Two contrasting cookbooks hot off the press, from April Bloomfield & Brian Yarvin.

Two contrasting cookbooks hot off the press, from April Bloomfield and

Brian Yarvin.

The highly awaited debut book from April Bloomfield has appeared, albeit ghosted by J. J. Goode. Bloomfield is the celebrity chef of the hour, at least in New York, and unless you fly with the luvvies you may wait hours for a table at The Breslin and cannot land one at The Spotted Pig.

Do not mistake this woman as a product of hype. She works hard and can cook. Her resume is beyond reproach; Rowley Leigh, Ruth Rogers and Rose Gray, Simon Hopkinson. The book itself begins with a refreshing revelation of failure, some meatballs she does not like. She is honest enough in the admission of a high school preference for pints over page-turning and in her reference to “my fussy recipes.” Earthy and sensual too; stints at the stove can make Bloomfield “go all funny in the knickers.” What more could we ask?

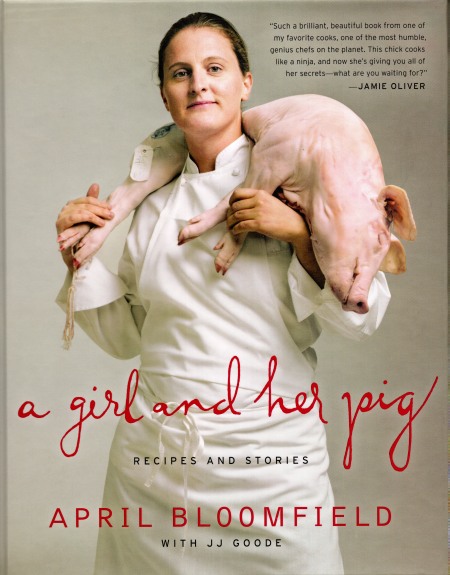

Perhaps for a little controversy; A Girl and Her Pig has not appeared without it. The girl on its cover appears with that pig, quite dead and draped across her shoulders, and good for her too; the piously enraged food prigs ought to know what we eat rather than sweep the evidence away. Once we recognize that those chops and steaks and feet once were alive it gets harder to countenance the torture that is industrial agriculture.

The book bears the subtitle “Recipes and Stories,” which gives a good hint to its focus. It is published by Ecco, and the house deserves a cheer for its production values. The book is illustrated with the usual color spreads of food photography but also with winsome drawings by Sun Young Park. To her credit, Bloomfield not only acknowledges the role of Goode but also gave him the ‘Forward’ to sign; to his, Goode has caught the lovely voice of a quiet working class girl from Birmingham who modestly has made it to the top.

If much about the stories will not be unknown to dedicated trackers of the bold and the new, they are nonetheless soothing and nice. If Bloomfield can make it and keep her level charm, then maybe so could we. And that has got to be the marketing premise chosen for A Girl and Her Pig. It will fly off of shelves but not necessarily into kitchens: Few of its readers are likely to cook much from here. The book is aspirational rather than realistically didactic in its fastidious and complex recipes that require any number of high-end elements.

That is no bad thing; people will enjoy the prose and pictures, and the ambitious among us may even give some dishes a turn. One of them, a beef and blue cheese pie, ought to be among them. Bloomfield selects short ribs for stewy beef, like Susan Goss. She confides that she has “fallen for the funk of Bayley Hazen, a fantastic blue cheese made by Jasper Hill Creamery in Vermont” to the extent she calls the recipe “Beef and Bayley Hazen Pie.” That entails some inadvertent irony; when the PR people previewed the instructions and their blurb on the cheese at ‘Tasting Table’ they omitted the Bayley Hazen from the recipe. Happily the book itself includes it, although in honesty we should note that pretty much anything blue would do.

In a superb example of English understatement, Bloomfield notes that her recipe “might look a little bit elaborate;” in an equally instructive transformation of necessity into virtue, she adds that you can assemble some of its elements the day before you serve the pie. You are going to find some pig’s feet and simmer ‘Sticky Chicken Stock’ with them for at least five hours (recipe provided in the “Cooking School” chapter misplaced at the end of the book) and chill your filling overnight. It in turn will have taken some three hours to build.

You will need a suet crust but may use a springform mold, which should provide encouragement. It makes a pretty pie that tastes as good as it looks but beware: Bloomfield herself looks weary, the lot of a chef, in the sequence of photographs that depict her during assembly.

The beef and blue is a classic British dish, but Bloomfield ranges past the British idiom much of the time. That is fine with the Editor; innovation breeds the new classics, and British foodways have a lively history of promiscuity. We find chimichurri for chops, a summer succotash and bottarga.

A chilled crab trifle takes the old potted crab to new refinement, with swirlings of red tomato and retro green goddess. Like the pie, the recipe itself refers to recipes so prepare to take some time.

Back to the British bent, Bloomfield tucks anchovies into all kinds of meat and describes a postmodern pea soup; she prefers frozen Bird’s Eye babies to fresh, just like us! By now we know that her curry will be complex; appealing too, with all kinds of citrus and pineapple too (the influence of Susan Spicer?).

In sum, this is an altogether lovely book that humbly requests the best of its readers with an open and gentle respect.

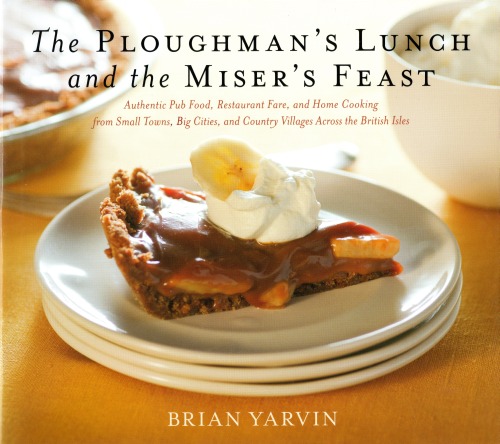

Brian Yarvin, author of The Ploughman’s Fare and the Miser’s Feast--an excellent title--sounds like a kindred soul of Bloomfield and bfia alike. The dedication of his cookbook tells all: “For the farmers, food vendors, and cooks of Great Britain--the unsung heroes of an unsung cuisine.” So they are, and so it is, as we repeatedly claim in these pages.

After so promising a start, however, the book lurches south. About a hundred recipes jostle for space with more than double the number of photographs; this is a volume typical of our time. There is nothing really new here and any number of other books provide a better introduction to British food.

Yarvin recounts the transformation of British foodways over the last two decades but contends that “none of my British friends will admit that their vast food revolution actually happened.” (Yarvin viii) As anyone who actually has visited Britain over the last twenty years would attest, the claim is implausible at best.

He attempts to elaborate on this unconvincing theme by confusing tradition with novelty. On the one hand,

“when my British friends heard that I wanted to write about the traditional foods of their country… they were a bit shocked--and maybe a bit embarrassed…. Yes, they blushed [?] when I mentioned the great seafood, meats, and produce, or the joy of a Sunday afternoon roast beef platter at a rural pub. They admitted the existence of interesting local specialties like pasties and oatcakes.” (Yarvin x-xi)

On the other, “only now are they coming around to the idea that all these foods and dishes make up a fresh, new and vibrant food culture.” (Yarvin xi)

Implausibility and contradiction are not the only problems. Much of Yarvin’s writing is slapdash in both style and analysis; there is little that is either fresh or vibrant about it. Much is simply silly:

“There comes a point when you have enough experience with British food to know that the name of a dish doesn’t necessarily tell you what’s inside. So when I first saw rag pudding on a café menu a few years ago, I didn’t think for even a second that I would be eating rags.” (Yarvin 96)

It is difficult to envision the most doltish diner anticipating the ingestion of fabric scraps; ‘rag’ is simply northern slang for the pudding cloth that once was ubiquitous to the British kitchen.

Yarvin only states the obvious and muffs his opportunity to discuss the dish. The term is associated primarily with Lancashire and particularly Oldham or Manchester. It may or may not refer to ‘the rag trade;’ Lancashire was the first great center of textile production in the world and Manchester justifiably earned its nickname of Cottonopolis early in the first Industrial Revolution. ‘Rag pudding’ itself can refer to any savory suet pudding boiled in cloth; in Oldham it appears most commonly filled with chunks of steak and kidney and in Manchester with ground beef.

Yarvin’s recipe is minimalist and appears to have been lifted straight from www.wikihow.com. It has an Oldham filling of chuck, kidney and onion seasoned with salt and pepper, nothing else. This is cheap and homely comfort food that could stand the addition of herb and stock, a little Worcestershire and a scatter of mushrooms.

We get a fragment of howtowdie; Yarvin does not appear to realize the Scots chicken dish always goes to table with drappit, or poached, eggs and spinach. He does stuff the bird properly with an oatmeal mixture but fails to call it skirlie and tops the breast with intrusive and unwelcome needles of dried rosemary.

Other errors abound. Faggots should not look like meatballs; a Lancashire hotpot should house some kidney but stout and pork do not an ‘Irish hotpot’ make; ‘Scottish’ curry does not refer only to rabbit and restaurant curries do not get spicier as you travel north through England.

There is a sidebar on ‘onion cuisine’ in “The Curry Shop,” a welcome listing of nine recipes. Apparently unaware either that onions are indispensible to virtually every cuisine on the planet or that curries are authentically British, Yarvin imparts the incongruous misinformation that “[m]any Indian dishes, even these Anglo versions, are based on the slow cooking of lots of onions. Accept it, fill your kitchen with wonderful smells, and enjoy the rewards.” Do people really fear the onion?

Yarvin breezily asserts that “curry became British… [a]t least fifty years ago” and speculates without citation that it originated in the cramped galleys of Bangladeshi fishing boats. (Yarvin 102) But curry as we know it did not ‘become’ British; it was invented by the Raj. Scotland contributed a disproportionate cohort to the administration of empire, and so evolved its own discernible variation on the curry theme. Nor is the arrival of the dish in the British Isles a phenomenon of the twentieth century. In fact curry recipes with a decidedly British cast abound in eighteenth-century cookbooks and manuscripts.

There is more of the same to lament but no point in piling on.

Others may concur in our criticism of The Ploughman’s Lunch and the Miser’s Fare. The Editor got her copy at The Strand in Manhattan for half the list price of $27 within days of its publication.

Note:

Our Appreciation of the pudding cloth appears in our archive at Number 2.