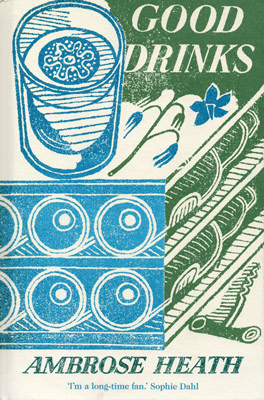

Some strange & wondrous drinks from 1939.

That was the year Ambrose Heath published Good Drinks in Britain, hardly an auspicious one for the cocktail culture. Undaunted, at the outset he outlines “all those occasions when drinking is desirable” which, it turns out, are just about all occasions:

“on a winter’s evening by the fire, on the shady verge of the tennis-court, at a party, in a pub; with friends, or acquaintances and those even dearer, wherever they happen to be together: to the advancement of the brewer and the wine merchant, and the confusion of all dull dogs.”

Heath divides his drinks into twenty nine hard and soft categories including “Curious Drinks” which given the overall cast of his book looks at times like a redundant description.

While Heath justifiably includes the “Split Worcester,” consisting of a “small wineglassful of Worcester Sauce with a split Soda” among the curiosities, he might also have placed his “Lawn Sleeves” there, and not only for its nondescriptive name. The drink adds sugar to the already sweet Sauternes, an expensively luxurious wine that should not suffer adulteration, especially in the form of the sugar. The sweetening is but the starting point: The Lawn Sleeves is (are?) spiced with allspice, cinnamon, clove, mace and nutmeg, diluted with boiling water but then thickened with calf’s foot jelly.

This last ingredient is not quite the outlier it appears. David Wondrich for one cites the use of cowheel jelly as a textural agent for punch that gives the drink an unctuous quality akin the salutary effect of clarification by curdled milk. Unaccountably enough Wondrich prefers the drink made with the bovine jelly. There is, as is said, no accounting for taste.

Most of the other hot drinks are nearly as strange, and in some cases Heath himself sounds skeptical about them. His instruction to make “Brown Caudle or Scots Aleberry,” a mixture of ale steeped in oatmeal then strained before the addition of sugar, “Wine and Seasonings to taste” ends with an indication that he has not himself tried it: “So writes Meg Dods,” itself an in-joke because as Heath doubtless knew ‘Dods’ was a fictive character conjured by Sir Walter Scott whom the brilliant Isobel Christian Johnstone appropriated as the nom de plume for her riotous but informative cook and housekeeper’s manual.

He cites another cultural polymath who also lived in Edinburgh, George Saintsbury, as the source for “The Bishop” which, Sainsbury laments, “is, as I have found more people not know than know in this ghastly thin-faced time of ours, simply mulled Port.” Sainsbury is as playful as Heath and in fact his formula for mulled Port is not all that simple, embedding as it does a number of options with both satanic and seductive sides:

“You take a bottle of that noble liquor and put it in a saucepan, adding as much or as little water as you can reconcile to your taste or conscience, an Orange cut in half (I believe some people squeeze it lightly) and plenty of Cloves (you may stick them in the Orange if you have a mind). Sugar or no Sugar at discretion, and with regard to the character of the wine. Put it on the fire, and as soon as it is warm, and begins to steam, light it. The flames will be of an imposingly infernal colour, quite different from the light-blue flicker of spirits or of Claret mulled. Before it has burned too long pour it into a bowl, and drink it as hot as you like. It is an excellent liquor, and I have found it quite popular with ladies.”

We can neither reconcile watering Port to our collective conscience nor stomach sugaring “that noble liquor” and forsaking those options but otherwise following Saintsbury’s lead does create a bracing drink for a dark wintry day.

Good Drinks follows the prescription with an explicit game, “A Small Collection of Quotations Apposite to the Contents of this Book” whose authors only are revealed 219 pages further inside. One of them, on the painter George Moreland from Gilbert and Cuning in 1907:

“Drinks for one day at Brighton (having nothing to do):

before Breakfast:

Hollands gin

Rum and Milk

Coffee (Breakfast)

before Dinner:

Hollands

Porter

Shrub

Ale

Hollands and Water

Port Wine with Ginger

Bottled Porter

at Dinner and after:

Porter

Bottled Porter

Punch

Porter

Ale

Opium and Water

Port Wine (at Supper)

Gin and Water

Shrub

Rum on going to Bed.”

And Moreland was not a surrealist….

Another quotation, from David Copperfield: “But punch, my dear C----, like time and tide, waits for no man.” Heath leaves little doubt that drinking is a solemn duty and sacrament.

He is, however, ambivalent about liqueurs, and who could blame him? While “delicious as flavours” they “are admirable for those who like them.” On wine he is self-effacing:

“The art of drinking Wine and understanding it implies a range of knowledge and experience which unfits it for inclusion in this volume…. It has been thought best, therefore, to refer those readers who are interested in or seek knowledge of the subject to the list of books dealing with it, which appears at the end of this anthology….”

As these few examples indicate, Heath and the sources he has selected are congenial companions. As an entirely unnecessary bonus, Good Drinks includes quite a lot of other good drinks along with some unexpected omissions. Heath has no whisky mac, cold instead of hot but equally as welcome as mulled Port of a winter’s day, but his “Havelock” is a sort of brandy mac that substitutes the grape spirit for pairing with the ginger wine.

Nor does Heath know the Bloody Mary: His hard “Tomato Cocktail” features Sherry but not vodka along with lemon, Worcestershire and the unlikely addition of cream, an appealing surprise.

He does describe lots of different Martinis, although he calls one of them “Gin and It,” another the “Golf” (it adds “2 dashes Angostura Bitters” to the gin and vermouth) a third the “Homestead” adding an orange slice and a fourth, a perfect martini that uses both dry and sweet vermouth simply “Perfect.”

Heath has not overlooked Black Velvet, half Champagne and half Guinness, the British classic for service with oysters that is virtually unknown in the United States. His twenty punches are most welcome even if the “Barbadoes” version is somewhat curious in specifying brandy instead of the island’s signature rum.

Of the “Curious Drinks” some taste fine, if also curious indeed. The aptly named “Scorcher that combines the juice of half a lemon with cayenne in a glass of brandy is addictively puckerish, simultaneously hot, sour and sweet. The “Thunderclap” also earns its name with a equal parts brandy, gin and whisky, from the spelling presumably Scotch.

The “Texas Highball, essentially a Manhattan made with Bourbon and Port, is at least as appealing as the original iteration but then again, in the soft “Cocktail Section,” appears the “Saurkraut Juice Cocktail,” which speaks for itself. The three soft tomato cocktails in Good drinks, however, each would be excellent with the addition of a generous vodka jolt.

Altogether a strange and wondrous book, the kind of thing we should expect from the forgotten Heath, whom Jamie Oliver has called the best food writer of whom you never had heard, if in less grammatical terms.

Formulae for Heath’s “Tomato Cocktails,” fortified, however, with booze, appear in the practical.