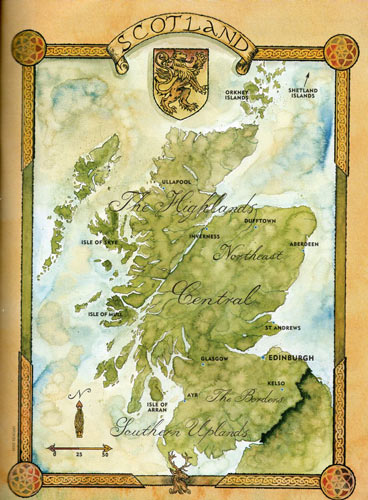

A tale of two Scottish cities.

Two cookbooks appeared within two years in Scotland; one in Edinburgh, the other in Dundee. The first, Edinburgh, publication from 1827 is a literary and comedic showstopper as well as exemplary set of instructions. Those to make powsowdie represent, as the great Jane Grigson has noted, “the recipe in its perfection” and it is not alone. (Grigson 160) Against odds, The Cook and Housewife’s Manual written by Christian Isobel Johnstone under the pseudonym Meg Dods, ‘herself’ the character in a novel by Johnstone’s friend Sir Walter Scott, has attracted a dedicated retinue of followers including Scott himself, Peter Brears and Alan Davidson in addition to Mrs. Grigson.

Her contemporaries described Johnstone “as extremely retiring, amiable, and accomplished, and ever ready to befriend young authors.” Thomas De Quincey considered her a genius who practiced “the profession of authorship with absolutely no sacrifice or loss of feminine dignity” (Goodwin), a jarring enough description today but the highest praise in its time.

People liked her, and no wonder. She was generous enough with her time and money to promote and support younger authors of either sex. Self-effacing to a fault,

“she shrank from anything like publicity or conspicuousness…. Even the good she did was often concealed from those for whom it was done. Many persons came to occupy respectable positions in the world who were indebted exclusively to her plans, devised without solicitation, and untold when they were successful.” (Conolly 245)

Catherine Dalgairns compiled the other book, The Practice of Cookery Adapted to the Business of Everyday Life , a stylistically unornamented repository of more than 1400 reliable recipes that garnered generally favorable notices upon publication in 1829. Mrs Dalgairns was not the public intellectual Johnstone would be considered today but The Practice of Cookery sold well and enjoyed a number of evolving editions until 1861. Eventually however the book drifted into obscurity, a neglect Mary F. Williamson intends to rectify with Mrs Dalgairns’ Kitchen: Rediscovering “The Practice of Cookery. ” If not a scholarly number it embodies a worthy enough cause, highlighting an overlooked classic that should appeal to the general reader and so should the selection from the book of original recipes modified by Elizabeth Baird for cooking in twenty-first century kitchens.

1. The process of early publication.

Williamson provides a sound description of the early nineteenth century Anglophone kitchen and its implements before reproducing the text itself, unfortunately altering the original spellings in conformity with twenty-first century norms, another apparent attempt to entice the general reader.

In a long, uneven introduction--her own 2007 essay for the Bibliographical Society of Canada covering much the same ground is better--Williamson traces the history of its drafting and publication. “The saga,” as she asserts, “sheds invaluable light on the highly personal and flexible world of early nineteenth-century publishing in Britain.” (Williamson xxi) Mrs Dalgairns fell out with John Murray of London, her first publisher, in much the same way as Maria Rundell before her. Murray however had published A New System of Domestic Cookery , while Mrs Dalgairns would turn to Robert Cadell of Dundee, the second publisher of Sir Walter Scott.

Basil Hall, an English adventurer and occasional author, knew both Mrs Dalgairns (Williamson speculates without evidence that they shared some sort of unspecified romantic connection before her marriage) and Cadell. Williamson believes that Cadell would not have purchased the book without Hall’s intervention although, again, the case is thin. If true, his involvement would say something about the difficulties that could beset women authors of the era.

Williamson is a lifelong advocate for historical Canadian cooking, an unjustly underreported topic. She discovered some years ago that Mrs Dalgairns was born on Prince Edward Island and lived there for twenty-two years before emigrating with her Scots husband to Britain in flight from his increasingly agitated creditors. Following another string of financial failures, this time in London, they wound up in Dundee where another series of bankruptcies ensued. Notwithstanding her early years in North America, The Practice of Cookery was published there and always has been considered a Scots cookbook.

Much like Hannah Glasse or Elizabeth Raffald, straitened circumstance likely motivated Mrs Dalgairns to embark on the book. She was not a professional cook or culinary instructor but in contradistinction to France or Italy both England and Scotland by then shared a robust tradition of women, including amateur women, who wrote cookery and household manuals.

Williamson speculates that the peoples who have populated PEI as its history unfolds inform the work of Mrs Dalgairns to argue that her recipes

“were drawn from a wider sphere of international cookery than is found in the cookbooks of her English-speaking contemporaries”; “only Catherine Dalgairns brought to her successful authorship a diverse background, having experienced a wide variety of culinary traditions.” (Williamson lxxx; xx)

Among them Williamson includes “Mi’kmaq, Acadian, Scottish, and, to a lesser extent, English” as well as American, French, Irish and Raj influences. (Williamson xx) It is a dubious claim. Mrs Dalgairns was born in 1788 and left Prince Edward Island during 1810, while the British had deported the majority of Acadians during the Seven Years’ War beginning in 1755.

3. The case for France and for a First Nation.

As Peter Brears has demonstrated, the culinary myth of an early French connection gets scant support from the historical record. It is important for any understanding of Scots cuisine, he writes of the eighteenth century in particular, to “debunk the Auld alliance as a culinary influence.” (Brears xxi-ii)

“If we look for real evidence for the origins of gentry cookery in Scotland,” Brears adds,

“we must discover which books were being bought and read by its ladies. They were neither Scots nor French, but English, as we can see from manuscript accounts.” (Brears xxii)

None of this may please Scots nationalists, and Brears may understate the significance of indigenous creations and adaptions to the evolution of a national cuisine, but it does appear decisively to eliminate the influence of France.

“Looking through the index and pages of The Practice of Cookery ,” Williamson maintains, “the reader may be struck by a surprising number of recipe titles suggesting a French style of cooking, such as à la Crême, or à la Turque, à la Hollandaise… and so forth.” Those titles do no such thing, however, but rather give French names to a dish bathed in cream, another in the style of Turkey and a third that is Dutch.

Then, in the next sentence, Williamson weirdly undercuts her point by observing just that: “Many recipes simply bear French names…. ” “To assume that recipes not bearing French names are not French,” she later adds in an incomprehensible passage, “is to ignore the influence of French culinary terminology on English, Scottish, and even Canadian and American recipe names, together with cookery methodology that can be traced back to Medieval times.” (Williamson l) None of this gives the reader confidence in the continuing contention that The Practice of Cookery draws from ‘multicultural’ sources, and neither do contemporaneous accounts of Prince Edward Island.

In 1818 a writer called John Cambridge described, among other things about PEI, its inhabitants. They

“consisted chiefly of emigrants from England, Ireland and Scotland, the States of America, and a few from Germany. There are also about six or seven hundred of the original Acadian French settlers, who occupy three villages, and live comfortably by farming and fishing.” (Cambridge 6-7)

Cambridge makes no mention of Mi’kmaq or French inhabitants, nor of contact with the other islanders by those few Acadians living apart. And as Williamson herself concedes, “it is impossible to know whether the presence of the Mi’kmaq people… exerted an Indigenous influence on food choices and cooking.” (Williamson xvliii) It therefore appears that at least some of the peoples who Williamson claims contributed a uniquely multicultural cast to The Practice of Cookery either had left PEI before the author’s birth or had not yet arrived before her departure.

4. The (at times reluctant) case for Scotland.

And the population that did live on the island when Mrs Dalgairns was there may have been predominantly Scottish; much of the immigration Cambridge describes may have occurred later. Williamson again, discussing the years immediately following the end of the Seven Years’ War:

“From the outset, immigration from Britain was dominated by Gaelic-speaking Scots Highlanders” and “Scottish Islanders” although she provides no citation for the assertion. (Williamson xvii)

Mrs Dalgairns did draw on Scottish sources whether or not she explicitly identified her recipes as such. Williamson notes, a lovely detail, that “Anna Prophet’s Oxtail Soup” is named for her because she was the Dalgairns’ resident cook in Dundee, a fact that casts some doubt on Williamson’s conviction that Mrs Dalgairns tested recipes herself. (Williamson xiii)

Hers is a characteristically British cookbook of its time, and the recipes themselves reflect the conclusion that the culinary influences on Mrs Dalgairns were the same as those of her contemporaries. None of the recipes in her compilation displays anything unique to Acadian or Mi’kmaq cooking. She does not infuse a fricot with herbes salées or bake cipaille, rappie pie or tourtière; simmers no chaud nor poutines blanches; fashions no nun’s farts or holes, no ploys nor pot en pot. It is not for nothing that, as Williamson herself notes, “ ….reviewers of The Practice of Cookery seem not to have picked up on the wide-ranging geographical and ethnic sources of her recipes.” (Williamson xlv)

Most other British cookbooks of the period, including The Cook and Housewife’s Manual , also are replete with dishes described as originating variously in the Netherlands, France, India, Spain, sometimes Turkey and other ‘exotic’ locations whether or not they actually arose there, and whether or not their authors had actual contact with those sources. The phenomenon was more a manifestation of marketing, less of true transnationalism. It is after all more a question of what you know than where you live that determines what you write, and as the anonymous author of a Dalgairns profile online observes, she was “very much a child of the British Empire” whose “Canadian association is tenuous… and mostly an accident of birth” rather than someone with “[t]he strong ‘Canadian’ connection” that Williamson would claim for her. ( Cook’s Info ; Williamson lxxix; quotation of ‘Canadian’ in original)

At one point Williamson also appears to consider The Practice of Cookery a cosmopolitan artifact of Scotland; at another she insists it is no such thing, but those contemporaneous reviewers disagreed. One of the most cited English assessments, which Williamson would debunk on the basis that Mrs Dalgairns spent only a few years in Dundee before her death, complains that she “exhibits too palpable an addiction to Scotch dishes. This is a prevailing peccadillo--if not the heinous fault of all Picts, old or young, male or female.” ( quoted at Williamson xxxviii; Cook’s Info ) Whether or not the daughter of empire was predominantly a product of Scottish culture, she wrote like a Scot.

6. A new audience… or not.

According to Williamson, its focus on “the mistress of a family,” on the housewife rather than her servants, also sets The Practice of Cookery apart, another dubious claim. To cite but one example, the title Johnstone chose for her book explicitly refers to ‘the housewife’ as well as cook. At the time, as Williamson infers, the same woman might perform both duties in her household.

Nor is it clear that housewives in fact were the sole or even primary intended audience for the The Practice of Cookery . Mrs Dalgairns also aimed it at “any cook or housekeeper of limited experience.” As a London reviewer declared: “The wisest man… will recommend to his housekeeper’s notice Mrs Dalgairns’ ‘Practice of Cookery.’” ( Cook’s Info 3) The Gentleman’s Magazine also considered it a guide for hired cooks as well as housewives: “It is a valuable present for Cooks, or for young mistresses of families, where economy in domestic arrangements is necessary.” (Williamson xxxvii) Williamson unwittingly makes the point by quoting both reviews.

7. An unadorned artifact.

Unlike Johnstone, Mrs Dalgairns is by no means inventive in terms of writing style, culinary art or range; one reviewer describes her as a “respected editress” rather than author. Mrs Dalgairns herself touted the fact that none of the recipes in The Practice of Cookery is new. Instead, she promoted the book with the claim that she or acquaintances had simplified and improved existing instructions, in the minds of her audience and a number of reviewers much the same thing. “An original book of cookery,” she reasoned, “would neither meet with, nor deserve, much attention; because what is intended in this matter is not receipts for new dishes but clear instructions to how to make those already established in public favour.” ( Cook’s Info 8)

One reviewer quoted that passage with approval, to concur that her “reasoning is very just, for none but the most thankless of gourmands … would sit down and weep for new worlds of luxury.” ( quoted at Cook’s Info 8) Except, of course, that we did and we do. Still, those appraisals are accurate enough, and fair as far as they go. They also render The Practice of Cookery less interesting as a cultural marker than original efforts from the likes of Johnstone or Dr Kitchiner.

The distinction was not lost on contemporaries. Williamson quotes the Scots Times :

“Her volume does not contain the poetry of cookery, like Kitchener’s [ sic ] Oracle nor does it sparkle with the literature of the culinary art, like the manual of our friend of the Cleikum Inn [Meg Dods]…. ” ( quoted at Williamson xxxvi-vii)

8. The voice of an author.

Williamson treads firmer ground in assessing the tone of the text and in particular the “Preparatory Remarks” beginning each chapter. It does, as she contends, disclose a discernable personality. It is brisk and businesslike, uninhibited about dispensing advice, some of it inevitably misplaced (this was 1829), some of it unimpeachably sound:

“Vegetables are always best when newly gathered, and should be brought in from the garden early in the morning; they will then have a fragrant freshness, which they lose by keeping.” (Williamson 168)

On the universally tricky process of producing pastry:

“Puff paste, if good, will rise into blisters in the course of rolling it out; it may be made with three quarters of a pound of butter to one of flour; the flour should be dried, and is the better for being sifted.” (Williamson 185)

On the timeless and fickle nature of the egg:

“If in breaking eggs, a bad one should accidentally drop into the basin amongst the rest, the whole will be spoiled; and therefore they should be broken one by one into a teacup.” (Williamson 183)

British empiricism informs The Practice of Cookery , and in a way most helpful to the cook. In an era before the invention of the thermostat, perform a test:

“To ascertain if the oven be of a proper heat, a little bit of paste may be baked in it, before anything else be put in.” (Williamson 184)

And so forth throughout.

The Practice of Cookery is, as its reviewers observed, utilitarian. Absent are the madcap asides, self mockery and long digressions that render ‘Dods’ delightful. She is a Persian rug to Mrs Dalgairns’ linoleum sheeting.

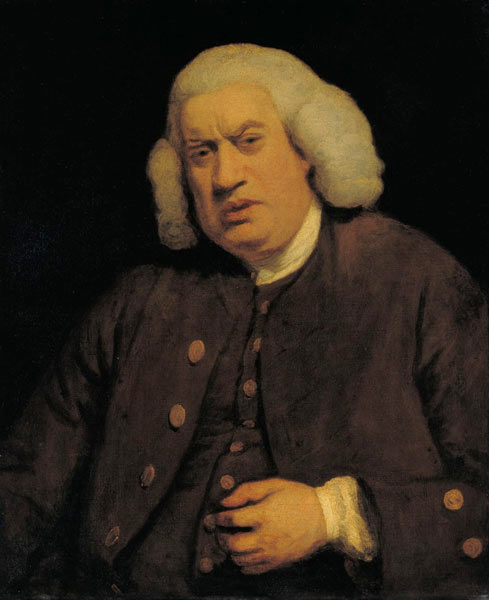

Meg Dods

Meg Dods

9. A dazzling feat.

The Manual injects cultural and social satire of a high order within and around its recipes, at once idiosyncratic and inimitable. Its introduction and a number of the footnotes that amount to a joke running though the book together mark it as one of the most imaginative, and funniest, works in any genre to address issues of national identity and the emergent cult of politeness, as well as self-interested hypocrisy, not least as practiced by moralizing reformers and representatives of organized religion.

The witless members of the Cleikum Club, a fictional gathering of self-styled gourmands, are vehicles for much of the commentary, but a reader also hears the voice of Johnstone herself.

To cite a single topic, she considers the poor particular victims of a mania the self-righteous display for requiring their targets to do as they say rather than as they themselves do:

“It is not easy to hear the stern denunciations of gin, and of the profligacy of the lower classes, proceeding from one of those well-fed, well-clad moralists, who never indulges in anything save sound old port, or the best malt-liquor, without calling to mind one of the pictures of him, whose sagacity in detecting the manifold weaknesses of the human heart, and penetrating its most hidden springs, is only excelled by his indulgence in judging its wanderings and weaknesses.” (Johnstone 488n)

Johnstone is that rarity, a Regency intellectual who also goes farther, to respect those ‘lower classes.’

The Manual reflects her reforming, transforming purpose at Tait’s . She explains for example, in a wry note at the outset of the chapter on “Cheap Dishes and Cookery for the Poor:”

“We are convinced that the art of preparing cheap dishes is much better understood by the intelligent poor, than by those who assume the task of instructing them. It is not, therefore, for the direct use of the poorer classes, but for the information of those who, from charitable motives, are anxious to devote part of the abundance which Providence has blessed them to their humble brethren, that this section is added to the Cook’s Manual.” (Johnstone 486)

More than a hint of Hawthorne’s disdain for the self-righteous reformer who invariably makes things worse is apparent from the passage. In common with other contemporary works including The Confessions of a Justified Sinner , James Hogg’s savage and funny 1824 novel satirizing murderous Presbyterian fanaticism, the Manual demonstrates that the Enlightenment ideal of secular tolerance pushed itself into the teeth of a less accommodating Romantic age.

10. A sort of surrealist manifesto.

As Davidson recognizes, the Manual represents some of the “most astonishing, even surreal writing on food ever undertaken.” (Davidson 705) Johnstone embeds a lot of the surrealism in those footnotes. In her appendage to the recipe for “Cheese to serve as a relish” Johnstone recounts a learned debate:

“This academic, histrionic, and poetical preparation has produced a good deal of discussion in its day…. The twenty-eighth maxim of O’DOHERTY is wholly dedicated to this tasteful subject, and his culinary opinions are worthy of profound attention. ‘It is the cant of the day,’ quoth sir MORGAN, ‘to say that Welsh Rabbit is heavy eating.’ I know this,--but did I ever feel it in my own case?--Certainly not.”

Sir Morgan considers rabbit delicate prepared in his preferred manner:

“I like it best in the genuine Welsh way… the toasted bread buttered on both sides profusely, then a layer of cold roast beef, with mustard and horseradish, and then on the top of all a superstratum of Cheshire thoroughly saturated while in the process of toasting with cwrw , or, in its absence, porter--genuine porter--black pepper, and eschalot-vinegar.”

That description by no means is the traditional Welsh preparation, while ‘cwrw’ is simply the generic Welsh term for beer, more probably ale, which hardly distinguishes it from porter, and both Johnstone and her readers would have found a rabbit ornamented with so much butter and beef unconventional in the extreme. Not, however, Sir Morgan:

“I peril myself upon the assertion, that this is not a heavy supper for a man who has been busy all day till dinner in reading, writing, walking, or riding--who has occupied himself between dinner and supper in the discussion of a bottle or two of sound wine, or any equivalent, and who proposes to swallow at least three tumblers of something hot ere he resigns himself to the embrace of Somnus.” (Johnstone 323n)

The real (Welsh) McCoy.

11. The wisdom of Sir Morgan O’Doherty. In other words the rabbit is by no means a rich savory--for the profligate drinker alone, and we should discount the sagacity of the sentiment. Sir Morgan, the fictive Irish creature of five Scottish contributors to the influential Blackwood’s Magazine , authors who also collaborated on the periodical's “Noctes Ambrosianae,” would have been familiar to readers of The Manual for ‘his’ farcical maxims and other pronouncements, including an 1821 entry called “Extracts from a Lost (& Found) Memorandum Book.”

The extracts cover “The Somnambulatory Butcher,” “Love Song of a Junior Member of the Cockney School” and various other targets of parody. (Wardle 722) Blackwood’s was particularly obsessed with denigrating the emergent idiom; among its putative adherents were the romantic poets, Dickens and other luminaries considered anathema by the conservative periodical. “Curse on the Cockney school of scribblers,” exclaims Sir Morgan, otherwise a champion of London and especially, along with the most intolerant of Tories, Dr. Johnson, its taverns. Accursed they may be, but cockneys would appear formidable enough opponents for Sir Morgan to decline combat, at least at times. They,

“who know nothing, have, by writing in praise of Augusta Trinobantum, (I use this word on purpose, in order to conceal from them what I mean,) made us sick of the subject.” (Hamilton 64-65)

The misdirection itself refers to the putative ignorance of the cockney, because the term, more usually ‘Augusta Trinovantum,’ apparently is an obscure Roman synonym for Londinium.

12. Jousting in the shadows, or, guerilla warfare hiding in plain sight.

The oblique reference by Johnstone to Blackwood’s itself entails another irony, for she edited its progressive rival, Tait’s Edinburgh Magazine. In its heyday under Johnstone Tait’s was the more influential of the two. According to an 1866 source, Tait’s “was conducted with much ability and fearlessness, and it rose at once to a large circulation…. mainly indebted to its elaborate and often eloquent reviews of books, for a long period written almost exclusively by Mrs Johnstone.” She also edited and published “new tales by the best writers, chiefly female authors.” (Conolly 244)

The periodical more generally “had a good reputation and circulation, in part, because William Tait and Christian Johnstone were leaders and shapers of Scottish public opinion.” (Fraser et al. 139) The fact that a woman could wield that much power in her place and time was unprecedented. Alexis Easley concurs that “her career… ‘seems today nothing short of miraculous.’” (Dudley Edwards 173 citing Easley) Pam Perkins strikes a similar sound:

“Christian Johnstone’s career was so unusual for a woman of her day that it is impossible to generalise from it and draw any wider conclusions about the role of women in journalism in the first decades of the nineteenth century.” (Perkins 280)

And yet, another irony, Easley considers her anonymous, or nearly so. She wrote much of her considerable output without attribution and under the ‘Dods’ or other pseudonyms, although the ruse failed to conceal her identity from elite Edinburgh.

As Dudley Edwards, who considers Johnstone one of the great editors of any period

observes, “although she was reclusive, she was much less anonymous, and kept her feminism visible. At the same time she had become much more critical of feminists who faltered.” (Dudley Edwards 173-74)

The creators of O’Doherty may have been as playful about Johnstone as she could be about them, friendly rivals perhaps rather than the haters prescribed by the satires of Sir Morgan. After all, in contrast to Johnstone Scott himself was another devout Tory and Unionist, leery of the transformations she hoped to encourage.

One source notes, with incomplete and underinformative understatement, that her husband, who published Scott, also “had business dealings with Blackwood’s .” (Monnickendam 136) In fact John Johnstone and his wife had extensive dealings with William Blackwood himself. Together they purchased the Edinburgh Weekly Chronicle . The Johnstones edited the paper but the arrangement could not last. According to a mid-nineteenth century source, “the principles of the paper were much too Liberal for their co-proprietor, who belonged to the old Tory party.”

By all indications it was an amicable divorce: Blackwood also commissioned Johnstone’s second novel, the three volume Elizabeth de Bruce , which sold some 1,400 undiscounted copies at a time when the standard Edinburgh edition ran to five hundred. (Conolly 244) Ideological and cultural arguments did not unravel the networks of sociability and friendship in Edinburgh.

At the time a number of authors, and unlike Mrs Dalgairns most women, published either anonymously or under a pseudonym. The creators of Sir Morgan of course were aware of the fact. “It is the prevailing humbug for authors,” he complains,

“to abstain from putting their name on their title pages; and well may I call this a humbug, since of every book that ever attracts the smallest attention, the author is instantly just as well known as if he had clapt his portrait to the beginning of it.” (Hamilton 55)

Sir Morgan speaks in general of the practice, one of the few conventions of the age to which Johnstone adhered, but of the ‘undisclosed’ authors he decries she not only was the most influential but, as Dudley Edwards explains, anything but unknown, especially in the circles orbited by the creators of Sir Morgan. Nor had she any sympathy for the Blackwood’s project, which would have made her an attractive target. Literary Edinburgh was a brilliant world but it was a small one. Its inhabitants reveled in oblique as well as explicit intellectual antagonism, but not, as Hume observed, with the actual antipathy of their counterparts in the London clubs, not least of Dr Johnson, one of the great haters of that or any age.

On the subject of small worlds, in this case the one of British publishing more generally, Sir Morgan has something to say about John Murray, which if true would explain his reluctance to take on The Practice of Cookery. Notwithstanding the special pleading of Basil Hall, Mrs Dalgairns and her project were atypical in terms of the firm’s focus:

“John Murray is a first-rate fellow in his way, but he should not publish so many baddish books, written by gentlemen and ladies, who have no merit except of figuring in the elegant coteries of May-fair. There seems to me to be no greater impertinence than that of a man of fashion pretending to understand the real feelings of man.” (Hamilton 22)

So snobbery and his intended audience may have had more to do with the diffidence of John Murray than sexism.

Haters gonna hate.

Haters gonna hate.

13. The character of Mistress Dods. Johnstone paired her deeply controversial feminism with a similarly fraught mission to bridge the worsening class divide in a rapidly industrializing Britain, beset as it was by the dislocation attending the transformation from a less urban economy. According to one commentator it was nothing less than her mission as editor of Tait’s “to facilitate a dialogue between middle-class and artisan-class writers and readers,” her effort as editor “to construct a national literature of reform that would ‘solve’ conflicts and inequities in the Victorian [sic] class and gender system.” (Easley 264)

14. The character of Sir Morgan O’Doherty.

Despite her passion for reform Johnstone could poke fun at herself by invoking Sir Morgan, who trumpets the superiority of Blackwood’s to all other journals. More ironic still, the O’Doherty persona is devoutly sexist and illiberal. “There is no such thing as a female genius,” he declares, with the exceptions of Sappho and Madame de Staël. Sappho of course is reputedly lesbian, although each generation determines her sexuality for itself and Sir Morgan’s ascribed to her a preference for men.

More irony; he admired the “Ode to Phaon” which, however, was a hoax that she did not write.

Of de Staël’s considerable output Sir Morgan mentions only Corinne , a story of a poetess’ devotion to a noble which, oddly, she hijacked as a vehicle for extolling the landscape and culture of Italy juxtaposed against a robust ‘Nordic’ ethos that in fact she preferred. In any event Sir Morgan considers both works “mistress-pieces” but only because they describe womens’ infatuation with men;

“ ….of these two good things the inspiration is simply and entirely that one glorious feeling, in which and which alone, woman is the equal of man.” (Hamilton 26)

Then consider Maxim the Thirty-Sixth; while Delphic, it is unquestionably misogynistic and possibly lascivious. “The next best thing to a really good woman,” he writes, “is a really good natured one.” (Hamilton 45) Erasing theoretical doubt about his attitude, Sir Morgan notes later that “[a]ss-milk, they say, tastes exceedingly like woman’s. No wonder.” (Hamilton 59)

His maxims range across many other subjects and the political opposition receives steady fire. Asses reappear in the opening broadside: “A Whig is an ass.” (Hamilton 14)

Another salvo:

“Whenever there is any sort of shadow of doubt as to the politics of an individual, that individual has reason to be ashamed of his politics--in other words, he is a WHIG. A Tory always deals above board.” (Hamilton 39)

Sir Morgan would find our own tribal intolerances congenial. “He whose friendship is worth having,” something a Trumpy would say, “must hate and be hated.” (Hamilton 51)

“There are four kinds of men,”on that count Sir Morgan believes,

“the Whig who has always been a Whig,--the Tory who has once been a Whig,--the Whig who once has been a Tory,--and the Tory who has always been a Tory. Of these I drink willingly with only the last,--considering the first as a fool, the second as a knave, and the third as both a fool and a knave; but if I must choose among the others, give me the mere fool.” (Hamilton 46)

Immediately after admitting those prejudices Sir Morgan pronounces on drinking companions more generally to enunciate a universal verity, coining a congenial verb in the process. “Never boozify a second time with the man whom you have seen misbehave himself in his cups. I have seen,” Sir Morgan explains,

“a good deal of life, and I stake myself upon the assertion, that no man ever says or does that brutal thing when drunk, which he would not do or say when sober, if he durst .” (Hamilton 47)

“Liberality, conciliation, &c. &c., are,” he goes on to insist, “roundabout words for humbug in its lowest shape.” He goes so far as literally to demonize the opposing party:

“One night lately I had a very fine dream. I dreamt I was in heaven. Some of the young angels were abusing the devil bitterly. Hold, hold! said an ancient-looking seraph, in a very long pair of wings, but rather weak in the feather,--you must not speak in this way. Do not carry party-feelings into private life. The devil is a person of infinite talent--a very extraordinary person indeed. Such a speaker! &c. &c. &c.” (Hamilton 86)

The treatment of devils culinary is no less severe, in Maxim the One Hundred and Twelfth:

“Some people talk of devils; all our common devils are damnable. The best devil is a slice of roasted ham which has been basted with Madeira, and then spiced with cayenne.” (Hamilton 110-11)

The maxims in no way amount to the running Irish joke that might have been anticipated, and both tone and content indicate that the creators of Sir Morgan endorse his reliably Tory perspective on matters political as well as cultural.

15. The apolitical punster blues.

Turning apolitical, number three amounts to a tirade against people who pun, later qualified by number twenty: “Puns are frequently provocative,” particularly when dining with a nabob. (Hamilton 24-25)

In the ordinary course however:

“A punster, during dinner, is a most inconvenient animal. He should, therefore, be immediately discomfited. The art of discomfiting a punster is this: Pretend to be deaf; and after he has committed his pun, and just before he expected people to laugh at it, beg his pardon, and request him to repeat it again. After you have made him do this three times, say, ‘O! That is a pun…. ’ If well done, the company laugh at the punster, and he is ruined forever.” (Hamilton 10-11)

That presupposes the punster had been unacquainted with his nemesis, and that the nemesis had not previously participated in conversation over dinner, but in those specific circumstances the tactic may achieve a salubrious enough result.

16. More matters religious.

Maxim the Eighty-First identifies the Twenty-Fourth as “a most erudite and important one,” and so it is:

“I do not agree with Doctor Adam Clarke’s translation of… Genesis. I think it must mean a serpent, not an ourang-outang…. There is, after all, no antipathy between serpents and men naturally…. ” (Hamilton 28)

Clarke was a distinguished Methodist theologian and early abolitionist, on both counts an obvious target of ridicule for the High Tory Blackwood’s gang. To illustrate an absolute, One-Hundred Twenty-Eighth Maxim, “Despise humbug,” Sir Morgan begins a story with “I once dined with Wilberforce…, ” and the reader will not require a description to anticipate the kind of racism that ensues. (Hamilton 129)

Perhaps a worse crime for the cigar smitten O’Doherty persona, Clarke decries the abuse of tobacco with his Dissertation on the Use and Abuse of Tobacco wherein the Advantages and Disadvantages attending the Consumption of that Entertaining Weed are Particularly Considered, Humbly Addressed to all the Tobacco-Consumers In Great-Britain and Ireland, but especially to those among Religious People. It begins with a keynote by an ‘S.,’ neither John nor Charles, ‘Wesley:’

“To such a height with some is fashion grown,

They feed their very nostrils with a spoon,

One, and but one degree is wanting yet,

To make our senseless Luxury complete;

Some choice Regale useless as Snuff and dear,

To feed the mazy windings of the ear.”

17. Some matters customary, because custom matters.

Sir Morgan echoes Burke in his reverence for tradition. It is a legitimate enough concern. “Of late,” he complains, “they have got into a trick of serving up the roasted pig without his usual concomitants.” That sort of thing leads to what in the woeful parlance of our own time would be considered erasure: “Take away the customs of a people, and their identity is destroyed.” (Hamilton 85-86)

Sir Morgan takes, as Johnstone indicates, a recurring interest in foodways and boozification. He likes “your real turtle-soup,” “peppery” mulligatawny, and especially punch and grog, on which his opinions are as strong as his recipes. (Hamilton 72)

Ahead of its time, and also very much its product, the O’Doherty persona prefers cayenne, savory pies, especially grouse pie, and advocates culinary localism, not least when the subject is fish. “In order to know what cod really is, you must eat it at Newfoundland.” Not, however, that anything indicates he ever had been there. “Herring,” in the same way, “is not worthy of the name, except on the banks of Lochfine in Argyleshire [sic]; and the best salmon in the whole world is that of the Boyne.”

Sir Morgan’s ire is nearly as fixated on Dr Kitchiner, not the most predictable target, as on the Whig. Taking flight again to speculation, Sir Morgan claims that “Dr Kitchiner, in all probability, never tasted any one of those things, and yet the man writes a book upon cookery!” (Hamilton 101, 100) In an extended instructional series on punch; “As some folk mention Dr Kitchiner, I may as well dispose of him.” (Hamilton 67)

Maxim the Twenty-Second, which is not really a maxim, combines politics and consumption to complain about “a kind of mythological jacobitism going on just now.” In counterattack ‘O’Doherty’ “long had an idea of writing a dithyrambic in order to show these fellows how to touch off mythology.” A sample:

“Come to the meeting, there’s drinking and eating,

Plenty and famous, your bellies to cram;

Jupiter Ammons, with gills red as salmon,

Twists round his eyebrows the horns of a ram.Juno the she-cock has harnessed her peacock,

Warming his way with a drop of a dram;

Phoebus Apollo in order will follow,

Lighting the road with his patent flam.Cuckoldy Vulcan, dispatching a full can,

Limps to the banquet on tottering ham;

Venus her sparrows, and Cupid his arrows,

Sport on th’ occasion--fine infant and dam.”

&c. &c. &c.: Sex and drugs and rock and roll, Edinburgh Enlightened style. “There,” as Sir Morgan exclaims, “is real mythology for you!” (Hamilton 26-27)

18. Intolerant calls for tolerance.

All this is a sort of Mad magazine of its time, (slightly) less puerile and (a very little) more intellectual but aimed at adults rather than adolescents. Then again, some maxims are so sound they should remain required reading, the Thirty-Fourth, prefiguring Johnstone herself, among them:

“It is a common thing to hear big wigs prosing [sic] against drinking as ‘a principal source of the evil that we see in this world…. ’ There cannot, however, be a more egregious mistake. Had Voltaire, Robespierre, Buonoparte, Tallyrand [sic], &c., been all a set of jolly, boozing lads, what a mass of sin and horror, of blasphemy, uproar, blood-thirsty revolution, wars, battles, butcherings, ravishings &c. &c. &c… had been spared… !” (Hamilton 43-44)

That all is fair enough in general when it comes to Robespierre, and Talleyrand for one was notoriously venal and voluptuary. Then again he was not all bad, among other things a devoted raconteur, gourmand and oenophile. He hired Carême and acquired Haut Brion, if only for a few years. His willingness to bend in the breeze allowed him to betray Napoleon; Talleyrand’s convivial guile did broker a lasting if reactionary peace following the Congress of Vienna.

On another species of proscriptive scolds, the judgment of Sir Morgan is more acute. “If,” he insists, “prudes were as pure as they would have us believe, they would not rail so bitterly as they do. We do not thoroughly hate that which we do not thoroughly understand.” (‘O’Doherty’ 62)

And: “People often say of a man that he is a cunning fellow. This can never be true--for if he were, nobody could find out that he was.” (Hamilton 117)

Also on the desirability of self-deprecation, or maybe self-discipline, Sir Morgan offers a reminder that, while its catalytic effect cannot be discounted, Facebook did not create the obsession of so many narcissists with self-indulgent displays:

“Nothing is more disgusting than the coram publico endearments in which new-married people so frequently indulge themselves. The thing is obviously indecent; but this I could overlook, were it not also the perfection of folly and imbecility. No wise man counts his coin in the presence of those who, for aught he knows, may be thieves--and no good sportsman permits the pup to do that for which the dog must be corrected.” (Hamilton 48)

The austere, severe Mrs Dalgairns could not provoke this kind of digression into the wiles of the fictive Sir Morgan, an infirmity her more practically inclined reader might applaud.

19. Those fantastical footnotes.

To return to Johnstone and her footnotes from the Manual , the one “To Roast Hare, Fawn, Or Kid” is not atypical, and takes elliptical exception to Fergus Henderson’s subsequent insistence on consumption from Nose to Tail . “A hare’s ears are reckoned a dainty by some epicures” but, Johnstone reminds her reader, “they must be singed and cleaned.” Why however bother when: “The Cleikum Club held them in equal respect with duck’s feet, but were very tolerant of those who admire them.” (Johnstone 114n)

Johnstone delights in wordplay throughout the Manual. Comparing the newly fashionable “Des Déjeueners à la Fourchette” to tiffin, the light meal beloved of the Raj, and highlighting the pretense of those in Britain who use the term, a mysterious “P. W.” introduces a genteel but anonymous woman:

“The same articles will generally answer for luncheons or comfortable collations--and those refreshments affectedly termed TIFFINS. A worthy lady of our acquaintance, that we are morally certain never had a family quarrel in her life, assures us that she regularly tiffs with the Doctor and the bairns every day, at one o’clock precisely.” (Johnstone 75n)

Urban England takes serial salvos from Mistress Dods, who deplores the practice of its poorer inhabitants to insist on consumption of undersized roast meat they cannot really afford instead of subsisting, like sensible Scots, on cheap, cheering broths and stews.

20. Beware the baker.

Johnstone warns against the stratagems of the urban baker. In an incongruous addition to her section “On Baking Meat,” she warns:

“Bakers’ ovens have one great drawback;--they are accused of being sad suckers in, indeed real sponges for gravy; so that they often indemnify bakers’ apprentices for the trouble saved the cook.”

In part Johnstone shares the traditional prejudice for baking as opposed to roasting meat, especially beef: “The noble sirloin disdains to be cribbed in the oven” and although the lesser rump may be “esteemed a delicacy” a footnote disavows the dish. “The Cleikum did not prove,” that is, approve of, “this receipt.” (Johnstone 115, 115n)

Do the bakers overcook the meat, or are their ovens sponges for the gravy because the apprentices sponge off customers by stealing it? Either way the phenomenon is unfortunate. “Besides,” Johnstone continues,

“meat is seldom got home in season from those wholesale receptacles for all manner of joints; and about the dinner hour, what dismay is often created by the face of the maid,--

‘Who comes with most terrible news from the baker,

---------------------------That insolent sloven!--

Who shut out the pasty when shutting his oven!’” (Johnstone 115-16)

If bakers in general are unreliable and their apprentices pilfer, London bakers are bold in their propensity to bait and switch by increment but, it appears, only when cooking mutton. The footnote for instructions “ To grow a shoulder or leg of mutton ,” signed like some but not others by a mysterious ‘P. T.,’ describes the foolproof formula.

“This art is well known to the London bakers. Have a very small leg or shoulder; change it upon a customer for one a little larger, and that upon another for one better still, till by the dinner hour you have a heavy excellent joint in lieu of your original small one.” (Johnstone 116n)

Another take on loaves and fishes tells the tale of how a London sharpie stretches his ham with eleemosynary effect.

“A few years since the proprietor of Vauxhall Gardens lost his celebrated carver of hams, when he advertised for a new operator in that department of harmless anatomy. One of notoriety applied, when the worthy proprietor asked him how many acres he could cover with one fine ham; upon which he replied, ‘he did not stand upon an acre or two, more or less, but could cover the whole of his gardens with one ham.’ On this he was instantly hired, and told he was the very fellow for this establishment, and to cut away for the benefit of the concern and mankind at large.”

As Johnstone deadpans in the text above the note, “the object is to cut thin.” (Johnstone 116n, 116)

21. The puncture of all pretense.

Satire infuses other footnotes. Friar’s balsam, an old cold remedy based on evergreen extracts and, in the recipe from Mistress Dods, aloe, frankincense, myrrh and St John’s wort is called, “in zealous Protestant families” ‘aromatic tincture instead;’ she recommends aging it for a month in the stableyard dunghill. (Johnstone 367n)

Elsewhere Johnstone punctures the pretense of Francophiles. She is historically accurate in explaining that

“Modern French professors have a few grand sounding names which they bestow on elementary gravies and sauces… and these, once defined and properly understood, remain ever the same.” (Johnstone 138n)

After all it was not until the culinary nationalist Carême appropriated various sauces from all over Europe by giving them new names that they became considered ‘French.’ Johnstone recognizes that even the most English of traditional sauces, ‘melted butter’ made with liquid, butter and sometimes a bit of acid, was becoming identified as “ Sauce blanche ” even though foreigners including Voltaire parodied it as the only sauce in England. She therefore also lists the sauce, which she still considers “perhaps the most appropriate for all vegetables,” by that name in the section on “French Cookery.” (Johnstone 358n) Carême’s campaign of misdirection remains an international success.

A preparation of roast pork stuffed with herb butter and basted with sage infused olive oil “though a French, is no bad receipt.” (Johnstone 99n)

Mistress Dods herself discounts the influence of the ‘Auld Alliance’ in the Scots kitchen. As for salmis, those “favourite dishes with epicures, both on account of the excellence of their constituent parts, and their elaborate and piquant composition, [t]hey are in fact a species of moist devils ,” the traditional, and fiery, English preparation disdained by Sir Morgan in most of its guises. “For thoroughbred English palates more hot seasonings will be requisite than are used by the French,” a distinction that was correct both in terms of salmis or devils in particular and of the two nations’ traditional attitudes to seasoning more generally. (Johnstone 350n)

Tastes, however, were changing. The emergent and interrelated cults of politeness and sensitive sensibility had begun infiltrating culinary taste: “Epicures of the modern school begin to dislike the flavour of anchovy in meat-dishes…. It is certainly, though a high, not a very delicate relish,” the note a harbinger of the less exuberant culinary era to come. (Johnstone 126n)

22. An immodest disclosure.

Mrs. Johnstone does not spare her own ambition. In a self-mocking note to something as ubiquitous on tables of the period as a recipe for “Small Tea-Cakes,” she ‘apologizes’ for an editorial failing:

“The greatest difficulty we have experienced in correcting the various editions of this immortal work has been in restraining the headlong torrent of our extensive culinary knowledge within reasonable bounds--what to tell, and what to suppress,--not when to begin, but where to have done prescribing, is our stumbling-block. We confess a strong natural leaning to the side of plenty--nay, of abundance--and of good-nature.” (Johnstone 448n)

The extent of Johnstone’s actual culinary knowledge cannot be considered a joke, as the admiration of the Manual since its publication, contemporary critics and then others including Mrs Grigson indicates. Contemporary reviewers understood that, and highlighted it as among the best cookbooks of the age. Although Charles Rintoul at the Spectator believed The Practice of Cookery eclipsed a number of its competitors for useful guidance, he exempted ‘Dods.’ After assessing the work of “old standards” including Glasse, Johnstone, Kitchiner and Rundell, he turned to Mrs Dalgairns:

“We think--we are not sure--that we shall put away Rundell and Kitchener [sic] for Mrs Dalgairns. She is far more copious than they are, far more various, and to us more novel. It is not a gourmand’s book neither does it pretend to be…. ” (Rintoul; Williamson xxxvii)

In addition to endorsing the classic Glasse and creative Manual by inference, the Rintoul review reinforces a notion that The Practice of Cookery was the less sophisticated of the two in culinary as well as literary terms.

23. Is it Scottish?

Johnstone’s Manual did, according to Brears, lean to the side of plenty in describing some fifty seven recipes as Scots “national dishes of particular importance,” this an increase from the three that Elizabeth Cleland identifies in her New and Easy Method of Cookery, which first appeared in Edinburgh during 1755. He maintains of the ‘Dods’ dishes that “many of these are as much, if not more English than Scottish.” (Brears xxiv)

Regardless of origin, by 1827 the Johnstone recipes had shed any previous identity to become recognizably Scottish to contemporaries. On that score they are Scots indeed, for the twins of tradition and identity are the imaginative creation of human culture. Before Scott undertook his ‘creative’ Scottish nationalist cultural project tartan may not have been so widespread as conventional wisdom would have it, but by the time the Manual appeared it had become an ironclad Scots identifier.

And despite himself Brears does consider at least one of Mrs Cleland’s recipes peculiar to Scotland, in fact peculiar to her. Despite its name, the “one for Yorkshire pudding… is virtually unique in boiling it for three hours, rather than cooking it under the meat.” (Brears xxv) He also recognizes that much of the nomenclature in the New and Easy Method and many of the kitchen tools, weights and measures it describes are recognizably creatures of Scotland and nowhere else.

As for The Cook and Housewife’s Manual , it is a lot more than an instructional tract, more an interdisciplinary creation of Scottish culture. Johnstone interweaves social and political commentary with idiosyncratic humor to describe a vibrant national culinary culture while advocating a tolerant secular sensibility. The Manual is sufficiently original that it transcends genre or nation, the enduring literary creation of Christian Isobel Johnstone alone.

Note:

For more on Christian Isobel Johnstone, see Blake Perkins, “Christian Isobel Johnstone and The Cook and Housewife’s Manual by Meg Dods,” Petits Propos Culinaires 105 (April 2016) 16-41; on traditional Acadian foodways, Perkins, “A meditation on Canadian Foodways;” and “Salt in the service of seasoning and the seasons, and a beautiful child born of need: the Atlantic fricot ,” both at www.britishfoodinamerica.com no. 21 (September 2011).

Sources:

Anon., “Catherine Dalgairns: 19th century Canadian/Scottish cookbook author,” Cook’s Info , https://www.cooksinfo.com/catherine-emily-callbeck-dalgairns (n.d.) (accessed 29 April 2021)

Peter Brears, “Introduction” to Elizabeth Cleland, A New and Easy Method of Cookery (Prospect Books, Totnes, Devon 2005)

John Cambridge, A Description of Prince Edward Island in the Gulph of Saint Lawrence, North America (2d ed. Bristol 1818)

Anand Chitnis, The Scottish Enlightenment & Early Victorian English Society (London 1986)

M.F. Conolly, Biographical Dictionary of Eminent Men of Fife (Edinburgh 1866)

Alan Davidson, The Oxford Companion to Food (Oxford 1999)

Owen Dudley Edwards, “Carleton’s unknown Scottish critic: Christian Isobel Johnstone,” Clogher Record vol. 21 no. 3 (2014) 161-76

Alexis Easley, “‘Tait’s Edinburgh Magazine’ in the 1830s: Dialogues on Gender, Class and Reform,” Victorian Periodicals Review vol. 38 no. 3 (Fall 2005) 263-79

Hilary Fraser, Judith Johnston & Stephanie Green, Gender and the Victorian Periodical (Cambridge 2003)

Douglas Gifford & Dorothy McMillan (ed.s), A History of Scottish Women’s Writing (Edinburgh 1997)

Gordon Goodwin, “Johnstone, Christian Isobel,” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford 1885-1900)

Jane Grigson, The Observer Guide to British Cookery (London 1984)

Thomas Hamilton et al. , The Maxims of Sir Morgan O’Doherty, Bart. (Edinburgh 1849)

Michael Hyde, “The Role of ‘Our Scottish Readers’ in the History of Tait’s Edinburgh Magazine ,” Victorian Periodicals Review vol. 14 no. 4 (Winter 1981) 135-40)

Christian Isobel Johnstone (writing as ‘Mistress Margaret Dods’), The Cook and Housewife’s Manual (Edinburgh 1827)

Andrew Monnickendam, “The Good, Brave-hearted Lady: Christian Isobel Johnstone and National Tales,” Atlantis vol. 20 no. 2 (December 1998) 133-47

Pam Perkins, Women Writers and the Edinburgh Enlightenment (Amsterdam 2010)

Sarah Richardson, The Political Worlds of Women: Gender and Politics in Nineteenth Century Britain (London 2013)

Charles Rintoul, ‘Review,’ the Spectator no. 50 (13 June 1829)

Ralph Wardle, “Who was Morgan O’Doherty?” Proceedings of the Modern Language Association vol. 58 no. 3 (September 1943) 716-27

Mary Williamson, “The Publication of ‘Mrs. Dalgairns’ Cookery’: A Fortuitous Nineteenth-Century Success Story,” Papers of the Bibliographical Society of Canada vol. 45 no. 1 (2007)