Notes on the state of Virginia foodways in the early national period.

1. A practical approach to the past.

Fifty years ago, the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation published a book of some scholarly ambition that probably did not reach a wide audience. It is Colonial Virginia Cookery by Jane Carson, who has drifted into obscurity.

Despite her somewhat academic bent, Carson aimed her book at an audience of amateur enthusiasts rather than university professors in conformity with the policy of Williamsburg itself. They would, however, be rigorous reenactors rather than casual cooks. Instead of joining her peers and descendants in the cookbook business to adapt eighteenth century recipes for twentieth century kitchens and techniques, she sticks to her sources and their open fires, ovens and implements.

Also in common with the original intent of Williamsburg, Carson set out in the Colonial Heroic Idiom:

“Readers interested in how colonial housewives managed to serve the elaborate meals that tradition ascribes to them must consult the original sources. Collectors of antique cooking equipment, too, want to know how all the pieces were used and how to arrange them in a working colonial kitchen.”

Colonial Virginia Cookery does not attempt to address the foods of anything like a social cross-section, but rather to revive the foods of the rich which, after all, are the interesting foods from the past. In further defense of the project, the expensive ingredients that once expressed social rank do not cost so much any more. Most of them also are accessible to culinary genealogists and reenactors.

“It is to these antiquarians and collectors,” perhaps the cohort most despised by serious historians, that Carson addressed her “study of the procedures in colonial cooking.” (Carson ix) That audience accounts for its limitations but even so, Colonial Virginia Cookery is a useful historical artifact that succeeds to a limited extent on its terms, although a novice to the openfire kitchen cohort will not find basic guidance.

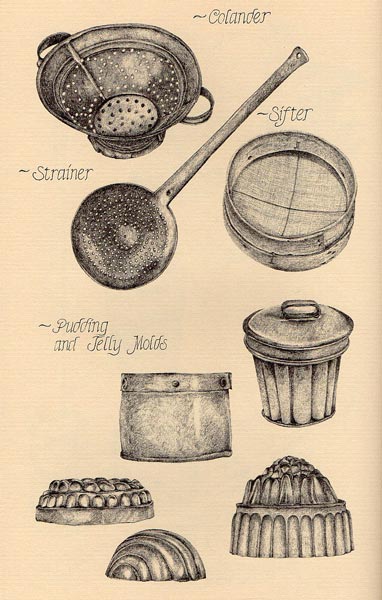

Carson does offer her reader a chapter that describes in detail eighteenth century kitchen equipment--the section of drawings is lovely in its Colonial Revival sensibility--and follows it with others on the basic methods of boiling and stewing; roasting, broiling and frying; and baking, followed by a chapter covering sauces, garnishes and made dishes.

Her approach is honest; Carson describes her English and Virginian sources in turn and why she selected them: “The most popular English cookbooks in Virginia” during the eighteenth century “were Mrs. Smith’s, Mrs. Glasse’s, Mrs. Harrison’s, Mrs. Raffald’s, and Mrs. Bradley’s.” (Carson xii)

2. But what past?

As for recipes written or printed in Virginia, Carson found but two sources and neglected to explicate or determine the antecedents of either one. They are problematic. The first, the Frances Parke Custis manuscript, would appear in print during 1940 as The Martha Washington Cook Book and again with an introduction by Karen Hess in 1981 as Martha Washington’s Booke of Cookery. Although Carson admits she does “not recognize the recipes,” she also maintains without equivocation that “[t]hey are all English” and concludes that they were “copied from a printed seventeenth century cookbook.” (Carson xviii) A trawl through seventeenth century printed sources should have identified their origin.

Karen Hess concurs in dating the Washington recipes to the seventeenth century. In fact she surmises that it dates to 1650 or earlier. (Hess, Booke of Cookery 462) The century itself ended seven decades before American independence, and if Hess is right then Carson has no basis to assume that the recipes reflect eighteenth century practice in Virginia or anywhere else in British North America. “By the time the manuscript came into the hands of Martha Custis in 1749,” Hess thinks,

“it had long since become a family heirloom and that it had not served as a working kitchen manual since the beginning of the century, perhaps earlier. Many of the recipes must have seemed old-fashioned to Martha, and they became increasingly so as time went on; the cuisine of the manuscript is that of Elizabethan and Jacobean England.”

Hess adds that the “cuisine of Hannah Glasse,” which she outlined in The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy, “seems very modern compared to that of our manuscript.” (Hess, Booke of Cookery 7) It was the bestselling cookbook of all among Virginians during the second half of the eighteenth century.

None of this establishes that the manuscript does not reflect foodways in eighteenth century Virginia but without a close reading of subsequent sources, which Carson does not supply, nothing connects it to them either.

The primary source of recipes Carson casts as typical of the eighteenth century is The Virginia House-wife by Mary Randolph. It was the first cookbook written by an American published in the south and only the second by an American published anywhere.

As such it becomes apparent that her chosen title, dictated perhaps by the requirements of Colonial Williamsburg, is slightly off. While the English publications and Custis manuscript predate 1775, her principal source for the explication of Virginia foodways did not appear until 1824. Even accounting for the theoretical lag between culinary practice and cookbook publication, five decades is a long time.

3. The elusive eighteenth century.

Carson, Hess and subsequent commentators, however, claim extenuating circumstances in terms of time. Carson explains that Mrs. Randolph ran “a series of boardinghouses” and also, as the title of her book infers, “was a Virginia housewife.” More important for Carson’s purposes, Mrs. Randolph “was reputed to be the best cook in Richmond” during the middle of the 1790s. (Carson xix)

Carson quotes a passage from The Virginia House-wife that contends its recipes “were written from memory, where they were impressed by long continued practice.” From this alone, Carson takes the leap to conclude that reputation coupled with a good memory “guarantees them today as the best culinary practice in her Virginia.” (Carson xx-xxi)Neither reputation nor memory, however, guarantees anything.

Lovely Colonial Revival style illustrations.

Citing no source and providing no reason for her assertion, Hess says in similar vein that “Mrs. Randolph’s heyday was the 1790s and there is reason to believe that the cuisine she records dates to that time,” which anyway is postcolonial. (Hess, Booke of Cookery 6) In fact there is no documented reason to believe The Virginia House-wife was exclusively retrograde and good reason to believe the contrary. A book that records past practice but offers nothing au courant is unlikely to find a market, and the House-wife was a bestseller.

Hess nearly contradicts herself at a number of junctures in her placement of the Randolph recipes. “In the richly worked tapestry of Virginia,” she observes,

“the warp was English, as surely if not so plainly as in that of New England. And there are English recipes by the score in The Virginia House-wife, any number of which are virtually identical to their parallel recipes from Elizabethan and Jacobean times as they are found in Martha Washington’s Booke of Cookery,”

citing some twenty or so examples. (Hess, Virginia House-wife xxiv, xxv) Perhaps, then, the two sources, despite their origins nearly two centuries apart, do present a good picture of the eighteenth century Virginia kitchen even though neither dates to the century itself.

If, however, Glasse appears modern compared with the Custis manuscript, the cooking of Randolph in turn is “finer and more imaginative,” by inference more modern, “than that of Hannah Glasse, even as it shows the imprint of the older book” but not that much older if many of the the Randolph recipes date to the seventeenth century. (Hess, Booke of Cookery 7) Or is it eighteenth century? The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy first appeared in 1747.

Unfortunately neither Carson nor Hess attempts to determine which of the recipes originate after 1775 or the 1790s for that matter. Some of them do. Seventeen use tomatoes which, on the North American mainland, “were not widely cultivated until after 1830.” (Cutler 8) Only a single extant kitchen manuscript from eighteenth century British North America even refers to the tomato and it was written in South Carolina. One of Mrs. Randolph’s recipes, for tomato ketchup, is the first to appear in print in any language anywhere, although to be fair Hess considers a “tomata sauce” from an 1814 or 1817 New York edition (she is unclear) of Mrs. Rundell’s New System of Domestic Cookery “effectively a catsup.” (Smith 27; Hess, Virginia House-wife xx)

Not around much until after 1830.

These infirmities do not quite disqualify Mrs. Randolph as an eighteenth century source, but citation to her book requires a duty of care that neither Carson nor Hess has met.

The staff at Historic Foodways, the culinary website of Colonial Williamsburg, has anticipated or perhaps responded (it is not clear) to concern about the late publication date of The Virginia House-wife. In “Why Mary Randolph?” a staffer maintains that Mrs. Randolph was 62 when she wrote it; based the book “on a solid foundation of cookery learned as a younger woman;” and plagiarized some eighteenth century sources.

None of this provides much satisfaction. Historic Foodways compounds the problem by claiming a number of Randolph recipes featuring tomatoes for colonial Virginia and rationalizing the use of Mrs. Randolph as a source because “The Virginia House-wife offers something unique--It is also Virginian.” (Costa) So is the food at The Roosevelt in Richmond: It opened in 2011.

4. Artificial antecedents and influences.

Notwithstanding her reputation for irascible rigor, Hess makes some unwarranted assumptions during the course of her analysis of the Randolph text. Although garlic was hardly unknown in the contemporary English kitchen, she claims its inclusion in two recipes is evidence of a French influence while admitting that “there are perhaps fewer recipes from French cuisine than one might expect.” (Hess, Virginia House-wife xxv-xxvi, xxxi)

Hess thinks five purportedly Spanish recipes and “Italian” ones for “Verecelli” and “Macaroni” confer a notably cosmopolitan cast on The Virginia House-wife but the same or similar recipes also appear in British cookbooks of the period. Both varieties of pasta appear in seventeenth century British sources too and were widely recognized by the public as indicated by a popular song; “Yankee Doodle.”

According to Hess, the variety of produce available to eighteenth century Virginia cooks was unparalleled, but the source she cites, William Byrd’s 1737 Natural History of Virginia, lists crops equally common to an English garden of the time, with the possible exception of squash.

She also ascribes novelty to recipes that instead are typical of the time. She finds, for example, a cooking time of an hour for boiled turkey “rather unusual in method and illustrate… the short cooking times she favored,” but in fact a turkey does take about an hour to boil, and printed sources reflect the fact.

Without describing it, Hess claims Randolph represents “an elemental change in palate” for Virginia compared to the rest of the western Anglosphere. “All evidence,” she announces, “indicates that… Virginians had become accustomed to headier seasonings than were the English, or New Englanders, for that matter.” (Hess, Virginia House-wife xxvi) Hess, however, cites no evidence for the proposition and for good reason. It is utterly anachronistic, although the notion that eighteenth century British food was bland remains a common misperception.

Cayenne to cite a single example had been called “ginnie” or Guiana pepper in sixteenth century England. (Small 157; Gerard)

A British 18th century invention.

“Cayenne pepper, also spelled ‘cayan,’ ‘chyan,’ and ‘kian,’” Marisel Presilla explains, “was well established in English cookbooks by about the middle of the eighteenth century.” Presilla adds that a “persistent habit of using cayenne pepper in fish dishes developed in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries in English as well as English-influenced US cooking.” (Presilla 117)

At first the English imported the chilli but cayenne powder itself was their creation. As Presilla recounts:

“It was made by drying the pods set on layers of flour before bashing them to a powder with the flour, moistening the mixture, making it into small loaves, drying them in the hot sun or an oven, and grinding the loaves to a powder.”

The 1755 editions of The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy include recipes calling for cayenne, ranging from curries and jugged hare to turtle.

By 1817, the English were cultivating chillies themselves. In his bestselling Cook’s Oracle, William Kitchiner recommends making cayenne from English chillies because “Indian cayenne is prepared in a very careless manner, and often looks as if the pods had lain until they were decayed.” (Kitchiner 282)

By then cayenne was ubiquitous in British kitchens. Kitchiner, whose book enjoyed numerous editions in the United States, lists it among eleven larder essentials along with several ketchups and other flavorings. He includes cayenne in “Bonne Bouche, for Goose,” “Duck, or Roast Pork;” “Orange Gravy Sauce;” “Piquante Sauce for Cold Meat, Fish &C;” and “Turtle Sauce.” The Oracle also includes instructions for liquid essence of cayenne, cayenne vinegar and cayenne wine, his curry powder; “Pea Powder” (for spicing the soup) and “Savoury Ragout Powder” contain the chilli too. (Kitchiner viii, 262-63, 281-83, 296-97)

As for early New England, Keith Stavely and Kathleen Fitzgerald demonstrated years ago that the reputation of its cuisine as bland and stodgy is equally unfounded.

5. What about India?

Hess speculates that

“Mrs. Randolph’s Dish of Curry after the East Indian Manner may… be from Indian rather than English sources; she gives a recipe for Curry Powder.” (Hess xxxiii)

The assertion is wrong in every respect. The most cursory glance at the Dish of Curry demonstrates its British (the Scots, too were famous for curry by the end of the eighteenth century) rather than Indian origin. The technique is British, essentially a simmered stew flavored with curry powder: “Cut two chickens as for fricassee,… let them boil till tender,… then put in half a pound of butter…. ” Randolph 93-94)

As for the powder itself, Mr. Randolph refers to it but does not describe its components let alone offer a formula.

Curry powder was unknown anywhere until the British invented it in the eighteenth century. Before then none of the myriad cuisines of India cooked with a premade spice mix. Instead, Indian cooks added spice separately to any given dish at different stages of the cooking process, usually a smaller variety of it than appears in a curry powder.

Finally the term curry itself is so closely associated with Britain that a number of Indian authors decry its use to describe Indian foods. Some have gone so far as to find it racist. Sameen Rushdie (sister of Salman), who wants not in confidence, writes in her Indian Curry that she is “deeply offended by its racist connotations.” (Rushdie 12) The young Madhur Jaffrey also tagged the term racist, although she later recanted in inferential but spectacular fashion with the publication of her Ultimate Curry Bible during 2003.

6. The X factor.

In common with Carson and Colonial Williamsburg, Hess fails to make the case for exceptionalism in the Virginia kitchen and her ascription of unique qualities to The Virginia House-wife is misplaced. That is not to argue that the book is not good--it is--or that Virginia did not exhibit distinctive foodways influenced by its peculiar circumstances.

The wild card in the eighteenth century Virginia kitchen is the slave. Hess understands the fact and gives full credit to her immense if subtle influence on Tidewater cuisine. “New England women,” Hess explains, “were dissidents who for the most part did their own work; any servants tended also to be English.” That contrasted with the Virginia gentry. In their kitchens, as Hess says, “black women slaves traditionally did the cooking.” (Hess, Virginia House-wife xxix)

Hess does not, however, much describe the black influence other than to mention gumbo (a Louisiana creation), pepper pot (more prominent in Philadelphia) and “a-la-daube” (which also appears in British cookbooks). The omission may not be an oversight because while unquestionably important, the influence of Africans and African-Americans is difficult to chart across time, particularly in Virginia. “The black contribution,” Hess admits, “was infinitely more subtle in Virginia cookery than in that of New Orleans or the West Indies,” and, she might have added, the Carolina lowcountry, “but no less real for that…. ” (Hess, Virginia House-wife xxxi)

The difficulty is documentation, or the lack of it. Masters routinely consigned slaves to illiteracy and took no interest in recording their accomplishments, so the written record is sparse.

To her credit, Hess provides a good insight on the murky but decisive influence of the slave in the kitchen. “I think,” she surmises, “because in addition to actual borrowings, there is the thumb print that each cook leaves on a recipe, even within the same culture, no matter how skilled she may be or how faithfully she follows a recipe.” (Hess, Virginia House-wife xxx) That imprint is not, however, apparent from the recipes in The Virginia House-wife.

7. Is there an eighteenth century Virginia cuisine?

The Virginia House-wife enthralls Carson, Hess and Historic Foodways. Hess goes so far as to claim that “nothing in the history of early American cookbooks prepares us for the sumptuous cuisine presented by Mary Randolph.”

Biographers tend to fall in love with their subjects; historians tend to overstate the significance of their topics as Hess became overenamored of hers. So she adds without evidence that Randolph “brought her personal flair to everything she did” and claims for The Virginia House-wife something nonexistent, “an eclecticism, which flowed from the fascinating interplay of strikingly different influences that manifested themselves from the very beginning,” whatever that means.

It gets more ridiculous when Hess claims that a “certain eclecticism has continued to mark American cookery, but never with such éclat.” (Hess, Virginia House-wife xxi) Any number of Louisiana cookbooks alone down the ages puts paid to that unsubstantiated claim.

The reality is not so spectacular. Randolph’s is, as noted, a good book, but represents only a variation on the diverse British publications of its time. It is not, as Hess argues, more modern in tone than Raffald or Glasse (consider all those Elizabethan and Jacobean recipes she identifies) although, as Hess points out, Randolph does include recipes, like okra with tomatoes, that are particularly American.

To the extent The Virginia House-wife does embody the foodways of its region or time--and research remains required to determine whether it did--the cuisine it reflects is no more distinctive than the cuisine of New England, and unquestionably less distinctive than the cuisines that developed early in Louisiana or the lowcountry, and not only because of the more significant black contribution.

Louisiana in particular benefited by the time of Mrs. Randolph from its polyglot culture: African; Caribbean, and especially Haitian; English; French; German; Italian; Native American; Scottish and Spanish techniques all are apparent influences on the foodways of early Louisiana. While Hess identifies, or misidentifies, a number of dishes in The Virginia House-wife that originated outside the United States or England, most Louisiana recipes are recognizably unique even as they draw from disparate sources.

8. Back to the beginning and Colonial Virginia Cookery.

“That the future may learn from the past”

Hess is commenting on two discrete texts, her modern transcription with commentary of the Custis manuscript and a facsimile reprint of The Virginia House-wife. Colonial Virginia Cookery is more elusive than either of them, because instead of explicating a discrete text, Carson has tried to recreate the cuisine of a time and place based on the manuscript and a clutch of publications that were purchased by its inhabitants.

Her own book has a singularly anachronistic element. A euphemistic reference to “illiterate servants” who “could not follow written directions” in fact screams “slaves” but the subject of slavery itself gets scant mention and no index entry. A black contribution to the cuisine of Virginia gets no mention at all, but by inference was negligible if not nonexistent.

According to Carson, during an interview in 1840 “an aged Monticello slave named Issac” provided the answer to the problem of illiteracy in the Virginia kitchen. “Mrs. Jefferson,” he is said to have recalled, “would come out” to the kitchen “with a cookery book and read out loud of it” to the cooks. (Carson xi) No other mention of slavery, slave cooks or their culinary culture appears in Colonial Virginia Cookery and none of its recipes reflects their influence, but then Carson was writing in 1968.

To return now to the subject of Carson’s stated mission of recreating the cuisine of the early Virginia gentry, she juxtaposes recipes from each of her sources to comment on their similarities and differences. What emerges for the most part are Randolph recipes no more distinctive from the English sources than the recipes of the English sources from each other.

Glasse, Raffald and Randolph each describes how to assemble and present salamagundi, a sort of kitchen sink precursor of chef’s salad ubiquitous to Virginia and Britain (but apparently not New England based on Amelia Simmons) in the eighteenth century. None of the recipes or presentations is the same but they all share common elements.

To note but two more among many examples, bread sauces (ineffably English) and white sauces from Randolph and all Carson’s English publications are virtually identical, amounting to minute variations on a common theme. So while she compares sources to an extent that Hess does not attempt, Carson ironically makes the lesser case for a distinctive Virginia cuisine during the colonial and, notwithstanding her chosen title, early national periods.

Sources:

Jane Carson, Colonial American Cookery (Williamsburg 1968)

John Folse, The Encyclopedia of Cajun and Creole Cuisine (Gonzales LA 2004)

John Gerard, The Herball or Generall Historie of Plantes (London 1597)

Hannah Glasse, The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy (Prospect Books facsimile Totnes, Devon 1995 orig. publ. London 1747, 1755 and other, including North American editions)

Karen Hess, Martha Washington’s Booke of Cookery (New York 1981)

“Historical notes and commentaries on The Virginia House-wife,” in Mary Randolph, The Virginia House-wife (orig. publ. Washington DC 1824; facsimile 1984 Columbia SC)

Madhur Jaffrey, Madhur Jaffrey’s Ultimate Curry Bible (London 2003)

William Kitchiner, The Cook’s Oracle (London 1817)

Maricel Presilla, Peppers of the Americas: The Remarkable Capsicums That Forever Changed Flavor

(New York 2017)

Elizabeth Raffald, The Experienced English Housekeeper (London 1769)

Sameen Rushdie, Indian Cookery (London 1988)

Ernest Small, Top 100 Food Plants: The World’s Most Important Culinary Crops (Ottawa 2009)

Keith Stavely & Kathleen Fitzgerald, America’s Founding Food: The Story of New England Cooking

(Chapel Hill 2004)

Northern Hospitality: Cooking by the Book in New England (Amherst 2011)