Downton Abbey & the drive for ratings, featuring a review of the Unofficial Downton Abbey Cookbook by Emily Ansara Baines.

The Editor is late, as usual, in seizing the main promotional chance. Now that its third season is behind us, however, she finally has gotten around to a consideration of Downton Abbey. Not that she deserves any credit for the tie-in; rather, the tracking statistics provided by the britishfoodinamerica hosting service indicate that a lot of people have begun reaching the site because of the soap.

Downton Abbey

Or so we infer; our essays and recipes about Edwardian glamour cooking are attracting a historically disproportionate share of readers, and ‘lamb chops portmanteau,’ a recipe with an unusual name that Mrs. Patmore prepared during an episode, has become the most popular search term directing readers to the bfia website. An unusually high proportion of readers also have reached us of late through the website of KQED, the San Francisco PBS outlet that not only broadcasts Downton Abbey but also boasts a particularly strong commitment to programming that is related to food.

Nobody would argue that britishfoodinamerica enjoys much of a profile on Google or any other search engine. Searches seeking information about subjects that bfia covers rarely reveal the site in the top ten or even twenty results unless the topic in question is extremely obscure, and then nearly nobody is searching for it anyway.

The motivation for this note therefore is marketing. In an effort to make it easier for devotees of Downton to find us, we have posted popular Edwardian items from our archive on the bfia homepage.

Downton Abbey is, on a superficial level, something anomalous. It is a contrived and shallow period drama with ludicrous plotlines and unlikely liaisons, and none of the skin that helps drive ratings for cable programming like Californication, Game of Thrones or Shameless. And it is the biggest hit in the history of American public television.

That of course is not so surprising. The writers are good (they have a sly sense of humor), the costumes pretty and the Big House itself is a star, upstaged only by Maggie Smith having the time of her life. We like these people too, and find ourselves rooting for them, even the stock ogre O’Brien or cardboard conniver Thomas, because everybody on the show has a human if not necessarily humane side. It has a PBS precedent too, in Upstairs Downstairs which, despite its own undeniable appeal, lacks the sizzle and pop of the Crawley saga. Downton is so much fun.

There is more in play than all of that. Downton is set in an era like our own, of rapid social, demographic and technological change, not to mention economic uncertainty. However removed our experience may be from the life lived by a hereditary grandee or his butler, we empathize with their confused and halting attempts to grope a way between a fading world and its frightening future. Downton has an essential element of tragedy too; we all know how this ends, and it hardly will wind up in the metaphorical sunlit uplands of the warm south. The great estates of deferential servant armies, tenant farmers and white ties have taken the route of the eight-track.

Downton is anachronistic in many respects but feels so real because details ring true; the costumes and settings, cars and not least the food, which will be considerably less familiar, at least to most Americans, than the other props.

The great Marcel Boulestin cites the description of one meal by Vita Sackville-West, who knew firsthand what the aristocracy ate, in The Edwardians:

“The dinner is to consist of turtle, followed by no other fish than white-bait, followed by no other meat but grouse, which are to be succeeded simply by apple fritters and jelly, pastry being on such occasions quite out of place. With the turtle, of course, there will be punch, with the white-bait, champagne, and with the grouse, claret. I shall permit no other wines, unless perchance a bottle or two of port, as I hold a variety of wines a great mistake…. ”

“Which,” as Boulestin himself observes, “is all very noble and sound.”

As Lydia Slater explains in “Dinner is Served… upstairs and down: The recipes from the original TV series are as irresistible today as they were in the Seventies,” “the Edwardian era was the last great hurrah for English cookery” ((London) Daily Mail of 15 January 2011), at least until its relatively recent revival anyway. She provides some color to her account, noting that:

“An Edwardian cook would be expected to know the different cuts of mutton and the common varieties of sheep, the difference between a Berkshire, a Chinese and a Cumberland pig, and how to recognize a good piece of beef.”

She adds that when Cassell’s Shilling Cookery appeared in 1910, it included 370 pudding recipes; newly created dishes got named for “a major event” like the victory at Alma or historical figures like Asquith.

They really are eating Edwardian food at Downton Abbey before as well as after the Great War. This is a conservative world, slow to accept change but hardly ossified either. That is reflected by the food, which evolves between the wars much as Arabella Boxer and others have postulated it did, with not only a growing awareness of culinary cultures beyond Faux French, but also an emergent reacceptance upstairs of the traditional English foodways that never did disappear downstairs.

The evocation of foodways in Downton is all the more impressive--and effective-- because we hear about it more than actually see it. Imagination is a powerful weapon that the writers of Downton deploy to impressive effect.

Tie-ins, not to say free riders, inevitably follow a hit and Downton Abbey is no exception. Emily Ansara Baines, author of the Unofficial Downton Abbey Cookbook, obviously exhibits more marketing acumen than the Editor. The book itself is schizoid leaning to certifiably mad. It includes a good range of Edwardian preparations (although the kedgeree should include smoked, not fresh, haddock) that are easy to follow.

It also contains inexcusable anachronisms like ‘Edwardian Chicken Tikka Masala,’ that she describes as a “soup that arrived on the British culinary scene around 1903, when Edward VII was proclaimed Emperor of India.” The dish, however, is not a soup; it did not exist until the second half of the twentieth century; and Edward merely succeeded to the title of emperor when he ascended the throne. Victoria had been created Imperatrix by Disraeli on the first day of 1877 following enactment of the Royal Titles Act in 1876. What follows is worse: “While there is great debate over the ethics of such a proclamation, the deliciousness of this dish was never in doubt!” Exclamation points, incidentally, abound in Unofficial Downton.

Baines refers to the Slater article but did not benefit from it. It states, among other things, that the Edwardians considered vegetables medicinal and boiled them silly. The Unofficial Cookbook, however, includes any number of crisply cooked vegetables and raw salads, including a spinach salad straight from the 1970s. Baines, however, does not much notice all those puddings beloved of Edwardian diners; there are only five in Unofficial Downton and two of them are variations of the same thing.

When the author attempts to tie dishes to characters the results are risible and also repetitive. Take “Lady Sybil’s Seafood Newberg.” Syb of course could not cook: One episode of Downton revolved around her scandalous decision to go downstairs and learn how to prepare some food. What then is the tie between her and the seafood? It is “the zestiest of Downton Abbey’s offerings… just like Lady Sybil’s own personality!”

Sybil’s poached salmon has no nexus with her whatsoever: the Granthams ate it during an argument, so “[t]he spices used in this dish, while adding heat, are nothing compared to the hot tempers seething that night!” What spice? It consists solely of “1 pinch cayenne pepper,” hardly enough to amount to an incendiary element.

Elsewhere “the Countess of Grantham--and all the daughters of Downton--are just as layered as… ”, yes, Veal Orloff and “while,” like the spinach salad, “the girls themselves possess hints of sharpness, underneath it all they are well-meaning and quite delightful.” Maybe so, but the Editor has encountered any number of spinach salads that display a bad intent. It is dreadful to contemplate the contents of the same author’s other leap aboard a bandwagon, The Unofficial Hunger Games Cookbook.

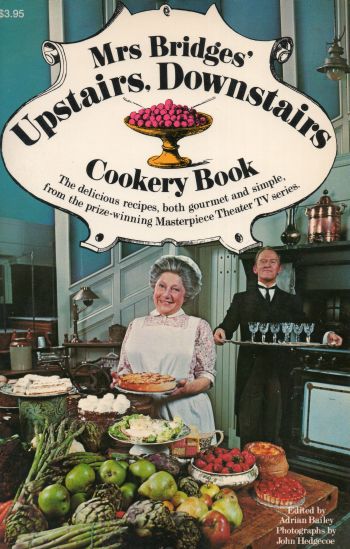

Better to buy any number of other books covering the food of prewar British Big Houses (for there is plenty of dining at the Scottish estate of Earl Grantham’s cousin Shrimpy too) including Arabella Boxer’s Book of English Food and Your Granny’s Cook Book by Sheila Hutchins, to name but two. And if you want to stage your own Downton dinner, choose another tie-in, from Upstairs Downstairs. Mrs. Bridges’ Upstairs Downstairs Cookery Book was compiled by the estimable Adrian Bailey in 1975. A good choice for the project, Bailey had been editor of Harpers & Queen and knew more than a little about British food. He had written the excellent Cooking of the British Isles for the ‘Time-Life Foods of the World’ series back in 1969.

Edwardian recipes, including recipes for Chicken Asquith and Lamb Chops Portmanteau, appear in the practical.