Traditional Yorkshire Food

1. But wait, there’s more!.

In 1952, Dorothy Hartley published the idiosyncratic and delightful Food in England. With its brawny line drawings, raft of recipes, brisk judgments and extensive quotations, Food in England is a classic, and remains in print.

In 1952, Dorothy Hartley published the idiosyncratic and delightful Food in England. With its brawny line drawings, raft of recipes, brisk judgments and extensive quotations, Food in England is a classic, and remains in print.

Not quite a survey, more an extended discussion of foods and ways to prepare them that Hartley finds of interest, nothing else like Food in England has appeared anywhere. Not that others have not tried; in 2007, for example, Marwood Yeatman rather self-consciously, or perhaps vaingloriously, attempted a contemporary counterpart The Last Food of England, which adds subjects, like sustainability, not exactly au courant at midcentury. It is unfortunately a poorly written, unfocused and disorganized mess.

Now along comes Traditional Food in Yorkshire by Peter Brears. At the outset of his bibliography Brears notes that his “sources have been used to provide much of the information contained in this book, and will enable the reader to build up a much more comprehensive view of the traditional life of the people of Yorkshire.” (Brears 346)

It is hard to credit his second assertion. For that matter, Traditional Food bears a misleading title. Brears has gone a considerable way beyond describing Yorkshire foodways, to assess the working and domestic lives of the county’s people, a task he has undertaken with compassion, affection and aplomb. Readers will meet coal miners, farmworkers, ‘fisherfolk,’ spinners, weavers and workers in towns. It requires imagination to guess what is left to learn about these traditional lives from any other source.

Traditional Food is an outlier, an effort that not only documents its assertions with extensive sources, but also does the job with a literacy and verve that are seldom seen in in the generally dismal field of culinary history.

2. A time of change.

Brears has chosen an era, from 1800 through about 1920, of wrenching transformation. In 1800, people in Yorkshire

“still followed many traditions and practices which had hardly changed since the Middle Ages. Most communities were long-established and static. They grew their own foods and cooked them to centuries-old recipes passed on from one generation to the next slowly by means of practical experience.” (Brears 9)

Within a generation all would change. The North of England became the cauldron of the first industrial revolution: Yorkshire itself would become “the world’s major steel-working, engineering and wool-textile region,” while Hull went from sleepy town to “a great international port,” for a while second only to London in all of Britain, for transshipment and export of all those products. (Brears 9) By the 1830s and 40s, conditions had become horrific in the instant industrial cities like Huul itself, Bradford or Leeds; “many, if not most, of the urban poor were living almost entirely on bread, butter, tea and coffee…. ” (Brears 67)

Predictably enough, “deficiency disease” devastated the working class, “particularly when combined with insanitary, overcrowded and poorly ventilated living quarters.” At Halifax early in the nineteenth century, life expectancy declined from 55 years for “Gentry, etc.” to 22 years for “Labourers & Mill operators.” (Brears 67)

Despite or because of his attachment to the preindustrial traditions of Yorkshire, Brears scans the new era with a clinical eye.

3. Revolutions in tandem.

Rabbit seller in rural Yorkshire

Things were not so bad, if not luxurious, for others swept into bewildering change. Another revolution, unseen to our own popular history, erupted simultaneously to enable the onslaught of the industrial one that transformed the world. “In the decades around 1800, the East Riding of Yorkshire rapidly developed into one of the richest agricultural regions of England as thousands of acres… were enclosed and improved.” (Brears 13)

That in itself caused dislocation, as the improving landlords evicted tenants and a burgeoning urban population’s need for food created a demand for increased agricultural production that was met by an influx of hired hands. At least the more fortunate farm workers, many of whom lived with their employers, found plentiful food.

In contrast to the industrial towns, where the majority of the inhabitants born in the countryside lost their traditional patterns of life, the primacy of custom remained intact in the agricultural world. Master and hired hand shared a sort of hierarchical democracy.

This social structure continued to be reflected at table. The owner of the farm sat at its head;

“he carved and served the meat to the men in strict order of precedence…. If the carver was really skillful, he would flick the slices of meat from the point of his knife directly on to each plate in turn.” (Brears 15)

Pies of curd or seasonal fruit lined the table, and ritual ruled their consumption:

“Each man helped himself to slices of pie, always finishing one pie before starting another, and always cutting the pie in the distinctive East Yorkshire manner. Holding the plate steady with two fingers on the edge of the pie, the first cut was made from the centre to the left side of the fingers, a second cut then being made from half an inch short of the centre to the right side of the fingers.” (Brears 15)

Diners took their turn cutting counterclockwise through the pie, “until the last slice was left with a hexagonal piece at the centre.” (Brears 15) The procedure ensured that “everyone had the same proportion of crust to filling, and also that no one ever handled anyone else’s piece of pie.” Anyone neglecting the ritual got his knuckles rapped with the flat of the master’s carving knife. (Brears 15-16)

This is the kind of narrative that brings depth and color to historical writing.

Other than his ability to reward favorites with the choicer cuts of meat and enforce the customary cutting of the pies, even the household head acquiesced in the dissipation of hierarchy at the table, however transient, by taking his turn at the pie.

4. Anthropological integrity.

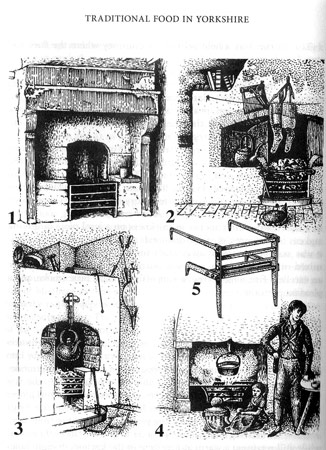

Brears is an accomplished artist and curator, so it should be no surprise that Traditional Food in Yorkshire is laden with his clean line drawings and the kind of empirical data (the book includes tables of domestic inventories) that ordinarily appears only in anthropological history of a high order which, it happens, includes Traditional Food.

Brears is an accomplished artist and curator, so it should be no surprise that Traditional Food in Yorkshire is laden with his clean line drawings and the kind of empirical data (the book includes tables of domestic inventories) that ordinarily appears only in anthropological history of a high order which, it happens, includes Traditional Food.

Beautifully rendered perspectives and interiors show the cottages and terraces inhabited by artisans, fishing families, miners and others manage to be moving as well as informative, a tribute to Brears’ affection for their inhabitants.

The illustrations to the chapter “Fuel and Fireplaces,” might be even better for the surprise factor alone. They run from spades specially designed to dig peat to a surprising variety of hob grates, iron ovens (Brears is right that “the first generation… was beautifully designed,” as his drawings demonstrate) and range accessories for are nothing short of spectacular. (Brears 86) They complement the narrative to demonstrate the aesthetic and technical ingenuity of the first industrial revolutionaries.

5. On to the food.

None of this should suggest that Brears has deceived his readers by neglecting the food. It would appear that Brears chose his title not as a prescriptive descriptive but rather to emphasize the salience of foodways to popular culture before the creation of a relatively anodyne mass market, ironically enough wrought initially by industrialization in the North of England itself. As Brears explains,

“[h]ome cookery was always far more than just a means of providing meals. It was perhaps the most significant and revealing aspect of domestic life, reflecting the physical, economic and social environment of each family within its community. Its history is that of all Yorkshire people, and through it we can more fully appreciate and experience the challenges and achievements of past generations.” (Brears 11)

Nobody has stated the case for culinary history in better terms.

The book includes lots of authentic recipes, although none for vegetables, perhaps reflecting the Yorkshire practice of serving them with utmost simplicity. Indeed most of the traditional recipes that Brears chronicles are almost laughably simple and none the worse for that. They rely on good local ingredients like heritage pork and homely northern produce to instill intense flavor into a typical preparation.

Ham cake is nothing but a thick slice of the famous Yorkshire ham encased in a simple crust shortened with lard; no herb or spice, no aromatic vegetables, nothing but cured pork and pastry. It is, as Brears maintains, “delicious, as all the juices from the gammon,” an English synonym for wet cured ham, “are absorbed in the pastry.” (Brears 166)

A good ham cake does not even require mustard, and traditionally did not get any; it was “carried out to workers in the harvest field.” (Brears 166) This, incidentally, reflects the earliest historical purpose of pie. Plain pastry was cheaper than a cooking vessel, tasted good, provided the calories required to sustain the long, strenuous workday, and obviated the need for knife and fork. It is a justifiable exaggeration to consider ham cake an embodiment of Yorkshire’s storied working class culture in its marriage of stolid practicality and simple delight.

If the misdirection of ham cake’s name also says something about English eccentricity, things like hardcakes, poverty cakes and sad cakes speak to English understatement, a trait now in short supply outside the North. Like ‘bitter,’ in another nation a marketing nightmare for so bracing a beer, these modest names belie a revelatory taste. Like the ham cake, or like the celebrated Yorkshire pudding, their simplicity is their enduring grace.

It is so difficult to get Yorkshire pudding right that conventional wisdom locates decent ones only in Yorkshire itself. That is untrue, but the prevalence of the misunderstanding underscores how hard it can be to cook the simplest--and sometimes most elementally satisfying--of foods. Traditional Food offers the necessary guidance with concise, clear recipes.

6. The accuracy of extravagance.

It would be extravagant to compare Traditional Food to Hartley’s Food in England; extravagant but accurate. Brears has done for Yorkshire what Hartley did more generally and less deeply for England writ large. If his style and structure are less idiosyncratic or endearing than hers, they also are less frustrating and, in historiographical terms, better.

Traditional Food in Yorkshire is a minor masterpiece of social and cultural history. Support the Prospect Books imprint and buy a beautifully produced copy.