Observations on the revival of British technique during the 1970s with; notes on the eighteenth century, an unfashionable dish of beef; and featuring a discussion of Clubland Cooking with some more notes, those about its author.

1. A forgotten artifact.

Clubland Cooking appeared in the most significant year of an auspicious decade for British cookbooks. At first glance the slim volume would not appear to belong in the company of gamechanging artifacts. Its subject, the cooking of exclusive London clubs, sounds arcane and unappealing in a time that celebrates the diverse and democratic.

Its author, Robin McDouall, was secretary, or major domo, of the Travellers, among the grandest of the grand clubs; a former Wing Commander in the RAF he would not, at least from a reading of his work, appear to fill any fashionable demographic. His recipes appear for the most part almost absurdly simple.

Unlike a number of its contemporaries, Clubland Cooking has not passed into the realm of minor legend. It does not appear even to have exerted any influence on the late twentieth century arc of British foodways.

Travellers Club

Other books from 1974 that did make an enormous impact include a timeless masterwork and a comprehensive survey. With English Food, Jane Grigson reimagined a traditional cuisine through her captivating prose and concise recipes. The long eighteenth century is a particular focus. For good reason; the Age of Enlightenment in Britain produced an array of intellectual luminaries and, in a considerably lesser but significant development, consolidated the unique foodways of the nation.

If Elisabeth Ayrton lacks the lyricism of Mrs. Grigson, the scope and rigor that characterize The Cookery of England remain unmatched. Not that her prose is pedestrian or that she did not unearth some striking stories from her sources. To introduce an extremely good early nineteenth century recipe for beef boiled with beer, by recounting the story from the North Country household where she found it

“that the dish had been prepared in the past by their parsimonious ancestors for the hay-making supper for tenants, because part of an old ox which had been kept to work all winter could be used, since the beer helped to tenderize the meat.”

In this case at least the stinginess was either overlooked or forgiven. “The tenants liked the taste of the beer,” descendants of the cheapskates told her, “and considered the dish a grand one.” (Ayrton 53)

In Norfolk to the southeast, James Woodforde did something similar, with a significant difference, for his parishioners during a different season a few years earlier. The minister was nothing if not generous, as Mrs. Grigson recounts:

“On Tithe Audit Day, in December, Parson Woodforde entertained the people who came to pay their dues, and softened the painfulness with plenty of drink. One year, twenty-two of them drank six bottles of rum, four bottles of port with plenty of strong beer,” which they polished off until the party ended around midnight.”

That, however, is hardly the point of similarity to the cheap Northern farmers. “Dinner was,” Mrs. Grigson explains about the Woodfordes’ house no matter who joined them at table, “as usual substantial on this occasion” and consisted of no less than seven dishes including “a boiled leg of mutton and caper sauce.” Woodforde, however, included the boiled meat because he liked it, not because it was cheap, as indicated by the presence of a roast sirloin of beef among those six other dishes. (Food with the Famous 54)

2. A living legend whose fame endured.

It took until the 1980s for the revival of British food to reach the restaurant, a development made possible during the previous decade, when some keepers of the flame set about reclaiming the national cuisine.

The most famous but perhaps least accomplished of them, Elizabeth David, was something of a pathfinder. She published Spices, Salt and Aromatics in the English Kitchen during 1970. The title is more than a bit of a misnomer. Compiled with dissonant formats and styles, the book is a pastiche of original essays along with older articles and afterthoughts. Many of them do not discuss spices, salt, aromatics or even the English kitchen.

The quality of the entries ranges from extremely good to decidedly dire. Many of the recipes lack attribution and better versions of them have appeared both before and after its publication.

The best, initial, chapters include learned incursions into the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, out to the Raj and irrelevantly but characteristically over to her only constant love, continental Europe.

Still, David did get things going, which after all should be her claim to remembrance more generally. Provocative but prone to acrimony in all things personal as well as professional, she became revered. David would be made a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature and receive an OBE.

She fired the British culinary imagination. More than any other author, she influenced the way the British thought about food for some three decades. The ordinarily acerbic Auberon Waugh maintained that “she… brought about a greater change in English life than any other woman” of the twentieth century. (Chaney xxi)

Harvard justifiably holds her papers based on the magnitude of her influence alone, in the collections of the Schlesinger Library on its Radcliffe campus. The library is a spectacular repository of culinary history, and Harvard should be commended for making its treasures available to the public.

Johnson & Wales in Providence, Rhode Island, is not so nice. The university that made its name as a cooking school barred the public from the museum housing its own considerable collection of culinary materials several years ago. Even before then, JW charged a fee to visitors. Now only affiliates gain entry.

Notwithstanding Spices, Salt and Aromatics, David may, in an ironic turn, have done more than any other figure to retard the rediscovery of British foodways in Britain itself. Robin McDouall wrote Clubland Cooking. Ordinarily adept at castigating unpleasant personalities (See, e.g., “Festive Miscellany” in the lyrical), he was an acolyte of David, among other things suspending disbelief at her exaltation of everything French over anything British, which extends even to misclassifying British dishes as French.

3. A detour toward Beef Wellington.

She once cooked dinner for McDouall to his uncharacteristically unconditional delight. That may entail his suspension of disbelief or perhaps of his critical faculties, for even among friends to the extent she had any, and they always, inevitably, fell out, David had a reputation as an indifferent cook. She served him Beef Wellington, which of course she called ‘Filet de Boeuf en Croute.’ In compliance with the New Fogey image he liked to cultivate, McDouall also likes to use French names for British dishes, a practice straight from the nineteenth century, in this case the incongruous ‘Filet de boeuf Wellington.’ The Iron Duke would not have been amused.

To be fair, David claimed the dish for France in French Country Cooking, although her version omits coating the beef with either foie gras or a lesser liver paste, which has become an integral element of the Wellington treatment along with her duxelles, before covering it with pastry.

McDouall claims to despise the preparation: “I think it is a gimmicky idea and I deplore clubs taking it up.” David’s simpler treatment was the sole exception to his rule. “The only time I have had it and enjoyed it,” he maintains in Clubland Cooking,

“was the first time I ever saw it--and that was dining with Elizabeth David. As one might suppose, it was delicious…. I usually discard the pastry. I didn’t discard hers.” (Clubland 81, 81n)

Another instance of unconditional admiration: “She says that, when cold, it makes an admirable picnic dish. I have never tried it but I believe whatever she says.” (Clubland 81)

Craig Claiborne at the New York Times.

In addition to the question of nationality, a certain amount of uncertainty shrouds the origin of this deeply unfashionable dish. “The history of Beef Wellington,” the Food Timeline goes so far as to say, “is a matter of historic contention.” (“Beef Wellington”)

Most commentators anchor the origin of Beef Wellington only to the twentieth century, and then to the United States. Glyn Lloyd-Hughes dates the earliest mention of something like the modern version to a 1939 guide to New York City restaurants and the earliest recipe to Craig Claiborne in his 1966 New York Times Cookbook. (Lloyd-Hughes 124)

The people at The Food Timeline, however, have found a simple variant--it coats the beef with “cold brown fine herb sauce”--in The Palmer House Cookbook from Chicago written by Ernest Amiet and published in 1940. They found another, more complicated recipe attributed to the Palmer House from 1958: James Beard, one of the most noteworthy (and Anglophile) of American food writers, in his Selection of Famous Hilton Recipes. That one coats the beef with a recognizably Wellingtonian paste made from chopped “York ham” (where in the United States did he find it?), minced mushrooms, parsley, shallot and “rich Madeira sauce.” (Food Timeline)

Theodora FitzGibbon includes variations on Beef Wellington in both Irish Traditional Food and A Taste of Ireland, both published too late to compete in the inventors’ sweepstakes, but oddly enough omits the dish from her Art of British Cooking. The recipe from the first book includes mushrooms but not the liver paste; the recipe from the second encases the beef alone in its pastry. She prefers the name Wellington Steak or, the Gaelic, Steig Wellington, noting without more about its provenance that the preparation “was said to be a favourite of the duke of Wellington, who was born in Ireland and it is sometimes known as Beef Wellington.” (Irish Traditional Food 104)

From that, and that alone, Claiborne was “persuaded that beef Wellington is a dish of Irish origin.” (Food Timeline) The proposition is more than dubious. Inclusion of a recipe by Mrs. FitzGibbon in her Irish cookbooks does indicate that the dish was cooked in Ireland but does not necessarily mean it originated there.

Although he did become an advocate of catholic emancipation, Wellington was no champion of Ireland and, notwithstanding his birthplace, did not consider himself Irish. Nor did Irish reformers and republicans. Daniel O’Connell famously mocked him during one of his Monster Meetings with an aphorism ordinarily misattributed to the duke himself: “To be sure he was born in Ireland, but being born in a stable does not make a man a horse.” (“most famous thing”)

It is most unlikely that the horseman in question would have chosen to be identified with anything of Irish origin.

As the result of some typically rigorous research, the estimable Jane Grigson deviates from the other sources about the first description of Beef Wellington. Parson Woodforde, observant diner and indefatigable diarist, describes the duke’s dish, if not by name, as “Beef-stake tarts in turrets of paste” in one of his prolific diary entries, from 1791. In the hands of Mrs. Grigson the turrets contain the slather of “a moist puree” of minced mushroom and onion fried in butter, omitting, like David and the Palmer House, the foie gras, which apparently represents the innovation that earned the traditional dish its ducal pedigree. (Food with the Famous 52)

4. Further jottings about James Woodforde…

Mrs. Grigson likes the parson for more than his turrets. Woodforde has been attacked with some anachronism as, in the words of Mrs. Grigson, “a sad glutton, greedy and gouty from over-indulgence.” She will not partake of the conventional wisdom, which springs in part from the sloth of other readers.

The parson did record everything he ate, and the standard single volume abridgement of his diaries encourages the misperception because it emphasizes eating. A five volume set, edited by John Beresford and published in series starting in 1926, reveals its author’s “skill and delight, rather than piggery.” (Food with the Famous 43) Not, however, all his skill or delight; the Beresford edition itself is an abridgement of Woodforde’s “sixty-eight little black-bound notebooks.” (Hughes xvii, xvi)

The equally estimable David Hughes echoes Mrs. Grigson. The Parson Woodforde Society considers his abridgement, from 1992, “better edited than the Beresford edition” and “probably the best one-volume introduction to Woodforde.” Hughes joins her in deriding the conventional attitude toward Woodforde, “immense quantities of food being in the mistaken view of most commentary about the parson the crux of his existence…. ” (Hughes ix)

Virginia Woolf may not have fallen for the trope of gluttony but she dismisses the man as a bore. “His diary,” she thought, “is the only mystery about him.” (quoted at Hughes x)

Hughes parsed the diary with greater care. He finds the character who emerges from the journals irresistible, paradoxically both straightforward and complicated while also oblivious to the internal tension:

“There is no cheating in Woodforde, no posturing; he lives with a guarded honesty in his sphere of prose. His faith in the eternal life is not only absolute but humorous; at a further level it is possibly non-existent. He never noticed his contradictions.”

The contradictions did not arise out of hypocrisy and less from distraction than from a stubborn generosity of mind. His servants were an ongoing source of anxiety and anguish but he could not bring himself to behave toward them as badly as they behaved more generally, an implicit indication of Woodforde’s humanity.

One of them, twenty five year old Bill, announced his determination to leave service for the navy. In response Woodforde lamented in his journal that when he “goes away I shall have no one to converse with--quite without a friend.” (Hughes 170)

Eight days later, events had taken a different turn. Woodforde found it necessary, after buying Bill dinner, to question him

“a good deal in the evening at the Angel about his being great with my Maid Sukey, and he confessed… that he had been great with her 3 or 4 times…. Sukey had admitted that [a Harry] Humphrey was great with her… Bill certainly had Sukey first---- .” (Hughes 171)

Two days later a neighbor called on the parson, who had “a long Chat with him about Sukey, also about the Highways & lastly about Methodists.” (Hughes 175)

These references to subjects other than Sukey are not so banal as a modern reader might think. At the time highways represented a relatively new improvement that revolutionized not only transportation but also communication and literature; Methodists, a relatively newfound threat to the authority of his own, state sponsored, sect.

A month later: “This morning I had some suspicion that Bill was concerned with my Maid Nanny and also that she appeared to me to be with child.”

Within two weeks Bill had confessed to contracting a venereal disease in Norwich, the closest city to the parsonage. “He is,” Woodforde had reversed himself to conclude, “the Occasion of nothing but troublesomeness to me. I will therefore get rid of him as soon as I can.” (Hughes 175)

Six days later Woodforde told Bill “that I should have nothing more to say to him, or do for him”--and promptly broke his word. (Hughes 175-76) Even after all the trouble the servant had caused him, Woodforde would not allow himself the luxury of vengeance, let alone acrimony. He gave Bill the savings he had held for him, and loaned him a horse to go and seek the advice of a doctor.

That same day Woodforde gave money “To a poor Norwich Weaver in distress,” refused immediate payment from a neighboring woman for ten of his geese and “Privately named a base born child of my late Maid’s Sukey…. ” That evening he invited another neighbor to dinner, “his wife being from home.” (Hughes 176)

Parson Woodforde

Granted Woodforde was a churchman, but churchmen can be as cruel or capricious as anyone else and these acts of grace transcend the obligations of his position.

All this despite a series of tribulations that should have tried the parson’s faith. A ring of burglers robbed his stable; rather than bemoaning misfortune he notes that neighbors had also been robbed. Woodforde suffered that and other misfortunes, often recorded with candid if inadvertent good humor: One day a clumsy man

“drew my Tooth but shockingly bad indeed, he broke away a great Piece of my Gum & broke one of the Fangs of the Tooth it gave me exquisite pain…. ”

That night the pain continued and things got worse, at least in terms of indignity:

“Very much disturbed in the Night by our Dog which was kept within doors to night, was obliged to get out of bed naked, twice or thrice to make him quiet, had him into my room and there he emptied himself all over the Room…. ” (Hughes 148)

The authorial honesty and lack of self-consciousness of passages like these make his diaries an invaluable artifact:

“With daily truth he stated his life as it came. His close-written pages profess no trace of ulterior motive. He never knew whether he was being interesting or a bore…. Without artifice or reflection Woodforde held up the looking-glass of his journal to offer, to a posterity he never considered, a reliable, impartial, altruistic image of one of the more mysterious periods in relatively recent history.” (Hughes xiii)

“No amount of history written with hindsight,” Hughes sensibly insists, “can be anything like as good as a document never meant to be read.” (Hughes xvi)

Stolid paradigm of the rural gentry that he was, the parson declined to aspire to airs or pretense even though he dined with luminaries, including “his grand neighbor, Charles Townshend, MP for Yarmouth.” (Food with the Famous 52)

Woodforde and his wife worked their farm themselves,

“without the housekeeper and head gardener of the country house…. James Woodforde was sometimes caught by early visitors, still in his cotton nightshirt, working among the artichokes and cauliflowers and cucumbers.” (Food with the Famous 43)

Those and his other crops were a source of quiet pride for the parson:

“He notes with happy modesty that he has given fruit and vegetables to his neighbors for their dinner parties, or that they had had a successful party at his house.” (Food with the Famous 44)

Woodforde was an acute observer who found delight in the everyday--and in the unexpected irruptions of living on the land. When,” as Mrs. Grigson notes, there was anything to see, “he was there to see it.”

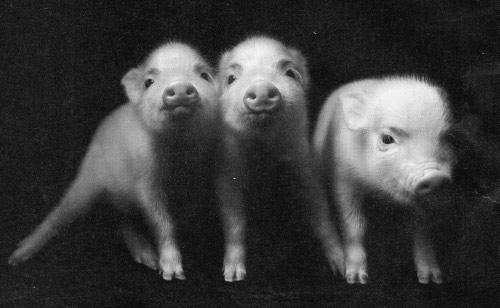

And so to several days with the parson’s pigs, an apparently mischievous pair:

“Brewed a vessel of strong beer today. My two large pigs, by drinking some beer grounds taken out of one of my barrels today, got so amazingly drunk by it, that they were not able to stand and appeared like dead things almost, and so remained all night from dinner time today. I never saw pigs so drunk in my life, I slit their ears for them without feeling.”

The following morning saw some improvement; not much. “My two pigs are still unable to walk yet, but they are better than they were yesterday. They tumble about the yard and can by no means stand at all steady yet.” But then the buzz abated: “In the afternoon my two pigs were tolerably sober.” (Food with the Famous 43-44)

Reciprocal hospitality was, it is true, as important to the English gentry as it was to their more celebrated Ascendancy roisterers across the Irish Sea, but even so it is not difficult to deduce why Woodforde in particular got so many invitations. It appears from his diaries that the parson was a particularly convivial companion who delighted in company and conversation. He therefore “viewed dinner,” not merely as an opportunity to eat good food, “as no mere punctuation, but the social high point of the day, and thus worthy of honourable record.” (Hughes xv) The high point of 2 July 1784 was not atypical. He, his wife and seven other companions were the dinner guests of a Mr. Smith. They dined on

“boiled Beef, rost and boiled Chicken, part of a fine ham, a couple of Ducks rosted and Peas--Pudding, Tarts and Cheese-cakes. For supper a cold Collation, with Lamb-Stakes and Gooseberry Cream and green Peas &c.”

Despite all the dishes and second supper the Smith household was no temple to gluttony. Instead of eating a series of courses, guests passed platters to choose varying amounts of anything they liked in the eighteenth century manner, and the occasion was not limited to dinner as we know it now. “We were very merry the whole day and night,” explains Woodforde, and only “broke up at 4 in the morning…. Got home about 5 o’clock… Saw the Sun rise coming home.”

Ever thoughtful of the servants, Woodforde remembered to tip “Mr. Smith’s Boy--Robin.” (Hughes 235)

So dinner was more a late lunch, supper more a late light dinner for happy company. It was not an uncommon atmosphere: “Parson Woodforde laughed so much” on another evening “that he choked on hot gooseberry pie.” (Food with the Famous 45)

5. …and the eighteenth century society in which he lived.

Woodforde may have been a minister but seldom trod the straight and narrow. Hughes submits among other evidence of his subversive side “the tubs of gin and rum deposited at regular intervals on his doorstep by smugglers.” (Hughes xv) In that and other ways Woodforde personifies the comparatively tolerant social structure of eighteenth century Britain, a structure remarkably fluid for a European society of its time, “typifying England in his own clerical way.” (Hughes xiii)

His relationship to Townshend, the friendship between minor gentry and a great lord, does not appear to have involved much deference on the part of the parson. The diaries indicate that Townshend called on Woodforde, and Woodforde on Townshend. Their reciprocity says as much about Townshend’s lack of pretense as it does about the parson’s personable nature.

Much like the fictive characters of Jane Austin, the tumults of the time attract nearly none of Woodforde’s attention: “He hardly noticed--or only just--the more potent of events, an attempt on the king’s life, a mobilisation in Norwich, a war in America. Yet up there in the flats of Norfolk he lived through the French Revolution.” (Hughes xii)

As Hughes observes, the parson inhabited “ ….a country reveling in freedom. Except in times of national emergency,” and sometimes and always to some extent even then, “you could say more or less what you liked, you could read in the press to your heart’s content all sorts of libel of the high and mighty, you could go wherever you wished without question. Here,” for the prosperous members of the political nation at least, “was a version of Utopia. All Europe gaped in envy at the stability of life across the Channel.”

King’s Chapel

“James Woodforde,” Hughes continues, “shared these qualities of thought, word and deed even if he seems to allow the comforts of life to take precedence over the intellect.” (Hughes xiv) Then again Woodforde was hardly insensate in matters aesthetic. He traveled to Cambridge, for example, “and saw King’s Chapel the finest I ever saw, all of it carved Stone the Roof the same--most capital piece of Architecture indeed.” Then, another instance of generosity, he “Gave a Man that shewed it to us 0.1.0.” (Hughes 146)

Woodforde’s preference for the quotidian, however, is what renders his journals so invaluable a resource for understanding the common contours of the age, of the lives most people in his milieu lived.

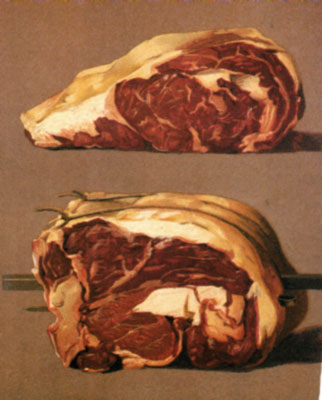

6. The rost beef of old England.

In a most improbable quirk of historiographical fate, the last words Woodforde wrote were “Dinner to day, Rost Beef &c.” (Hughes vii, 433) On any number of counts, roast beef among them, McDouall distinguishes the club from household kitchen:

“Clubs are not much of a guide, as far as roast beef is concerned, to the private housekeeper. A huge joint, however tender and pink, is not very appropriate to a private house, unless you happen to live in Blenheim and have a couple of dozen grandchildren.”

Then, in characteristically contrarian mode, McDouall proceeds to provide a recipe. Other than that, the Wellington he claims to avoid “in Chelsea bistros (or should one say bistri ?)” is the only one for preparing beef in the book. McDouall selects fillet of beef (filet mignon to Americans) and likes to paint it with butter and peanut oil which, perversely, he calls “arachide,” the botanical term for the peanut but not its oil. A little more misdirection follows in the explanation of his preference for saucing the roast:

“I like horseradish sauce with it. If you have a garden, grow it, grate it and mix it with double [heavy] cream. Having no garden, I buy it in a bottle--plain horseradish, not horseradish sauce--and mix that with cream.” (Clubland 80)

McDouall also likes bread sauce, essential for roast chicken but not for beef. “I hate,” he notes, “cloves in most things and think they ruin bread sauce.” (Clubland 103) If the point of roast chicken is bread sauce (and it is) then you could do worse than take his advice. The recipe, which appears in the practical, is unusual in chopping the onion instead of merely infusing the sauce with a whole one pierced by the forbidden clove and, therefore, unusually good.

7. Resentment of the Reform and its erstwhile chef.

In a break from his usual minimalism, McDouall reproduces the elaborate formulae for both Mutton (or lamb) Cutlets Reform and their sauce from Soyer’s 1846 Gastronomic Regenerator because, he repeatedly complains in a running skirmish throughout Clubland, “the Reform Club… declined to give me any recipes.” (Clubland 97)

The Reform Club

Soyer is a colorful and controversial character, both loathed and beloved in his time and to posterity. He was loathed for his self promotion--one commentator considers him, anachronistically ‘the first celebrity chef’ while McDouall, hardly reticent himself, finds him “publicity mad” and suspects “that his capacity for personal public relations was greater than his talent as a chef” (Clubland 54, 12)--, his limited success in improving the conditions endured by British soldiers in the Crimean War, inadequate effort to meliorate the Irish famine, contrived literary conceits (including, according to McDouall, a cookbook that “takes the form of a nauseating correspondence between two women friends, Hortense and Eloise”) (Clubland 47) and fussy food.

Conversely, Soyer was beloved for his flamboyance, his work with Florence Nightingale to improve the conditions endured by British soldiers in the Crimean War, Irish famine relief, imaginative writing and innovative cooking.

Soyer’s recipe for reform sauce specifies nineteen ingredients, a number of them requiring prior cooking processes, and eight different procedures on the stovetop. McDouall quotes it in full and then cracks the whip: “Much ado about nothing, in my opinion.” (Clubland 98)

McDouall wonders whether Hortense’s “Anti-Cholera Diet… was responsible for some of the casualties in the Crimean War”… but then immediately admits to admire aspects of ‘her’ book: “Here, however, are some rather good egg dishes.” (Clubland 47) They also appear in the practical.

8. A meticulous minimalist…

Sauces, however good except possibly Soyer’s, are not the focus of Clubland Cooking, and the apparently absurd simplicity of his dishes in fact serves McDouall well. If David was inconstant and uneven about British food, McDouall displays a consistent and persistent approach to its preparation. A dedicated minimalist, he repeatedly reduces his recipes to bedrock essentials. Whether or not another cook agrees with that approach, it describes a discernable, fastidious style of comfort food that is reasonably easy to cook and, McDouall convinces his reader, encapsulates the clubland cooking of his and its previous eras.

Most recipes require but a few ingredients: Pork chops with mustard: six, including the mustard and a spoonful of vinegar; sardine pate: three; “Potted shrimps: the shrimp, their butter (“unsalted”) then mustard, nutmeg and pepper; grilled Dover sole: also three.

His recipe for cottage pie (seven ingredients including the Worcestershire and potato topping) epitomizes the fastidious simplicity:

“Chop (rather than mince) the beef…. Don’t put in all the liquid if it is too runny…. A posher cottage pie can be made with the remains of roast turkey, pheasant or chicken. But the beef cottage pie is infinitely better made with raw meat than with ‘remains’.” (Clubland 99-100)

Oddly enough despite those variations, shepherds’ pie, the iconic original based on lamb, would not appear to inhabit clubland, or at least Clubland.

Orange can pair compatibly with duck. Rather than resort to the traditional treacly Sauce a l’Orange, McDouall infuses his stuffing (all of nine ingredients including butter and herbs) with orange zest, a minor masterstroke that made us feel foolish for its omission from our own duck forcemeat over all these years.

Even something as simple as potted ham gets close attention from McDouall. The ingredients are prototypically primordial but he takes the extra step of marrying them in the oven with a bain marie. (Clubland 43)

Or you can make your own.

Or you can make your own.

9. who (sometimes) celebrates, or celebrates with, the sumptuous.

If, however, McDouall relished the simplicities he thought defined British food he by no means disavowed French cuisine so long as it remained confined to its proper purpose. British cooking was for fellowship; French food for display.

“From the earliest days of clubs, food seems to have developed on two lines: first, there is the very simple food of the chop-house: the chop, the steak, the sandwich, the savoury. Then, for private parties, there have always been the sumptuous meals, cooked by a French chef in the French style. The resulting evolution is that today club members like home cooking--call it, perhaps, country house cooking, with a strong emphasis on what I can best describe as nursery food.”

The French line does not embrace the rural and Mediterranean ‘peasant’ styles promoted by David but rather the rich, lavishly sauced northern cuisine of the metropolis reinterpreted for British taste. “When occasion demands,” McDouall explains with an inferential critique of the richness itself,

“the chef must abandon the curried chicken, the apple tart and the ground rice pudding and produce lobster Thermidor, tournedos Rossini and Nesselrode pudding--not all, I hope, at the same meal.” (Clubland 18)

10. Back to basics.

French food, however fabulous for feasting, is not the focus of Clubland because the great majority of dishes to emerge from its kitchens are British. Despite the tease in his introduction, McDouall includes no recipe for lobster Thermidor, no tournedos Rossini, no Nesselrode pudding. In that he deserves celebration along with the Ayrtons, Davids and Grigsons, if not as a rescue archaeologist then as a stout keeper of the flame.

Recipes from Clubland Cooking appear in the practical.

Sources:

Anon., The Food Timeline: “Beef Wellington,” www.foodtimeline.org/foodmeats.html#beefwellington (accessed 30 December 2019)

Anon., “The most famous thing O’Connell said… and Wellington didn’t,” Irish Philosophy, www.irishphilosphy.com/2018/08/06/oconnell-wellington/ (accessed 7 January 2020)

Elisabeth Ayrton, The Cookery of England (London 1974)

Theodora FitzGibbon, The Art of British Cooking (London 1965)

Irish Traditional Food (New York 1983)

A Taste of Ireland (Boston 1969)

Lisa Chaney, Elizabeth David: A Biography (London 1999)

Jane Grigson, English Food (London 1974)

Food with the Famous (London 1979)

David Hughes (ed. and “Introduction”), James Woodforde, The Diary of a Country Parson (London [Folio Society] 1992)

Glyn Lloyd-Hughes, The Foods of England (Adlington, Lancs 2010)

Robin McDouall, Clubland Cooking (London 1974)