The real, the surreal & the dirty: Perspectives on Colonial Williamsburg, anachronism, authenticity & pirate zombies.

1. A vision both radical and reactionary.

In 1926, an unprecedented construction project began in a small American city that was down on its luck. It was not the biggest project undertaken at the time, not by any stretch, nor was it in any way innovative in terms either of planning or architecture. The aim of the project was not economic revival and the developer who bankrolled the project disregarded any opportunity to profit from it.

He was John D. Rockefeller, Jr. His architects and contractors were implementing the vision of an obscure religious education professor at a college that was not even the flagship campus of a state university system.

W. A. R. Goodwin belonged to “a new breed of preservation campaigners” who, Ashley Jackson, explains, “began to articulate a growing interest in America’s colonial heritage and the protection of its historical sites.” Goodwin’s target was Williamsburg, Virginia, and he persuaded Rockefeller to travel there and consider a pathbreaking if backward looking proposal.

Goodwin believed his chosen site could become “a unique window onto the national past. His pitch to Rockefeller was that Williamsburg was the one colonial city left that had not been obliterated or swallowed up by urban growth.” (Jackson 61) Williamsburg was not really unique in that respect, but no matter.

2. Make no small plans.

Goodwin proposed restoring a number of extant structures over time. Rockefeller was sold on the concept of restoration, but his own vision eclipsed anything Goodwin had anticipated. “After wandering around the town,” Jackson continues,

“Rockefeller declared that this was an irresistible opportunity, not to restore the town piecemeal, but to reconstruct it in its entirety, giving Goodwin far more than he had bargained for.” (Jackson 62)

Rockefeller wrote at the time that his expanded project

“offered an opportunity to restore a complete area entirely free from alien or inharmonious surroundings as well as to preserve the beauty of the old buildings and gardens of the city and its historic significance.” (Yetter 10)

Every aspect and prospect of the colonial capital would return in appearance to the eighteenth century. Acres would be purchased in and surrounding the town. Structures built after the era would be demolished and their inhabitants relocated. Extant buildings would be restored and new ones constructed in the eighteenth century idiom on an unprecedented scale.

Rockefeller was as good as his words. At the outset the project razed some seven hundred thirty structures built after the cutoff date of about 1770. (Huxtable 2) “The most famous of America’s restored and reconstructed historic villages, the most impressive, and one of the largest,” according to Jean Anderson,

“Colonial Williamsburg stretches almost one full mile along Duke of Gloucester Street from the restored Sir Christopher Wren Building (1609) on the College of William and Mary campus to the reconstructed Capital. There are eighty-eight fully-restored and preserved eighteenth-century buildings here and more than fifty faithful reproductions that have risen from the rubble of structures destroyed during Tidewater Virginia’s march of progress.” (Anderson 117)

Anderson’s tally is not quite right, in part due to some sleight of hand by the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation that operates the place and in part due to sloppy editing. A number of the eighty-eight “eighteenth century” buildings are no such thing but rather mid-twentieth century reproductions. A significant proportion of them incorporate nothing more original than a few fragments of brick foundation or a shard of retaining wall, so that the ‘restorations’ necessarily are speculative.

Most commentators refer to some five hundred, not fifty, reproductions: In 1997 Ada Louise Huxtable counted precisely four hundred thirteen. (Huxtable 2)

3. A case study in aspirational instead of empirical scholarship.

The first building the foundation ‘restored,’ starting in 1928, stands as an instructive case study. The ‘Sir Christopher Wren Building’ at the College of William & Mary burned in 1705, 1859 and 1862. The interiors were lost without documentation and only a fragment of brickwork above the foundation survived. For good reason, it was not called the Wren Building until the 1930s. During its first century the structure was the “College Building” and in the nineteenth century it became the “Main Building.” The third name only

“was selected in the 1930s during the Colonial Williamsburg restoration of the building and was based on a reference from Hugh Jones, an 18th-century professor.”

The choice presents a problem emblematic of the questions about authenticity that plague Colonial Williamsburg. “The university,” Suzanne Seurattan admits, “doesn’t actually have any proof that the Sir Christopher Wren Building was designed by Wren.” The only reference connecting Wren to the building is the Jones journal, which he wrote “around the times of Wren’s death when it was popular to attribute things to Wren” that he did not design. (Seurattan 5)

Jones himself was a small child when the College Building was constructed so his account appears somewhat suspect, untethered as it is to any source. For bad measure, Jones himself qualified his speculation attributing the design to Wren with the admission that “it was adapted to the Nature of the Country by the Gentlemen there.” (WPA)

Even if the adaptation arose from Wren’s office he may not have had anything to do with it. By the time the building at William & Mary was constructed ‘his’ designs and structural plans often were drafted by Nicholas Hawksmoor, whose genius surpassed even Wren, Robert Hooke, John Oliver, Edward Woodroff and other architects in the office. (Jardine 306) And in her exhaustive biography of Wren, Lisa Jardine omits any mention of either the building or its college.

The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation admits that the attribution to Wren is aspirational rather than documentary. The Wren building as it stands is the result of exhaustive research based on several layers of speculative assumptions. Notwithstanding the Jones disclaimer and absence of corroborating evidence, the foundation based its reconstruction on Wren. In 1969, Catherine Savedge of the foundation wrote somewhat awkwardly about its 1928 renovation:

“The designs of specific architectural details were derived largely from English prototypes with the primary sources of precedent being Oxford and Cambridge Universities (where Wren buildings exist), Eton College in Buckinghamshire and the Free School of Harrow in Middlesex (constructed between 1595 and 1611). On the authority of Hugh Jones’ statement in 1724 describing the second building as ‘not altogether unlike Chelsea Hospital’ in London, also designed by Wren and begun in 1682, many features restored to the Great Hall and Chapel in 1928 were copied from comparable rooms there. Otherwise, the designs are typical colonial Virginia derivatives.” (Savedge 2)

Williamsburg chose to reimagine the Great Hall and Chapel based on some of Wren’s grandest interiors in a conscious effort to confer an elegance on the building it likely did not possess based on an unreliable and equivocal source.

None of this will appeal to the rigorous scholar of architectural history, based as it is on the unlikely conjecture either that Wren had anything to do with the building or, if he did, he based any of it on his previous designs.

4. A capital idea….

The Williamsburg Foundation never has pretended that the colonial capital is anything but a replica. Its architects chose to imitate the 1705 building destroyed by fire in 1747 instead of the more modest structure standing in 1770, which would result in an inadvertent irony on the part of Rockefeller himself.

The new building

“turned out to be different from the original in several key respects because the architects simply could not get into the minds of their architectural forebears, to the extent they ignored compelling evidence.”

The Beaux Arts architects ignored archaeological evidence that the original building had been asymmetrical. “Their stubborn rejection of the evidence was based,” Jackson explains, “upon their deeply rooted aesthetic preference for compositional balance and axial symmetry.” As a result they “tended to embellish or improve beyond what the historical evidence warranted.”

As with the Wren Building, the architects and Rockefeller took it as their brief to emphasize the

grandeur of the American moment they sought to replicate, a brief that argued against the “architectural quirks [that] abounded” in eighteenth century British North America. (Jackson 64) Carl Lounsbury, adjunct professor at William & Mary and an architectural researcher with Colonial Williamsburg, explains that its initial creators

“recorded mantels, stirs, cornices, doors and other features from the best gentry houses in Virginia, which they integrated directly into many of their designs for the reconstructed buildings in the historic area.”

In this case heaven was not, pace Mies, in the details, which were accurate. The Colonial Revival architects of Williamsburg, however, “had only an imperfect understanding of how these details fit together.” (Klein)

In the ironic twist, Rockefeller would write that he was tempted to sit in silence at the capital “‘and let the past speak to us of those great patriots,’ to whose memory he dedicated the reconstruction.” None of them, however, would in fact have entered the building. As Jackson notes, it was not even a recreation of the structure that witnessed “the momentous events of the 1770s.” (Jackson 65)

5. Ahead of their time, if inadequately.

Despite its infelicities in terms of accuracy, the task of recreating Williamsburg had been undertaken with a species of archival rigor, as the story of the Wren building illustrates. “This process,” Eric Gable and Richard Handler recount, “was overseen by architectural historians whose main concern was ‘visual authenticity.’” To their credit they broke a certain mold:

“At a time when most historians had no interest in so-called material culture, these architects were documenting buildings and treating buildings as documents. They travelled throughout the Virginia tidewater region to locate surviving period buildings and compose sketchbooks of architectural and decorative details.” (“Deep Dirt” 5)

In the estimation of Lounsbury, while

“the final result is a testament to the architects’ skills in handling 18th-century detailing, the capital now stands as a monument to the near past and tells us much about the influence of Beaux-Arts design principles on the restoration of Williamsburg as about the architecture of the colonial period.” (Lounsbury 373)

In a way Lounsbury is observing that the founding methodology of its creators made Williamsburg something less than the sum of its parts in eighteenth century terms. He is not, however, unsympathetic to either the institution or the built environment it has inherited.

In his less charitable assessment, Richard Guy Wilson calls Colonial Williamsburg “a superb example of a suburb of the 1930s, with its inauthentically tree-lined streets of Colonial Revival,” and, he might have added, therefore Beaux Arts “houses and segregated commerce.” (Wilson)

Check out the pristine copper pans.

6. Attack...

A cadre of scholars has been even unkinder to Colonial Williamsburg since at least the 1960s. The fiercer critics claim that an outright fantasy beyond even invented authenticity mars its reincarnation. Goodwin himself worried about the commercialization of his project and prefigured their concerns when he retired. “If,” he insisted,

“there is one firm guiding and restraining word which should be passed on to those who will be responsible for the restoration in the future, that one word is integrity.”

Goodwin warned the foundation that “departure from truth here and there will inevitably produce a cumulative deterioration of authenticity and consequent loss of public confidence.” (Montgomery)

He was too late. The departure he decried had been taken from conception, in a certain respect Colonial Williamsburg’s original sin. The well-intentioned aim all along had been the seamless integration of old and new, real and artificial, true and false, in pursuit of a higher civic truth. Williamsburg would embody and embellish the ideals of the founders with what one populist apologist calls “an impeccable colonial village.” (Mariani)

Critics of the hortatory project consider its aim dishonest and dangerous. The theme park that is Williamsburg was conceived as an immersive experience that prefigures the current craze for the digital presentation of virtual reality. Tourists could inhabit a sanitized eighteenth century world scrubbed of its insalubrious and inconvenient elements.

Gable and Handler are two of the more extreme but also thoughtful commentators to address what might be considered the physical historiography of Williamsburg. They are not unsympathetic to the plight of its staff, noting that a number of scholars and pundits are predisposed to think unkindly of the place “for producing a bowdlerized past.” They themselves attack them and it, however, for promoting “an airbrushed past.”

In the estimation of Gable and Handler, the staff at Colonial Williamsburg would

“…. Justify good myths over bad facts, or authenticity as a model for, rather than a model of, a reality…. When they lay claim to being the enlightened arbiters of universal values--servants and guides to the people--they impart to us what are self-serving visions of how the past should look.” (“After Authenticity” 572, 575, 576)

They decry what they consider the elitist cant of the enterprise in more detail while couching their criticism in terms of unnamed “other critics.” In their view,

“Colonial Williamsburg is simply ‘too clean’ to be a faithful recreation of the past. Cleanliness, here, has its literal meaning: Colonial Williamsburg’s grounds and buildings are too well kept to be accurate to the eighteenth century.”

Not enough of these around for authenticity.

The problem, however, runs deeper than hygiene, which Gable and Handler concede Williamsburg has instituted a praiseworthy policy of negligence. “To avoid kitsch and inauthenticity,” they explain, “Colonial Williamsburg planners have,” since the early 1970s, “sought to introduce dirt, ruin and decay into the restoration,” including “animal droppings… purposefully left on the streets.” (“Deep Dirt” 3-4, 7)

The also have made a number of interiors more modest and attempted over the years to introduce more accurate reconstructions based on the archeological record.

From the perspective of the anonymous critics, however,

“Colonial Williamsburg is too clean in another sense: it presents a bowdlerized version of the past, long on inspiration and high on the social ladder. Historical ‘dirt’--the chaotic and dismal facts about poverty, squalor and class oppression--has been swept out of sight, to the detriment of realism and hence of the museum’s educational mission.” (“Deep Dirt” 4)

6… and defense.

Williamsburg is not without defenders. Anderson for one was riding a popular wave of interest in things colonial in 1975, on the eve of the American bicentennial. She sustains no sympathy for the critics. “Architectural purists and historians,” she complains,

“have sneered at Colonial Williamsburg, claiming that it sprang full-blown from the drawing boards in the 1930s…. But they generalize too much. Williamsburg rests upon solid historic foundations.” (Anderson 118)

In reality, as the pedigrees of both the Wren and capital buildings demonstrate, it is Anderson who generalizes too much. And yet John Mariani sounded a similar note just this year. Mariani, a culinary historian and cookbook author, has written fifteen books, although one of them is Grilling for Dummies. According to him,

“some sticklers sniff that the creators of Williamsburg somehow Disney-fied American history by recreating an impeccable colonial village complete with hotels, restaurants, carriage rides and cooking demos [sic]. It is a charge with no merit.”

“For one thing,” Mariani continues, “‘CW’ pre-dates Disneyland by three decades…. In fact, Walt Disney World’s The American Adventure attraction in Florida owes its inspiration to CW.” (Mariani)

It is an uninformed assumption and empty argument that contradicts itself. In 1965, Huxtable had in fact maintained:

“The replacement of reality with selective fantasy…. probably started in a serious way in the late 1920s at Colonial Williamsburg, predating and paving the way for the new world order of Walt Disney Enterprises. Certainly it was in the restoration of Colonial Williamsburg that the studious fudging of facts received its scholarly imprimatur…. ” (Huxtable 1)

The Disney empire and its American Adventure only exist, Huxtable argues, because of the pernicious precedent of Colonial Williamsburg.

It is easy enough to dismiss Mariani as a slob, but Huxtable also poses a pedagogical problem. True to her strident modernist proclivities, she betrays a bellicose bias in her assessment of Williamsburg. Only a lot less clapboard and brick at the site, and lot more I-beams and glass, could have satisfied her.

A design Huxtable might have preferred.

These days Williamsburg struggles to appeal to its audience of tourists while attempting to fulfill its mission of promulgating popular history and simultaneously placating its academic critics. To the credit of Gable and Handler, they temper their criticism with some balance and not just through their endorsement of dirt. Around 1978, they note with satisfaction,

“Colonial Williamsburg’s curators have been involved in a sustained scholarly effort to improve realism by decreasing the elegance of the museum’s interiors.”

They, Lounsbury among them,

“have argued that the first generation of curators and architects were influenced by ‘Colonial Revival’ high style and that faithfulness to the eighteenth century requires a ‘leaner look.’” (“Deep Dirt” 15n5)

In an article from the Colonial Williamsburg Bulletin plaintively entitled “They Did the Best They Could,” Gil Klein quotes Lounsbury to explain why some of the choices the first generation made would prove problematic to their successors.

Comparing his own contemporaries to the first generation, Lounsbury emphasizes the distance between their intellectual approaches:

“Many of us are social historians interested in the dynamics of colonial society. While we seek precedents on which to base our designs, we do not slavishly copy detail from the best houses. We seek to understand the hierarchy of ornamentation that would be appropriate for each site, building and room.”

Lounsbury himself displays no small degree of affection for the first generation at the site. According to Klein, “he is in awe” of their achievement considering, also in Klein’s words, “the tools and knowledge they had” and the severe time constraints that required reconstructing hundreds of buildings in only three years. (Klein)

7. The fight for a past, or for competing pasts.

Perception of the past, or perhaps of the appropriate way to reimagine it, has changed with the times. If populists and academics alike shared a penchant for idealizing American history during much of the twentieth century, a substantial school of thought that emerged toward the end of it would demonize much of that history instead, and break it into fragments that undermine any notion of a unified polity. Instead of striving to match the ideals of the founders, the revisionists insist that the United States need to clean up their mess.

In between those poles stand the sticklers for accuracy and authenticity who unfortunately display a species of confusion. Authenticity poses a particular dilemma. If, as historians from E. J. Hobsbawm and Hugh Trevor-Roper to Carrie Helms Tippen insist, authenticity is invented, it has become an elusive notion. That remains the case even where, as at Williamsburg, the historical project is founded on a built environment. That environment is, as the documentation and lack of it demonstrate, somewhat fictive, and purposely so in pursuit not only of the civics lesson Rockefeller wanted to impart, but also as a means of implementing the dangerous if sometimes well-intentioned concept of a higher truth.

It is easier, especially for revisionists, to decry something as inauthentic than to determine the authentic, which puts the stewards of Williamsburg in an untenable position. If the place is more palimpsest than photocopy, they have inherited a valuable artifact conceived in a legitimate enough intellectual environment now considered anachronistic. But Williamsburg is, at least, an embodiment of the culture that created the Colonial Revival and, at best, an artificial evocation of the American past that may inspire people to embark on its serious study.

Maybe the United States could benefit from a return to the kind of unfashionable civics that Rockefeller revered. It is not only that the subject has not been taught in high schools for decades: History itself has fallen from favor.

According to Khalil Gibran Muhammad, who holds a chair at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, American students “are virtually illiterate on the subject” even of slavery, “and this has had severe consequences for our national life.” (Muhammad) Although it cannot fill the void, at least the topic has been central to the daily reenactments at Williamsburg for some time now. The place has its place, even if only to offer families with children an alternative to the dreaded fantasy theme park.

The absence of civics from the national curriculum itself has had severe consequences. Millennials and younger cohorts seldom vote, a number of scholars believe because they do not know how the better angels among us have managed to drag the United States past Jim Crow, antifeminism or homophobia, all unfortunately threatening to return under the malignant auspices of Trump. People with no civic vision cannot comprehend the stakes of an election.

Applying the same constructivist methodology as Gable and Handler, Edward Bruner reaches a different conclusion about the efficacy of replicatory sites like Williamsburg. He is the better writer, and for him the conflict is not between elegance and squalor, hokum and rigor, or propaganda and inclusivity.

“The contest,” Bruner believes,

“is between the museum professionals and scholars who seek historical accuracy and authenticity on the one hand, and the people’s own popular interpretation… as it is manifested in a given site in contemporary America on the other.”

No visitor arrives at Williamsburg or anywhere else without expectations, and Bruner welcomes them all. He is the rare scholar who would not confer special status on scholarship, let alone his own anthropological model. “Historians,” he maintains, “don’t own history, and they have some powerful competition in interpreting the past.”

In his view that is no bad thing: “Fortunately, no one group can impose an interpretation” on any given subject,

“and it is precisely in the struggle over meaning in historic sites, museums, and tourist attractions that the diverse segments of a democratic society are able to express their interests and stake their claims.” (Bruner 128-29, 144)

Gable and Handler are decent enough to describe Bruner’s competing vision in civil terms:

“He asserts that the production of authenticity-as-verisimilitude is no more or less than a clear manifestation of what culture everywhere and always is--an invention (in many instances based on an attempt at replication). As such it is a benign fact. It is benign, too, because it allows natives [that is, the operators of historic sites in the awkward terminology of Gable and Handler] to play with an invented past and revivify certain enduring ideals relevant to their present and future.” (“Deep Dirt” 575)

Taken within reason as with all things, Bruner’s more generous vision is the better one.

8. Foodways then and again.

Anderson and Tippen are, like Mariani, culinary historians. Anderson is more populist than Tippen, as her reference to a somewhat dubious ‘tidewater march of progress’ infers, and also a writer of recipes. Her references to Williamsburg arise, it transpires, from a cookbook called Recipes from America’s Restored Villages. Its inclusion and discussion of recipes from Williamsburg is no outlier: More recipes have sprouted from the project than buildings.

It is a bit of a surprise, then, that Anderson describes only four putative Williamsburg recipes, and that none of them is linked exclusively to the town. “Meat in the early days of Williamsburg,” she maintains, “usually meant ham,” and she is right. Salt beef also was a staple but no meat approached pork in terms of consumption. “Pork was seldom eaten fresh,” as Jane Carson explains, and “[t]he practice of preserving it with salt was so universal that guests in private homes and public taverns found salted meat on the menu at nearly every meal.” (Carson 114, 113)

Problematic spoon bread.

Problematic spoon bread.

Anderson, however, includes corn syrup in her recipe. It did not originate until the middle of the nineteenth century and was not much used until the 1870s. (Smith 170) She also misses the Williamsburg cutoff with a recipe for coleslaw, which does not appear in print until 1794 when it referred to “a piece of sliced cabbage” rather than her elaborate version. (Davidson 203)

Her selection of spoon bread also is problematic. While Bill Neal, a trustworthy source, believes it “existed long before it was in print,” the first written reference does not appear in print until 1847 and then in South Carolina rather than Virginia, followed by a Boston recipe called “Indian puffs” in 1850, so in historical terms it is not even exclusively southern. (Fussell 1990) Although not in fact a publication of the foundation, this kind of slovenly scholarship gives credence to critics of Williamsburg.

9. A distillation of time, place and ethos.

From the outset its own vision included a species anyway of eighteenth century food. Four taverns have been recreated to sustain the tourists over the years, the first in 1941, and the luxurious Williamsburg Inn built in Colonial Revival style always has offered ‘authentic’ eighteenth century dishes on its menus.

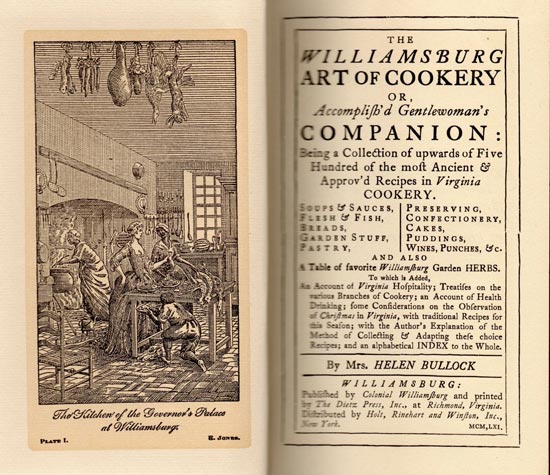

Cookbooks also have been part of the project from inception and the first one represents a fascinating artifact.

The Williamsburg Art of Cookery first appeared in 1938 soon after the initial reconstruction. Its full title and use of typeface illustrate why the artifact is fascinating:

“The Williamsburg ART OF COOKERY OR Accomplif’d Gentlewoman’s COMPANION: Being a Collection of upwards of Five Hundred of the moft Ancient & Approv’d Recipes in Virginia COOKERY. Soups & Sauces, Flesh & Fish, Breads, Garden Stuff, Pastry, Preserving, Confectionary, Cakes, Puddings, Wines, Punches &c. AND ALSO A Table of favorite Williamsburg Garden HERBS. To which is Added, An Account of Virginia Hofpitality; Treatifes on the various Branches of Cookery; an account of Health Drinking: fome Confiderations on the Obfervation of Christmas in Virginia, with Traditional Recipes for this Seafon; with the Author’s Explanation of the Method of Collecting & Adapting thefe choice Recipes; and an alphabetical INDEX to the Whole By Mrs. HELEN BULLOCK”

This is more than a little ridiculous, and becomes annoying as it continues into the 1938 preface and commentary accompanying the recipes, “fome” old and “fome” “adapted.” These “prefent-day Recipes” were created in test kitchens during 1937 by fifteen of Mrs. Bullock’s colleagues. The book is printed on the rough, faux-foxed beige paper intended to create the patina of antiquity and bound in what looks like eighteenth century wallpaper.

It takes no leap to notice that The Art of Cookery encapsulates the original ethos of Williamsburg. The springboard for the book is, as its preface indicates, something published in Williamsburg during 1742. Mrs. Bullock describes it as “THE firft American Book on the Art of Cookery” but that is not quite right. Instead, the book is a condensed, pirated edition of one by Eliza Smith first published in London during 1727. It was the first cookbook published in North America but the first American cookbook would not appear until Amelia Simmons of Connecticut compiled it in 1796.

Smith is not a bad choice. It was the best-selling cookbook in British North American at the midpoint of the eighteenth century, predominantly, however, in London editions, before The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy by Hannah Glasse supplanted it “during the last three decades of the colonial period.” (Hayes 83, 84)

Bullock’s title incorporates elements of Smith (“accomplish’d Gentlewoman’s Companion: being a Collection of upwards of six hundred of the most approved Receipts”) but in a flight of anachronism substitutes the modern ‘recipes’ for the eighteenth century spelling and adds ‘ancient,’ not the selling point circa 1750 that it would become in 1938. Glasse gets a nod as well (“The Art of Cookery…”) and so does the fictitious ‘John Farley’ (“The London Art of Cookery… ”).

The lists including categories of dishes, considerations, observations, explanations, but not the reference to Christmas, which like the usage of ‘ancient’ is a function of interwar marketing considerations, are typical of eighteenth century British cookbook subtitles.

Had Mrs. Bullock confined the recipes in The Williamsburg Art of Cookery to those from Smith along with modern adaptations, she might have created something both accurate and useful in terms of a window on publishing in the Virginia of 1742, but like the original architects of the reconstruction she could not bear not to portray colonial Virginia as more than it was.

Her bibliography (“An Account of the BOOKS confulted in this WORK:”) as well as the sources listed in the text at the end of each recipe demonstrate that she drew on twenty-two texts in addition to her fifteen colleagues. To compound the incongruity, twelve of the written sources date only to the nineteenth century and another to the twentieth; a third is undated.

Citations to two of the eighteenth century publications originally published before the 1770 ‘restoration’ cutoff are to editions published after that date. The subsequent editions continually added content, which makes assessing the authenticity of recipes from those sources unnecessarily difficult. Whatever merits The Williamsburg Art of Cookery may enjoy as a compilation of old recipes, a reflection of foodways as they existed in the Williamsburg that the foundation purported to reflect is not among them.

The chapter called “Of Chriftmas in Virginia” includes a description of the first Christmas tree displayed in Williamsburg. It appeared in 1842 at the request of a “political Exile from Germany.” (Bullock 238) Most of the recipes in the chapter date from the twentieth century.

The riotous anachronism that Mrs. Bullock conjured may be cast, understandably enough, as nothing other than a bit of fun. However, this seamless integration of old and new for purposes high (to create the impression of maximum elegance and sophistication in Virginia during the colonial period) and low (to sell the maximum number of books) has succeeded all too well. A number of catalogs, commentators and other sources list the publication date for The Williamsburg Art of Cookery as 1742. It unaccountably remains in print.

10. Even more anachronism.

In 1982, seismic seizures may have emanated from the grave of the wary Goodwin. By then the publishing arm of the foundation had decided to embrace revenue at the expense of authenticity with Favorite Meals from Williamsburg: A Menu Cookbook.

Not, however, without trying to maintain a pretense of historicism; its introduction purports to describe the food of eighteenth century Virginia in a section called “Menus in Colonial Days” while the section called “Meals at Williamsburg Today” refers to dinners during 1766, 1772 and 1785 to infer that dining at Williamsburg during 1982 would evoke the eighteenth century. The section does refer to modern facilities; it does not refer to modern food.

Favorite Meals from Williamsburg, reprinted at least once, in 1987, is but a moneyspinner aimed at tourists entranced by anything they might eat at one of the foundation’s several dining outlets.

One dish, “Captain Rasmussen’s Clam Chowder,” would be unrecognizable to anyone alive in the eighteenth century, laden as it is with those clams along with garlic, green peppers, tomatoes and tomato puree. (Perkins) The recipe for “Yorkshire Meat Pies” starts with a package of frozen mixed vegetables and also resorts to tomato puree. Seafood Newburg is a creature of the gilded age: Turkey Tetrazzini requires no comment.

11. Cracks in the façade of falsehood.

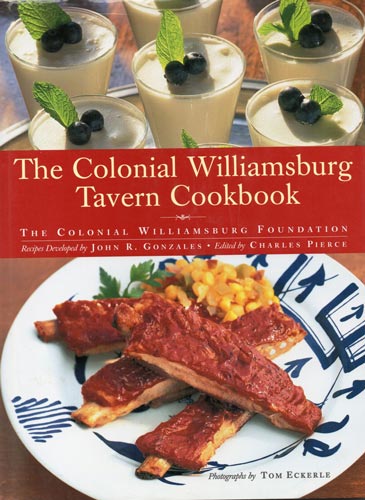

The twenty-first century work of John Gonzales is better. He served for a time as executive chef in charge of the four operating taverns and other restaurants owned by the foundation at Williamsburg. Later, he wrote The Colonial Williamsburg Tavern Cookbook in 2001 followed by Holiday Fare: Favorite Williamsburg Recipes in 2004, both published by the Williamsburg Foundation.

Neither of them purports to recreate eighteenth century dishes; both of them are lovely books. The Tavern Cookbook is candid in declaring that “the dishes owe their inspiration to the distant past, but their preparations have been tailored to modern palates.” Many, not all, of the recipes are evocative of the past, but in many cases not a past that includes the era of the Williamsburg reconstruction. None of them may stake a claim to authenticity and Gonzales refrains from the attempt. That is an admirable departure from much of Williamsburg’s prior practice either in print or at its taverns.

The barbecue sauce based on ketchup, chowders as presented, glazed pork and other dishes would not appear until after the eighteenth century; Worcestershire as well as steak and kidney pie are nineteenth century inventions, the sauce a creation of Mr. Lea and Mr. Perrins in 1835, the pie of Eliza Acton a precise decade later.

The decision by the foundation even to publish either cookbook is problematic in terms of its avowed educational purpose. The work of Gonzales himself however is unambiguously legitimate because he offers good recipes without fabricating false ancestries for them. His recipes, unburdened by overlong biographies, are varied and accessible.

The Tavern Cookbook has more, and more good, recipes than the holiday compilation. There are some absurd additions to the eighteenth century Anglo-American canon including polenta with zucchini, tomato sauce with typically Italian herbs. Vermicelli pie, however, has an ancient English antecedent called Roman pie, essentially the same thing and, as Gonzales apparently understands, worth retrieving from the seventeenth century.

The good British cast of many recipes in the Tavern Cookbook is plain. For starters: Cheese wafers with the unlikely but welcome snap of ginger represent a welcome variation on English cheese straws; “Meat Patties in Crust” amount to simple pasties filled with ground ham and beef; the crawfish soup deserves more Sherry but otherwise shines; watercress soup is an epitome of British technique. Skip the crab salad to opt for crabmeat maison from Galatoire’s instead. Notwithstanding their appeal, all the serving sizes for these recipes are anachronistic. “The bite-size tidbits that accompany pre-dinner drinks and the light foods that make up the first courses of dinners today, Gonzales discloses, “were not served in colonial Virginia.” His starters, “inspired by old recipes from eighteenth century Virginia,” represent one of the many compromises concerning the historical record at Williamsburg.

A pair of noteworthy salads, however, would have appeared along with a central “standing dish”--in Virginia, usually the ham--on the table along with an array of other dishes at the same sitting. Diners would help themselves to whatever they wanted. The first salad; a combination of lettuces, orange and walnuts; the second, a stripped salamagundi derived from the more ornate but flexible prototype prescribed by Mrs. Glasse, both of them also indisputably British in derivation.

For mains: Perhaps best of book, Gonzales has crafted a game pie with brown sauce that Mrs. Grigson could commend except for the stock cube. It includes a couple of welcome shortcuts in the equivalent of Kitchen Bouquet (“bottled brown gravy sauce,” or commercial mirepoix) and frozen pearl onions, both Things We long have Liked in these pages.

Otherwise bubble and squeak, East India fried chicken (a dose of cinnamon properly accounts for the reference to the subcontinent), egg and onion pie, oyster loaves from the streets of eighteenth century London, pot roast in ginger beer, a good welsh rabbit (but misstyled rarebit), an inspired dish of salmon collops (brave of Gonzales to use the British term) with cabbage and fennel, and a trifle (from Rules: Gonzales knows London too).

Gonzales has made good selections from the early North American canon as well, from buttermilk pie, collards, simple creamy grits (“not quick cooking,” Gonzales draws a line), jonnycakes (but misspelt by the addition of ‘h’ the way autocorrect would insist) and succotash (convenient canned beans!) to Brunswick stew and a fish muddle which, however, should not include tomato. Apologies for the long listings but a Williamsburg battered by its at times erratic approach to the past deserves some credit where due.

12. Redemption of sorts in the kitchen and online.

Although the first reconstructed tavern started serving food in 1941, the foundation did not found its Department of Historic Foodways until 1983. (Gonzales 12; “Historic Foodways”) The department performs research, operates demonstration kitchens at replicated sites in Williamsburg and posts recipes.

The tagline of its website will appall the more academically uncompromising but delight cooks who want to take a stab at an approximation of early American food. It is

“History is Served: 18th-century recipes for the 21st-century kitchen”

A number of critics decry the futility of attempting to recreate dishes from the past, Steven Poole the most strident among them. Cooking equipment has changed, although a steady market ensures that replica gear from virtually any era remains readily available. Ingredients pose the bigger problem: Many have changed nearly past recognition from their ancestral forms, but heirloom cultivation, heritage husbandry and landrace forage erode that barrier as well.

What of the home cook who wants to cook from eighteenth century books? She wants to shop where she shops and use her regular equipment. She also is intrigued by the eighteenth century and wants to dabble. The people at Historic Foodways believe that is fine. And things are not so bad as their slogan infers. Each recipe in fact is two, a reproduction of the original text and a test kitchen adaptation which may veer from verisimilitude. As a practical matter the updates are pretty good.

13. The past is a foreign kitchen.

Ivan Day recognizes the difficulty but sets about cooking from the old sources anyway. So do Alyssa Connell and Marissa Nicosia, who post recipes taken from the Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts at Penn. They call their “public food-history project” “Cooking in the Archives: Updating Early Modern Recipes in a Modern Kitchen.” Particular interest is in the manuscripts and in making the foods they chronicle accessible to a lay audience of cooks.

“We believe,” they declare without elaboration or rationalization, “that these historical recipes belong in the modern kitchen.” To that end, they explain in their turgid academic prose, each post includes more information than Historic Foodways offers:

“ ….clear citations to the digitized manuscript and cataloguing information, a facsimile of the recipe in the manuscript, a diplomatic transcription completed to academic standards, definitional comments relating to ingredients, an updated recipe in modern format, and notes and images from our cooking attempt.”

Connell and Nicosia are candid about the project. They are not seekers after the elusive grail of authenticity.

“In updating these recipes, we are not recreating the experience of early modern cooking; we deliberately use the tools and ingredients readily at hand to twenty-first-century cooks. However, we did begin with a desire to taste the past.”

They wonder, however, what they are tasting: “The past, or something new?” It is a good question that should not require an answer. Although they do believe their results “can mimic their early modern successors,” the process is the point.

As they note, the manuscripts themselves demonstrate that their recipes, mostly copied from other sources, are mutable. Their “own methods of updating are part of this long tradition of circulating and translating recipes among individuals and media--copying printed works into manuscripts, mailing a recipe card, posting on a blog.” (Connell and Nicosia)

Theirs’ and Historic Foodways’ is the better approach. And if the basic methodology is good enough for the Ivy League it should be good enough for Williamsburg and the followers of Historic Foodways, provided the site keeps faith with them by posting sound recipes and resisting the Williamsburg hunger for exaggerated effects. Let the cooks have their fun.

Critics from the ‘give them gruel’ school of realism also will decry the candid confession of “History is Served” that “[t]he recipes here are the foods of the wealthy.” The critique based on wealth begs the question just what other kind of eighteenth century food possibly could appeal to twenty-first century palates. Much of historically appealing food was the food of the rich and it takes no imagination to put porridge on a table. Cookbooks have always shared an aspirational component, and if the great middle of society now can eat what once was confined only to the wealthy, so much the better. And if an impressionistic glimpse of former foodways can inspire the more serious study of the past, better still.

14. Back south to Virginia.

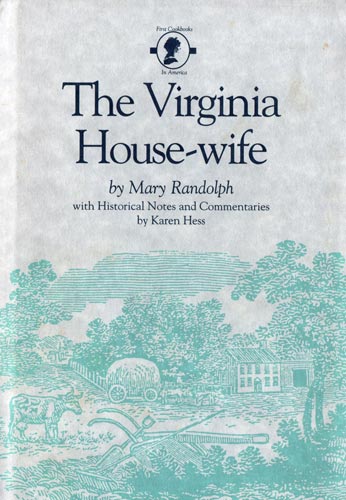

The purpose of the site is legitimate, but the prose can be awkward and its propositions dubious. A cloying populist style careens between the halfhearted conceit that it is an eighteenth century text and explicit contemporary commentary, often in the same short essay. “Why Mary Randolph?” for example, brackets an eighteenth century trope--“truth be told we are an English society, thus we naturally gravitate towards the English cuisine”--with reference to the nineteenth century and to Karen Hess writing in 1984.

Hannah Glasse was not primarily “written to provide housewives and servants to economically reproduce the dishes of the French style that were becoming popular.” Instead, Glasse was a culinary nationalist. Although The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy does include a smatter of unstated French influence, Glasse contrasts French cuisine, its overcomplicated extravagance, richness and expense with sensible, wholesome English food.

15. A digression of sorts concerning tomatoes.

Or consider the tomato. “The earliest tomato recipes in print,” according to Historic Foodways, “date to the third quarter of the eighteenth century.” That assertion is at best misleading and at worst counterfactual. During the eighteenth century most of the English speaking world considered tomatoes poisonous.

Pretty poison.

According to Andrew F. Smith, “only one recipe with tomatoes as an ingredient [sic] was published in the English language prior to 1804.” (Smith 28, 72) It was a ‘Spanish’ outlier that appeared in a supplement to a 1758 version of Glasse and vanished from later editions. (Cutler 8)

Nor is there much of anything in North America dating to the eighteenth century. “Only one colonial cookery manuscript, also according to Smith, “is known to have contained a tomato recipe.” Its author lived in South Carolina and married a Huguenot. Smith speculates that because he had immigrated from France he, unlike the English, may have considered tomatoes edible. (Smith 27)

A single uncorroborated anecdote refers to an eccentric immigrant eating tomatoes at Williamsburg in 1745 but Smith finds it “unlikely that tomatoes were grown extensively in mid-eighteenth century Virginia.” Another outlier was Robert Rutherford. Jefferson had sent him seeds from Paris. He “grew and devoured tomatoes” in western Virginia. “By 1800 Rutherford had convinced only one other person to eat them.” (Smith 28)

Others considered the tomato ornamental but even then vines remained thin on the ground until well after the eighteenth century. As Karen Davis Cutler at the Brooklyn Botanic Garden explains:

“While a few adventurous gardeners grew tomatoes--Thomas Jefferson, who first mentions planting them in 1809, the most prominent--they were not widely cultivated until after 1830.” (Smith 28; Cutler 8)

The Historic Foodways website takes direct aim at a popular audience but even so its historiographical quality should be better given the avowed educational aspiration of Williamsburg.

16. Sources at the inception…

The website includes a bibliography of fifteen cookbooks that its staff of five has chosen for the bases of its recipes, although elsewhere the site says the staff has access to over 140 unnamed sources. The shorter bibliography is a mixed bag. Along with Smith and Glasse, works by Sarah Harrison, the redoubtable Elizabeth Raffald and Martha Bradley, all of them English, were the most widely owned cookbooks in eighteenth century Virginia. (Hayes 83, 84; Carson xii) The bibliography includes Smith, Glasse and Raffald but neither Harrison nor Bradley, curious omissions.

Some of the website sources are good, and the anonymous “Unidentified Cookbook (manuscript), c. 1700, Virginia Historical Society” sounds excellent for the obvious reason that it comes from a working kitchen and therefore provides a record, however incomplete, of things the household actually cooked.

A number of the other sources are entirely appropriate. Richard Briggs cooked in a tavern and William Verral ran a famed one at Lewes in Sussex; Elizabeth Moxon’s recipes would have been reasonably accessible to gentry kitchens. The inclusion of several French Court cookbooks and of books written by cooks from aristocratic kitchens, however, smells like a symptom of the Williamsburg emphasis on an elegance and grandeur that was in fact absent from the North American kitchen.

17 …but also a little late.

And then there is Mary Randolph, whose Virginia House-wife did not make its first appearance until 1824. According to Jane Carson, Mrs. Randolph had been “reputed to be the best cook in Richmond three decades earlier” but that only takes the trail back to 1794.

To be fair, nobody writing about foodways in colonial Virginia, including Carson, has found it possible to resist the allure of Mrs. Randolph despite her tinge of temporal anachronism. Some extenuating circumstances support reference to her House-wife. Published work may trail in time behind domestic or tavern practice, in the estimation of Elizabeth David by a couple of decades, although she typically cites no source. Conversely, however, books can drive trends.

The staff at Historic Foodways has anticipated or perhaps responded (it is not clear) to concern about the late date of The Virginia House-wife. In “Why Mary Randolph?” a staffer maintains that Mrs. Randolph was 62 when she wrote it; based the book “on a solid foundation of cookery learned as a younger woman;” and plagiarized some eighteenth century sources. None of this provides much satisfaction. The staffer further rationalizes using Mrs. Randolph as a source with the argument that “[t]he Virginia House-wife offers something unique--It is also Virginian.” (Costa) So is the food at The Roosevelt in Richmond: It opened in 2011.

A number of recipes in the Randolph book do bear an undeniably traditional English stamp, but then hers also is the first printed recipe for tomato ketchup and the fruit appears in seventeen of her preparations. She is the source of the tomato recipe posted by Historic Foodways. In terms of the tomato Randolph is an early enthusiast and the driver of a trend as much as a recorder of prior practice. Not only was she promoting recipes for the tomato during the decade before its widespread cultivation, she would also “set the standards for tomato cookery for the next three decades.” (Smith 74)

So, while The Virginia House-wife is not necessarily off limits, it is a considerably less reliable indicator of eighteenth century foodways than the contemporaneous sources themselves. Any reference to it requires caution.

18. Back to the eighteenth century kitchen, more or less.

At this writing Historic Foodways has posted a little over a hundred recipes. There are instructional videos and invitations for feedback, which a number of readers have accepted; the staff responds with thoughtful patience. In terms of the recipes, have they chosen the authentic path to the extent anybody could walk it?

Notwithstanding the tomato business it appears for the most part they have. Most of the selections do arise out of the eighteenth century, but a number of the modern versions fail to catch the cast of the original.

In August of 2014, for instance, Historic Foodways posted a recipe for what amount to mushroom pasties from The Complete Practice of Modern Cookery (Edinburgh 1782) by George Dalrymple. The original recipe includes lemon juice, parsley and egg yolks; neither they nor anything similar appear in the twenty-first century version. Garlic does appear in the update, an inexplicable addition because it does not appear in the original. Dalrymple also gives his reader the option of using cullis in the filling instead of “thickening it as a fricassee.” No thickening agent of any kind appears in the newer recipe. In other words the ‘update’ bears no resemblance to the original.

The update also should have included some of the “definitional comments relating to ingredients” like “Cooking in the Archives” but does not even mention the cullis, an extremely rich reduction of stock thickened with sieved meat.

The editing of the recipe is sloppy. The title of Dalrymple’s book is rendered in lower case and his name spelled “Dalirumple,” while one sentence instructs the reader to “dip you [sic] finger in a little flour and run it on top of the most,” meaning moist, “edge” of puff pastry, which makes no appearance in the list of ingredients.

A recipe for “Eggs President Style” is attributed to Dalrymple, a Scot, but he did not call it that and the presidency did not exist prior to 1789. In describing the misnamed dish, Historic Foodways claims without explanation that “[t]he French excelled at egg recipes.”

“Barbecue Shoat or Pork represents one of the recipes from The Virginia House-wife that does have an eighteenth century antecedent. The original recipe explains that shoat “is the name given in the southern states to a fat young hog,” but Historic Foodways does not comment on the usage.

Mrs. Randolph’s recipe is for something resembling a sort of baked pot roast that is stuffed “with rich forcemeat” to “be carved well.” Mushroom ketchup is one of the seasonings and the gravy should be thickened with “brown flour.” Mrs. Randolph gives her reader the option to “add a little sugar,” but only if the gravy “be not sufficiently brown,” so her reference is to browning, the burnt sugar that appears in so many Caribbean recipes, an interesting influence that Historic Foodways fails to mention.

The update is unfaithful to the nineteenth century recipe. The update does not even begin with the same cut of meat. Historic Foodways chose to post a recipe for what amounts to pulled pork shoulder rather than a carved rib roast, although the recipe does give the cook an option to carve the meat at table rather than shredding it.

The forcemeat integral to the eighteenth century preparation is only an option in the update; “fried forcemeat balls” also are optional “as a garnish.” It uses a good dose of brown sugar to sweeten the sauce in the manner of twentieth century barbecue and substitutes Worcestershire for the mushroom ketchup, which is odd as well as inaccurate: Colonial Williamsburg sells mushroom ketchup at its website.

In these two instances the choice of model is fine but the update is very nearly not related at all.

Elsewhere things are not so bad. The recipe from Charlotte Mason for oysters with mushrooms on skewers is inspired and its update hits the mark. The short video is not bad either apart from an overlong and irrelevant introduction featuring irritating recorder music played over images of fresh strawberries and a savory pie.

Like so much else at Williamsburg, Historic Foodways fails to live up to its promising potential.

19. The uneasy case for Colonial Williamsburg.

In the context of the ongoing controversy about whether the very existence of Williamsburg is valid, it would be easy to overlook the power of its cultural pull. According to Wilson,

“Colonial Williamsburg is the most famous design created in Virginia in the twentieth century, and its impact nationwide can hardly be overestimated. From houses to corporate headquarters, from paint colors to interior décor, Williamsburg reproductions appear everywhere.” (Wilson 35)

Its commercial activity can appear relentless. The 1985 edition of Jane Carson’s book could not have come from Colonial Williamsburg (the foundation first published it in 1968) absent a product plug on its frontispiece:

“The wallpaper on the cover of Colonial Virginia Cookery is ‘Williamsburg Apples.’ It is an adaptation of a late eighteenth-century fabric, believed to be of French origin, that was used to make one side of a quilt. ‘Williamsburg Apples’ is available from Katzenbach and Warren. A matching fabric is available from Schumacher.”

Williamsburg Apples.

The vast online store includes an array of expensive fabrics, furniture and furnishings; over a thousand products in those categories alone. Tricorns too, in several styles. The store also sells a lot of excruciating kitsch along with its ambitious reproductions. Poor old Goodwin.

Wilson was writing in 2002 and if the influence of Williamsburg has waned it remains potent. Just this year Charles Royce, the investment banker who seems to own half of Watch Hill and Westerly, Rhode Island, completed a vanity project there by tacking an instant replica accretion of structures ‘over time’ onto what had been the ruin of the eighteenth century farmhouse next to his replicant barn, now furnished in the High Colonial Fantasy Revival Style. It looks like a nice place to live. That is the problem with the Williamsburg style. It is serene, elegant, retrograde and authentic only to the interwar colonial revival. In other words, lovely.

The heritage site itself is less inclined to quality than the manufacturers of its higher end products. The homepage for the “Nation Builders” program looks like a ‘Saturday Night Live’ parody of its reenactors, who include a Washington looking like he just tied one on, a happy slave and young as well as president Jefferson, which risks upending the time and space continuum.

Williamsburg engages in other forms of hokum as well, including gaol tours featuring actors dressed as pirate zombies in the cells. The tours were part of “Blackbeard’s Revenge, a slate of spooky events that included free trick-or-treating” and pumpkin decorating. “The Blackbeard story,” according to Mitchell Reiss, the director of Colonial Williamsburg, “was accurate-ish,” although Blackbeard never got to Williamsburg and probably was not acquainted with the undead. (Zullo)

All heritage sites, however, resort to gimmicks to varying degrees as a means to attract visitors. As Reiss maintains:

“Unless you can get people to come, you can’t engage them. You can’t educate them, and you can’t inspire them.”

As long as Williamsburg distinguishes between Halloween festivities and historical reenactment it is hard to see the harm in the zombie parade on Duke of Gloucester Street (they did that too), and at least when it comes to children, the place is undeniably inspirational.

Reiss has drawn a lot of fire for his stunts, not least by critics who contend that he has made Williamsburg “more of a show than an educational resource,” but that is something like expressing shock that people are gambling in Rick’s Café Americain. Showtimes of one sort or another have been integral to Colonial Williamsburg from its inception. Apparently neither Leon Krier nor Robert A. M. Stern have a problem with the place which in its way represents a precursor of postmodernism. (Huxtable)

In the end, if it is hard to like Williamsburg with its inconsistencies and inexcusable lapses in quality, it is harder to hate it. The scornful Huxtable, who disagrees with the conclusion of “the cognoscenti” that she describes, inadvertently provides a convincing enough defense of the place. It is, they believe,

“ ….a kind of period piece now, its shortsightedness a product of the limitations of the early preservation movement. Within a conscientious range of… deliberately and artfully set limitations, a careful construct was created: a place where one could learn a little romanticized history, confuse the real and unreal, and have--then and now--a very nice time. Knowledge, techniques, and standards have become increasingly sophisticated in the intervening years, and there have been escalating efforts to keep up.”

They could, however, start moving a little faster on the foodways.

Sources:

Anon., “Colonial Williamsburg Historic Foodways Presents ‘History is Served: 18th-century recipes for the 21st-century kitchen,’” http://recipes.history.org/about/ (accessed 15 October 2018)

Anon., The WPA Guide to the Old Dominion (1940), http://xroads.virginia.edu/~hyper/vaguide/williamsburg.htmil (accessed 15 October 2018)

Jean Anderson, Recipes From America’s Restored Villages (New York 1975)

Fergus Bordewich, “Revising Colonial America,” The Atlantic (26 December 1988)

Edward Bruner, “Lincoln’s New Salem as a Contested Site,” in his Culture on Tour: Ethnographies of Travel (Chicago 2004)

Helen Bullock, The Williamsburg Art of Cookery (9th ed., New York 1961; orig. publ. Richmond 1938)

Jane Carson, Colonial Virginia Cookery (Williamsburg 1968)

Alyssa Connell & Marissa Nicosia, “Cooking in the Archives: Bringing Early Modern Manuscript Recipes into a Twenty-First Century Kitchen,” http://archivejournal.net/notes/cooking-in-the-archives-bringing-early-modern-manuscript-recipes-into-a-twenty-first-century-kitchen/ (July 2015; accessed 6 November 2018)

Karen Davis Cutler, Tantalizing Tomatoes: Smart Tips & Tasty Picks for Gardeners (New York 2001)

Alan Davidson et al., The Oxford Companion to Food (Oxford 1999)

Eric Gable & Richard Handler, “After Authenticity at an American Heritage Site,” American Anthropologist New Series vol. 98 no. 3 (September 1996) 568-78

“Deep Dirt: Messing up the Past at Colonial Williamsburg,” Social Analysis: The International Journal of Social and Cultural Practice no. 34 (December 1993) 3-16

John Gonzales, The Colonial Williamsburg Tavern Cookbook (Williamsburg 2001)

Holiday Fare: Favorite Williamsburg Recipes (Williamsburg 2004)

Kevin Hayes, A Colonial Woman’s Bookshelf (Knoxville 1996)

Ada Louise Huxtable, The Unreal America: Architecture and Illusion (New York 1997); http://movies2.nytimes.books/first/h/huxtable-unreal.html (accessed 12 October 2018)

Ashley Jackson, Buildings of Empire (Oxford 2013)

Lisa Jardine, On a Grander Scale: The Outstanding Life of Sir Christopher Wren (New York 2002)

Gil Klein, “They Did the Best They Could,” Colonial Williamsburg Journal (Winter 2015)

Philip Kopper, Colonial Williamsburg (New York 1986)

Carl Lounsbury, “Beaux-Arts Ideals and Colonial Reality: The Reconstruction of Williamsburg’s Capitol, 1928-1934,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians vol. 49 no. 4 (December 1990) 373-89

John Mariani, “Virginia’s Colonial Williamsburg Tightens Its Belt and Innovates for the Future,” Forbes (20 February 2018)

Dennis Montgomery, A Link Among the Days, The Life and Times of the Reverend Doctor W. A. R. Goodwin, the Father of Colonial Williamsburg (Richmond VA 1998), quoted at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Colonial_Williamsburg (accessed 12 October 2018)

Khalil Gibran Muhammad, “Slavery and the American Constitutution,” The New York Times Book Review (21 October 2018)

Blake Perkins, “An Enquiry into the Derivation of Chowder,” Petits Propos Culinaires no. 109 (September 2017)

Steven Poole, You Aren’t What You Eat: Fed Up with Gastroculture (London 2012)

Mary Randolph, The Virginia Housewife (Washington DC 1824)

Sarah Rutledge, The Carolina Housewife (Charleston SC 1847)

M. Catherine Savedge, “The Wren Building at the College of William and Mary; Architectural Summary; Interior Restoration: 1967-1968,” Research Report 195, Department of Architecture Research, Colonial Williamsburg (October 1969), http://research.history.org/DigitalLibrary/Viwe/index.cfm?doc=ResearchReports/RR195.xml (accessed 15 October 2018)

Suzanne Seurattan, “The Wren: You know the building; what about its history?” (22 December 2015), https://www.wm.edu/news/stories/2015/the-wren-you-know-the-building,-but-do-you-know-its-history.php (accessed 15 October 2018)

Andrew F. Smith, The Oxford Companion to American Food and Drink (Oxford 2007)

The Tomato in America: Early History, Culture, and Cookery (New York 2001)

Charlotte Turgeon et al., Favorite Meals from Williamsburg: A Menu Cookbook (Williamsburg 1987)

Carl Van West & Mary Hoffschwelle, “Slumbering on its Old Foundations: Interpretation at Colonial Williamsburg,” South Atlantic Quarterly 83 (2) (1984) 157-75

Robert Zullo, “The future of history: New direction for Colonial Williamsburg met with praise, backlash,” Richmond Times-Dispatch (12 March 2016)