Factual fiction, featuring strange birds, narcotics, romantic foodways, a quack doctor & Things: Part 3 of 3.

Hackneyed and fantastical visions of time.

Reflecting the personal habits of William Kitchiner, Thomas De Quincey discovers that for celebratory rather than quotidian occasions dinnertime diverges from the earlier hour of six or so, from until seven or later (Bridge 16) and, with an obligatory jab at misplaced Irish pretense, all the way to time travel:

“For a more festal dinner, seven, eight, nine, ten, have all been in requisition since then; but we have not heard of any man’s dining later than 10, P.M., except in that single classical instance… of an Irishman who must have dined much later than ten, because his servant protested, when others were enforcing the dignity of their masters by the lateness of their dinner hours, that his master dined ‘to-morrow’.” (De Quincey, “Dinner” 16)

De Quincey refuses to present any of that with anything like clarity; the timeline of the changes he tallies throughout “Dinner” is a construct not his own. “He wrote,” as Chiasson observes, “in defiance of chronology, which he called a ‘hackneyed roll-call.’…. The details of his life” more generally “were like carousel horses, disappearing around the bend and reappearing, in his visions as in his writing, with fresh intensity and vividness.” (Chiasson) “Everything,” Phil Baker explains, “recurs in De Quincey.” (Baker)

A Brahmin bestows his blessing.

Dinner was the exception; while his essay on the conundrums it contained swoops and loops in terms of both topic and time, it does not appear that De Quincey returned to the subject. Nor has the essay attracted the attention of scholars with the exception of Palmer; just recently Diane Purkiss, who gives it scant shrift; and, notably, an enthusiastic Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. He considers De Quincey, in prose that makes him appear concise by comparison,

“the prince of heiroplants… in activity and originality… unsurpassed by any other, including the names of Scott and Dickens, of Wordsworth, Coleridge, Lamb and Southey, of Moore, Byron, Shelley and Keats…. His alchemy is infinite, combining light with warmth in all degrees--in pathos, in humor, in general illumination.”

Longfellow compares De Quincey favorably to Rousseau, another noteworthy confessional writer . According to Longfellow “‘Dinner, Real and Reputed’” displays “great erudition” which however

“is as nothing when compared to the faculty of recombining into novel form what previously had been so grouped as to be misunderstood, or had lacked just the one element necessary for introducing order. To have written these would have entitled Rousseau to a separate sceptre.” (Longfellow)

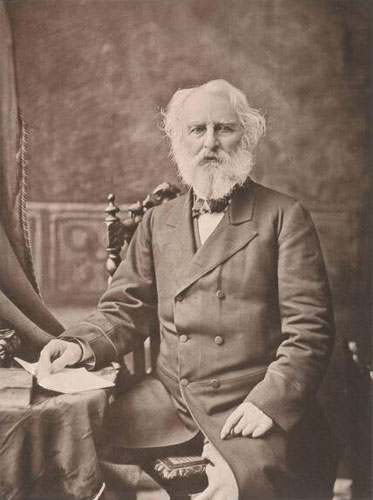

Longfellow, a De Quincey admirer

Robert Morrison, one of De Quincey’s biographers, does not include “Dinner” in the Selected Writings he edited for Oxford as recently as 2019. It is an uncharacteristic oversight. As an admiring Jad Adams notes in his review of the biography, Morrison is an “assiduous researcher” who “has even deciphered the Greek and Latin code in which De Quincey kept records of his masturbation in his diary.” Confession had its limits, even for De Quincey. (Adams) His other recent biographer, Frances Wilson, mentions the masturbation as well but also overlooks “Dinner.”

Time is as nothing.

Before proceeding to empty a bucket of ink on the timing of dinner, a mercurial De Quincey had decided early in the essay that the hour is unimportant to its definition; “upon reviewing the idea of dinner, we soon perceive that time has little or no connection with it…. Time, therefore, vanishes from the equation: it is a quantity as regularly exterminated as in any algebraic equation.” (De Quincey, “Dinner,” 7-8)

But, another paradox, it has paramount cultural, even moral import; “exactly in proportion as our dinner has advanced towards evening, have we and has that advanced in circumstances of elegance, of taste, of intellectual value…. With graces both moral and intellectual; moral in the self-restraint; intellectual in the fact, notorious to all men, that the chief arenas for the easy display of intellectual power are at our dinner tables.” (De Quincey, “Dinner” 16)

Dinner during evening had become even more important than a platform for intellectual display. In De Quincey’s tumultuous, disorienting day it had become prerequisite to maintaining sanity:

“When business was moderate, dinner was allowed to divide and bisect it. When it swelled into the vast strife and agony… that boils along the tortured streets of modern London or other capitals, men begin to see the necessity of an adequate counterforce to push against this overwhelming torrent, and thus maintain the equilibrium…. But for this periodic reaction, the modern business which draws so cruelly on the brain, and so little on the hands, would overthrow that organ in all but those of coarse organization. Dinner it is,--meaning by dinner the whole complexity of attendant circumstances,--which saves the modern brain-working man from going mad.” (De Quincey, “Dinner,” 14)

The point requires repetition (everything recurs in De Quincey): “We repeat that… but for the daily relief of dinner, the brain of all men who mix in the strife of capitals would be unhinged and thrown off its centre.” (De Quincey, “Dinner” 16)

Primus inter pares.

It follows that dinner bears more significance than other human achievement. “The revolution as to dinner was the greatest in virtue and value ever accomplished. In fact, those are always the most operative revolutions which are brought through social or domestic changes.” (De Quincey, “Dinner” 14) Satire aside, those last two points about social and domestic changes sound fair notwithstanding the political upheavals wrought by Donald Trump, Vladimir Putin and their Scottish antecedent in savagery.

A rhetorical De Quincey wonders how the term ‘dinner’ can encompass practices so disparate in time and substance.

“At this moment, what is the single point of agreement between the noon meal of the English labourer and the evening meal of the English gentleman? What is the single circumstance common to them both, which causes us to denominate them by the common name of dinner ?”

It is, however, palpably something; it must take some kind of form. “It is,” De Quincey explains, “that in both we recognize the principal meal of the day, the meal upon which is thrown the onus of the day’s support. In everything else they are as wide asunder as the poles; but they agree in this one point of their function.” (De Quincey, “Dinner” 6; emphasis in original)

That, however, represents more misdirection, because De Quincey demands more. What, then, are “the whole complexity of attendant circumstances” that define dinner in addition to its status as principal meal? De Quincey identifies intersecting components of the movable feast, although not all at once or in discernable order of import.

“The true elements of the idea are evidently these..:--2. That it is the meal of hospitality. 3. That it is the meal (with reference to both Nos 1 and 2) in which animal food predominates. 4. That it is that meal which, upon necessity arising for the abolition of all but one, would naturally offer itself as that one.” (De Quincey, “Dinner” 8)

Six pages away from those four, following more exegesis on ancient Rome, lurks another requisite, less prosaic and more significant than the first quotidian four. It is that “spirit of festal joy and elegant enjoyment, of anxiety laid aside, and of honorable [sic] social pleasure put on like a marriage garment.” (De Quincey, “Dinner,” 14) Each dinner is as epochal for its participant as the singular ceremonial events of his lifetime.

Much later in the century there are even some women at this epochal event.

Much later in the century there are even some women at this epochal event.

A question of trust.

Given his unreliability, it is fair to ask whether De Quincey is a source that Palmer should bank on. The various hours De Quincey ascribes to dinner across time are, however, for the most part consistent with the settings that Palmer visits. As Pocock indicates, “Palmer noted the movement of the time of dinner from 11 a.m. in the reign of Henry VII to 9 p.m. in 1953, the most advanced time yet recorded.” (Pocock xv-xvi) They are not quite right. As noted, De Quincey sets dinner as late as ten o’clock for festive occasions and, for a socially insecure Irish servant, an elusive future that careens unattainably to tomorrow.

Wartime continuity corroborates De Quincey.

Palmer concludes that “the novels of the Waterloo decade are so well agreed on the dinner-hour, and those written by Miss Austen so widely known, that the reader may be spared many accessible references.” (Palmer 37) Oddly enough he does not cite an Austen novel that sets the predominant hour, at least in London. Happily enough he burdens the reader with a few of the other references anyway.

Edgeworth, as Palmer understands “a careful writer with good knowledge of the fashionable world in England as well as Ireland,” sets the dining hour of the Bolingbrokes at 6 pm during 1805 in A Modern Griselda . On returning to the metropolis that same year Lady Nugent, who left an invaluable record of foodways among the English during her time in Jamaica, “found her friends dining at 6 in London and at 5 in the country.” (Palmer 32, 36) Austen corroborates Lady Nugent’s account. In 1803 “General Tilney ( Northanger Abbey ),” someone “incapable of adjustment,” presumably, that is, behind the times, “dined at 5 even in the country--a reminder that Londoners had ways of their own.” (Palmer 37)

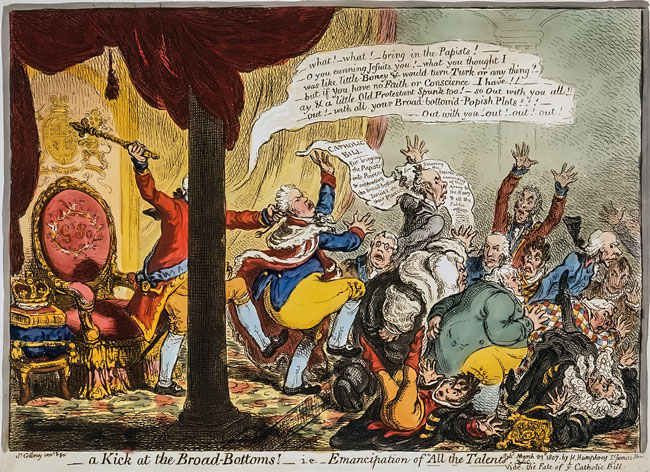

Palmer perceives the nuance that has permeated so many aspects of British life. Thomas Creevey, a prodigious correspondent and one of his nonfictional sources, was a Foxite Whig who served in the shortlived “Ministry of All the Talents,” derided as the “Ministry of All the Bottoms.”

Bottoms up.

Bottoms up.

He enjoyed better luck immediately following Waterloo. Creevey, on holiday in Brussels at the time, scored the first interview with Wellington after the battle and elicited from him the famous assessment that “It was a near run thing. The nearest run thing you ever saw in your life.”

“The aware, the astute, the hobnobbing Thomas Creevey,” as Palmer describes him in lovely, lively prose, “knew very well to rise in society, a man must give the impression not of climbing but rather of finding, even of being helped up to, his own level.” Creevey was, however, no conformist sycophant and Palmer considers him a reliable correspondent. Creevey, he explains,

“seldom failed to note with gratification the slightest departures from the habits and conventions of the fashionable world; he cherished them as signs of sturdy independence, as proofs that nobody could call him a snob; and for the opposite reason we, too, cherish them as evidence of what was normal, of what he was being independent of and hadn’t sold his soul for.”

During the first week of 1811 Creevey wrote his wife from London to say he had begun dining at 6 pm. The hour was novel enough to warrant its serial report. (Palmer 35) By 1822 however Creevey took his dinner at 3:45; Palmer can only wonder why in the absence of a surviving explanation. It is, he observes, an example “of the snares besetting our investigation.” (Palmer 35-36) That year Creevey was only 54 so advanced age does not account for the retreat from fashion.

Palmer does diverge from De Quincey, but only a little, when it comes to Cambridge and Oxford. He finds more flexibility at the outset of the nineteenth century: “The Universities themselves floundered; undergraduates, even at one college, could dine at any time between 3.30 and 5.” (Palmer 36) Palmer identifies neither a specific year nor offers any citation and De Quincey’s is the more detailed description. Deference may be due to him for another reason as well; he was there, at Brasenose College, Oxford, from 1803 until 1808.

Christ Church Oxford Dining Room

Christ Church Oxford Dining Room

A brief interlude for supper.

Palmer, via Austen, Edgeworth and Creevey, also corroborates the quick unsupported account Moss provides about the evolution of supper during the overlapping Romantic and Recency eras, from an ingrained habit to a special event. He does it in superior, sparkling, prose:

“Supper then, like champagne now, was served without comment in the houses of the rich and fashionable, but in Miss Austen’s world it is by no means inevitable, and is apt to mark a rather special occasion or important guest…. It was over by 11 o’clock at Northanger Abbey but that, as the author tells us, was an early household.” (Palmer 38-39)

A later hour appears more prevalent, even in the country: “When the Bolingbrokes were staying quietly in the country with their friends… supper seems to have trickled on till nearly 1 o’clock.” (Palmer 39)

Creevey appears to have encountered a similar scenario in London. He “moved in the upper-eating circles. Rolling from house party to house party… he lets us see what the guests expected, even if they did not always get it.” One host

“satisfied his standards--‘excellent and plentiful dinners [sic], a fat service of plate, a fat butler, a table with a barrel of oysters and a hot pheasant, &c., wheeled into the drawing-room every night at ½ past ten.’ It was not a set meal; it was, rather, a buffet to which the guests could turn as often as their dauntless appetites stormed back victorious from the previous round; and it went on for some time.” (Palmer 39)

No mention, yet, of the savories that had conquered suppertime at the Big Houses and in the clubs of St. James by the Edwardian era, although the oysters come close.

Revival and extension.

Despite the obscurity of Palmer and his work, Oxford University Press found Movable Feasts significant enough to reissue with a new introduction by Pocock in 1983. He expands on the research Palmer conducted three decades earlier. “In the main,” he had warned, “I have confined my attention to gentlefolk, for the reason that there is more evidence about them than about the rest of the population.” (Palmer 3)

“We must look elsewhere,” Pocock explains, “to Mayhew for example, to learn something of

the people who worked through the day and night to produce the silks, the leather, and the lace, those who counted themselves lucky to have dinner at all.” (Pocock xi-xii)

His additional digging reveals that the variety of habitual mealtimes varied even more than the chaos De Quincey and Palmer uncovered. Citing three additional writers of two novels at the outset of the twentieth century, D. H. Lawrence and the Grossmiths who created Mr. Pooter, Pocock traces working and middle class mores instead of the comparatively rarified households that fascinate Palmer. Pocock explains that “we can see how much more complicated Palmer’s task would have been had he attempted a more comprehensive work and considered the evidence which he was less well placed to interpret.” (Pocock xiii)

In those worlds, unlike the subjects of Palmer’s work, dinner was by no means the social event of the day, not, at least, on workdays. Lawrence describes dinner, “their chief meal” for him as well as De Quincey, among mining families. He places it at different times for children (a lot earlier) than for their parents, both “at an hour Oliver Cromwell would have recognized,” half past midday for the children, five o’clock for their father. Their neighbors, a family of farmers, ate dinner at noon. When, however, one of the miner’s sons “began to earn,” in Pocock’s ambiguous phrase, “he encountered eating habits that Arnold Palmer would have recognized. ‘He went out to dinner several times in his evening suit’ and told his mother of ‘these new friends who had dinner at seven-thirty in the evening’.”

Tea is not tea except when it is or is something else.

Then there was the further complication of working class ‘tea,’ which might or might not include any tea and should not be confused with a genteel afternoon “set” or tea, or the more genteel high tea. (Pocock xxv) Tea as a meal “in the late nineteenth century was limited among the mining communities to Sunday afternoon, probably in the wake of a midday dinner.” Neither Palmer nor Pocock can explain “why,” in Pocock’s words, “the word ‘tea’ should replace the socially approved ‘dinner’. No species of tea was the same thing as supper, which was served later, much later, at night.” (Pocock xiv)

That proliferation of British terms and times for eating has caused considerable confusion, especially among outsiders. In one of his entertaining asides Pocock includes a fascist among the misled. On Il Duce: “Mussolini, I am told, used to epitomize his view of the British as a luxurious and effete nation in the phrase ‘a five meals a day people’…. Mussolini’s view was,” he adds, “never true, ” confusing as it did the proliferation of English nomenclature with British culinary practice. (Pocock xxxiii)

Mussolini, confused by British meal nomenclature.

Mussolini, confused by British meal nomenclature.

An observant bunch.

Pocock was a scholar affiliated with Mass-Observation, which has enlisted thousands of people across class lines to survey British habits, attitudes and perceptions on a broad range of topics including foodways. Mass-Observation is a fascinating institution, in common with many others peculiar to Britain. The director of its archive provides a succinct description that Pocock drops in a footnote to his introduction:

“Mass-Observation was founded in 1937 to record, for the purposes of historical research, the day-to-day lives of ordinary people. It does not operate with questionnaires, statistics and samples but depends upon the willingness of volunteers up and down the country to write in their own way once a quarter on suggested topics.” (Pocock xxxiv)

Pocock drew from a number of Mass-Observation participants to update Movable Feasts and describe dining habits from 1952 into the eighties which, however, runs past the Romantic remit of this essay.

Another hoopoe?

In contrast to Palmer and Pocock and in common with the Yale critics, Moss discusses theory in her uneven Spilling the beans: Eating, cooking, reading and writing in British women’s fiction, 1770-1830. Also unlike Palmer and Pocock, Moss maintains that “ Spilling the beans is not about food history.” (Moss 7)

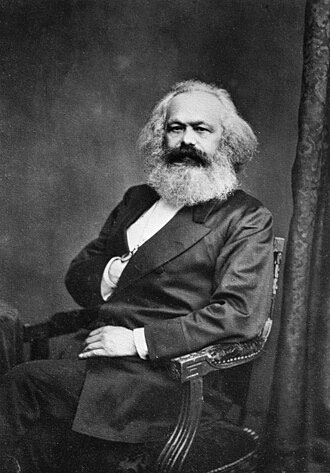

At its outset she admits that she “began with the idea that there are, essentially, two ways in which we might understand food in literary texts,” one derived from Freud and deconstruction, the other “from social contract theories of the eighteenth century via Karl Marx.” (Moss 1, 1-2)

Moss takes a stab at describing both of them, and among other things offers a spectacular misreading of Locke, whom she claims equates food with money. Elsewhere she argues that for Locke, food “is a commodity, or perhaps the commodity… the basis of all economics” and “grounded in need and greed…. Consumption seems to be a form of production. Eating makes property.” (Moss 4, 3)

Those jostling conclusions will surprise anyone familiar with Locke, in common with Burke or Proust more commonly cited than actually read. They would also lend support to his dismissal by De Quincey as unworthy of murder. In fact although he did not consider its relationship to price Locke considered labor, not food, the rationale for private property, basis of economics and source of value.

Marx in the mix

To her credit Moss discovers other methodologies than her initial pair but the loan is modest. Among them ‘feminist-vegetarian critical theory’ may be dismissed. ‘Thing theory’ however, in its less theoretical manifestations, while apparently self-evident, may not be (quite) as fatuous as it sounds, although it appears an implausible explanation for the larger forces that shape human affairs.

It is not just that things matter for practitioners of thing theory; things are the only things that matter. According to the University of Chicago, ironic considering its traditional conservative bias, the doctrine is valid enough and descends from Heidegger via Marxism:

“The forces that define the structure of society, who works and who has political power, who makes decisions, in capitalism are the forces of capital accumulation and value production. These logics [sic;?] are founded on the mystical creation of commodities out of things. So Marx shows us that, in capitalism at least, things are really what shapes society, not people.” (“Chicago School” 4)

Is anything a thing?

So far so good, but the Chicago ‘explanation’ of its intricacies presents thing theory in a murky light that would appear to obscure instead of clarify causation. Bill Brown, the originator of thing theory, ‘explicates’ it in terms of the “process of making thing-ness known” which involves a “primary intuition… that things can exist without subjects but objects are specific creations of subjects.” “Thing” itself

“indicates one of two motions. First, things go beneath objecthood, they are ‘the amorphousness out of which objects are materialized by the (ap)perceiving subject.’ Second, things go above objecthood, they are ‘what is excessive in objects, as what exceeds their mere materialization as objects of their mere utilization as objects…. ’ Either we do not ‘notice’ them, they are mere things, or they are above our perception, like an idol of totem [sic].” (“Chicago School” 3 in part quoting Brown)

Is that something like a relic, ouanga, throne or emoji?

The passage raises other questions. Why does the perception of an object as something other than utilitarian render it ‘excessive?’ That perspective appears arbitrarily judgmental rather than objectively explanatory. Or does ‘excessive’ mean symbolic or merely useful or both or something else? What is ‘(ap)perception,’ why the parenthetical and does it differ from perception per se?

Wrong Thing.

Wrong Thing.

The perception of apperception with reference, however oblique, to De Quincey.

Although OxfordLanguages online considers the term dated, it is a useful if obvious philosophical and psychological concept created by… Descartes. Two of our other acquaintances, Leibniz and Kant, take up the term; the irresistibly named Dagobert D. Runes likens empirical (as opposed to transcendental) apperception to an “inner sense.” (Runes)

With a certain awkwardness Oxford defines apperception (no parenthetical) as “the mental process by which a person makes sense of an idea by assimilating it to the body of ideas he or she already possesses” or “fully conscious perception.” Merriam Webster concurs with Rune in defining its primary meaning as “introspective self-consciousness” and with Oxford in defining its secondary meaning as “the process of understanding something perceived in terms of previous experience.”

Both dictionaries’ definitions are a bit dull and a little deceptive because they do not convey the concept inherent in the term of relativity. AlleyDog.com, the self-styled “Psychology students’ best friend,” offers a fitting example given its name: “a perception would be seeing a dog and thinking ‘That is a dog.’ Apperception would be seeing a dog and thinking ‘That dog looks like my friend Larry’s dog.’” (AlleyDog)

Christopher Ott offers what may be a better if not canine example. To paraphrase him, two children stumble upon a ten dollar bill. The rich one does not consider the bill much money while the poor one considers it a lot of money; each values or devalues the money based on her experience. (Ott)

The parenthetical? Just Brown flaunting his understanding that the term diverges, slightly, from the meaning of ‘perception.’

The great Object v Thing debate featuring the Thingliness of all things.

Whatever the nature of their excess, objects would appear more important than things:

“The quality of ‘objecthood’ as opposed to Heidegger’s ‘thingliness’ is… the quality of things that is created by us as perceiver. The objecthood of an object is internal to us, constituted through the reference and relevance, through its name and use.”

It appears unclear whether ‘internal perception’ of an object is individual and varied or collective and constant, but whatever the case anyone coining the phrase “objecthood of an object” is in for a rough ride outside a flock of hoopoes.

Maybe objects are not that significant; perhaps ‘things’ are paramount after all: “However in thing-ness things are purely out there, unmediated.” To clarify things further, in the same passage Chicago intones: “Thing indicates the ontic and object, the ontological.” “Thing” then also appears not only an object itself rather than something different traveling below or above one, but also a key or the key to perception of the outside world and nature of existence. It is, as Richard Posner might say, a puzzle.

Unmediated, or just ‘out there’ stripped of secondary meaning a thing may be, but its significance, Chicago seems to say, is infinite: “Here ‘thing’ is used to tackle metaphysical questions about our relationship to the world. It is the fundamental question of media going all the way back to Plato and the allegory of the cave.” (“Chicago School” 3)

That sounds like a leap of faith unless Brown and the Thingies have gone all the way and redefined ‘thing’ as some kind of ontological hydra. In that case a new word might have been the better or at least clearer option. Heidegger’s example of a hammer exemplifies the problem of definition, or antidefinition, inherent in thing theory. A hammer is only a thing, he believes, when it is broken, has been rendered nonfunctional. The distinction degrades and distorts the ordinary meaning of the word, which would not appear to explain much of anything.

Neither Oxford nor Stanford provides so detailed an explanation of thing theory as Chicago, which renders their versions more if not completely comprehensible. In common with Chicago, Sarah Wasserman for Oxford traces the origin of thing theory to Brown, specifically his influential 2001 essay in the journal Critical Inquiry and expanded in his 2004 introduction to the collection of essays he edited called, unironically, Things. Wasserman dispenses with most but not all of the Chicago jargon (inevitable, drawn as it is from thing theory itself) to describe Brown’s theory in relatively straightforward terms as “a blend of Marxism, psychoanalysis and phenomenology.”

The essays in Things “consider the force by which objects become fetishes, totems, values, and agents.” They are, then ouanga after all. Instead of discounting all human agency, in Wasserman’s telling, which may be inaccurate, thing theory “is rather a means to explore the dynamics between human subjects and inanimate objects.” Even so, the “second phase” of thing theory that emerges in about 2010 “entailed scholars seeking to decenter the human subject from materialist studies” which sounds a lot like the earlier Annales School championed by Fernand Braudel.

Wasserman joins Chicago in attempting without much success to describe the distinction thing theory attempts to draw between object and subject as well as the relationship between the two things (which may not be things). Wasserman also recounts Heidegger’s notion that when “an object breaks or is misused, it sheds its conventional role and becomes visible in new ways: it becomes a thing” which, however, is not necessarily the same thing as considering the object a fetish, totem, value or agent. (Wasserman)

Stanford dispenses with jargon altogether to explain that thing theory

“gave many literary scholars a new way of looking at old things. For some this included tracing the material histories of objects within books…. For others, it meant pondering the ways that language and narrative reorganize subject-object relations in the minds of readers…. Not simply a way of tracking the fate of snuffboxes, stamp collections, and kaleidoscopes, thing theory allowed scholars to consider what our relationships to these items reveal.” (“Thing Theory in Literary Studies”)

That sounds reasonable enough but raises the question whether thing theory, stripped of the inside baseball, is much of anything at all.

A scholar called Bruno Latour has developed an offshoot, “Actor network theory… founded on a notion of action and agency that allows both people and things to have agency.” (“Chicago School” 4) That is a relief but also some indication that thing theory is one dimensional. If ‘thing theory’ did not discount the significance of human actors then Latour would not have needed to introduce them.

Chicago works on Things.

Chicago works on Things.

A twenty first century scholar tries her hand--again.

Moss offers yet another explanation of thing theory, or attempts one anyway. “‘Thing theory,’” she claims, “considers the ways in which literary texts imagine or admit the subjectiveness of ‘objects’” and “might seem to offer a bridge between… ideas of objects as abjected subjects and objects as transferable value.” (Moss 4-5)

It is not controversial to claim that objects can be subjective, and can carry symbolic significance, although how thing theory differs from ordinary observation remains unclear. A certain difficulty also arises because ‘abjected’ as opposed to ‘abject’ is not a word. ‘Abject’ means either the experience of something bad, a spur to misery, or self-abasing, all of which trigger a similar emotion. Is an ‘abjected’ object a miserable one, or one that instills misery or feelings of remorse or apology? It would appear unlikely.

The irrelevance of things.

Whatever it is, its adherents consider thing theory universally applicable to the analysis of human endeavor. Moss considers applying it to food but decides instead to discard the theory because food, “even when it appears in non-fiction prose, is not material culture. We cannot read food because, like the past, it is not there.” (Moss 6)

Food “is not a ‘thing’ in the sense that… lapdogs, diamonds and books… are things, because food is not an option,” whatever that infers and however that sets it apart, “although at the same time it is more of a ‘thing’ than air or water because of its infinitely variable, and endlessly meaningful, forms.” (Moss 5)

Other commodities--“china, glass and silver” among them--"survive… but food ‘goes off’ in one way or another, its energies passed on to other forms of production.” (Moss 6) But the items other than food she lists also take “infinitely variable, and endlessly meaningful, forms.”

Nor is the perishability of food unique. Lapdogs age and die, books deteriorate, metals corrode, chemicals (and water) evaporate, wood rots; or burns, sometimes to ‘pass its energies on to other forms of production.’

Food need not be perishable either, at least not for a long time. For centuries foodstuffs have been dried, fermented, distilled, pickled, salted and smoked; more recent means of preservation included canning, freezing (with a longer history in colder climates) and freeze drying.

Food encompasses all creation.

Moss further attempts to distinguish food from other substances. In common with money,

“food is an object. Like sex,” however, “it is also a process…. Food is power in material form, both physical power to move a pen and political power to maintain social inequality. It represents love and money and it becomes ordure.” (Moss 7-8)

If food is a lever of power that hardly sets it apart from other tools; clothing, education, industrial capacity, real estate, titles, weapons, wealth itself, so it is difficult to discern why Moss attempts to distinguish it that way. And does it really ‘become’ ordure? Is not ordure so removed from food that is something different?

Moss is by no means consistent in her characterizations of food except to perceive it as the universally dominant concept and commodity. It is the medium of material, psychological, sexual and societal exchange, the obverse approach of the thing theorists who define ‘thing’ down to nearly nothing. Conservative capitalists of the shallower sort consider money the most interesting object in creation because, they claim, it amounts to anything, or everything; it may buy everything. Moss appears to elevate food above money, its potential purchases or anything else in significance, which may account for her incorrect ascription of the perspective to Locke. For her, food would appear to encompass all human endeavor.

Another problem with Theory.

“There are” as a result, Moss adds, “specific, and timely, challenges to literary theory here.” It never becomes clear what those challenges are but at this point it may be worth noting that literature poses challenges to most theory to the extent that theory is often too rigid and one dimensional to accommodate the texts it seeks to interpret.

In her effort to explain what she means about the challenges things get worse in the form of a quotation from Timothy Morton:

“Nevertheless, while historicism uses the ‘real’ as a rhetorical supplement that enriches its analytical observations, post-structuralist work in psychoanalysis and deconstruction posits the real as inaccessible, visible as a gap or an inert presence. Diet studies need… negative dialectics: the encounter of thought with what it is not--non-identity.”

If that is jargon worthy of the Yale School, gibberish perhaps, Moss proceeds to render whatever it is irrelevant to her project: “I do not claim to offer such ‘negative dialectics’ in what follows, but I intend to remain mindful of the challenge.” (Moss 8)

The challenge for her reader is just what approach Moss thinks she has adopted after discussing and sometimes discarding theories to which she also returns. By the end of her introduction the focus apparently has narrowed to a sort of female culinary materialism: “Woman’s goodness inheres in what she makes and sells…. The economics of the body and the literary marketplace come together in the unstable currency of food.” (Moss 43)

Questionable convergences.

What follows is sometimes a stretch. Outrage against women who furtively eat sweet foods “arises from an implicit connection between secret snacking and masturbation, both private forms of bodily self-gratification that seem to work against regulated ways of consuming and (re)producing.” (Moss 20) The linkage of food and sex is not new, but Moss offers no concrete evidence of the putative link between Romantic cakes and autosexuality. Sweet cakes were expensive to bake; eating them in secret does evoke selfish conspicuous consumption and that is a habit those morality tales attempt to discourage.

In connection with “the birth of a new genre,” the popular eighteenth century pregnancy handbook, Moss finds “the implication of reproduction, like cooking, in the burgeoning economy of books.” (Moss 83) The dubious convergence of sexual, culinary and publishing activity appears in an interesting chapter on Wollstonecraft, which incidentally concentrates more on nonfiction, much of it written by men, instead of the womens’ writing that ostensibly concerns Spilling the beans.

Wollstonecraft: Not really a feminist

Wollstonecraft: Not really a feminist

No sex please, we’re mothers.

The chapter should go some way toward defacing the current incarnation of Wollstonecraft as a liberal feminist icon. She harbored, it transpires, a “revulsion at girls’ interest in food” (Moss 126) and obsessed over breastfeeding to the exclusion of intercourse or any other sexual activity. More generally her hortatory writing on pregnancy and maternity is extravagantly oppressive toward women in comparison to the instruction manuals of her male counterparts.

In that sense Wollstonecraft has wandered outside the marketplace. As Moss wryly notes, “presenting breastfeeding as a replacement for sexuality… is not likely to sell books to pregnant young women and their husbands.” (Moss 104)

No breasts please, we’re amoral moralists.

Another guest at Johnson’s table took a different view. At least according to Moss, “Edgeworth views the breast and indeed the rest of the maternal body with suspicion and ambivalence.” (Moss 123) Unfortunately Moss never returns to the point let alone elaborates on it. In further contrast to Wollstonecraft, the childrens’ fiction of Edgeworth commodifies food. “Edgeworth,” according to Moss, “is unique in this genre and period in denying that food has any innate moral content. It is, for her, more like money than like sex.” (Moss 127) The comparison is a little confusing and presents Moss, who conflates food with money and sex, with an epistemological problem she does not address.

Much of what follows about Edgeworth is a labored psychoanalysis of simple morality tales in which selfless sacrifice overcomes “malice, greed and lack of principle” to redress hardship and tragedy. (Moss 134) “Goodness,” in these stories, as Moss puts it in one of her more sensible passages, “leads unfailingly to wealth and badness to economic failure.” (Moss 138)

Self interest or social contract?

According to Moss, Edgeworth is an icy and transactional Ascendancy conservative (despite the biting satire of her class that is Castle Rackrent ) bent on preservation of prevailing realities. Food as metaphor does mark her childrens’ tales but is peripheral to the project, a common denominator that facilitates storytelling across class lines and not much more. Moss herself infers as much in discussing one of the tales without reference to food:

“Even the uncommercial advantages of virtue are presented as a matter of self interest; it is simply more comfortable, more relaxing, to avoid ‘the various embarrassments and terror to which knaves are subject.’ There is no hint that one should espouse honesty for its own sake, perhaps despite hardship or inconvenience. Virtue is not its own reward, but merely the most convenient and reliable source of income and comfort.” (Moss 139)

Whether or not Moss is right about the expedience of decency (Edgeworth called the childrens’ fiction her “Moral Tales”) that is not the case in another story, from The Parent’s Assistant , a collection that Johnson renamed from The Parent’s Friend , a change that angered Edgeworth . (“Maria Edgeworth;” Hall 351) Simple Susan involves the Price family of tenant farmers tormented by Mr. Case, a grasping lawyer of “litigious habits,” no surprise there, and a “suspicious temper.” Both he and his daughter are eager extortionists.

The law is an ass that wants a sheep.

After his conscription into the army (elsewhere Moss misnames it the militia), Susan’s father used their cottage as security to borrow payment from Case for a substitute recruit. The lawyer finds a flaw in the lease that renders it invalid and calls in the loan, forcing Susan’s father to leave for the army after all. Case, who hopes Sir Arthur Somers, the new landlord, will hire him as his agent, tells him that “Price’s whole land [is] at his disposal.” Incidentally the surnames Edgeworth has chosen, while unremarked upon by Moss, are delicious. Case and Price speak for themselves; Somers descends from an old English term for a person of warm disposition. (“Last name”)

Sir Arthur demurs, noting correctly that eviction would render the family destitute. He does, however, ask to see the lease. Case learns that Sir Arthur likes to eat lamb and decides to bribe him with a gift. After his awful daughter tells Case Susan has a pet lamb he visits the cottage to ask her what she would pay to keep her father at home--but for only an extortionate week’s reprieve. Even so Susan says “Anything!--but I have nothing.” (Moss 129-31)

“‘Yes, but you have a lamb,’ said the hard-hearted attorney. ‘My poor little lamb!’ said Susan; ‘but what can that do?’ ‘What good can any lamb do?’ ‘Is not lamb good to eat? Why do you look so pale, girl? Are not sheep killed every day, and don’t you eat mutton? Is your lamb better than anyone else’s, think you?’ ‘I don’t know’, said Susan, ‘but I love it better.’ ‘More fool you,’ said he. ‘It feeds out of my hand, it follows me about, I have always taken care of it; my mother gave it to me.’ ‘Well, say no more about it, then,’ he cynically observed; ‘if you love your lamb better than both your father and your mother, keep it, and good morning to you.’

At this, of course, Susan agrees to take her lamb to the butcher ‘before nightfall’.” (Moss 131, quoting Edgeworth)

Sacrificial lambs, literal and symbolic.

“Against the background of Edgeworth’s usual distrust of sensibility” Moss finds “several ways of reading this encounter:”

“In some ways, Case is obviously right; if Susan is content with meat-eating in general and the consumption of lamb in particular, there is no ideological reason why her emotional investment in the lamb should preclude its slaughter. In this case, Susan’s capitulation may constitute a victory of sense over sensibility that contributes to her maturity and selflessness. She is distressed at the idea of her lamb’s death and consumption, but she is able to override dismay with reason.” (Moss 132)

Edgeworth repeatedly refers to the lamb as a pet because nothing could distress the owner of a pet, especially a child, than its death, let alone being forced to kill it: Simple Susan is, after all, a story for children. The animal as pet, not as food, is the emotional hook Edgeworth selects. That is why, in her detailed biography of Edgeworth, Marilyn Butler does describe the lamb in Simple Susan as a pet while omitting any mention of food in connection with the story, which she finds “not mawkish but touching.” (Butler 160-64, 164)

Animal rights and wrongs.

Case therefore is a long way from obviously right, especially in context. “The attitude of the English towards animals,” as G. J. Renier observes in a serious passage of his satire The English: Are They Human? , oscillates “between extremes of maudlin sentimentality and cruel bloodthirstiness.” (Renier 78) Some of the earliest societies for the humane treatment of animals and vegetarian movements have coexisted in England with murderous blood sports from bearbaiting to foxhunting. Within that paradox pets enjoy a unique position and yet Moss herself neither refers to the status of the lamb nor uses the term in her analysis. Ideology and reason have nothing to do with Susan’s dilemma and the point of the story is that her “emotional investment,” better described as love, should preclude the slaughter of her pet. Placed in position of untenable horror she submits to the penultimate sacrifice.

“Alternatively,” according to Moss,

“particularly in the context of Edgeworth’s dependence on enlightened self-interest as a guiding principle, perhaps it is Susan’s staccato run of unconnected clauses that bears the truth here. ‘It feeds out of my hand, it follows me about; I have always taken care of it; my mother gave it to me.’ The lack of conjunctions in this sentence contrasts with Case’s dispassioned reasoning. Susan has no counter-argument to this demonstration of the animal-loving carnivore’s irrationality except, ‘I love it better’. She cannot explain why the lamb should have taken on human behaviours in her mind. She can only assert, haltingly, that it has. If this is an example of a little peasant who is more than a ‘machine that eats’, then it may be that the truth, here, lies in the semi-colons. It follows her about; she has always taken care of it; her mother gave it to her. This is not just meat.” (Moss 131-32)

The alternative reading may lie farther afield than the first, although at least Moss acknowledges that the lamb “is not just meat.” Still, it remains unclear why she refuses to call it a pet unless she understands that the description would undercut her insistence both sheep and Susan symbolize food. Susan is not irrational in loving her lamb; that itself is the counterargument. Instead of demonstrating why Susan cannot explain her love, the choice by Edgeworth of semicolons to indicate halting speech amplifies Susan’s panicked grief. Her difficultly in responding to Case does nothing to mask her emotions, while nothing in the story more generally indicates that the pet has “taken on human behaviours in her mind.”

A domestic and commercial jack of many trades.

After the encounter with Case Susan, resourceful surrogate that she is, takes on the bookkeeping for the family bread business while continuing to care for her distraught and incapacitated mother. In addition to gathering eggs from a guinea fowl she also does the baking. Elsewhere the reader has learned that Susan collects eggs from a guinea fowl and ferments mead from honey she harvests from the family hive. The family produces all those foodstuffs for sale.

After Susan fetches her younger brothers from school the siblings take her lamb to its intended slaughter, attracting an escort of the village children, who revere Susan for her array of wonderful qualities and festoon the lamb with colorful garlands. (Moss 129, 133)

A butcher with heart.

On arrival at the abattoir the children including the butcher’s son plead with his father to spare the lamb. As it happens the butcher requires no convincing; “‘it’s a sin to kill a pet lamb,’” he thinks, and “any way, it’s not what I’m used to and don’t fancy doing.” To convince Case to accept a different lamb, the butcher bribes him with a gift of sweetbreads. (Moss 133)

“It is the butcher,” according to Moss,

“the man defined by his exchange and equivalence of money and animal life, who insists that Susan’s lamb is outside the ordinary trade and this is explicitly because Susan, ‘is a good girl, and always was, as well as she may, being of a good breed and well reared from the first.’” (Moss 133-34)

Moss considers his reasoning both bestial and transactional but somehow also outside market calculations:

“Particularly coming from the butcher, this reference to Susan’s ‘breed’ and ‘rearing’ seems to conflate her with the animals who come to the slaughter. It is as if Susan herself, being a good girl, has an equivalency value. Susan is so much like the lamb that the lamb is like Susan, unsuitable for human consumption…. ”(Moss 134)

The power and place of pets.

Any such reading must rely on anachronism that verges on parody. Good breeding and rearing were common enough compliments for admired families during the Romantic era and their use by Edgeworth in no way connotes animal husbandry; the Prices are good people. It is not, however, by any means explicit that he saves the pet only because of her upbringing. The butcher determines to save the lamb because it is a sin to kill a pet--he never does or would do that--not because he equates Susan with sheep. She has no ‘equivalency value’ to the butcher; along with everyone else but the Cases he likes her because she is virtuous and kind, which of course helps her cause.

Susan “owns the means of production,” Marxist rhetoric, of food and drink--that bread, those eggs, the mead, maybe sheep--but according to Moss instead endowing her with power “all this productivity identifies her uncomfortably closely with the commodities she produces. It seems that part of the virtue of the good girl who produces,” more Marxism, “is to invest herself so thoroughly in what she makes for others to consume that they are almost invited to partake of herself. Take, eat. This is my body, given for you.” (Moss 134)

Moss makes no attempt to reconcile her contradictory conclusions. In her reading Susan is “unsuitable for human consumption” while her flesh may be eaten. All this overlooks, or overrides, the obvious. Susan is unsuitable for human consumption because cannibalism revulsed Edgeworth and the English, not because she keeps a pet or sells food.

Hunger and rectitude.

Moss expresses surprise that even though in her reading Simple Susan is all about the food and its attendant power dynamics, destitution let alone hunger is not at issue, “even in metaphor. The mother and children dread the loss of the husband and father, but the dread is expressed in exclusively affective terms…. The pure of heart are above hunger…. ” (Moss 135)

In the society inhabited by Edgeworth’s British (as opposed to a minimal Irish) audience hunger was not in fact a persistent problem, and she could hardly conjure a compelling world for her reader if it were unrealistic. “Literary criticism,” Moss recognizes elsewhere, “particularly where it is concerned with children’s literature, sometimes assumes that instabilities in food supplies or employment were sufficient to tip large numbers of the poorest British people into starvation. The evidence from food and agricultural history suggests that this is not so.” (Moss 10) The Prices are not the poorest; their precarity results from the conniving of Case. It is not purity of sentiment that spares them starvation but rather the economic reality of their era.

If however the pure of heart are above hunger, what does that imply about the centrality of food to the narrative of “Simple Susan?” That is another example how Spilling the beans lacks consistency and coherence on any number of counts.

The Big House to the rescue.

Toward the end of the story Sir Arthur cements the rescue begun by the people of his town. In error Case sends him the wrong lease, his own, which turns out to be flawed too. When he learns of the Case machinations the benevolent landlord evicts the lawyer and banishes him.

From all this Moss concludes that for Edgeworth: “A social order in which virtue meets its just deserts relies on a bucolic idyll of benevolent aristocracy and dutiful peasants, in which there is no place for Attorney Case’s pretensions of independence. The poor make food for the rich to eat and the rich give the poor money for food. Rich and poor feed on each other in a cycle of mutual alimentary independence confined by the corporate and individual relation to food.” (Moss 134)

Not so fast.

At this point Moss errs in matters of fact as well as anachronism. If Spilling the beans is not about food history it still manages to get history wrong. Sir Arthur is no aristocrat; he has no title. Instead Sir Arthur belongs to the English gentry associated with industry and bluff common sense, a contrast to the popular perception of feckless aristocracy spendthrifts, then as now.

His tenants are anything but peasants. The butcher of course is a tradesman while the Prices are not mindless subsistence farmers who pay rent in kind. Nor are they poor.

The cash does not flow a single way. Instead the nexus of exchange involves rent money from tenants to lord and from lord to producer, whether artisan, farmer or both. In England, a commercial revolution preceded the industrial revolution and cottage economy preceded factory scale within the industrial revolution itself. Consider the Prices. In addition to working their land they keep livestock, bake bread and brew mead. They and the butcher represent the sturdy and celebrated independent yeomen of English folklore, not a species of European peasantry.

Case fails not for his pretensions to independence--it was an age of chutes and ladders before the stratification of the Victorian era, in which the humble might rise and the rich could fall-- but because he is a bad actor working to subvert the system of mutual obligation that binds the country, a system based on custom as much as on law. In any event Case does not scrabble for independence; the purpose of his scheming is the award of a dependency within the established order, the office of agent to Somers.

Pragmatic enlightenment.

All of that comports with the Edgeworth ideology, which is not, however, so simpleminded as Moss portrays it. Chris Fauske and Heidi Kaufman highlight her “sensitivity to nuance, her recognition of her own class’s tenuous claims of legitimacy, and her awareness of the contradictions of English ideals of civil society and English practices in Ireland.” (Kaufman & Fauske 24)

It bears noting that Edgeworth, a “tough businesswoman” who acted as her own agent at Edgeworthstown for thirteen years and oversaw its management for decades, had no illusion about the difficulty of rural life. (Keown) In Helen , an 1834 novel, Claire Connolly maintains that “Edgeworth reverses the expected moral, making quiet rural simplicity seem more dangerous than the buzz of metropolitan life.” (Connolly) In her Essay on Irish Bulls Edgeworth describes “‘propaganda, libel, perjured evidence, fanaticism, intolerance, rumor, sensation-mongering, and incitement to violence and to national or sectarian hatred’” on both sides of the divide. (Kaufman & Fauske; citation omitted)

In 1913 an awed former servant recalled that during the famine that began in 1847 “the great writer, was then old and feeble but her heart went out to the poor and afflicted… tenants on the Edgeworth estate.” (Connolly) At age seventy nine Edgeworth, leaning on a cane and stopping at intervals to catch her breath, personally distributed food, turf for fuel and clothing to the cottiers on the estate. (“Maria Edgeworth”)

Her efforts did not go unrecognized. In the midst of the famine two barrels of flour arrived at Edgeworthtown from Boston. Their address: “To Miss Edgeworth, for her poor,” nothing more. “There are,” Kaufman and Fauske conclude, “a variety of readings possible in that message. Maria would have happily provided several of them.” (Kaufman & Fauske 26)

An original writer and according to Edwina Keown “the first novelist to examine human society through focusing on the local,” Edgeworth has been credited with creation of “the regional novel, national tale, socio-historical novel, and big-house novel.” She exerted considerable influence in her day. Scott acknowledged it and modelled Waverly on her novel The absentee ; Austen idolized her work. (Kaufman & Fauske 25; Keown)

Her interests were catholic; the scientific experimentation and innovation of those Lunar men, economics, education reform, European history, law and literature. “Edgeworth’s theoretical education,” as implied by her management of a sprawling estate in politically turbulent not to say revolutionary times infers, “was counterpointed with a practical one, as her father’s assistant in estate management and educating her younger siblings.” She was the second of twenty two surviving Edgeworth children. (Keown)

In addition to her politically radical father, who supported the French Revolution and was nearly lynched by a mob of paranoid fellow protestants during the Rebellion of ’98, Edgeworth was “inspired by English and French literary culture (she spoke fluent French), Scottish Enlightenment thought and Irish life.” (Keown; Connolly)

Her own politics were, marginally, more conservative. She and her father both probably sympathized with the United Irishmen and did oppose the 1800 Act of Union that abolished the Irish Parliament by bribing a majority of its membership. (Kaufman & Fauske 19, 13) Neither of them, however, would tolerate relinquishing their land to its catholic tenants.

“Generous and enlightened paternalism,” Valerie Pakenham explains, “was in Maria’s view… the best insurance against social revolution,” but now the Enlightened twist--“until education had percolated to the majority.” (Pakenham) That majority was catholic and instead of blind allegiance to an established order, Edgeworth supported its emancipation but not O’Connell, whom she considered dangerous. Notwithstanding his Roman catholicism he was incidentally, in contrast to Edgeworth, a rackrenting landlord.

Moss declines to address or does not comprehend any of Edgeworth’s intellectual traits, again while overstating her interest in food as social mechanism.

Out of clarity, murk.

Moss oscillates between arguing that Edgeworth lacks a moral edge in her morality stories and inferring that the restrained food consumption is a sort of Calvinist marker of virtue, as she does in her conclusion about the didactic nature of the childrens’ fiction. “Those who are good with food are also both good and good with money, and the reverse is also true…. There is no space in Edgeworth’s work to separate consumption, production and morality.” (Moss 159) It is typical of the overreaching muddle that characterizes Spilling the beans.

The single page index is an embarrassment to the publisher, Manchester University Press.

Sources:

Jad Adams, “The English Opium Eater by Robert Morrison,” The Guardian (8 January 2010)

Anon.,

“Apperception,” AlleyDog.com ,

https://www.alleydog.com/glossary/definition.php?term=Apperception (n.d.)

(accessed 13 February 2023)

Anon.,

“Last name: Somers,” SurnameDB , https://www.surnamedb.com/Surname/Somers (n.d.) (accessed 27 March 2023)

Anon.,

“Maria Edgeworth,” The Maria Edgeworth Centre , www.mariaedgeworthcentre.com (n.d.) (accessed 28 March 2023)

Anon., “thing,” The Chicago School of Media Theory , https://lucian.uchicago.edu/blogs/mediateory/keywords/thing/ (n.d.) (accessed 22 November 2022)

Anon., “Thing Theory in Literary Studies,” Stanford Humanities Center: Arcade , https://shc.stanford.edu/arcade/colloquies/thing-theory-literary-studies (“updated”) (accessed 22 November 2022)

Anon., “Thomas De Quincey, 1785-1859,” The History of Economic Thought , Institute for New Economic Thinking, http://www.hetwebsite.net/het/profiles/quincey.htm (n.d.) (accessed 13 December 2022)

Phil Baker, “Guilty Thing by Frances Wilson review--a superb biography of Thomas De Quincey,” The Guardian (23 April 2016)

Eric Banks, “Land of the Nod,” Bookforum (Sept/Oct/Nov 2016)

Maxine Berg, Luxury and Pleasure in Eighteenth Century Britain (Oxford 2005)

Tim Blanning, The Romantic Revolution (London 2010)

George Clement Boase, “Kitchiner, William, M.D.,” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 1885-1900 , https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Dictionary_of_National_Biography,_1885-1900/Kitchiner,_William (n.d.) (accessed 21 February 2023)

Fernand Braudel, Civilization and Capitalism , 3 vol.s under separate subtitles (Berkeley 1979)

Tom Bridge & Colin Cooper English, Dr. William Kitchiner Regency Eccentric Author of the Cook’s Oracle (Lewes Sussex 1992)

Bill Brown (ed.), Things (Chicago 2004)

Jo Buddle, “An eccentric epicurean: the life of William Kitchiner (1777-1827), The Cookbook of Unknown Ladies , https://lostcookbook.wordpress.com/2013/06/11/eccentric-epicurean/ (6 November 2013) (accessed 5 February 2023)

Frederick Burwick, Thomas De Quincey: Knowledge and Power (New York 2001)

Marilyn Butler, Maria Edgeworth: a literary biography (Oxford 1972)

Colin Campbell, “The Tyranny of the Yale Critics,” The New York Times Magazine (9 February 1986)

Dan Chiasson, “Hell of a Drug,” The New Yorker (17 October 2016)

Claire Connolly, “Maria Edgeworth was a great literary celeb. Why has she been forgotten?” The Irish Times (26 January 2019)

Theodore Dalrymple, “His gastronomical practice,” British Medical Journal vol. 345 no. 7869 (11 August 2012) 35

Elspeth Davies, Dr Kitchiner and the Cook’s Oracle (Durham 1992)

Tristan de Lancey et al , Strata: William Smith’s Geological Maps (London 2020)

Thomas De Quincey, “On Murder, Considered as an Art Form,” (North Haven CT 28 November 2022; orig. publ. 1827)

“Dinner, Real and Reputed,” http://www.authorama.com/miscellaneous-essays-6.html (accessed 1 December 2022); orig. publ. Blackwoods no. xlvi (December 1839)

Colin Dickey, “The Addicted Life of Thomas De Quincey: Chasing the dragon into a new literary realm,” Lapham’s Quarterly (19 March 2013)

Michael Dirda, “The fascinating life of an English writer, essayist and ‘opium eater,’” The Washington Post (30 December 2010)

Bonamy Dobree, English Essayists (London 1964)

Kenneth Forward, “‘Libellous Attack’ on De Quincey,” PMLA vol. 52 no. 1 (March 1937) 244-60

Neil Edmund Bain Halliday, “Fatal Consequences: Romantic Confessional Writing of the 1820s, unpbl. PhD thesis (Univ. Birmingham October 2019)

Daisy Hay, Dinner With Joseph Johnson (Princeton 2022)

Rosemary Hill, “Spaghetti Whiplash,” London Review of Books (17 November 2022)

Richard Holmes, The Age of Wonder (New York 2010)

Giovanni Iamartino, “At table with Dr Johnson: food for the body, nourishment for the mind,” in Francesca Orestano & Michael Vickers (ed.s), Not just Porridge: English Literati at Table (Oxford 2017) 17-34

Jamie James, Eating Opium and Writing Intoxicating Prose,” The Wall Street Journal (28 October 2016)

William Jerdan, Men I Have Known (London 1866)

Paul Johnson, The Birth of the Modern (New York 1991)

Heidi Kaufman & Chris Fauske (ed.s), An Uncomfortable Authority: Maria Edgeworth and Her Contexts (Newark DE 2004)

Edwina Keown, “Edgeworth, Maria,” Dictionary of Irish Biography , http://www.dib.ie/biography/edgeworth-maria-a2882 (n.d.) (accessed 27 March 2023)

James Ker, “Nocturnal Writers in Imperial Rome: The Culture of Lucubratio,” Classical Philology vol 99 no 3 (July 2004) 209-42

William Kitchiner, The Cook’s Oracle (London 1817)

David Knight, “Davy, Sir Humphrey, baronet (1778-1829),” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford 2004)

Gilly Lehmann, The British Housewife: Cookery Books, Cooking and Society in 18th-Century

Britain (Totnes, Devon 2003)

John Gibson Lockhart, “The Leg of Mutton School of Prose. No. I. The Cook’s Oracle , Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine vol. X (August-December 1821) 563-69 (writing as ‘Peter Morris’), Peter’s Letters to His Kinsfolk , 3 vol.s (Edinburgh 1819)

Robert Morrison The English Opium-Eater: A Biography of Thomas De Quincey (New York 2012)

The Regency Years (New York 2019)

(ed.) Thomas De Quincey: Selected Writings (Oxford 2022)

Sarah Moss, Spilling the beans: eating, cooking, reading and writing in British women’s fiction, 1770-1830 , (Manchester Lancs 200)

Christopher Ott, The Evolution of Perception and the Cosmology of Substance (Bloomington IN 2004)

Valerie Pakenham, “Introduction,” Maria Edgeworth’s Letters from Ireland (Dublin 2017; Kindle edn. N.p.)

Arnold Palmer, Movable Feasts (Oxford 1952)

Blake Perkins, “An Enquiry into the Derivation of Chowder,” Petits Propos Culinaires no. 109 (September 2017) 32-67

“London Taverns and the Dawn of the Restaurant Age,” Petits Propos Culinaires

>121 (November 2021) 85-109

Diane Purkiss, English Food: A People’s History (London 2022)

Brian Rejack, Gluttons and Gourmands: British Romanticism and the Aesthetics of Gastronomy , unpubl. dissertation, Vanderbilt University (Nashville 2009)

G. J. Renier, The English: Are They Human? (London 1931)

Lee Sandlin, “Seductively Dangerous: Without Thomas De Quincey there would have been no James Frey,” The Wall Street Journal (11 December 2010)

Robert McG. Thomas, “René Wellek, 92, a Professor of Comparative Literature, Dies,” The New York Times (16 November 1995)

Jenny Uglow, “The Reader of Rocks,” The New York Review of Books (11 March 2021)

Sarah Wasserman, “Thing Theory,” Oxford Bibliographies , https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/view/document/obo-9780190221911/obo-9780190221911-0097.xml (24 June 2020) (accessed 22 November 2022)

Frances Wilson, Guilty Thing: A Life of Thomas De Quincey (New York 2016)

Simon Winchester, The Map that Changed the World (New York 2009)