should not be surprising then that Gore Place, unlike for example the contemporary New York City Hall, bears no trace of the frillier Renaissance Revival style then favored in France, and its austere severity very nearly rules out any French influence.

From all this it appears that Rebecca Gore was responsible for the design of the house and LeGrand executed her plan as draftsman.

Christopher Gore’s confidence was justified: In Gore Place Rebecca Gore produced a masterpiece, perhaps the finest example of a Federal era country house in the United States. (see e.g.; Bachin 12)

In their encyclopedic if mistitled survey of Architecture and Town Planning in Colonial North America, James and Georgiana Kornwolf are unequivocal:

“The severe, linear cubicity of the Federal idiom can be seen at its purest in the ambitious Gore Place.” (Kornwolfs 1453)

More accurately a house from the Federal era but not quite a Federal style house; Gore Place is too imaginative for so confining a description. Not that Gore did not draw on architectural precedent; she did, but in doing so designed a building at once faithful to the Massachusetts idiom of Bulfinch and Asher Benjamin but also striking in its originality.

If, as the songwriters say, you are going to steal, then steal from the best. Bailey is right to the extent that some of Rebecca Gore’s influences do appear British, although obviously he has overlooked the Bostonian sources that stood quite literally beneath Gore’s nose: The couple also kept a house in Boston’s fashionable Bowdoin Square, long sadly lost to urban renewal, where they spent most winters.

The particular buildings that inspired Rebecca Gore must remain a matter of informed speculation, because no extant letter or other document refers to any of them. It is possible, however, to discern some likely sources. Gore Place sounds echoes of Lord Burlington’s pathbreaking Chiswick House of 1729, especially the syncopated Palladian windows of his rear façade and in her subtle gesture toward a central dome. Gore’s work however is more graceful, severe, even abstract: Unlike at Chiswick, no classical or Palladian orders, no pillar, base or capital adorn the house in Waltham.

A better architect than Burlington appears a stronger influence on both the exteriors and interiors of Gore Place. Sir John Soane was perhaps the most coherently imaginative architect of his time in the world. If his contemporary and rival Nash was all surface and theater, Soane’s was a style marked by the manipulation of spaces through playful erudition and adaptation, not necessarily stripped like Gore Place, although sometimes, but always idiosyncratic, always all his own. There is no mistaking a Soane building and in that sense his work is timeless.

His name nearly never merits association with an American building, but several scholars have speculated that his influence appears at Gore Place, although none of them identifies a particular Soane building. (see, e.g., Cruikshank & Katz 84) The shadow of his work, and in particular the celebrated stables he designed in Chelsea for Wren’s Royal Hospital, does appear to inform and enliven the house the Gores built.

So to the building itself. “The design featured an inter-play of geometrical shapes, including carefully laid out oval parlors…. ” and featured skylights; Soane is the unrivaled master of the skylight. (Cruikshank & Katz 84; Pinckney 86) These interiors, as Christopher Gore wrote to King, enjoyed “perfect freedom from ornamentation.” (quoted at Pinckney 87)

In terms of elevation, Gore Place is a symmetrical composition consisting of a Boston style bowfronted central block dominated by an elliptical one and a half story reception room. Narrower hyphens, or wings, flank the central block. Perpendicular pavilions, one for a music room, the other for the kitchen, rooms that logically should farthest from the rest of the house, close each hyphen.

“The overall effect,” G. E. Kidder Smith concludes, “is elegant,” although he finds “confusion” in an unusual feature of the central block. (Kidder Smith 146) Instead of a single entry, Gore Place features twinned entries, one into the front hall with its spectacular circling stair, the other into the butler’s pantry.

In reality no confusion mars the design, and maybe Mrs. Gore was making a subtle but pointed gesture with her unconventional entry plan, a gesture in line with Roberts’ advocacy of an agreeable environment. Nobody always need enter Gore Place out of sight to the rear, not, of course, the esteemed guests but neither the butler nor his staff either. Separate and equal entrances for all, but equal nonetheless.

Syncopation describes the planform of Gore Place in terms of sold and void. As the Kornwolfs add: “The seven-part composition of fifteen bays is more severe than Bulfinch’s work, scrupulously avoiding application of the orders.”

They also describe “its remarkable abstraction, for example, in the insertion of ordinary windows within an arched bay,” and although they did not notice the parallel, that arched abstraction arises straight from Soane’s Chelsea stables. (Kornwolfs 1453) Also in distinction from Bulfinch, Gore Place eschews the spindly verticality of voids that often characterizes Bulfinch buildings.

More severity; semicircular windows to the ‘ordinary’ windows within each recessed arch of the hyphens while recessed gestures of pilaster flank the windows fronting each pavilion. Throughout the house, oversized windows along with the skylights bathe the interiors with light. Gore place is magical.

18. High tech too, and a highly skilled COO.

Gore Place supported a sophisticated social swirl and guests included any number of luminaries, Lafayette, Light Horse Henry Lee, President Monroe and the immortal Daniel Webster among them. (Cruikshank & Katz 84; Kornwolfs 1454; Pinckney 141)) To manage this elaborate environment, Roberts supervised a staff of fourteen, with the power to hire and fire male employees. (Bachin 16) Given the demographics of Massachusetts at the time, Roberts therefore held a position of authority over white people in the Gore household, a good reflection both on his skills and on his employer.

Those skills cannot have been limited to managing a workforce, for Gore Place was a technological laboratory as well as architectural showpiece. The house featured central heating fired by anthracite, less smoky than the traditional ‘soft’ bituminous coal; an air circulation system; hot and cold running water drawn from an indoor well; an improvised shower; flush toilets; a complete, state of the art Rumford kitchen and other innovative amenities. (Kornwolfs 1453; Bachin 6; Bixler Reber 1; Pinckney 88) Roberts bore responsibility for them all.

19. The persistent style.

The fact that Roberts wrote the Directory with an English sensibility should not come as a surprise given his personal history along with the time and place he wrote it.

If the English influence on African American foodways declined over time as it would during the twentieth century in the United States then that trend should be reflected in the recipes Tipton-Martin selected to modernize for Jubilee, all the more so because she in no way emphasizes England as a culinary source and at times takes pains to minimize it.

She quotes, for example, extensively from the Historical Notes of Hess to What Mrs. Fisher Knew, including passages about the historical influences on southern food but not any of the references to Britain.

20. A multicultural jubilee.

Some of the recipes in Jubilee display an African influence or at least rely on ingredients that originated in Africa; Nigerian blackeyed pea pan fritters, Senegalese lamb shanks with peanut sauce peanut soup, a West African groundnut stew but few if any others.

At times however Tipton-Martin indulges in special pleading, for instance in her treatment of benne wafers. Benne, or sesame seeds, came to North America from Africa and represent a legitimate African influence on southern cuisine. Tipton-Martin writes in connection with her recipe that “beaten biscuits are the very first recipe in Abby Fisher’s dignified collection…. ” (Jubilee 25)

It strikes a discordant note to describe a particular recipe collection as ‘dignified,’ especially so minimalist, even terse as the transcriptions from What Mrs. Fisher Knows, even if she carried herself with great dignity. She may well have done and it appears from her associations that she did but we cannot know. And while beaten biscuits may be a vehicle for benne as an ingredient, Mrs. Fisher’s biscuits resemble the water crackers developed earlier, at the outset of the nineteenth century, as a refinement of hardtack for Royal Navy officers serving at sea. It also is difficult to ignore the fact that Mrs. Fisher does not even include sesame seeds in her recipe.

Others bear no resemblance whatsoever to anything British, including catfish or shrimp éttouffe, jambalaya of course and maque choux, both Louisiana preparations, the first a Creole creation, the second an adaptation of Native American technique.

21. An example of cultural appropriation as a good thing.

Whether or not the various dishes are attributed to British technique, the same Anglocentric pattern recurs throughout Jubilee.

Tipton-Martin discusses the sources she tapped to create her lamb curry. They include India, Jamaica, Malaysia, South Africa, the United States and unnamed French Caribbean islands. The recipe is a good standard curry combining apples, celery, bell pepper and tomato along with optional splashes of lime juice and rum. All these alleged sources other than the French holdings were British colonies and the recipe relies on curry powder, a British creation unknown to India or anywhere else before their arrival there.

The British also were the first, out of necessity, to substitute apples for mangoes and other Indian ingredients in their curries. Hannah Glasse included ‘a Currey the India way that is recognizably a curry but not particularly Indian in her Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy, first published in 1747 and the bestselling book in the world during the eighteenth century except for the bible and various pornographic texts. (Glasse 52)

By the end of the century the British, and Scots in particular, were famed for their curries; Stephana Malcolm, daughter of the Laird of Craig, “lists more that half a dozen” and describes a curry powder in her kitchen manuscript from the 1780s, while the great Isobel Christian Johnstone writing as ‘Meg Dods’ describes some twenty seven along with her formula for curry powder in The Cook and Housewife’s Manual of 1827. Her Manual incidentally is in addition to an extremely good cookbook a madcap journey inhabited by decidedly undignified characters. (Burnett & Saberi 29, 27 and passim; Johnstone 177, 190, 213, 244, 257, 314-16, 475-76)

Tipton-Martin declines to disclose the British cast of her curry, which in any event does not look much like a preparation from any of the sources she cites. The lime and rum are typical Caribbean touches but they also have been standard elements of British curries for a long time.

British cooks created the first devils during the eighteenth century but in Jubilee the passage about devilling crab does not note their influence. The same holds for the short history of the oyster loaf that Tipton-Martin dates to early twentieth century New Orleans: It first appeared as street food, in London, early in the eighteenth century. The bread pudding she properly associates with Creole cooks in New Orleans also emerged earlier out of British ovens.

To be fair, in a few instances Tipton-Martin does discuss a British antecedent but the conclusions she takes from them can be problematic. On “Biscuits for Teatime” she has

“ ….a theory that the sweet biscuits in black cookbooks generally evolved from the British practice of afternoon tea; enslaved and free people would have observed this habit.” (Jubilee 88)

Articulation itself of the notion that slaves enjoyed the ritual of afternoon tea exposes its anachronism, even absurdity.

On one particular kind of biscuit, she writes that “orange biscuits particularly can be traced to the Brits’ fondness for orange marmalade.” So far so good. Then she adds:

“But it surprised me to learn that it was the Moors who… introduced bitter oranges, the basis of orange marmalade, to Europe in the first place.

That North African heritage gives new meaning to the black penchant for a citrus fruit that was once considered exotic, expensive, and out of reach for cooks.” (Jubilee 89)

It does? Aside from the non sequitur linking the ‘penchant’ with the exotic,’ a raw orange itself does not a marmalade make, while the flavors, textures and use of the two items are unalike. This line of thought is almost as unsound as insisting that humans have an instinctive, genetic predisposition to the technique of a particular cuisine or cuisines. In any event neither Moors nor any other North Africans invented marmalade as we know it. The British had, well before the end of the eighteenth century.

As an aside the Jubilee recipe for orange biscuits is outstanding.

22. Soul food redux.

It is laudable to champion an oppressed people but lamentable to conjure a record that does not quite exist. Much in Jubilee amounts to advocacy rather than scholarship, but the argument does not quite succeed because many of the dishes described there might have arisen from any kitchen in America at any given time.

Ironically enough, a good argument may be made that the soul food which troubles Tipton-Martin represents a unique African American innovation. Another style that may represent a unique African American contribution to the foodways of the United States, the Gullah cooking of the Carolina lowcountry that Jubilee does not highlight either, also emphasizes economy. And if those innovations arose out of necessity from the humblest, most frugal of ingredients and techniques, then the accomplishment is all the more impressive.

Even soul food is not quite the culinary autarchy that has been depicted. Collards, perhaps the single most foundational and celebrated ingredient in the soul kitchen (Tipton-Martin calls her collard recipe “a totemic soul food dish”), did not arrive in North America out of Africa. (Jubilee 200)

Edward Davis and John Morgan ask their readers of Collards: A Southern Tradition from Seed to Table to “Imagine this:”

“In the early 1700s, in a village somewhere in England, a woman slipped a spoonful of collard seed into a cloth bag. Not long afterward she left her home and boarded a ship for Charleston, in the American colonies. After she arrived, she began to plant her garden.” (Collards ix)

The enterprising colonist understood the unusually efficient and nutritious qualities of her colewort, which collards then were called. As Davis and Morgan explain, by the time she was planting in South Carolina the English had begun to pronounce the leaf collard “and over the next hundred years the spelling would gradually follow suit.” (Collards x)

Collard would not be the woman’s only crop but it would be primus inter pares among her others.

“She also brought seeds for such favorites as carrots, turnips, and peas, but she knew the collard would be particularly helpful, for it would produce plants unlike any other vegetable in their ability to nourish.” (Collards x)

It was, in the harsh world of the newly settled colonist, a lifesaver, or at least lifegiver.

“Even after summer was over, each plant would continue to produce new leaves throughout the fall and winter and into early spring. So a small plot of perhaps twenty-five collard plants could provide a family of four with weekly or twice-weekly greens for up to ten months. This abundance is why our English migrant called this plant ‘cut-and-come-again’.”

‘Cut and come again”; the amazing collard plant.

‘Cut and come again”; the amazing collard plant.

Collards would take the entire south by horticultural storm. In contrast, the collard faded from favor on the eastern rim of the Atlantic.

“Although by the 1830s people who stayed in England had largely forgotten the collard and adopted in [its] place the heading form--cabbage--… in the Southern colonies the collard had become a standard feature of the fall and winter landscape as well as diet…. ” (Collards x)

Black cooks, as Davis and Morgan point out, “deserve the lead credit for the diffusion of collards across the south.” As a result, “the collard, a rather minor player in British cuisine, would become a major one in the American South because of African American culinary and nutritional wisdom.” (Collards xi) Collards, originally an authentic English staple, lost their initial culinary identity to become authentically African American. (Perkins, “Authenticity and Appropriation” 32-24)

23. An Enlightenment argument for a universal humanism.

What if race itself really were not so much of a factor in the development of anybody’s foodways? Would that be so bad? And what is ‘mindless’ about growing, cooking and serving comfort food? Growing and cooking food are subjects Tipton-Martin herself celebrates, and no culinary style should be characterized as stigmatizing either activity. And as Roberts demonstrates with flair there is, or was in his time and for decades later, dignity in service.

In a passage if not contradictory to then inconsistent with her assertion that a distinct African American culinary canon other than soul food exists, Tipton-Martin herself implicitly recognizes the possibility that it may not. Discussing what she calls “a culinary IQ that is both African and American” in a passage that itself is not quite consistent, she explains:

“You might think this intelligence is not all that different when compared to other world cuisines. And you would be right. But the idea that African Americans shared these qualities with the rest of society has been ignored for far too long. Jubilee documents these practices as they undergird an African American repertoire that is much more expansive than has been known outside our community.” (Jubilee 15)

In other words, Jubilee describes the food that prosperous black people have cooked--she refers to her upper middle class childhood and to “bougie cooking,” a term she considers accurate but rejected as “pretentious, aloof”--rather than to an African American idiom per se. (Jubilee 17)

In that respect the foodways reflected in Jubilee appear analogous to the foodways of the eighteenth century Irish Ascendancy, which were with some notable exceptions indistinct from the foodways of, in the Ascendancy case, their counterparts across the Irish Sea. (See, e.g., Shanahan; Perkins, “Is there an Irish cuisine?” and “Ascendancy foodways”) There is nothing demeaning about the composition or consumption of either derivative cuisine.

Whether or not the accomplished stature of black cooks remained unknown outside the African American community as late as 2019 may or may not be an anachronistic assumption, but it is indisputable that black cooks like black people more generally have suffered centuries of racism. Any corrective to that injustice is more than welcome and Jubilee is a good one. When Tipton-Martin speaks in The Jemima Code of a “cultural culinary dignity” that characterizes black cookbooks during recent decades the point more generally is sound regardless of the antecedents of the recipes they include. (Jemima Code 221)

24. A considerable accomplishment however defined.

A synthesis of disparate and, to many readers, surprising influences has shaped most cuisines, cooks and notionally national foodways since the early modern era of expanding literacy, trade and conquest. Some of those influences coalesced in a novel way to create recognizable regional foodways, but in the end nothing much distinguishes most of the dishes in Jubilee other than their quality. Based on them and the excerpts from historical cookbooks sprinkled through The Jemima Code, the insistence of Tipton-Martin that “some captive and free chefs should be ranked among this country’s culinary royalty” is unassailable. (Jubilee 20) She might, however, have named them.

Tipton-Martin is an accomplished cook and writer and if, based on the recipes she has selected, modified and created, she has fallen short in her effort to identify a broad African American culinary canon she has succeeded in her other goal of demonstrating that black cooks have been good cooks since their arrival in North America. Cooks of any color should spatter Jubilee with kitchen stains for years to come.

Sources:

Anon., “GORE PLACE,” SAH Archipedia, https://sah-archipedia.org/buildings/MA-01-WT1 (n.d.) (accessed 16 April 2020)

Robin Bachin, “National Historic Landmark Momination: Gore Place,” http://www.npgallery.nps.gov/NRHP/GetAsset/NHLS/70000542_text (7 January 1977) (accessed 16 April 2020)

Gauvin Alexander Bailey, “Waltham, Gore Place,” Colonial Architecture Project, www.colonialarchitectureproject.org (2020) (accessed 16 April 2020)

Patricia Bixler Reber, “Robert Roberts – author, abolitionist, butler,” Researching Food History – Cooking and Dining, https://researchingfoodhisotry.blogspot.com/2020/02/robert-roberts-author-abolitioist-butler.html (3 February 2020) (accessed 14 April 2020)

David Burnett & Helen Saberi, The Road to Vindaloo: Curry Books and Curry Cooks (Totnes, Devon 2008)

Mary Weiss Cruickshank & Susan Katz, “The Federal Period: Shaping A Nation 1780-1820,” http: www.goreplace.org/images/uploads/Shaping-the-Nation-WEBcopy2.pdf (goerplace.org 2008) (accessed 16 April 2020)

Sam Dean, “The Etymology of Gumbo, Okra, and Oysters,” bon appetit (8 February 2013), www.bonappetit.com/test-kitchen/ingredients/article/the-etymology-of-gumbo-okra-and-oysters (accessed 7 April 2020)

Abby Fisher, What Mrs. Fisher Knows about Old Southern Cooking: Soups, Pickles, Preserves, Etc. (San Francisco 1881; facsimile, Bedford MA 1995)

Hannah Glasse, The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy (London 1747; Prospect Books annotated facsimile Tones, Devon 1995)

Karen Hess, Historical Notes to Fisher, What Mrs. Fisher Knows (Bedford MA 1995)

Isobel Christian Johnstone (writing as ‘Meg Dods’), The Cook and Housewife’s Manual (London 1827)

George Everard Kidder Smith, Source Book of American Architecture: 500 Notable Buildings from the 10th Century to the Present (Princeton 1997)

William Kitchiner, The Cook’s Oracle (London 1817)

James & Georgiana Kornwolf, Architecture and Town Planning in Colonial North America vol. 3 (Baltimore 2002)

MSU Libraries, “Roberts, Robert,” https://d.lib.msu.edu/content/biographies?author_name-Roberts%2C-Robert (n.d.) (accessed 14 April 2020)

Blake Perkins, “Antecedents, authenticity and adaptation in the nineteenth century American south: A case study of Mobile, Alabama, Petite Propos Culinaires (forthcoming)

“Authenticity and Appropriation: The Southern United States and Scotland,” Petits Propos Culinaires 116 (March 2020) 26-45

“An Enquiry into the Derivation of Chowder,” Petite Propos Culinaires 109 (September 2017) 31-66

“A note on Ascendancy foodways,” www.britishfoodinamerica.com no. 36 (Spring 2013}

“Is there an Irish cuisine?” www.britishfoodinamerica.com no. 26 (March 2012)

Helen Pinckney, Christopher Gore: Federalist of Massachusetts, 1758-1827 (Waltham MA 1969)

Robert Roberts, The House Servant’s Directory: An African American Butler’s 1827 Guide (Boston 1827; Dover facsimile Mineola NY 2006)

Marcus Samuelsson, The Soul of a New Cuisine: A Discovery of the Foods and Flavors of Africa (Hoboken NJ 2006)

Madeline Shanahen, Manuscript Recipe Books as Archeological Objects (Lanham MD 2015)

Toni Tipton-Martin, The Jemima Code: Two Centuries of African American Cookbooks (Austin 2015)

Jubilee: Recipes From Two Centuries of African American Cooking (New York 2019)

John Waters, “Helen R. Pinckney, Christopher Gore: Federalist of Massachusetts 1758-1827 (review), American historical Review vol. 76 issue 5 (December 1971) 1589-90