A review of A History of English Food by Clarissa Dickson Wright & its reviewers

with commentary on the character of some newspapers.

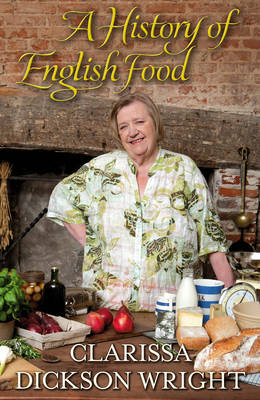

1. A portrait of the author.

Clarissa Dickson Wright has written a new book in time for the Christmas season and it is a stinker. A History of English Food is in reality nothing of the kind, but instead substitutes speculation and snobbish reminiscence for any modicum of research or analysis. Judged by her memoir, Spilling the Beans, Dickson Wright is a mean old bird intent on settling scores, dropping names, taking credit and boasting. Even worse, she would appear to be one of those reformed alcoholics who rattles on, and on, about AA and is insufferable on the subject of booze.

She has had a difficult life and recounts the many “dreadful” things she has experienced, but both before and after drinking herself into homeless destitution following the death of a lover she had been quite the barrister, at least in her telling. It therefore is a bit of a surprise that the brief she has written extolling herself is so unconvincing.

Dickson Wright did not much like the law, an understandable enough sentiment, but her resentment at dealing with money strikes a discordant and whiny note. We learn that she possessed sufficient intelligence to be “the youngest woman ever called to the bar,” but displays an astonishing lack of common sense in recounting that “nobody told me I had to record every billed hour and I soon ran into problems making up the bills. I hadn’t really expected to have to tackle this area of the work and tempers frayed.” (Spilling photograph caption between 120-21, 198)

Commerce of course is distasteful, but because Dickson Wright realized that “after all I owed nothing to anyone but myself” and did need money, which after all comes in pretty handy down here, bub, she quit the law and returned to a prior job with an Edinburgh bookstore: “It is generally agreed that it was me who turned Books for Cooks into a household name worldwide.” (Spilling 198) Perhaps the Editor alone had missed that phenomenon.

No pennies in heaven.

2. Class warfare.

Dickson Wright is nothing if not confident in her views, however, and a page later we also learn that “[t]hankfully West Indians are used to being berated by large angry women.” (Spilling 199)

A History of English Food also contains a slew of what Rachel Cooke in The Guardian calls these “gruesomely snobbish asides” and it is predictably derivative in its prejudices, for example of Elizabeth David in despising Mrs. Beeton.

The reviews, by Cooke and other British journalists, are more amusing and revealing than the book itself. It may be clichéd to observe that some clichés became such because they are true, but in this case temptation proves irresistible. British newspapers have reputations cast in steel, and in less than 700 words, each reviewer has managed to embody the putative identity of the one where she works.

Aside from the typographical errors that gave it the classic Groiniad nickname, mention the Guardian and people conjure a vision of robust leftward bias; Cooke fits squarely in the frame. The snobbery that flits through A History of English Food distresses, even angers her, which causes a certain failure of perspective. It may be true that Dickson Wright “cannot be bothered to engage with how and why most of us eat--mostly, I imagine, because she does not know,” but as the title indicates, the remit of A History does not require analysis of contemporary middle class foodways.

Cooke cannot resist sarcasm (“Naturally, she is devoted to the Georgians…. ” and their excess, but “Oh! The awfulness of the new class who didn’t properly know how to run their servants!”) and that becomes tiresome, even within a review running to under two pages. Tiresome too is the Guardian’s archaic obsession with class in general, a theme that also recurs in Cooke’s short review both through strained argot (during the twelfth century, “people also eat pike, eels, pigeon, deer, and, er, badger…. ”) and stale imagery (“ah, the good ole charcoal burners who lived in the woods of her childhood--thrown in for those, like her, never leave the house without their rose-tinted sunglasses.”).

![]()

All of this may be irritating but none of it is unfair. A History of English Food is indeed a “half-baked survey” and Cooke properly disdains the rampant speculation; Dickson Wright does sprinkle “the phrases ‘I’d guess’ and I’d suspect’ as merrily as salt, and over every chapter--without ever, quite, daring to turn the whole thing into polemic.” Cooke, however, could have diluted the polemic that informs her own review and extended her reach a little too. She finds Dickson Clarke’s praise for Antony Worrall Thompson ‘bizarre,’ but there he looms in Spilling the Beans, “a regular customer hoovering up imported American books” from the shop. She liked his food as well as his patronage, and “always regarded Antony as an underrated chef.” (Spilling 205)

Nonetheless Cooke concludes on an exemplary note by recommending two good alternatives to A History of English Food:

“All of the information in this book can be found elsewhere, and much better done, too. For starters, try Kate Colquhoun’s Taste: The Story of Britain Through Its Cooking. If this goes down well [but Editor’s note: more ugly argot], move swiftly on to Dorothy Hartley’s classic Food in England, a work of true scholarship that has never been out of print since it was first published in 1954.”

And so it is, although Cooke could have mentioned the characteristically English eccentricity that infuses Hartley’s work.

3. Anti-intellectualism in British life.

On one point the biases of the Guardian and its Tory counterpart converge. Just as extremes of Fascism and Communism converge to encompass totalitarian nightmare, the extreme left and right in Britain share a reflexive and militant anti-American strain, the Guardian because the United States is insufficiently (or not at all) socialist and The Telegraph because the place traditionally eschews social deference and its fellow traveler, fusty culture.

Otherwise the papers remain locked in merry ideological conflict. That fact is reflected in the rather mindless review that Jane Shilling gave A History in The Telegraph. She approves of the book for its “firmly chronological line across the landscape of culinary history” and calls it “magnificently eccentric and robustly informative…. It is an impressive tour of the horizon of a well stocked mind.”

The tone is Tory confident as well as bursting with cliché, but we get no specific examples, and might be forgiven for noting the know-nothing stance of shire Toryism. The old ways are the good ways and narrative is all, provided it remains uncomplicated. No fancy cliometrics, postcolonialism or analytical acuity allowed; the verities might suffer if we think too much or too hard. Perhaps Shilling knows little about the historiography of food, or bows to Dickson Wright because of her status as One of Us; she is, after all, a champion of blood sport and privilege.

Nobody boasts better anti-intellectual credentials than the British tabloid press, and the Daily Mail honors that tradition in two reviews of A History. Neither discloses a conflict of interest; Dickson Wright regularly writes for the Mail. The first, by Val Hennessy, is a sort of fawning middle school book report. It recapitulates without analysis a few anecdotes, none in the least representative of national foodways, from Dickson Wright’s timeline. Most of them describe gluttony, including one about “Henry VIII’s 1517 shindig.” Hennessy also gushes that “[o]ne thing you can say for food writer and TV celebrity Clarissa Dickson Wright is that she jolly well knows her stuff.” That is because she eats a lot, and has eaten lots of strange things: “Just take one look at the woman! When it comes to food she is indefatigably hands-and-teeth on.”

It is unclear how heft enhances the qualifications of a historian; Hennessy does not elaborate on her dubious logic. She does add the enlightening observation that “Clarissa” does not mention “one interesting fact. During the war” Hennessy’s “mum’s rural Norfolk aunt would regularly send her, by Royal Mail, dead rabbits wrapped in brown paper, stamps stuck on, with their furry heads and back legs poking out.” It would be difficult to comment further on criticism of this order.

The second says nothing of substance about the book but does relish the disdain of its author for Heston Blumenthal, the innovative and admired chef at Dinner who has taken early modern British foodways and transformed them through contemporary technology and his own self-taught style. The headline to the story thunders “Heston’s Got It Wrong” because Dickson Wright considers his food unpalatable and unEnglish, not what they really ate, not at all. This stance requires cultural occlusion on a colossal scale. We can and cannot replicate the flavors of that foreign country, the past, in the sense that plants and animals and spits and stoves and people have changed; they also, however, have left written records of how they cooked and what they ate. It would be ridiculous, however, to cleanse and ossify a cuisine in a hopeless attempt to outlaw innovation.

Incidentally Dickson Wright hates Jamie Oliver, both because he engaged in promotional work for a supermarket chain and for his tireless attempts to improve the food served to schoolchildren. Speculation and foolishness dominate that front too. Of Oliver she has said that “his restaurants are very lacklustre--I’m told. I don’t know. I don’t eat in them… I don’t want to risk being poisoned.” Of his effort to improve the nutrition she claims without evidence that “Children don’t eat salad! All it succeeded in doing was getting more schools to close down their meal functions.” These erudite pronouncements also appeared in the Daily Mail, back in 2008.

4. The sin of omission.

If nobody could accuse a tabloid of lacking a point of view, conventional wisdom would fail to find one at The Independent, a paper founded late in the twentieth century in attempt to occupy the heights of objectivity. Instead it seems just to lack the depth or punch of the older broadsheets. True enough to form, The Independent takes no side in the debate over A History of English Food. Alone among our examples, it does not review the book.

5. A rare good deed by News Corporation.

Finally for our immediate purpose looms The Times in all its fame and Murdoch-imposed tarnish. It remains for the most part a literate publication, however, and we are insufficiently biased against its grotesque ownership to deny that the paper is livelier than it was before their acquisition. The Times retains its stance as paper of record in our microstudy by giving A Taste of History the longest review.

It comes courtesy of none other than Kate Colquhoun, the historian praised by Rachel Cooke in the Guardian. The Editor is of two minds about Colquhoun, an admirer of Taste but uneasy with the ahistorical and politically correct ideology of her subsequent work on World War II. Colquhoun is indisputably an able scholar, and her measured review of A History ranks as best in show. It also leapt first out of the blocks.

Colquhoun guides us through some of the history but wears her erudition lightly. She politely disapproves of the speculation decried by Cooke and draws several vignettes to pique our interest. As she explains without stridency, “the constant repetition of ‘I suspect’ or ‘I’d guess’ often foreshadows historical ‘facts’ that are, at the very least, contentious and sometimes plain wrong--there isn’t a contemporary historian who would contend, for instance, that medieval peasants ate no vegetables.”

No veggies?

It felt good to learn that the mother of Henry VII, Margaret Beaufort, acted both as patron of the great printer Caxton and proselytizer of taste: “Without her, we might not have had all those early manuals that reveal so much about the way they ate, let alone the etiquette that forbade spitting at table, or scratching one’s arse.”

Colquhoun is sufficiently gracious to give Dickson Wright some due, noting with approval her television programs and promotion of traditional foods. Unlike the angry Cooke, her tone is of regret. Dickson Wright might, Colquhoun thinks, have brought “to our food history a brightly nuanced perspective.” But Dickson Wright is, she infers, not only a dilettante but also a bit of a shit: She “draws heavily on the work of others (without decently acknowledging it in notes) but refuses to look further or deeper than the oft-repeated facts.”

Given Dickson Wright’s outsized personality, Colquhoun justifiably finds it lamentable that she does so like to bring her subject to life. Lamentable but not mysterious:

“Her book is clearly designed for the Christmas market. Instead of an intelligently textured version of our kitchen history, though, we have been served an opportunistic dish that turns out to be as naïve and unsatisfying as unseasoned mash potato [sic].”

Spilling the Beans is something like attending a NASCAR race, waiting for a hockey fight or witnessing a crash. We have an untoward fascination with incipient disaster, and that instinct makes it hard to stop reading the book; something unspeakably awful promises to appear with every turn of a page. A History of English Food, however, is merely an irritating bore.

Sources:

Anon., “Heston’s Got It Wrong,” Daily Mail (31 October 2011)

Kate Colquhoun, “A History of English Food by Clarissa Dickson

Wright: From almonds and spices to Seville oranges,

England has always embraced new flavours from around

the world,” The Times (16 October 2011)

Rachel Cooke, “A History of English Food – Review: The

lofty tone of Clarissa Dickson Wright’s ed survey of our

national cuisine leaves Rachel Cooke with a bad taste in

her mouth,” the Guardian (28 October 2011)

Clarissa Dickson Wright, Spilling the Beans (London 2007)

A History of English Food (London 2011

Val Hennessy, “Is there ANYTHING Clarissa won’t eat? A History

of English Food by Clarissa Dickson Wright,”

Daily Mail (21 October 2011)

Olinka Koster, “Battle of the Frying Pans: TV Chef Clarissa

Dickson Wright attacks ‘force for spin’ Jamie Oliver,” Daily Mail

(7 September 2008)

Jane Shilling, “A History of English Food by Clarissa Dickson

Wright: review,” The Telegraph (26 October 2011)