Factual fiction, featuring strange birds, narcotics, romantic foodways, a quack doctor & Things: Part 1 of 3.

Two books written some seven decades apart consider the contours of British foodways through the lens of fiction, a significant source of evidence that historians tend to neglect or discount. Fiction after all by one definition is the work of imagination. By another it is a means to higher truth or heightened understanding of the human condition. The defter hand also may render fiction more reliable than what passes for the intentionally objective account that, the influential Yale school or ‘Hermeneutic Mafia’ insists, the human mind cannot create.

Critical controversy.

The Yale school consists, or consisted anyway, of a sprawling group of brawling critics obsessed for the most part with derivations and disputations concerning Jacques Derrida and his poststructuralist theory of deconstruction. Back during 1986 in a satirical essay for The New York Times Magazine Colin Campbell provided a decent capsule definition of the theory:

“Because the ‘language’ of a text refers mainly to other ‘languages’ and texts--and not to some hard, extratextual reality--the text tends to have several possible meanings, which usually undermine one another. In fact, the ‘meaning’ of a piece of writing--it doesn’t matter whether it’s a poem or a novel or a philosophic treatise--is indeterminate…. The text and its readings are everything. Authors, history and other contexts are secondary.”

It should be noted that deconstructionists themselves cannot, or will not, explain their theory with anything approaching that kind of clarity. They take themselves most seriously,and it is not unfair to infer that for them obscurity is everything. For that and other reasons deconstruction has been derided from left, right and center variously as “far too impatient with the multiple, practical functions of language;” “an empty, elitist, bourgeois game;” and sheer escapism.

Harold Bloom, until his death the éminence grise of the Yale critics, loathed not just the deconstructionists, but also the neoconservative critics (“fourth-rate reactionaries”), “punk ideologues, vicious feminists and neo-Stalinists” (one young Marxist colleague is “a horse’s ass”) he found around him. “To find out what’s going on at Yale now,” he tells Campbell, “is beyond my power.” (Campbell)

Strange birds.

Although Oxford Bibliographies describes him as “probably the most famous literary critic in the English-speaking world” and several of his books became unlikely bestsellers, Bloom was a bit batty himself. Out of the ether he laments of the odious Dr. Johnson that “I shall never write anything like that, alas. Alas, alas, alas.” An elegiac Bloom likes ‘alas.’ Campbell found that “listening to him” it was possible to “almost hear the kaawhoop-whoop whoop of hermeneutic hoopoes,” hoopoe a flamboyant and eccentric looking species of bird.

From the right at Yale itself Rene Welleck, known as “a fair-minded critic of critics,” attacked deconstruction for its “allegiance to nihilism.” He calls it “a prisonhouse of language” in which words refer only to other words and considers its “rejection of the very ideal of correct interpretation in favor of misreading, the denial to all literature of any reference to reality… symptoms of a profound malaise.” (Thomas; Campbell)

Derrida himself, a consummate obscurantist, has not always assisted the cause of his acolytes. On a call from France with Campbell about, among other things, Bloom,

“Derrida says that… he will be at Yale for five weeks. Until then he cannot discuss philosophy or politics or his American cult over the telephone. ‘As you can imagine,’ he says amiably, ‘all this is very controversial, very dangerous, really.’ Is it true that he and Bloom were born on the exact same day? ‘This is a factual question,’ Derrida replies. ‘I answer with no hesitation. I was born on the 15 th of July, 1930.’”

It gets better:

“But that was four days after Bloom, he is told. ‘He is older than me, he has more experience,’ Derrida says--and in any case, Bloom is no deconstructor. Might Derrida abandon deconstruction when he reaches Bloom’s age? ‘Perhaps,’ the philosopher answers.”

For his part Bloom, “who has heaped so much scorn on Yale,” is asked by an incredulous Campbell “where, after all, one might best study literature. ‘If somebody asked me’ (why does he say that? someone has asked), ‘I would say Yale University, alas.’” (Campbell)

Bloom, the elder.

A tamer time.

Decades earlier Arnold Palmer, in blissful ignorance of the swirling chaos that would engulf literary studies, attempted to untangle the knot of dining habits displayed by the British gentry through an approach that contrasted with deconstruction, its discontents and those discontented with it. To discern those dining patterns that interested him, he insists, the historian requires fictive sources. Whether or not the Palmer under consideration played golf remains a mystery--the author has become obscure--he does make his case for fiction as historical authority.

“I have often,” he explains,

“perhaps usually, looked for evidence in novels rather than journals and letters. If a diarist mentions the hour at which he dined, it is probable (whether he provides an explanation or not) that it marks a variation from habit. No novelist can afford to be so casual. If his characters eat at strange times, he must advance reasons to satisfy the reader. If he gives the hour without comment or without the invention of some deranging incident, we may assume that that is the hour customary at the time and in the circles with which we are dealing.” (Palmer 3)

Palmer is too thorough to trust any single novelist. Each requires corroboration: “His details… may be supported by the details in other contemporary novels; and when that happens we may, indeed, feel that we are near to attaining the precision and enviable confidence that mark the most admired historians.” (Palmer 3-4)

Notwithstanding that failsafe, Palmer cannot consider himself authoritative. With a faint echo of the Yale school he declines to overplay his hand and therefore offers his reader a defiant apology of sorts:

“To readers who suffer increasing annoyance from my vagueness, I can only reply that, had pace permitted, I should have been much vaguer and insisted on their company as I picked my painful way over rocks and holes to which, in my mercy, I here seldom allude. Hardly anything in this book is quite, quite true, or would not be the better for qualification.”

The elusive nature of objectivity and dinnertime.

He does not consider the absence of certainty confined to his specific field and confesses that

“ ….a small voice, refusing to be stilled, goes on endlessly whispering to me that history is far from being an exact science; that what appears to be true is, as a rule, only roughly true; and that if one can call two witnesses for every one called by the other side one has done exceptionally well.” (Palmer 3)

“Dinner,” according to David Pocock, “was the major social event of the day in Palmer’s world--a meal which it would be dull to eat alone, a meal for entertainment--and its history and its destiny very much concerned him.” (Pocock xv)

As Pocock indicates, “Palmer noted the movement of dinnertime from 11 a.m. in the reign of Henry VII to 9 p.m. in 1953, the most advanced time yet recorded.” (Pocock xv-xvi) They are not quite right but their timeline is accurate enough so far as it goes.

Although Palmer relies on fiction for his baseline he also cites nonfictional or quasifictional sources, most notably Thomas De Quincey: “Hardly anyone except De Quincey,” he observes, has examined dining customs and times or “looked into their social significance.” (Palmer 5)

Enter the opium eater.

Although he invented the addiction memoir, now associated with freethinking radical outsiders, in the guise of Confessions of an Opium Eater , De Quincey was an extreme reactionary obsessed with aristocracy. “England,” he insists, “owes much of her grandeur to the depth of the aristocratic element in her social composition, when pulling against her strong democracy.” (De Quincey, “English Mail-coach”) His default epithet was ‘Jacobin’ even though he had known hardship. At a destitute seventeen he had spent time homeless, even starving on the streets of London in the company of the fifteen year old prostitute he adored but lost, a source of lifelong yearning and grief. Before then he had mastered both Greek and Latin, which he would put to adroit use throughout his essays. The enormity of his output is, despite the debilitating addiction very nearly inhuman.

De Quincey

Romance, remorse and recrimination.

Later De Quincey would fall hard for another woman and remain faithful to her for the long duration of a marriage that produced eight children. They met while she worked as a charwoman for Wordsworth at the house he shared for a time with an obsessively adoring De Quincey, a most unlikely housemate who ingratiated himself with the Wordsworth family and its hangers on. (James) They fell out because Wordsworth (who may have seduced his own smitten sister Dorothy) and his “coterie of worshipping women” displayed open disdain toward the bride.

In his sweeping historical entertainment The Birth of the Modern Paul Johnson provides the details. Wordsworth had begun to have qualms about his devoted lodger. “Finally,” after a string of scandalous behavior

“De Quincey did the unthinkable: He seduced a local girl, Peggy Simpson, the daughter of a ‘statesman,’ who presented him with a son. The Wordsworth [sic] were particularly sensitive on the point of ‘incomes’ laying their hands on innocent village girls. There had been a celebrated case in 1802 when the maiden known as the Beauty of Buttermere had been deceived by a plausible scoundrel--Coleridge had written eloquently on the subject.” (Johnson 416-17)

It would appear that essayists in particular lusted after inhabitants of the Lake District: “Only a year later Hazlitt had assaulted another local girl, and Wordsworth and Coleridge had been obliged to save him from a mob of angry vigilantes and smuggle him out of the district. Now De Quincey had committed the same unforgivable sin. In his case, it is true, he was prepared to marry the girl and did so.”

That was the honorable thing to do and would have assuaged a more generous crowd. “But,” Johnson continues,

“this marriage made matters worse, if anything. The Wordsworths disapproved of cross-class marriages, at any rate in their own backyard. Besides, Dorothy thought Peggy stupid. When De Quincey had lent Peggy Oliver Goldsmith’s Vicar of Wakefield , she had been disappointed to learn from him that the characters were not real people. Peggy, wrote Dorothy, was a ‘dull, heavy girl… reckoned a dunce at Grasmere School.’ Dorothy and Wordsworth’s wife Mary refused to call on the bride.” (Johnson 417)

Their serial snubs “tormented” De Quincey (James) and whatever his faults we should admire him for that and for choosing her over them. De Quincey set things to right by his lights. “Men of extraordinary genius and force of mind,” he later wrote in general terms, probably including himself, “are far better objects of admiration than as daily companions.” (Marsh) Wordsworth himself resembled “some sort of insect” and De Quincey warned readers to “never describe Wordsworth as equal in pride to Lucifer; no, but if you have occasion to write a life of Lucifer, set it down that… he might be some type of Wordsworth.” (Chiasson; Marsh)

Double addiction.

Books would early become an obsession. In a stark example of the unintended consequence of good intent, a kind bookseller loaned De Quincey the unimaginable sum of seven guineas, unimaginable because De Quincey was only seven and the value of those guineas today amounts to something like a thousand dollars. The generosity set in train a lifelong addiction that mired the bibliomaniac in debilitating debt. (Chiasson) Not that De Quincey cared; “there is,” he explains, “such a thing as buying a thing and yet not paying for it.” (Marsh) No surprise then that De Quincey spent a few stints in debtors’ prison and suffered serial public shaming from his clamoring creditors.

“What money he didn’t spend on laudanum--his preferred opium-alcohol mixture--he spent on buying thousands of books, many of them pricey and rare.” (Dirda) He was, Jamie James says, “a captive of his bibliomania.” One of his biographers, Frances Wilson, adds that the De Quincey family “lived inside what was effectively a warehouse” in which books became “stools, tables, stepping-stones and building blocks.” Things got so bad that at several points De Quincey needed to give up the house for his books and find another place for the family. (James)

Terrible, tyrannous time.

A fantastical perception, and fear, of time linked the addiction of De Quincey to both books and opium. He found that

“time it is upon which the exact and multiplying power of opium chiefly spends its operation. Time becomes infinitely elastic, stretching out to such immeasurable and vanishing termini, that it seems ridiculous to compute the sense of it on waking by expressions commensurate to human life.” (Dickey)

“Time,” he observes in his passage on English dining habits, a passage that appears, incongruously enough, in an essay on ancient Roman foodways, “is a quantity regularly exterminated.” ( quoted at Palmer 64)

“Space,” De Quincey felt, ‘swelled’ around him; time hemorrhaged so that he seemed “to have lived for 70 or 100 years in one night.’” “The great endeavor of his writing,” Dan Chiasson insists with some credibility, therefore “was to convert time, with its irremediable losses, into space, a container where all things can exist simultaneously.”

With a wonderful passage Chiasson delineates the irrational, ingenious and luminous illogic that the conflation created:

“Once he’d bought one book, it was too late; he had, in effect, bought them all, which excused him to buy a second book and then a third. This was the destructive logic behind his opium use: to have started something was to be already too late to stop it, as though a delegate, sent to the future, were messing things up for the innocent De Quincey, back here in the past.”

“It was” in turn, Chiasson continues,

“an insight about time, and also about identity. De Quincey seemed to fear the idea that there were others of him, distributed throughout time and space, acting as his agents without his explicit command.” (Chiasson)

That is trippy enough stuff and the stuff of the nightmares that visited him in tandem with ecstatic and frequently transcendent visions.

Deception and doppelgangers.

Identity of a different sort intrigued De Quincey. He spent a lot of time rewriting the book of a German hack that purported to be the translation of a novel written in English by Sir Walter Scott. The forgery had not, of course, ‘yet’ appeared in English. De Quincey decided to translate it himself but in the process excised long passages from the forgery. He also altered both beginning and end, among many other things, to transform the work of the hack. If the alterations created questions about authorial identity, De Quincey offers a concise enough answer within the book itself. “I would,” he explains,

“ask the reader to consider himself indebted to me for any thing he may find particularly good; and above all things to load my wretched ‘Principal’ with the blame of every thing that is wrong.”

And the solution entails a certain flexibility. “If,” De Quincey says of the reader,

“he comes to any passage he is disposed to think superlatively bad, let him be assured it is not mine. If he changes his opinion about it, I may be disposed to reconsider whether I had not some hand in it.”

If, however, the reader speaks German, De Quincey concedes that “he can judge for himself.” ( quoted at Burwick 58)

He sent his version back to its author and invited him to retranslate the book as an improvement on the original. Predictably enough the German declined to respond. De Quincey’s work was largely useless and although he did review the original for the London Magazine, it was otherwise unremunerative. De Quincey could not help himself. He found the hoax, all hoaxes, delectable and could not resist hoaxing the forger in turn. Small wonder that he slid so far into debt.

Time and space, and questions of identity are not the only dualities that define De Quincey. He divided all writing into “The Literature of Knowledge and the Literature of Power.” Academics struggle to articulate the concept but Michael Dirda offers a sharp explanation. One term is utilitarian, the other transcendental. “‘The Literature of Knowledge’ is inherently provisional and, like any science text or cookbook, open to additions and revision; not so the ‘Literature of Power.’”

De Quincey himself provides examples of the difference, which mirror his preoccupations with the accelerating pace of his times along with romance and antiquity. “A good steam engine is properly superseded by another. But one lovely pastoral valley is not superseded by another, nor a statue of Praxiteles by a statute of Michael Angelo.” ( quoted by Dirda)

In the trail of paradox that is De Quincey, his work does not sit easily in either of his own categories. Instead of improving his locomotive, De Quincey finds different solutions to the same problem in the manner that engineers designed different engines or navies designed the same species of warship in different ways. He obsessively revisited the same subjects. The Confessions generated a number of coda and De Quincey returned to the aesthetics of murder enough times that writers regularly miscite the particular text they attempt to address.

Indelible influence of differing kind.

One of the three greatest Romantic essayists along with William Hazlitt and Charles Lamb, the tiny (under five foot) De Quincey surpassed them both as an eccentric (in Hazlitt’s case quite a feat) and arguably with the sometimes surreal quality of what he called his “impassioned prose.”

Overshadowed now by Hazlitt and Lamb, De Quincey has had the greater impact on other authors. Those who acknowledge an explicit debt range from Baudelaire, Dostoevsky, Gogol, the incomparable James Hogg (whom De Quincey knew), Lovecraft, Poe, Proust and Stevenson to Borges, William Burroughs and Berlioz, who based the Symphonie fantastique on the Confessions . Some critics claim that in his darker, later novels even Dickens succumbs to the seduction of De Quincey. ( see , e.g. , Halliday 65)

Dickens drinks from a time-traveling cup.

“De Quincey,” according to Chiasson,

“is a special case, since he experienced subjective impressions as though they were real…. He witnessed with his senses what some of his contemporaries only pondered in the abstract; opium levelled for him the distinction between actual and imagined things.” (Chiasson)

Against his metaphysical meanderings it may appear incongruous that De Quincey would bother to address something so prosaic as mealtimes but then he addressed pretty much everything, autobiography of course, in several texts following the original Confessions , but also architecture and art (principally Piranesi), biography, those classics and classical antiquity, dueling, economics, fraud, history, hospitality, law, literature, mental illness, German metaphysics, murder, naval warfare, philosophy, piracy, poetry, politics, the postal service, psychology, rhetoric, theology (sigh), style, suicide, usury, veracity and more. In typical style, the discursive “Dinner, Real and Reputed” strays past its purported topic into a number of those subjects.

Economy cures all, or an economist at least offers a way out.

“In the depths of his worst period of his opium addiction” aged twenty six, De Quincey discovered political economy and “the utter feebleness of the main herd of modern economists.” (“History of Economic Thought;” De Quincey, Confessions 1 st ed. 370) He found them

“the very dregs and rinsings of the human intellect; and that any man of sound head, and practiced in wielding logic with a scholastic adroitness, might take up the whole academy of modern economists, and throttle them between heaven and earth with his finger and thumb, or bray their fungus heads to powder with a lady’s fan.”

Then De Quincey read Ricardo and overcame his torpor. The dismal science may appear a strange agent of salvation but much involving De Quincey is strange. “Had this profound work,” he wondered, “really been written in England during the nineteenth century? Was it possible? I supposed thinking had been extinct in England.” (De Quincey, Confessions 1 st ed. 370-71) He became an acolyte and apostle for the doctrine of the great free trader and abolitionist, with the jarring exception of his stance on the Corn Laws, the tariff system on foodstuffs that was Ricardo’s preeminent target. The apparent contradiction is a political accommodation because their repeal harmed the aristocratic landowners De Quincey admired.

Murder multivalent.

Murder became another abiding obsession. What were some of his most famous--nobody reads De Quincey anymore--and subversively funny essays consider the aesthetics and behavioral implications of the crime. They indicate that in his citation to De Quincey, Palmer further indulges a playful side, because in addition to the books and the opium De Quincey was addicted to misdirection.

For once, and unlike his discussion of dinner, he begins at the beginning. “As the inventor of murder, and the father of the art, Cain,” an admiring De Quincey insists, “must have been a man of first-rate genius.” That is not all; the entire family must have been exceptional: “All the Cains were men of genius. Tubal Cain,” according to De Quincey, “invented tubes,… or some such thing,” although due to the fact that during the time of Genesis “every art then was in its infancy…. Even Tubal’s work would probably be little approved at the day in Sheffield.” (De Quincey, “Murder” 8) According to the bible he was the first blacksmith and in De Quincy’s time Sheffield had emerged as a metalworking center so apparently refers to the invention of iron piping.

After so promising a start murder languished in mediocrity for centuries; “it is pitiable to see how it slumbered without improvement for ages.” De Quiney therefore believes himself “obliged to leap over all murders, sacred and profane, as utterly unworthy of notice, until long after the Christian era” which, however, does not deter him from admiring a thwarted classical criminal and speculating that “Cicero… would have howled with panic, if he had heard Cethegus under his bed.”

Cethegus, a young senator burdened by debt, was executed for his part in the Cataline conspiracy but before his demise he botched attempts to murder Cicero and various other worthies. In escaping the knife “the priggism of Cicero robbed his country of the only chance she had for distinction in this line.” De Quincey complains with disdain “that he would have preferred the utile of creeping into a closet, or even into a cloaca , to the honestum of facing the bold artist.” (De Quincey, “Murder” 9) Scatological wordplay from De Quincey--this was after all still the age of Smollett in terms of sensibility, at least to some extent--because by then the Latin for sewer also described primitive genital anatomy.

Philosophy measured by murder, or maybe not.

His consideration of Cicero reminds De Quincey of philosophers more generally; “if a man calls himself a philosopher, and never had his life attempted, rest assured there is nothing in him.” (De Quincey, “Murder” 10-11) And so we are off. De Quincey dispenses with Descartes, who despite his “horrid panic” managed to “show fight” and see off the Dutch sailors who tried to kill him at sea. Had they

“been ‘game,’ we should have no Cartesian philosophy; and how we could have done without that , considering the worlds of books it has produced, I leave to any respectable trunk-maker to declare.” (De Quincey, “Murder” 12)

Though influenced by Descartes, the Dutch “Spinosa” was no ‘inconsiderable rascal’ or ‘craven Friezland hound’ like the murderous sailors, nor was he so inconsiderable as Descartes. And yet by reliable account Spinoza died in his bed undisturbed. “Perhaps,” De Quincey counters, “he did, but he was murdered all the same.” According to De Quincey, again in scatological gear, the philosopher “ate some of the old cock ” on the day he died. It was obvious that the man who recommended the cock, known only as “L.M.,” “smothered him with pillows, the poor man being already half suffocated by his infernal dinner.” (De Quincey, “Murder” 13-14)

The briefest excursion to New York.

De Quincey rules out Lindley Murray as the culprit on the basis that he “saw him at York in 1825,” the year before his death and 148 of them after Spinoza died. Murray it transpires had been so successful a lawyer in New York that he retired at the age of thirty eight and moved to England, where he studied botany, philosophy and theology before writing his English Grammar , a primer that ran to some fifty editions. It dominated pedagogy for decades in both the British Empire and United States.

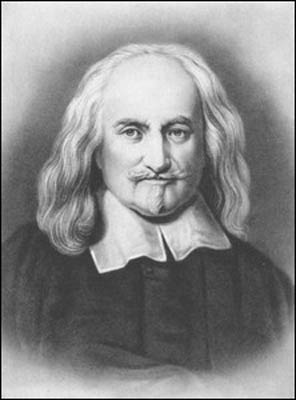

Deserving of death by Leviathan

A cudgel to Leviathan .

De Quincey on Hobbes takes one of the better ironic turns in the history of literate comedy and requires no explication: “Hobbes, but why, or on what principle, I never could understand, was not murdered. This was a capital oversight of the professional men of the seventeenth century,” not because he was any good but because

“he had no right to make the least resistance; for, according to himself, irresistible power creates the very highest species of right, so that it is rebellion of the blackest die to refuse to be murdered, when a competent force appears to murder you.” (De Quincey, “Murder” 14)

At least Hobbes should have been beaten, for

“it is very true that a man deserved a cudgelling for writing Leviathan: and two or three cudgellings for writing a pentameter ending so villainously as--‘terror ubique aderat!’ [terror was everywhere] But no man ever thought him worthy of anything beyond cudgelling.” (De Quincey, “Murder” 15)

Locke, a perennial target of De Quincey notwithstanding his admiration for Ricardo, Locke’s intellectual descendant, also supports the murder theory of genius:

“Locke’s philosophy in particular, I think it an unanswerable objection (if we needed any), that, although he carried his throat about with him in this world for seventy-two years, no man ever condescended to cut it.” (De Quincey, “Murder” 11)

A tear in the fabric of assessment.

About two thirds of the way into the essay, however, its thesis unravels. Not that its failure deters De Quincey from pressing on. He rationalizes the survival of several philosophical stars. “Leibnitz, … one might, a fortiori , have counted on his being murdered, but that was not the case. I believe he was nettled in this neglect, and felt himself insulted by the security in which he passed his days.”

Murder uncommitted or even unattempted, however, may be considered a cause of death. As in horseshoes, getting close may count. “As Leibnitz, though not murdered, may be said to have died, partly of vexation that he was not--Kant, on the other hand,--who had no ambition in that way--had a narrower escape from a murderer that any man we read of, except Des Cartes.” (De Quincey, “Murder” 17) Then again ‘Des Cartes’ was so bad that his verbosities mildew in trunks. In the end, and typical of De Quincey writ large, contradiction and conundrum cascade.

The anomalies and inconsistencies of “Murder” are not inadvertent. The essay is, as Frederick Burwick notes, a running parody of Kant’s theory of aesthetics. The theory, anathema to De Quincey, relies “on pragmatically justified fictions” because “nothing is directly knowable and all knowledge rests on the phenomenological construction of sensory data…. Decisions rest not on absolute facts or truths but on conditional assumptions about experience.” (Burwick 24, 165n2) One person’s murder is another’s art form; another’s accidental death is a murder; Descartes was or was not so bad. Follow that relativist path, De Quincey believes, and peril ensues.

Casuistry and eidoloclasm, or , the art of hoisting a writer on his own petard.

The anomalies and inconsistencies of “Murder” also are consistent with De Quincey’s devotion to casuistry, which he considered “essential to all considerations of right and wrong, good and evil.” (Burwick 25)

De Quincey, who evolved from idolizing to despising Coleridge and Wordsworth, paired casuistry with what he called eidoloclasm, from the ancient Greek “eidolon” for phantom or mirage. Together Frederick Burwick believes they formed the “often malignant counterparts to ‘Knowledge’ and ‘Power,’ but it is not at all apparent that De Quincey considered the concepts that way. His writing includes no indication that either casuistry or eidoloclasm is in any way illegitimate or unfair.

Casuistry is the conceit underlying the adversary system of common law that, to paraphrase Hume, truth derives from argument. Sounding his recurrent concern about the untrammeled acceleration of change, De Quincey himself argues that “as society grows complex, the uses of Casuistry become more urgent.” ( quoted by Burwick 25)

Eidoloclasm is a sort of iconoclasm applied to authors who require cutting down to size. It is not so obscure as at first it appears but rather the mechanism for demonstrating fallibility, failings or even falsehoods in the work of an author by quoting his own language against him. In one of his reviews De Quincey offers an implicit description of the art. “To be an eidoloclast,” he warns,

“is not a pleasant office, because an invidious one. Whenever that can be effected, therefore, it is prudent to decline the odium of such an office upon the idol himself. Let the object of false worship always, if possible, be made his own eidoloclast.” ( quoted by Burwick 26)

In practice the task is not so tough when an author’s own writing reveals that his reputation is undeserved, a mere mirage foisted on the public.

By means of casuistry and eidoloclasm, De Quincey boasted that he had become “ doctor seraphacus , and also inexpugnabilis upon quillets of logic.” ( quoted by Burwick 24) A quillet is one of several small tracts of land that combine to form a large one. So he considered himself, in loose translation, a literary arsonist wielding unassailable argument based on incremental evidence. That describes the exceptional trial lawyer that was De Quincey in literary terms.

Respectability and the slippery slope.

Murder artistically committed, while aesthetically exceptional, requires an artist as accomplished as Cain and therefore is neither recommended to the general populace nor prerequisite to a respectable reputation:

“Believe me, it is not necessary to a man’s respectability that he should commit a murder. Many a man has passed through life most respectably, without attempting any species of homicide--good, bad, or indifferent. It is your first duty to ask yourself, quid valeant humeri, quid ferre recusant? We cannot all be brilliant men in this life. And it is for your interest to be contented rather with a humble station well filled, than to shock everybody with failures, the more conspicuous by contrast with the ostentation of their promises.”

Murder is in artistic terms a tough assignment. In a subsequent essay on the subject, De Quincey warns the aspirant practitioner that much can go wrong:

“Awkward disturbances will arise; people will not submit to having their throats cut quietly; they will run, they will kick, they will bite; and whilst the portrait-painter often has to complain of too much torpor in his subject, the artist in our line is generally embarrassed by too much animation.”

Nor is the choice of subject or setting as straightforward as it may seem.

“Something more goes to the composition of a fine murder than two blockheads to kill and be killed, a knife, a purse, and a dark lane. Design,… grouping, light and shade, poetry, sentiment, are now deemed indispensable to attempts of this nature.” ( quoted by Dirda)

The aspirant artist was after all living in the Romantic era.

A person of ordinary artistic ability runs the extreme risk of “making a fool of himself by attempting what is as much beyond his capacity as an epic poem.” Besides, even the most principled practitioner of the art requires a deep reservoir of discipline if he is to forestall any number of unfortunate habits.

“For if once a man indulges himself in murder, very soon he comes to think little of robbing; and from robbing he comes next to drinking and Sabbath-breaking, and from that to incivility and procrastination. Once begun upon this downward path, you never know where you are to stop. Many a man has dated his ruin from some murder or other that perhaps he thought little of at the time.” (Morrison 235; The passage is as often misattributed to the wrong essay as it is quoted, a rare instance of attention paid to De Quincey and a common one of slovenly practice that results from reliance on secondary sources instead of the original.)

De Quincey does not spare himself the satire; though “exceptionally courtly in his manner and speech,” he himself was notorious for incivility, fell out with his editors and indulged in procrastination sufficiently severe that he lost position editing the Westmoreland Gazette , a prestigious Tory journal that, under De Quincey’s control, specialized in the scurrilous. (Dirda; Halliday 65)

Hanging out, De Quincey style.

Dinner… or not.

Despite its title De Quincey begins ‘Dinner’ by delving into the vexed question of breakfast, or the historical absence of it, which itself requires comparing global economics Roman and Romantic. His analysis might be anchored in the twenty first rather than nineteenth century because, among other things, of its description of the earth as generous (up to a point) with its finite but malleable resources. “It is an important fact,” until lately often overlooked in our own times,

“that this planet on which we live, this little industrious earth of ours, has developed her wealth by slow stages of increase. She was far from being the rich little globe in Caesar’s days than she is at present.”(De Quincey, “Dinner” 1)

The world in De Quincey’s days was for the most part preindustrial, so his analysis skews agricultural. “The earth in our days is incalculably richer, as a whole,” De Quincey reasons,

“than in the time of Charlemagne: at that time she was richer, by many a million of acres, than in the era of Augustus. In that Augustan era we descry a clear belt of cultivation, averaging about six hundred miles in depth, running in a ring-fence about the Mediterranean. This belt, and no more , was in decent cultivation…. At present what a difference! We have that very belt, but much richer, all things considered aequatis aequandas , than in the Roman era.” (‘Dinner’ 1-2)

Earth elects to budget.

In consequence “our mother, the earth, being (as a whole) so incomparably poorer, could not in the Pagan era support the expense of maintaining great empires in cold latitudes.” Nor could she afford candles and

“would certainly have shuddered to hear any of her nations asking for candles. ‘Candles!’ She would have said, ‘Who ever heard of such a thing? And with so much excellent daylight running to waste, as I have provided gratis ! What will the wretches want next’?”

Apparently, although they did not know it, they wanted tobacco, which Earth also refused. “In this point,” De Quincey complains, “we must tax our mother earth with being really too stingy.” Not so the candles; to the contrary, “we approve of her parsimony. Much mischief is brewed by candle-light. But it was coming on too strong to allow no tobacco.” And so, denied light to read or plot and tobacco to smoke after dinner (whenever and whatever that may have been; De Quincey is ambiguous), the honest Roman went to bed at sunset. (“Dinner” 2)

That assertion amounts to more misdirection, or at least advocacy by omission, presumably a fair tactic in the context of casuistry. De Quincey is right to observe that darkness enables underhand activities, and the Romans understood the same thing. Latin has specific words that refer to dwellers in the dark as debauched or criminal by nature, and unlike his daytime counterpart a nocturnal thief was liable to be killed on sight by any citizen. (Ker 219)

Romans, however, recognized a countervailing concept, and Latin has a word for it. Student that he was of classical antiquity, De Quincey would have been conversant with the concept of lucubratio, or writing by lamplight, from lucubrum, a small lamp that required little fuel. (Ker 217, 217n33) In part lucubratio was a practical tool for the industrious Roman writer with daytime demands on his time. According to Quintilian “working by lamplight when we come to it fresh and rested, gives the best kind of privacy.” (Ker 214)

It also could be a signal of virtue, “a spectacular emblem of household productivity…. Nocturnal labor--that is, lucubration--is the height of frugality. Being conducted by the light of a moderate lamp, it conjures up time for labor where there was none…. ” (Ker 225, 217) Seneca and Pliny the Elder also address the concept so it is not obscure.

Trouble at breakfasttime.

De Quincey gets so exercised on the subject that he becomes unclear, but the poverty of earthly wealth along with the putative poverty of nightlife apparently combined to deny ancients the wit to comprehend breakfast. Instead they suffered the “very Barmecide feast,” a literal mouthful of “thrice cursed biscuit, with half of fig, perhaps, by way of garnish,” taken with haste on the fly in a carriage, or sedan chair, or on foot, “fit,” he laments, only “for idolatrous dogs like your Greeks and Romans” who in fact he admired. But their uncivilized ignorance of breakfast was beyond toleration.

“You, reader,” De Quincey is confident, therefore

“will breathe a malediction on the classical era, and thank your stars for making you a Romanticist. Every morning we thank ours for keeping us back, and reserving us to an age in which breakfast had been already invented…. No such genius had yet arisen in Rome. Breakfast was not suspected. No prophecy, no type of breakfast had been published. In fact, it took as much time and research to arrive at that great discovery as at the Copernican system.” (De Quincey, “Dinner” 5, 2, 3)

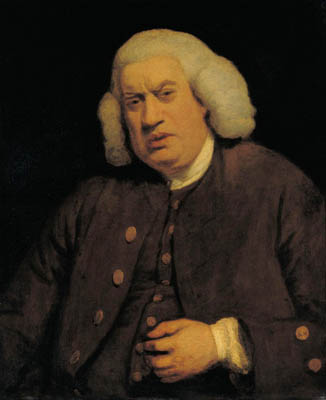

Bloom is not the only figure under consideration to address the odious Dr. Johnson. A sustained attack on dictionaries and by implication Johnson runs as a ribbon through ‘Dinner’ because “dictionaries, one and all, are dull deceivers,” and have done much to muddy the historical misunderstanding of breakfast or its absence. (De Quincey, “Dinner” 3)

No trouble with tiffin.

Dictionaries do not shoulder all blame for the chaos attendant upon dinner. The English themselves and their habits have seen to that, although dictionaries have done their worst to create confusion. De Quincey is blatant in his unreliability here, insisting that although dictionaries translate prandium, which means something like a late breakfast or early lunch, as dinner, the Latin term really means “moonshine.” De Quincey declares in definitive mode that moonshine “as little soils the hands as it oppresses the stomach.”

Moonshine paired with its mistranslation triggers consideration of tiffin and the lack of any western equivalent. “The English corresponding term is luncheon: but how meagre a shadow is the European meal to its Asiatic cousin!” Still, “gloriously as tiffin shines,” nobody must mistake it for dinner. (De Quincey, “Dinner” 6)

Dinner forges ahead.

Returning to the English and their dinner, or dinners, De Quincey traces their evolution across more than three centuries. He finds that “both in England and in France, dinner has travelled, like the hand of a clock, through every hour between ten, A.M. and ten, P.M.”

Rosemary Hill identifies an unanticipated effect of the journey on English usage. As “meals themselves and their relative importance in the pattern of the day… shifted over time” the “distinction between ‘dinner’, taken in the afternoon, and ‘supper’, the last, usually light, meal of the day, fades in the 19th century as dinner moves later.” (Hill)

Fad and fashion had buffeted the sovereign dining habits that exerted outsize influence on elites over the years. “We have a list, well attested,” claims De Quincey, “of every successive hour between these limits having been the known established hour for the royal dinner-table within the last three hundred and fifty years.” (De Quincey, “Dinner” 7)

Henry VII of England had dined at eleven a.m. during the sixteenth century but by the 1640s Cromwell ate his dinner two hours later. By the Glorious Revolution of 1688 dinner for the better sort (and for the most but not entire part De Quincey deals with the better sort) appeared on the table at two. A scant fifty odd years on, in the midst of the Jacobite Rebellion, “people (but observe, very great people) advance to four, P.M.” De Quincey then notes that at about the same time “Pope,” apparently not so great, “complains to a friend… of dining so late as four” and refuses future invitations from the fashionable hostess. (De Quincey, “Dinner” 15)

In his Dictionary of the English Language Dr. Johnson betrays his constantly conservative cast of mind. Writing in 1755, he asserts that “DINNER” is “the chief meal; the meal eaten about the middle of the day,”, that is, around noon. “Nowadays” however, as Giovanni Iamartino notes, that is “referred to as lunch. ” (emphasis in original)

Unless he is simply mistaken, Dr. Johnson must refer to dinner for those less prosperous than his peers in the middle classes. “For the affluent middle classes with whom Johnson associated,” Iamartino again, “dinner was at 5 or 6 in the afternoon.”

Elsewhere Iamartino is something of an outlier in terms of the historical timeline. “It was,” he claims, “only towards the end of the eighteenth century that dinner was moved to around 2 PM and supper to 8 PM.” (Iamartino 19) Iamartino discloses no citation and no other source supports that retrograde transition.

Dr. Johnson defines “SUPPER” as “the last meal of the day, the evening repast” except that for him it was not. According to Boswell, Johnson “seldom took supper,” further indication that the Dictionary does not necessarily report on his own practices and those of his milieu. Johnson himself supports the inference. “I believe,” he explains, “it is best to eat just as one is hungry; but a man who is in business, or a man who has a family, must have stated meals. I am,” he adds, “a straggler.” (Iamartino 22)

A twenty first century scholar tries her hand.

Sarah Moss offers a less nuanced and transitory description of Romantic dinnertimes, but then she cites neither De Quincey nor Palmer, or Pocock for that matter. She does, however, recognize along with them the freighted social signals that encumber timing. “Readers of eighteenth-century fiction,” she observes, “know the charged atmosphere surrounding the timing of meals” and she is right.

Moss also is right about the timing as far as she goes but does not go far enough in terms of detail:

“Dinner began--and for some people remains--as a midday meal. By the 1750s, diners among the elite in London were served around 4 p.m., with an informal supper usually composed of left-overs from dinner provided before bedtime. Working people and those outside London dined earlier, but there is a continuum between status and dining hour, so that even in the provinces and among the middling sort, formal and celebratory meals took place later than ordinary dinners. By the 1820s, the gentry were dining at 8 and 9 p.m., which made supper redundant except at the end of a ball or late party in the early hours of the morning, and created a vacancy which was filled by what became ‘lunch.’” (Moss 12)

Turn to De Quincey, Palmer and Pocock instead for the entire tale.

Sources:

Jad Adams, “The English Opium Eater by Robert Morrison,” The Guardian (8 January 2010)

Anon., “Apperception,” AlleyDog.com , https://www.alleydog.com/glossary/definition.php?term=Apperception (n.d.) (accessed 13 February 2023)

Anon., “Last name: Somers,” SurnameDB , https://www.surnamedb.com/Surname/Somers (n.d.) (accessed 27 March 2023)

Anon., “Maria Edgeworth,” The Maria Edgeworth Centre , www.mariaedgeworthcentre.com (n.d.) (accessed 28 March 2023)

Anon., “thing,” The Chicago School of Media Theory ,

https://lucian.uchicago.edu/blogs/mediateory/keywords/thing/ (n.d.) (accessed 22 November 2022)

Anon., “Thing Theory in Literary Studies,” Stanford Humanities Center: Arcade ,

https://shc.stanford.edu/arcade/colloquies/thing-theory-literary-studies (“updated”) (accessed 22 November 2022)

Anon., “Thomas De Quincey, 1785-1859,” The History of Economic Thought , Institute for New Economic Thinking, http://www.hetwebsite.net/het/profiles/quincey.htm (n.d.) (accessed 13 December 2022)

Phil Baker, “Guilty Thing by Frances Wilson review--a superb biography of Thomas De Quincey,”

The Guardian (23 April 2016)

Eric Banks, “Land of the Nod,” Bookforum (Sept/Oct/Nov 2016)

Maxine Berg, Luxury and Pleasure in Eighteenth Century Britain (Oxford 2005)

Tim Blanning, The Romantic Revolution (London 2010)

George Clement Boase, “Kitchiner, William, M.D.,” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 1885-1900 , https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Dictionary-of-National-Biography,-1885-1900/Kitchiner,-William (n.d.) (accessed 21 February 2023)

Fernand Braudel, Civilization and Capitalism , 3 vol.s under separate subtitles (Berkeley 1979)

Tom Bridge & Colin Cooper English, Dr. William Kitchiner Regency Eccentric Author of the Cook’s

Oracle (Lewes Sussex 1992)

Bill Brown (ed.), Things (Chicago 2004)

Jo Buddle, “An eccentric epicurean: the life of William Kitchiner (1777-1827), The Cookbook of Unknown Ladies , https:// lostcookbook.wordpress.com/2013/06/11/eccentric-epicurea n/ (6 November 2013) (accessed 5 February 2023)

Frederick Burwick, Thomas De Quincey: Knowledge and Power (New York 2001)

Marilyn Butler, Maria Edgeworth: a literary biography (Oxford 1972)

Colin Campbell, “The Tyranny of the Yale Critics,” The New York Times Magazine (9 February 1986)

Dan Chiasson, “Hell of a Drug,” The New Yorker (17 October 2016)

Claire Connolly, “Maria Edgeworth was a great literary celeb. Why has she been forgotten?” The Irish Times (26 January 2019)

Theodore Dalrymple, “His gastronomical practice,” British Medical Journal vol. 345 no. 7869 (11 August 2012) 35

Elspeth Davies, Dr Kitchiner and the Cook’s Oracle (Durham 1992)

Tristan de Lancey et al , Strata: William Smith’s Geological Maps (London 2020)

Thomas De Quincey, “On Murder, Considered as an Art Form,” (North Haven CT 28 November 2022; orig. publ. 1827)

“Dinner, Real and Reputed,” http://www.authorama.com/miscellaneous- essays-6.html (accessed 1 December 2022); orig. publ. Blackwoods no. xlvi (December 1839)

Colin Dickey, “The Addicted Life of Thomas De Quincey: Chasing the dragon into a new literary realm,” Lapham’s Quarterly (19 March 2013)

Michael Dirda, “The fascinating life of an English writer, essayist and ‘opium eater,’” The Washington Post (30 December 2010)

Bonamy Dobree, English Essayists (London 1964)

Kenneth Forward, “‘Libellous Attack’ on De Quincey,” PMLA vol. 52 no. 1 (March 1937) 244-60

Neil Edmund Bain Halliday, “Fatal Consequences: Romantic Confessional Writing of the 1820s,”

unpbl. PhD thesis (Univ. Birmingham October 2019)

Daisy Hay, Dinner With Joseph Johnson (Princeton 2022)

Rosemary Hill, “Spaghetti Whiplash,” London Review of Books (17 November 2022)

Richard Holmes, The Age of Wonder (New York 2010)

Giovanni Iamartino, “At table with Dr Johnson: food for the body, nourishment for the mind,” in Francesca Orestano & Michael Vickers (ed.s), Not just Porridge: English Literati at Table (Oxford 2017) 17-34

Jamie James, “Eating Opium and Writing Intoxicating Prose,” The Wall Street Journal (28 October 2016)

William Jerdan, Men I Have Known (London 1866)

Paul Johnson, The Birth of the Modern (New York 1991)

Heidi Kaufman & Chris Fauske (ed.s), An Uncomfortable Authority: Maria Edgeworth and Her Contexts (Newark DE 2004)

Edwina Keown, “Edgeworth, Maria,” Dictionary of Irish Biography , http://www.dib.ie/biography/edgeworth-maria-a2882 (n.d.) (accessed 27 March 2023)

James Ker, “Nocturnal Writers in Imperial Rome: The Culture of Lucubratio,” Classical Philology vol 99 no 3 (July 2004) 209-42

William Kitchiner, The Cook’s Oracle (London 1817)

David Knight, “Davy, Sir Humphrey, baronet (1778-1829),” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford 2004)

Gilly Lehmann, The British Housewife: Cookery Books, Cooking and Society in 18 th -Century Britain (Totnes, Devon 2003)

John Gibson Lockhart, “The Leg of Mutton School of Prose. No. I. The Cook’s Oracle ,

Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine vol. X (August-December 1821) 563-69

(writing as ‘Peter Morris’), Peter’s Letters to His Kinsfolk , 3 vol.s (Edinburgh 1819)

Robert Morrison The English Opium-Eater: A Biography of Thomas De Quincey (New York 2012)

The Regency Years (New York 2019)

(ed.) Thomas De Quincey: Selected Writings (Oxford 2022)

Sarah Moss, Spilling the beans: eating, cooking, reading and writing in British women’s fiction, 1770-1830 , (Manchester Lancs 200)

Christopher Ott, The Evolution of Perception and the Cosmology of Substance (Bloomington IN 2004)

Valerie Pakenham, “Introduction,” Maria Edgeworth’s Letters from Ireland (Dublin 2017; Kindle edn. N.p.)

Arnold Palmer, Movable Feasts (Oxford 1952)

Blake Perkins, “An Enquiry into the Derivation of Chowder,” Petits Propos Culinaires no. 109 (September 2017) 32-67

“London Taverns and the Dawn of the Restaurant Age,” Petits Propos Culinaires 121 (November 2021) 85-109

Diane Purkiss, English Food: A People’s History (London 2022)

Brian Rejack, Gluttons and Gourmands: British Romanticism and the Aesthetics of Gastronomy,

unpubl. dissertation, Vanderbilt University (Nashville 2009)

G. J. Renier, The English: Are They Human? (London 1931)

Lee Sandlin, “Seductively Dangerous: Without Thomas De Quincey there would have been no James Frey,” The Wall Street Journal (11 December 2010)

Robert McG. Thomas, “René Wellek, 92, a Professor of Comparative Literature, Dies,” The New< York Times (16 November 1995)

Jenny Uglow, “The Reader of Rocks,” The New York Review of Books (11 March 2021)

Sarah Wasserman, “Thing Theory,” Oxford Bibliographies , https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/view/document/obo-9780190221911/obo-9780190221911-0097.xml (24 June 2020) (accessed 22 November 2022)

Frances Wilson, Guilty Thing: A Life of Thomas De Quincey (New York 2016)

Simon Winchester, The Map that Changed the World (New York 2009)