An Appreciation of Hugh Acheson

1. Undiluted idiocy.

On Friday 24 April the governor of Georgia, Brian Kemp, issued a proclamation urging a number of businesses including gyms, restaurants and, bizarrely, bowling alleys, massage parlors, tattoo parlors, hair salons, massage centers, nail spas and waxing studios to reopen. That despite a steadily increasing number of coronavirus cases, hospitalizations and deaths in the state. Georgia still has met none of the tepid federal prerequisites for reopening any business statewide but no matter.

Kemp chose not to burden any mayor of a major city in Georgia with prior notice of his proclamation. They all oppose it with vehemence for the obvious reason. The virus hits cities hardest. Dogma, however, will demand its alternative facts.

Remarkably, and remarkable for the profound ignorance, lack of intellectual curiosity, abrogation of responsibility and callous unconcern it betrays, Kemp confessed on 2 April that he had not known the virus may be asymptomatic even though by then the Center for Disease Control-- located in Atlanta --had published that medical fact precisely three months earlier on 2 January. Since then the media across all platforms and the entire nonderanged ideological spectrum has reported the fact repeatedly.

Hugh Acheson (photo by Martha Williams for Atlanta Magazine)

2. A principled counterattack from a prominent and pathbreaking chef.

The same day the governor issued his proclamation The Washington Post published an editorial by Hugh Acheson, an Ottawa native who owns three restaurants in Georgia. He will have none of Kemp’s proclamation:

“I, as a chef and restauranteur, refuse to have the people I employ and work with used as sacrificial lambs for an economic uptick that is far from guaranteed anyway.”

And, he might have added, solely in an attempt to enable the reelection as president of an odious con artist with no regard for the lives of his constituents, who promptly threw Kemp under the bus anyway when public opinion turned against the reckless sycophant.

This magazine has admired Acheson since the 2011 appearance of his first cookbook, A New Turn in the South. The title is apt enough because although the book bears an unmistakable southern cast. “[W]hile my Southern friends and family had their mothers’ recipes to preserve and pass down,” as a Canadian, he explains,

“ ….I had a relatively blank slate to interpret Southern food my way: to take a fresh approach and turn the traditions on their heads a bit.” ( New Turn 16)

Acheson is the culinary equivalent of Mies, a worshipper of elegant simplicity. “Simple,” he warns, “can be difficult, so we have to pay attention.” On the pitfalls of salting, for example:

“ ….if you use too much you can’t fix it and have to start again. Swear in a foreign language and start over.” ( New Turn 17)

As the advice indicates, Acheson is both unpretentious and meticulous. He likes Pabst Blue Ribbon, but from “the bottles as opposed to cans.” ( New Turn 64)

3. Foundations.

Acheson trained at a number of prestigious American restaurants, maintains that “ ….French technique …forms the foundational blocks of everything I cook…. ” and also credits Greek, Spanish and North African influences but nothing British for his fresh approach. ( New Turn 14, 17) His knowledge of culinary history, however, is not as good as his cooking skill.

After all, even Karen Hess, no culinary Anglophile, understands that the American south built its culinary canon on a British base. While she does identify a number of other significant influences, Hess concedes that “the overwhelming basic influence in the various Southern cuisines was English.” (Hess 80)

How does that influence manifest itself in Acheson’s work? For a start, at the end of his introduction to A New Turn in the South : “Now, let’s make some collards.” ( New Turn 17)

His instruction is appropriate. Collards are an icon of the southern kitchen and perhaps the icon of the African American kitchen in the south. The collard also, it transpires, is an old crop that the English introduced to North America.

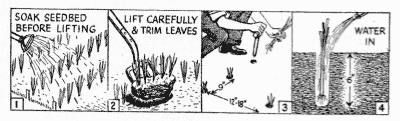

Edward Davis and John Morgan ask the readers of Collards: A Southern Tradition from Seed to Table , to “[i]magine this:”

“In the early 1700s, in a village somewhere in England, a woman slipped a spoonful of collard seed into a cloth bag. Not long afterward she left her home and boarded a ship for Charleston, in the American colonies. After she arrived, she began to plant her garden.” ( Collards ix)

The enterprising colonist understood the unusually efficient and nutritious qualities of her colewort, which collards then were called. As Davis and Morgan explain, by the time she was planting in South Carolina the English had begun to pronounce the leaf collard “and over the next hundred years the spelling would gradually follow suit.” ( Collards x)

Collards would take the south by horticultural storm. In contrast, the collard faded from favor on the eastern rim of the Atlantic.

“Although by the 1830s people who stayed in England had largely forgotten the collard and adopted in [its] place the heading form--cabbage--… in the Southern colonies the collard had become a standard feature of the fall and winter landscape as well as diet…. ” ( Collards x)

The collard, originally an authentic English staple, lost its initial culinary identity to become unmistakably southern. So much for the universality of a French foundation.

Collards of course could be outliers to A New Turn in the South but in fact British technique and influences lurk within its recipes. Acheson notes “the classic flavor affinity of mushrooms and sherry,” the pair a British staple; his chanterelles on toast, a bedrock British dish, gets a jolt of the fortified wine and it flavors a mushroom soup. ( New turn 101) He likes Sherry, or rather Sherry vinegar, with the Brussels sprouts named for Prince Albert and beloved throughout Victoriana.

Acheson enhances the pungency of cabbage with caraway, a staple of the British larder until supplies evaporated with the First World War.

His lamb shanks embellish the more austere British palette, braised with the traditional carrots, celery, leeks, the symbol of Wales, turnips, fennel--one of the oldest vegetables cultivated there--and flavored with mint, but also boosted by tomato and cumin. A very busy dish and a good one.

Acheson likes leeks and considers them underutilized in the American kitchen, and he is right. He does not say so, but his recipe for potatoes mashed with them describes champ, which amounts to the national dish of Northern Ireland.

“A pilau,” as he says, “is a pilaf is a pirloo.” ( New Turn 237) By any name the British brought the rice based dish, something that evolved via the Raj, with them to North America too.

On the sweet side his crème brulee is more British than the British; he flavors it with tea. The dish originated in England and appears in print as burnt cream long before it acquired a French name. “A clafoutis is,” as he says, “a classic French dessert.” ( New Turn 285) A clafoutis also is a batter pudding and it too appears in England at an early date. The British historically have done a lot more with batters both savory and sweet than France and continue to do so. The variations on toad in the hole alone may outnumber the French repertoire.

Those are some examples: We could go on.

4. Science and social distancing instead of stupidity.

Acheson’s brave defiance of a red state edict that, as he writes and the governor knows, “dismisses science in favor of throwing the economically desperate to the front line of the fight against the novel coronavirus pandemic” only increases our regard for him. He could have kept his restaurants closed without making a stir but instead has chosen to invite the wrath of dangerous and often armed rightwing extremists who will leap at any Trumpish inanity to punish, harass, even harm anyone he, and therefore they, consider apostate.

The editorial is anything but anodyne. Acheson is impressively impolitic:

“I hope the governor will be getting a tasteful lower-back tattoo tat says ‘These Veins Bleed Red’ will enjoying a pedicure in a fine Spring Rhubarb shade; alter all, he has a phalanx of people in personal protective equipment willing to ensure his safety, something that the rest of the citizenry has little access to.”

Unlike the governor, Acheson has carefully considered the consequences of reopening a business for his people:

“A line cook probably has roommates, may not have been great at social distancing, probably will take mass transit to work, and then be sent to the grocery store to prepare for food service. They will have hundreds of contact points to put them in a dangerous position, and then countless ways to spread the virus if they get it.” (“No, Governor Kemp”)

5. Communitarian contribution and sacrifice.

It is not as if Acheson has had nothing to lose from the lockdown. At the time the editorial appeared his revenues had suffered a decline of some 95%. He has, however, had a lot to give.

His communitarian convictions are not new. Among the earliest exponents of the locavore movement, he insists that his advocacy “has nothing to do with a political stance and everything to do with a community stance.” He is, he explained back in 2011, “not a fanatic, just a believer.” ( New Turn 136)

Soon after the plague struck Georgia Achreson’s restaurants, with support from a number of nonprofits and a law firm, began to serve the people fighting on the front lines and those suffering the most. (“No, Governor Kemp;” Shalhoup)

“Our mission, Acheson also insists with some credibility, “is entirely apolitical.” The fanatics these days are the Trumpies who put politics before the polity, who disregard epidemiology in favor of expedience. His food goes out to emergency medical teams, hospitals, clinics and other medical centers, underprivileged parts of Athens and Atlanta, homeless shelters, small towns and what he inclusively calls ‘ministries.’ (“No, Governor Kemp”)

Consider the courses of Brian Kemp and Hugh Acheson. To paraphrase Moll Flanders, whose would you choose?

Sources:

Hugh Acheson, A New Turn in the South (New York 2011)

“No, Governor Kemp, I won’t open my Georgia restaurants on Monday,” The Washington Post (24 April 2020)

Karen Hess, “Historical Notes” to Abby Fisher, What Mrs. Fisher Knows About old Southern Cooking (first publ. San Francisco 1881; facsimile, Bedford MA 1995)

Mara Shalhoup, “Chef Hugh Acheson: ‘My real worry is for all the people that I promised to provide for and can’t,” Atlanta Magazine (29 March 2020) (accessed 7 April 2020)