We revisit a visionary socialist who brews beer in rural Massachusetts.

1. Something resembling a book report.

A curious book appeared in 2015. Its production values are poor; it looks, as its author notes with characteristic pungency, like a middle school social studies report. Its slight 176 pages are not written particularly well; sentences as bad as “False expectations won’t keep me from the happiness of another beer to love” and “The bright sunshine slants lower on the sky as the first calendar days of fall swing the northern hemisphere closer to the sun” should be forbidden from finding their way to print. The subject matter meanders, repetition recurs and the text displays no discernable structure.

Beer Terrain: From Field to Glass got nearly no notice on publication and, less than three years on, the sole copy in stock at Amazon has been discounted from an original price of $19 to $3. That is not necessarily a reflection on the quality of the book itself; its publisher in rural Hardwick, Massachusetts, is as obscure as its topic.

2. Smash the machines and stay at home.

Why, then, bother with a review? Notwithstanding its flaws, Beer Terrain is important in its idiosyncrasy, a sort of strangled manifesto for lost and against contemporary values. The author, Jonathan Cook, is an avowed Luddite and nothing if not contrarian. His book purports to be a travelogue but the disguise is thin. What concerns Cook instead is wresting agriculture in general and in particular all phases of production related to brewing beer back from big global business to local control.

In what should appear as his statement of purpose at the outset of the book, he waits until page 142 to applaud the kind of “preindustrial tradition” maintained by Trappist monks brewing beer in the unlikely locale of Spencer, Massachusetts.

Before a recent move to Worcester, Cook himself lived in West Brookfield, one of four contiguous towns bearing a common name (along with East, North and Brookfield unmodified) in central Massachusetts. Each of them is as beautiful as the next, their eighteenth century commons unspoilt by development or encroachment of any kind. That is important: An acute sense of place, a fierce pride in New England, permeates Cook’s outlook.

His vision is radical, uncompromising and somewhat perverse. It borrows, intentionally or not, from the nineteenth century British cooperative movement and is not only anticapitalist. Scale is everything, and it must be small: As the attentive reader will have discerned, the watchword is ‘local,’ and nobody adheres to localism like Cook.

3. Doing well by going green.

He justifiably admires the brewers, including Wormtown in Worcester and Throwback in North Hampton, New Hampshire, devoted to the green movement. Obsessed with minimizing their carbon footprint and benefiting their neighbors, they buy local ingredients whenever feasible and repurpose byproducts.

“Wormtown,” Cook explains, “gives its spent grain to a farmer for use as livestock feed. Turns out” a nearby trattoria

“purchases its pork from the same farm. Now they serve the beer to go with it. The cycle never leaves the area. A local farmer grows grain. A local maltster malts the grain. A local brewer makes the beer. A local farmer feeds his pig. And a local restaurant serves the pork paired with the beer that tied them all together.” (Cook 16)

An operative word in the description of this reactionary cycle is ‘gives.’ Profit is but the necessary evil that motivates local heroes to do good things; Wormtown does not even bother to sell the spent grain for a nominal fee. Elsewhere Throwback--its name must be beloved of Cook--does much the same thing. As its website urges customers: “Drink a beer, feed a pig.” They call one beer “Hog Happy Hefeweizen” in reference to the spent grain fed their pigs. (Cook 79)

Like any devout revolutionary, the ambition of his ideology is universalist, requiring adoption by everybody everywhere: “You know,” Cook righteously proclaims in his tortured prose, “we have made progress as a culture and, hopefully, as a species, when beer can be completely local and spread coast to coast at the same time.” (Cook 152) Once again his logic is unassailable.

4. The return of the native maltster.

After traveling through New England and the Hudson Valley to meet with hop and grain farmers, brewers and, signally, a maltster, Cook decided to start his own brewery. The maltster operates out of Hadley, another picturesque Massachusetts town in the Pioneer Valley. According to Cook, consolidation had winnowed the number of North American malt producers to two giants until 2010, when Valley Malt began malting grain grown by local farmers. (Cook 27) They since have been joined by Blue Ox out of Maine.

Without Valley Malt Cook could not have implemented his vision. He buys only malts from Valley and local hops. (Cook 152) He notes as a point of pride that “local malt costs two to tree times the price of the well-traveled stuff.” Make a little less profit, yes, and pay the farmer more while maintaining the virtuous cycle of local collaboration.

Another example; Cook appreciates the quality of the hop crop at Rock Island farm in Maine along with the fact that eager buyers across the country want, without success, to obtain some of the harvest. “It can’t happen,” he explains with approval, “because New England brewers buy all the local supply and will, for the foreseeable future, continue to keep it all to themselves.” (Cook 67, 68)

5. The home field.

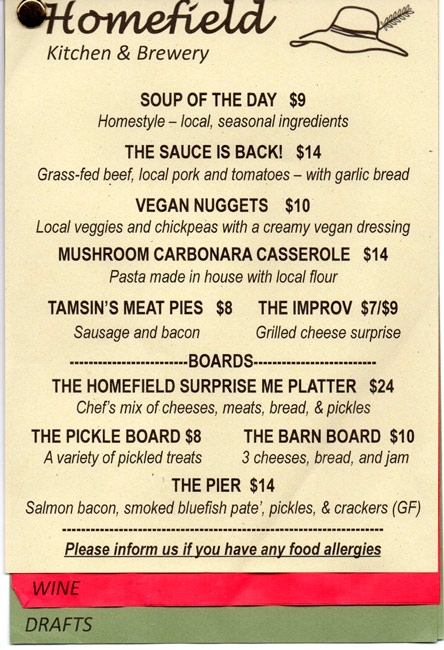

The Pioneer Valley in central Massachusetts has become a bit of a craft brewing capital. Brewers in addition to Wormtown include Hermit Thrush, Opa Opa (the proprietor has Greek ancestry), Strange (a name Cook could have appropriated) Wachusett, Wormtown and others including Tree House, which may be the hottest craft brand in the country. Cook operates the smallest and best of the lot. The name he chose for his Sturbridge brewery is an apt and clever triple entendre. Homefield refers to those Brookfields and nearby Brimfield. It also connotes his devotion to locale and to baseball, that most traditional of American sports.

The place is as idiosyncratic as its owner. Its purpose gets but second billing: The official name is “Homefield Kitchen and Brewery.” It inhabits the cellar of a junk shop whose jumbled pile of outdoor ‘antiques’ obscures a small Homefield sign. They have merchandise for sale, a little of it anyway. The effort is feeble and although the new hats do include “Homefield”, the original version did not even bear the brewer’s name. The hat did, however, depict a hat.

His wife and business partner along with their staff are friendly and affable while Cook himself can be by turns testy and personable. We like him. During one visit to Homefield the daily beer list included Sunsplash, described as “hoppy beer from here.” It was an outstanding version of a familiar traditional style, so we asked Cook why the list did not identify it as India Pale Ale. In response he snapped “I don’t know what that means,” and refused, without explanation, to consider the possibility that the beer was in fact an IPA.

If anything the beer, unpredictable as ever, is even better than before. Manifest, described only as “#167 ~ dark ~ 5%” is in fact a classic porter, perhaps the best we ever have drunk. Good Neighbor (“#170~hoppy bitter~8%;” yes, the spacing is different from no. 167) is even more appealing than what Cook calls it, a strong hazy New England expression of a peerless British style.

Homefield makes its own pickles now. The curried sauerkraut is an excellent standby; it was asparagus season when we visited early this summer so the spears were all over the menu, in a fish chowder, seared by themselves for service with “’daise” and pickled with a discreet dos of tarragon for the sour board that also included the kraut and some irresistible carrots pickled with coriander and ginger. Carrots ordinarily carry little appeal but these were addictive.

That was both disingenuous and consistent with his ideology. Disingenuous, because Cook knows how to brew and knows the process may be manipulated in countless ways to produce reliably consistent traditional styles. Beer Terrain itself discusses a number of New England IPAs and notes that “cask conditioned IPA” probably is his wife’s favorite style. (Cook 94)

6. The hobgoblin of unimaginative minds…

Cook had not been in the mood to elaborate, or perhaps thought our education was not worth his time. Had he been inclined to explain his thinking, Cook would have paraphrased another passage from his book.

“This beer,” he elaborates in describing “Local Harvest Ale” brewed in Maine by Sebago, “generically styled an ‘ale,’ is a one-of-a-kind original.” He considers it neither quite a brown ale nor an IPA. “Nor does the beer [sic] want to copy any other well-known style that was developed in a faraway place. It’s simply an expression of the regional terrain, impossible to recreate elsewhere, though good enough to make others want to try.” (Cook 67)

If his vision of terrior lacks a certain intellectual clarity, not least because different beers of the same style may and usually differ in taste, it is held honestly enough, and Cook takes it to the logical extreme. Inconsistency ordinarily is the hobgoblin of craft brewers fearful that customers would flee to a reliably recognizable product. Cook, however, considers it a cardinal virtue that local brewers ought to celebrate.

It is, in fact, his watchword: “There is a way to brand inconsistency. What the local fields offer is one-of-a-kind beers.” (Cook 152) As he elaborates a bit clumsily on his outlook elsewhere,

“ …. consistency of flavor is not the be-all, end-all many brewers think. Wine drinkers are prepared to have a favorite vintage of the exact same variety because they think of their drink as an agricultural product susceptible to seasonal influences. Couldn’t beer drinkers develop the same level of awareness?” (Cook 80)

Cook does not want to brew enough beer to bottle, and although he wants supply to drive demand, does not price his product at much of a premium. His drafts sell for eight dollars, high but not unfair by the standard of central Massachusetts, and sells local bottled “beer from friends” at a reasonable range of seven or eight bucks per pint.

7 … or not.

And unlike his beer, Cook conducts his business with consistency, keeping faith with his severe ideology. The kitchen at Homefield cooks with ingredients and serves food produced in Massachusetts; meat from Clover Springs Farm and Red River Farm in his hometown, vegetables from Still Life Farm in Hardwick (“our Winter CSA provider”), fermented foods from Hosta Hill in Housatonic, bread from a clutch of local bakers.

The Homefield cellar is a cozy place; structural flintstone, sturdy handsome tables and shelves built of wood. Paintings by local artists hang for sale along the walls. The bar alone separates a busy kitchen and the brewery from customers, an expression of the honesty that Cook espouses.

On weekends Cook hires local musicians to entertain. On Wednesdays and Saturdays the place evokes the happy chaos of a medieval market. and invites local artisans to invade his restaurant. They sell various wares; bread and other baked goods including British savory pies, honey from local hives, jewelry wrought by local smiths.

Any other owner, anyone with the merest adherence to capitalist doctrine, might see Homefield dangling from a rope of sand, but Cook has sustained the operation without compromising his principles for over two years now. Perhaps he is on to something. We only can hope as much and the signs are sound. At this writing Homefield is nearing its two hundredth batch of beer. People want what he has got and what he gives us.

Not so long ago the Pioneer Valley was an agricultural and culinary wasteland with the exception of a few legacy orchards that survived the destruction of its agricultural base after midcentury. The new network of farmers, suppliers and brewers has transformed the region in a manner unthinkable within the past decade. The scale is smaller than in the past; the big dairies, truck and tobacco farms are gone, but the quality of the products their smaller artisanal replacements now offer is unprecedented.

Homefield, the most radical of a pathbreaking bunch, could provide the template for a uniquely wonderful alternative economy.

Homefield Kitchen & Bar

3 Arnold Road

Sturbridge, Massachusetts

774.242.6365