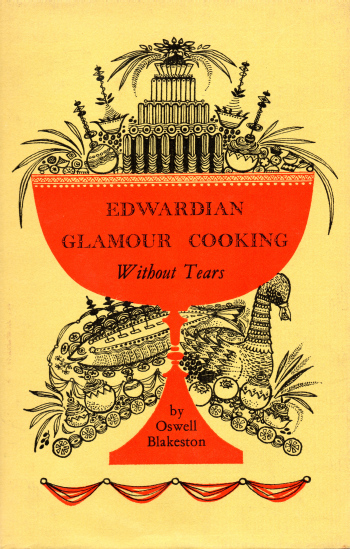

A review of Edwardian Glamour Cooking (Without Tears)

by Oswell Blakeston

Despite its title, this little book is not a tie-in to either True Blood or Twilight. Nor is it quite the book it claims to be, for Edwardian Glamour Cooking is fixated, not on the foodways of Edwardian Britain in any comprehensive sense, but rather on the mortar and pestle. Then again nobody else has shown much interest in Edwardian cooking over the last century, let alone written a monograph on the subject. The book therefore incites a preliminary giggle with its assumption that mid-century readers clamored “to reproduce the glamour of Edwardian cookery.” (Glamour 9)

The actual author of our book, Henry Joseph Hasslacher, made two films, I Do Like to Be By the Seaside in 1929 and, in 1930, “one of the first abstract films in England,” Light Rhythms. Between the wars he also edited two magazines, “the small yet influential film magazine” Close Up, and the poetry review Seed with Herbert Jones. Hasslacher also contributed poetry and criticism to a number of periodicals and wrote some 39 moderately successful books ranging from detective fiction and poetry to novels “that,” according to wikipedia (but caveat emptor), “mix gay themes with suspense and detective plots.” He also wrote or co-wrote books on film and photography. Other titles, seven of them, covered travel and cookery; ‘Oswell Blakeston,’ taken from Osbert Sitwell, a writer he admired, and his mother’s maiden name of Blakiston, is one of his several pseudonyms.

His devoted companion Max Chapman, “uncompromising on his pacifism and his homosexuality,” said that ‘Blakeston’ “had a quick eye for the bizarre and the outrageous.” (Independent) He had run away from school to become a conjuror’s assistant before finding his way into the early film industry and establishing that lifelong career as journalist, critic and author. John Betjeman considered Blakeston “a neglected genius of the macabre” but it is a humane playfulness that permeates Edwardian Glamour Cooking. (Independent)

Blakeston obviously was something of a prankster, and based on some of his other titles, which include For Crying Out Shroud, What the Dino-saur and Zoo Keeps Who?, we might suspect that Edwardian Glam is a parody. That, however, would be a mistake. The tone is instructive, the recipes are presented with clarity in a uniform format (in contrast to, say, Elizabeth David’s)--and they work.

Which is not to say that Glamour is a conventional, let alone mainstream, publication. In common with all of Hasslacher’s other work, it was published (in London during 1960) by a tiny press, in its case Hugh Evelyn Limited, and remains long out of print. The text runs to barely 53 illustrated pages, but there is value here, and it would be unthinkable to accuse Hasslacher/Blakeston of stinting his subject or padding the book.

Which is not to say that Glamour is a conventional, let alone mainstream, publication. In common with all of Hasslacher’s other work, it was published (in London during 1960) by a tiny press, in its case Hugh Evelyn Limited, and remains long out of print. The text runs to barely 53 illustrated pages, but there is value here, and it would be unthinkable to accuse Hasslacher/Blakeston of stinting his subject or padding the book.

Its cast is monomaniacal. If a dish cannot be developed by means of ‘The Technique’ then it has been abandoned, with one exception; Blakeston makes reference to “grilled meats and fish” (no recipes) but only to introduce his excellent compound butters, which he includes on the pretext that often “they are used by chefs to give a last touch to a sauce,” itself sometimes a component of his glamorous concoctions. (Glamour 46)

‘The Technique’ itself basically consists of minor variations on pulverization and steaming. Originally the task required a mortar and pestle and, in some cases, what Blakeston calls a “mincing machine,” or meat grinder, but he concedes that following the advent of electrical power in the kitchen his readers “probably will use an electric mixer;” fifty years on he could have added a food processor to our equipment. (Glamour 10)

Acolytes of glamour will need something else as well: “the Edwardian technique of pounding, which we are considering, generally demands the use of moulds--and they should be welcomed.” (Glamour 11) Blakeston is rhapsodic on the subject, for

“a mould can give a fantastically different appearance to a main dish. It introduces the aesthetic dimension, and it need not be an expensive item. The most exciting ones can be picked up in antique shops at bargain prices.... One may acquire an elaboration of towers and minarets and domes, sufficient to dazzle the eye of all beholders.” (Glamour 11)

If, however, you are bereft of architectonica, at least momentarily, weep not; Edwardian Glamour Cooking is still for you:

“While you are building up your collection of moulds--grandiose architectural affairs and ones which produce fish shapes like mermaids and birds like dreams--you can, using the technique, console yourself with dishes which do not call for moulds....The ingenious, too, will be able to prepare surprises by pressing into service ramakins [sic] and scallop shells and similar receptacles that may be to hand.” (Glamour 12)

Decoration and “the Edwardian love of garnish for garnish’s sake” drive Blakeston to similar ecstasies, and he includes a range of practical suggestions along with his flights of phantasm for, after all, “[t]his is essentially a practical book.” (Glamour 14, 9) An example of sound advice, never violated by the Editor, is Blakeston’s warning not to “plunge into an Edwardian party without making at least one try-out in the family circle.” As he explains,

“[o]ne try-out should provide a yard-stick of quantity and appetite for the confection that will start conversation flowing and recall the wisteria-embowered tables of Edwardian elegance and retell the anecdotes that sparkle in biographies.” (Glamour 15)

Quantity is the only variable that requires a test run because, unlike ordinary cookbooks, Edwardian Glamour offers “a repertoire of party dishes which are at one and the same spectacular and foolproof--spectacular because they are intended to delight the eye as well as the palate, and foolproof because the methods used in their preparation eliminate the normal hazards of tough meat and over-cooking.” Glamour 9)

Precisely what, as the English say, is on offer to ensure the outcome? For starters, lots of ground meat. Edwardian glamour food may be spectacular but in most of the manifestations chronicled by Blakeston it most certainly, and appropriately enough for these straitened times, is cheap. More expensive items like crab, lobster, partridge or pheasant share their castellated compartments with cream, eggs, gelatine, vegetables; sauces, “SUPREME” (aka ‘white’) and brown round things out.

A festive if not wisterial dinner might start with Alexandra Sardines (from the sea via the can) followed by the essential Edwardian soup course of, say, a grand tureen of (ground) beef and kidney. The main event might be a timbale of minced but turreted beef, Lamb Lucullus, a salmon mousseline (a pound of fish stretches, christlike, to feed six) or any number of soufflés “made with all sorts of meat and fish and cheese.” (Glamour 45) For dessert, well, Blakeston is not big on desserts and does not include any, but there are sauces and sandwiches, potted foods, aspics of course, compound butters (the chutney is intriguing) and forcemeats too.

All of this may sound a little ridiculous, but the recipes are foolproof as advertised; for the most part you mash everything together and stick it in a mold to steam on the stove or bake in a bain-marie. As illustrations of lavishly wobbling Edwardian banquets attest, it is, as Blakeston claims, “the food of kings in the days when kings abounded;” some of the results even taste good. (Glamour 11)

Recipes for glamorous anchovy and olive sandwiches, chutney butter, Lamb Lucullus, and brown and Madeira sauces appear in the practical.

Sources.

Oswell Blakeston, Edwardian Glamour Cooking (Without Tears) (London 1960)

David Buckman, “Obituary: Max Chapman,” The Independent (30 November 1999)

Wikipedia.com, “Oswell Blakeston”

www.lib.utexas.edu/taro/uthrc/00014hrc-00014.html, “Oswell Blakeston: An inventory of his papers at the Harry Ransom Research Center”