Depredations historical & historiographical: A review of Hungry Empire by Lizzie Collingham

(published in the United States as The Taste of Empire)

1. A stylish writer confronts the British Empire and its food.

In Hungry Empire, Lizzie Collingham makes the case that “Britain’s quest for foodstuffs gave rise to the British Empire.” To that end, “[e]ach chapter opens with a particular meal and then explains the history that made it possible.” (Collingham xv) Collingham intends the conceit, which can get artificial and arbitrary, to attract readers. “If I just told the historical story,” she explains in an interview with Adam Campbell-Schmitt, “they wouldn’t be as interested. I try to tell them about real people in particular situations and how the food demonstrates why they were there and what they were doing and how these stories come together.” (Campbell-Schmitt)

To her immense credit, Collingham is a fluid writer who avoids the overwritten and needlessly obscure jargon that plagues much academic history. Unfortunately, however, there is a debit side to her methodology, and the premise underlying Hungry Empire, that the search for food fueled the imperial project, cannot withstand scrutiny.

“Food,” as Collingham herself observes, “was only one among the many commodities--textiles, dyestuffs, tin, rubber and timber--that flowed into Britain.” (Collingham xvii) Britain imported food for the same reason it imported the other commodities, to maximize the profit from its unrivaled manufacturing sector, but Collingham nowhere alludes to the doctrine of comparative advantage, an aspect of trade, not empire, that drove the economic strategy.

2. Africans in America.

One of the twenty chapters in Hungry Empire encapsulates these infirmities. It opens with an enslaved family sharing supper on a rice plantation in low country South Carolina during the 1730s. Its eloquent opening sequence, in which Collingham describes the family and the food they prepared in considerable detail, merits extensive quotation:

“In a scene that could have been transposed from Africa, a family gathered in the moonlight around the open hearth in front of their cabin on the Middleburg plantation. Tasty food at the end of the day was their principal source of comfort after working in the rice fields since first light. 1 The father was a good hunter and had found an opossum in one of his traps the previous evening; the animal was now roasting on a stick stuck in the ground next to the fire. 2 Squatting on their haunches, the family each [sic] tore a piece of maize ‘porridge’ off the mass in the big iron pot, rolled it into a ball and dipped it into a small clay jar of sauce. This evening the family’s relish was made of sorrel and watercress, which the children had collected from the edges of the rice fields. It was delicately flavoured with sesame…. 3

After they had eaten, the father went off to plant peas in their garden patch. A Carolina slave proverb that made a virtue out of necessity said that only the pods of peas planted at full moon would fill. 4 Throughout the American South, the hours of darkness were a busy time for the slaves, as this was when they carried out their own chores after the long slog of working all day for their masters…. While the father worked in the garden, the … mother was sewing a patchwork quilt out of rags…. The children were fashioning seagrass baskets that the family would sell in exchange for a little sugar or some bottles of porter…. 5” (Collingham 97-98)

Endnotes are wonderful things. They allow the reader to weigh an author’s assertion against the cited evidence and, in the case of Hungry Empire, are essential reading. Notwithstanding the explanation Collingham gave Campbell-Schmitt, her endnotes reveal that none of the people described in the passage about Middleburg is real, none of them is based on contemporaneous documentation or other evidence, none of her sources refers to the plantation itself and few of them support any of her assertions in the text.

The citation for note 1 is page 85 from the autobiography of a slave first published in 1849. He was born in 1789 and never lived in South Carolina or worked in a ‘rice field.’ The edition cited by Collingham has no page 85 and does not mention ‘tasty food,’ but does say at page 25 that food “is one of the principal sources of the comfort of a slave,” not the principal source. In the case of the autobiographer himself, it would appear that religion was his principal source of comfort because most of his text is devoted to a discussion of it. (Henson)

Note 2 has six lengthy citations, a lot of text to substantiate the claim that the slave family ate opossum because the imaginary father was a good hunter (itself odd; Collingham describes a trapper).

The first citation in note 2 is to another slave memoir, initially published in 1859; its author was born in 1780. He did not live at Middleburg either. Four citations are archeological studies, two of Monticello in Virginia; none involves Middleburg. Collingham does not provide page references for any of those four sources.

Another source for note 2, an essay by Patricia Samford, indicates that the supper described by Colliingham is unrepresentative of what slaves ate: “The wild animal and plant components of slave diets were generally small” while “domestic livestock such as pigs and cows were the principal components of the slaves’ meat diet.” (Samford 96, 95)

Another, an essay by Elizabeth Reitz and a number of co-authors, refers to the “core diet of corn, pork, and beef” eaten by slaves and notes that “the slave diet may not have been dissimilar to the planter’s diet.” Their research found remains of opossum at four of 28 plantation sites excavated; opossum was not found in South Carolina. (Reitz 167, 170, 173) When slaves did cook meat, the archaeological evidence documented by Samford indicates that they added it to soups and stews rather than roasted it. (Samford 96)

The sixth citation, to a compilation edited by Theresa Singleton, does have a reference, to an “Introduction” but to no specific page. The introduction makes no mention of opossum, but does cast doubt on Collingham’s confident description of the family supper: “Slave diet and nutrition is a very controversial topic among students of slavery.” (Singleton 7)

The citation for note 3 does not mention Middleburg, a relish or watercress but does emphasize the importance of mustard and collard greens along with guinea squash and taro in the slave diet more generally. (Carney 178) Collingham ignores those foods.

The citation for note 4 does not indicate it is an endnote. The endnote itself includes reference to slave proverbs other than the one about planting at midnight, including “a belief that potatoes should be planted at floodtide.” (Joyner 280 n14) As that fact may infer, the proverb about midnight planting is unlikely to have made a virtue of necessity. The suspicion is confirmed by the same Singleton introduction cited by Collingham in note 2. It states that the “task labor system” was “used throughout the lower Southeast in the production of tidewater staples,” like rice. Reitz et al., also cited in note 2, explains that under the task system,

“slaves might finish their work by mid-day, with time devoted to gardening, stock-raising, fishing, hunting, or other activities. It should be noted, however, that… the work day might be 15 or 16 hours long during the peak of the harvest season.” (Reitz 166)

Planting time is not the harvest season so the length of the workday did not prevent the imaginary father from sowing in daylight if he chose.

The pages cited in the source for note 5 do not discuss whether or not South Carolina slaves lived mostly outdoors, and make no mention of seagrass baskets or any purchase, whether of sugar or porter. In any event, most planters forbade their slaves to consume alcohol and a shopkeeper dependent on their custom would have been a most unlikely source of contraband beer.

3. A quest for rice?

Factual infelicities aside, the eighteenth century production of rice has nothing to do with the ‘British quest for food,’ and neither does the lengthy description of rice cultivation Collingham provides. As she notes, rice was not the first choice of South Carolina planters who, in a gratuitous aside, are described as ignorant and arrogant. “Looking for a cash crop,” Collingham explains, “they experimented with ginger, silk, vines, olive and citrus trees.” (Collingham 108, 107) She might have added indigo and tobacco, further evidence that trade itself, not the demand for food, drove the imperial project in South Carolina.

Perhaps, however, British demand did make rice cultivation profitable. Perhaps not; as Collingham herself notes, “the British rarely ate rice” so the “bulk” of the harvest was sold to German states and the Netherlands instead. (Collingham 105, 110)

The dinner that defines a chapter on seventeenth century West Africa requires scant explication to demonstrate its irrelevance. La Belinguere, “the glamorous daughter of the former ruler of Niumi,” where the meal takes place, entertains Sieur Michel Jajolet de la Courbe, slave trader and “managing director of the Compagnie des Indies.” (Collingham 57) From the language of their names it should be apparent that these people have nothing to do with Britain.

4. Imperial perfidy.

Collingham does not confine her scorn to Carolina planters and ascribes a bad motive to virtually all imperial policy. She loathes the British empire and British elites but not their subjects, who are portrayed as a mass of victims without individual agency. Churchill is a particular bugbear; Lord Cherwell, the brilliant scientist who worked tirelessly to help win the Second World War, is labeled his “henchman” and portrayed as prone to ‘mild hysteria,’ which sounds something like being a little pregnant. (Collingham 259)

Nemesis.

There is a danger in this kind of thing. “Morals in history,” as Robert Colls recently noted in the Literary Review of another writer, “are a tricky thing, and our author would have done better to dwell on their complex shifts over time.” (Colls)

The British Empire was no paradise, and taking a negative perspective on it is by no means indefensible. British administration could be incompetent, cruel or capricious. Slavery is unconscionable, although Britain was the first nation to ban the slave trade. The response to famine in eighteenth and nineteenth century Ireland was sluggish and feeble, not much better in twentieth century Bengal, when three million people died following crop failures in 1943. Racism ran endemic, and the white settler colonies fared better than the rest. Privation took a terrible toll in the new nineteenth century industrial cities. But not all was bleak, and Collingham takes an approach that is ahistorical and exaggerated, even anachronistic and unfair.

“Though,” as Ashley Parker observers, “the British Empire, and the phenomenon of large territorial empires, might seem curious now, empires have been the default setting throughout human history, which is one of the reasons why accounts that single out the British Empire for special persecution are unbalanced.” (Parker, Very Short viii)

In contrast to her condemnation of most things British, Collingham grants passes to a number of questionable customs practiced by other peoples. She passes off clitoridectomy as one of the “important female rituals” of Kenya. (Collingham 242) Imagine her invective had the British imposed the practice.

“For Chinese labourers,” she comments, “a pipe of opium was the equivalent of the British workman’s cup of sweetened tea,” citing a source that does not make the comparison and does not mention tea. (Collingham 154, 302 n44; Newman) Taking a somewhat eccentric turn Collingham considers “the opium trade, one of the Empire’s most lucrative commercial endeavours” carried on by the otherwise odious East India Company one of the few acceptable imperial enterprises. (Collingham 148, 153-54)

Thanks, East India Company!

5. Empire so broad.

Collingham’s perception of the British Empire empire lacks nuance let alone balance. She is enraged about its depredations. In addition, her conception of empire is broad to the point of misdefinition. A conflation of empire with trade and especially free trade, capitalism (variously ‘brutal’ or ‘rapacious’), commercial agriculture and the industrial revolution conjures a unitary engine of exploitation, oppression, misery and death, in the home islands and throughout not only all the imperial possessions but everywhere another nation or culture encounters the British abroad.

Collingham lacks a grip on much of her material and appears unaware of what may be the most robust debate in British historiography. The standard of living question, about the lot of workers in nineteenth century Britain, has produced a vast literature. For most ‘pessimists’ as well as ‘optimists,’ the real wages of common laborers increased, from a low calculation of 30% to a high one of over 100% from 1780 until 1850. (See, e.g., Economist; Allen) Most note that conditions in Britain surpassed conditions elsewhere in Europe. Not Collingham, and according to her the situation of British laborers was dire: It was only by 1880 that “their living standards had improved.” (Collingham 224) Before then, Britain was an industrial dystopia populated by zombies.

Even something as broadly beneficial as repeal of the Corn Laws was, in conjunction with the availability of cheap sugar, but a means of exerting social control: “The repeal of the Corn Laws and the supply of foreign wheat enabled Britain to feed its mushrooming industrial population; it may even have diverted them from social revolution,” whatever that is, “although it could be argued that the workers were simply drugged into compliance by lavish quantities of sugar.” (Collingham 224) Anything of course could be argued, but so outlandish an argument, relying as it does on the nonexistent narcotic effect of sugar, requires some kind of substantiation, which is absent from Hungry Empire.

Opiate of the masses?

Collingham repetitively argues that “Empire products helped to maintain social inequality within Britain,” a claim hard to square with one of the sources she cites without disagreement or disapproval when it suits her. (Collingham 267) In “Eating the Empire,” a thoughtful essay from Past & Present, Troy Bickham makes the case that as early as the eighteenth century “many imperial foods were almost universally available…. These foods’ ubiquity and foreignness enabled them to assume meanings that transcended boundaries of geography, class and gender in Britain.” (Bickham 73)

6. They said that?

Rage is not a handy analytical tool, and Collingham repeatedly resorts to distorting sources because her ideology trumps any concern for accuracy. She intones that “the British eradicated entire native populations,” citing a single page from an article by William Crossgrove and five co-authors. The passage in question reads “the Europeans… eradicated native agricultural systems altogether or forced native producers to grow their own food on marginal land while working on the Europeans’ plantations.” Not a pretty picture perhaps, but not genocide either and not a practice the authors delineate as peculiar to the British. (Collingham xvii; Crossgrove 226 [called ‘Cosgrove’ by Collingham])

The only extinguished native population described in Hungry Empire is the unfortunate Beothuk tribe, who appear incongruously in a chapter on Ireland. They lived on Newfoundland before the arrival of European fishermen and subsisted largely by fishing and hunting along the coasts. Their plight was unique, they are hardly representative of native populations more generally, the British were not the only nationality that reached Newfoundland, and according to the sole source on the subject cited by Collingham, their plight was not the result of genocide notwithstanding legends to the contrary. (Pastore)

7. World gone wrong.

As Ralph Pastore explains in “The Collapse of the Beothuk World,” its extinction is “unique in Canadian history.” The Beothuks never were numerous--when he visited Newfoundland in 1766 the distinguished botanist Joseph Banks noted with some skepticism an estimate of their number at about five hundred; modern scholarship points to an admittedly speculative figure of some 2,000 at the time of European contact--and alone among the native tribes of North America, “the Beothuks followed a pattern of withdrawal from contact with Europeans which culminated in their extinction early in the 19th century.” (Pastore 56, 55) That withdrawal entailed their retreat inland where, unlike the mainland, the supply of game was neither abundant nor reliable.

Even so, according to Leslie Upton, “the decrease in Beothuk population over a period of three hundred years was unspectacular,” a perspective Collingham does not address. (quoted at Pastore 56) Nor does she discuss the evidence cited by Pastore “that in at least three instances before the arrival of Europeans” in Newfoundland “prehistoric native populations have become extinct--very likely because of changes in the availability of vital food resources.” (Pastore 55) In blaming the demise of the Beothuks on the British she has ignored a considerably more complex chain of events, a chain her sole source describes in detail. As an aside it may be apparent at this point that the Beothuk tragedy has next to nothing to do with empire.

8. An empire informal… or phantom.

Collingham claims that “for the first eighty years of its existence, the United States remained an important member of Britain’s informal commercial empire,” citing a page from her source that discusses the search for a northeast (via Lapland and Moscow) and northwest passage to Asia between 1552 and the 1630s. A different page from the same source warns against the kind of oversimplification in which she indulges:

“[I]ndependence led to an acceleration of the process of differentiation that both characterized and challenged the Anglo-American world” but “it is important not to exaggerate the role of independence in this process…. The role of British investment might suggest that the new state was, at least in some respects, part of what was to be termed the informal empire, but this does less than justice to the strains in the relationship.” (Collingham 141; Black 42, 142)

Those strains would include Jefferson’s embargo on British goods and the small matter of the three-year long War of 1812.

9. The pity of war.

Collingham has little interest in the tactical or strategic considerations of warfare and less understanding of them. Hungry Empire serially scorns the priority Britain placed on defending the home islands during the Second World War: Among other felonies, Britain should have risked defeat by funneling more food to the reaches of empire.

According to Collingham, the empire “came to Britain’s rescue.” (Collingham 255) “The empire,” she argues, “was, in fact, the source of Britain’s strength” during the Second World War “ . Australian warships fought in the Mediterranean; South Africa supplied minesweepers, bombers and fighter aircraft; the Indian air force fought the Japanese…. ” (Collingham 254) Once again, the cited source says something different from what Collingham claims it says, and while her assertions that Australia, South Africa, India and the other imperial possessions all contributed to the war effort are true, they also are presented in a misleading manner.

Her source, The British Empire in the Second World War by Parker, nowhere says the empire was the source of British strength. Instead, he makes a legitimate point:

“The British Empire defined Britain’s war between 1939 and 1945. It was a war fought in imperial theatres by imperial forces, all of which were dependent upon sea power and Britain’s capacity to move food, goods, munitions and troops from one side of the world to the other…. London, the nerve centre of a global Empire, had to coordinate the war effort of over sixty countries. It did so in a stunningly successful example of what today would be called coalition warfare. Bringing shared experiences to people across the world by virtue of the bonds of Empire, the war was one of the most significant globalizing experiences of the twentieth century.” (Parker ix)

The empire was in that sense a paradox, an ungainly source of weakness--vulnerable sea lanes, attenuated lines of communication requiring substantial investment and resources--as well as strength. Its war was a cooperative effort among nations with shared ties and interests that required the construction of a coalition, not the exploitation by one feeble nation of sixty vassals that Collingham portrays. (Collingham 260)

10. Orders of battle and orders of magnitude.

Parker believes the contributions of the soldiers and civilians of many imperial entities have been overlooked. His brief lies in redressing that wrong, and he executes it with exemplary results. His characterization of contributions to the air and naval war is typically balanced. As Parker explains in the passage that Collingham carefully paraphrases:

“The air and naval forces of the Dominions, India and the Colonial Empire, in supplementing British and American forces, also deserve greater attention. Commonwealth airmen formed nearly half of Bomber Command’s strength in Europe. In the Mediterranean Australian warships made an important contribution, as did South African minesweepers, bombers and fighter aircraft…. And by the end of the war the Royal Indian Air Force had 30,000 personnel and nine squadrons of fighter aircraft engaged against Japan.” (Parker, Second World War 3)

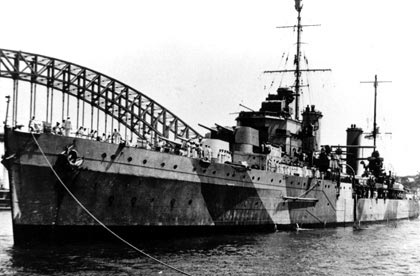

Quantification of the Australian and South African contributions sets them in context. At the onset of war, the Royal Navy remained the most powerful on the planet. Its Mediterranean Fleet included four battleships, an aircraft carrier, nine cruisers, twenty-five destroyers and forty-nine submarines. Another ten destroyers operated out of Gibraltar.

Over the subsequent five years of conflict, the Royal Navy also maintained other large fleets, including the Home Fleet, Atlantic and Pacific Fleets, and escorted Arctic convoys and performed other duties to maintain the vital sea lanes. The number of its ships in the Mediterranean varied depending on tactical dispositions including strike plans, convoy escort and amphibious operations.

During August 1943, for example, various formations operating there had expanded to six battleships, three carriers, five escort carriers, two cruiser squadrons of multiple ships, two cruisers out of Gibraltar, six destroyer flotillas, two generally but not always smaller destroyer divisions, three submarine flotillas and numerous escorts and auxiliaries. (naval-history.net)

At the onset of war, the Royal Australian Navy had no battleships or carriers. It consisted of six cruisers and five destroyers, all British built, along with a number of auxiliaries. Australian warships did join the British in the Mediterranean during 1939, and their crews fought them well.

At its peak of operations, the Royal Australian Navy deployed five of its ships in theater, a light cruiser and the “scrap iron flotilla” of four obsolete destroyers completed in 1918. The last survivors had sailed for the Pacific by the end of 1941 to defend Australia following the initial Japanese offensives against the western powers. (see, e.g., awmlondon; gunplot) So it would appear accurate to concur with Parker that the Australian contribution to the naval war in the Mediterranean, while valorous, was indeed supplemental.

As for South Africa, its sailors did man some British built ships, all smaller than a destroyer and most deployed to protect South African ports. South Africans also served in the Royal Navy, while its pilots flew aircraft built in Britain and the United States: South Africa did not ‘provide’ vessels or aircraft. (see, e.g., navy.mil.za) The Indian Air Force did fight Japan but not to rescue Britain: The Japanese had invaded India so it would appear reasonable to have chosen to defend the place and avoid the savagery and killings that characterized the Japanese occupation of conquered countries.

As an aside, thousands of Indians fought for Japan in the Indian National Army, a fraction of the 2.6 million who joined the British Indian Army, which remains the largest volunteer forced ever assembled and provides some indication that the Raj was not universally loathed by its subjects.

11. Guilt by omission.

The recapitulation by Collingham of events like the Australian naval role in the Mediterranean, in common with her discussion of rice cultivation and a lot of other digressions, has scant bearing on the putative subject of Hungry Empire other than to present Britain in an unflattering cast. For the same reason, Collingham omits inconvenient facts from her analysis. Britain did not bleed its empire to fight the war. Canadian farmers profited from the sale of their grain. “India,” as Parker notes, “benefited financially from the war and the financial tables were dramatically turned. In 1939 India had owed Britain £250 million, but by 1945 Britain owed India £1200 million.” (Parker, Second World War 47)

Britain not only repaid the debt in full but also extended the duration of rationing at home in an effort to meliorate postwar food shortages in southwest Asia, hardly hallmarks of a unidimensional and exploitative oppressor.

‘Eradicated’ in connection with genocide, ‘informal empire’ in connection with the United States, ‘source of British strength;’ these words are wrenched from their context to contort and even contradict the cited secondary sources. This is history by palimpsest, in which the outlines of earlier studies are scraped and scratched to eradicate anything inconvenient in an attempt to promote an ideological agenda.

The distortion of source material in Hungry Empire exaggerating the imperial contribution to the war effort is not an isolated infraction in military terms.

12. The shipping news.

Collingham decries the amount of shipping allocated by the British to the Atlantic as opposed to Indian Ocean during the Second World War as inhumane and incompetent, the product of an irrational obsession. Inhumane, she argues, because more shipments of food would have ameliorated hunger throughout the empire; and incompetent because the German submarine campaign was inconsequential. Collingham cites Why the Allies Won by Richard Overy to argue that “the German blockade never seriously threatened to bring Britain to its knees.” (Collingham 254 citing Overy 31)

The citation is misleading to the point of misrepresentation: Overy says no such thing at the cited page or anywhere else. Instead, he maintains that German submarine and aerial operations “were sufficient to create a debilitating haemorrhage.”

He explains that it was only after delay and with reluctance that Britain concentrated on the Atlantic supply lines, and that the German blockade had indeed threatened to defeat Britain.

Unlike Collingham, Overy cites data in support of his conclusion:

“During 1940 over a thousand ships were sunk, totaling 4 million tons, a quarter of British merchant shipping…. British trade was slowly bled white: 68 million tons were imported in 1938, 26 million in 1941. When figures for February were released Churchill finally moved to give anti-submarine warfare priority over everything else. On 6 February he announced that Britain was now fighting ‘the Battle of the Atlantic’ which he regarded with justice as ‘the real issue of the war’ for Britain.” (Overy 31)

“By late 1941 the British merchant fleet began to decline steadily, while the long hauls necessary to avoid danger-spots wasted vital shipping capacity. Over the year 1,299 ships were sunk, and over half their crewmen were lost. Still bereft of naval allies, Britain faced the prospect of isolation from American supplies and the loss of the Mediterranean.” (Overy 32)

Whether or not Overy’s analysis is correct, and nothing indicates that his judgment is wrong, he does not minimalize the submarine threat. As for the welfare of the empire, without access to the Mediterranean, Britain would have had difficulty supplying India, and had Britain lost the Battle of the Atlantic, it also quite obviously would have lost the capability to allocate anything at all, let alone shipping capacity for food, to its erstwhile possessions.

13. Matters of fact.

Factual errors abound along with the distortion of sources. Collingham states that the cheese purchased for Royal Navy ships in 1545 came from Gloucester or Cheshire. As two of her own sources indicate, however, that was not the case. “The Navy,” according to the authoritative N.A.M. Rodger, “had always issued Suffolk cheese…. There were frequent complaints against it, and in 1758 the decision was taken to switch to Cheshire and Gloucester cheese.” Janet Macdonald concurs, adding that the Victualling Board also purchased Cheddar and Warwickshire cheese beginning that same year. (Rodger 85; Macdonald 31)

The insurrection that began during 1641 in Ireland was not, as Collingham maintains, “an ethnic conflict between the native Catholic Irish and the new Protestant settlers.” Ethnicity is not religion, Irish ethnicity was and is not binary, and people of the same ethnicity fought on different sides. The Old English, for instance, settlers themselves and Catholic, owned a third of the land at the outbreak of war and fought on the Irish side against the English administration. (see, e.g., Clarke passim)

Back to the subject of trade (not empire), it is equally oversimplifying things, and at this point anachronistic, to refer repeatedly to a “triangular trade” in slaves, molasses and rum during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

Rum is not, as Collingham assumes, “one of the most calorific of all spirits” because it is “[d]erived from sugar.” All spirits are derived from sugar, whether refined from cane, barley, corn, potatoes, wheat or anything else, and share similar calorie counts, although by some analyses rum is slightly less calorific than whiskey or gin of the same proof. (Collingham 133) The iconic English beer is India Pale Ale, not ‘Indian’ pale ale, and never was described that way. Nor is gumbo, which originated in Louisiana and draws from all its diverse cultures, “distinctively African.” (Collingham 273)

Plimoth Plantation today.

Collingham claims that seventeenth century Plymouth “was given a boost… when a group of London merchants founded the Massachusetts Bay Colony,” but Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay were different, and rival, enterprises that shared no resources. (Collingham 31)

14. An appetite for anachronism.

Anachronistic epithets litter Hungry Empire. John Adams, perhaps the earthiest of the American founders along with Franklin, is a “snooty Harvard graduate;” the “cheapskate British” feed their workers a uniform, and meagre, ration worldwide. Unaccountably, this same food that caused malnutrition in West Africa sustained the armies that prevailed in the Western Desert: “The British soldiers in North Africa were given the same ration that had fed the Empire’s sailors, explorers, cowboys, indentured labourers and pioneer settlers.” (Collingham 136, 242-43, 253) Notwithstanding so confident an assertion, which she repeats throughout Hungry Empire, Collingham offers no source for so implausibly static and uniform a diet across the entire globe for hundreds of years, nor does she explain how some “given the same ration” starved while others flourished.

15. The horrors of British food.

British food gets the bash more generally too. In contrast to all the appealing exotica abroad, some of which she says the British extirpated, Collingham disdains the historical foodways of Britain. As with other subjects, she also misdescribes them.

Beginning in the seventeenth century, she maintains, “as spices disappeared from English food, it became increasingly plain.” An “expulsion of spices from savoury food” transpired because as they became affordable to virtually anyone, nobody wanted the spices anymore; “loading one’s food with cinnamon and clove lost its ability to signal wealth and status.” (Collingham 75, see 80) For the newly impoverished laborers of urban nineteenth century Britain, this trend would culminate in the “unimaginative food culture based on the industrial ration of flour, sugar and tea.” (Collingham 204)

It is a peculiar position, especially because Collingham has written a book on curry, which had conquered the kitchens of Britain during the eighteenth century (Bickham 103), and no citation for the argument appears anywhere in Hungry Empire. Then again Collingham makes the unfounded but predictable aside that “British cookery was at its most adventurous, interesting and innovative when it incorporated colonial dishes.” (Collingham 126)

Highly spiced dishes have been a hallmark of British foodways. Throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, for example, devils made fiery with mustard, cayenne, sometimes highly spiced chutneys, then eventually Worcestershire and other condiments remained all the rage for coating birds, bones and meats for a flash under the grill. They are unknown in other cuisines.

Collingham manages to contradict herself by discussing a cookbook published during 1791 in connection with one of the highest status, if not the highest status, foods of its era. A recipe from The Lady’s Complete Guide; or Cookery in all its Branches by Mary Cole seasons turtle soup with cayenne, clove, mace and nutmeg. (Collingham 124)

Hannah Glasse, whose Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy first appeared in 1747 and was the bestselling cookbook of the eighteenth century, betrays a fondness in dish after savory dish for allspice, cayenne, clove, mace, black and white pepper, and other spice including seeds of caraway, coriander and fennel. She is no outlier. Other eighteenth and nineteenth century cookbook authors follow suit, including many more than Richard Briggs, Isobel Christian Johnstone (‘Meg Dods’), Charlotte Mason, Sarah Phillips, Elizabeth Raffald and, later, Eliza Acton.

Collingham repeats the weary wheeze that curry powder is a bad product, a blanket condemnation rejected by Madhur Jaffrey and others. Somehow curry powder “forced” miners in British Guyana during 1993 “to prepare dishes that were more generic than those they would have made in their homeland” although in fact they were native Guyanese “descended from African slaves.”(Collingham 205, 200)

Even British flags printed on food packaging to denote country of origin are sinister, a “celebration of local food production that smacks uncomfortably of 1930s nationalism.” (Collingham 272)

It would be nationalistic, except it is made in Philadelphia.

16. The fitting finale.

Works of fiction bookend the last chapter of Hungry Empire; first, a fanciful meditation on Christmas pudding from 1850 and last, a curry described in, of all places, Bridget Jones’s Diary. Ironically and inadvertently they are appropriate selections. Between these two sources Collingham also does her reader the favor of citing Hitler. Because his “analysis” is “unfettered by moral scruples” he offers reliable insight about Elizabethan Ireland, which he never addressed, and on the westward expansion of America, which was not a British undertaking. (Collingham 271) That pretty much says it all.

Sources:

Robert Allen, “The Great Divergence in European Wages and Prices from the Middle Ages to the First World War,” Explorations in Economic History 38 (2001) 411-47

Anon., “The Battle for the Mediterranean, 1917-18 & 1940-43,” www.awmlondon.gov.au (2017; accessed 2 January 2018)

Anon., “History of the SA navy,” www.navy.mil.za (17 August 2015; accessed 2 January 2018)

Anon., “Real wages in Britain,” The Economist, www.economist.com/blogs/freeexchange/2013/09/economic-history-0 (September 2013; accessed 7 January 2018)

Anon., “Royal Navy in the Mediterranean,” www.naval-history.net/WW2CampaignsRNMed.htm (accessed 3 January 2018)

Anon., “Scrap Iron Flotilla,” www.gunplot.com (2003; accessed 2 January 2018)

Troy Bickham, “Eating the Empire: Intersections of Food, Cookery and Imperialism in Eighteenth-Century Britain,” Past and Present 198 (2008) 71-109

Jeremy Black, The British Seaborne Empire (New Haven 2004)

Alan Campbell-Schmitt, “‘The Taste of Empire’ Retraces Britain’s Colonial History Dish by Dish,” www.foodandwine.com/news/taste-empire-book-lizzie-collingham (5 October 2017; accessed 28 December 2017)

Judith Carney, Black Rice: The African Origins of Rice Cultivation in North America (Cambridge MA 2009)

Aidan Clarke, The Old English in Ireland, 1625-42 (Ithaca NY 1966)

Robert Colls, “Arguments for Democracy,” Literary Review 459 (November 2017)

David Conroy, In Public Houses: Drink & the Revolution of Authority in Colonial Massachusetts (Chapel Hill 1995)

David Cordingly, Under the Black Flag: The Romance and Reality of Life Among the Pirates (New York 2006)

Martyn Cornell, “The First Ever Reference To IPA,” http://zythophile.co.uk/2010/03/29/the-first-ever-reference-to-ipa/ (29 March 2010; accessed 3 January 2018)

William Crossgrove et al., “Colonialism, International Trade, and the Nation-State,” in Lucile Newman (ed.), Hunger in History (Cambridge, MA 1990) 215-40

Hannah Glasse, The Art of cookery Made Plain and Easy (Prospect Books facsimile 1994; orig. publ. 1747)

Josiah Henson, The Life of Josiah Henson, formerly a slave, now an inhabitant of Canada, www.docsouth.unc.edu/neh/henson49/henson49.html (Chapel Hill 2001; orig. publ. 1849)

Ashley Jackson, The British Empire: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford 2013)

The British Empire and the Second World War (London 2006)

Charles Joyner, Down by the Riverside: A South Carolina Slave Community (Urbana 1984)

Janet Macdonald, Feeding Nelson’s Navy (London 2004)

Craig Muldrew, Food, Energy and the Creation of Industriousness (Cambridge, England 2011)

R.K. Newman, “Opium Smoking in Late Imperial China,” Modern Asian Studies Vol. 29 No. 4 (4 October 1995) 765-94

Richard Overy, Why the Allies Won (London 1995)

Ralph Pastore, “The collapse of the Beothuk world,” Acadiensis vol. XIX no. 1 (1989) 52-71

Elizabeth Reitz et al., “Archaeological evidence for subsistence on coastal plantations,” in Theresa Singleton, The Archaeology of Slavery and Plantation Life (London 1985) 163-91

N.A.M. Rodger, The Wooden World: An Anatomy of the Georgian Navy (London 1986)

Theresa Singleton, “Introduction,” in Singleton (ed.), The Archaeology of Slavery and Plantation Life (London 1985)

Nuala Zahedieh, The Capital and the Colonies: London and the Atlantic Economy (Cambridge, England 2010)