Double bonus occasional miscellany: The cult of orange, Fly Girls & a Smart Aleck.

1. No royalty please, we’re cooks.

This cult does not worship the memory of William III or the modest Dutch royal family as we know it but rather the fruit. Citrus always is in season and, so far in this time of plague, has remained in ready supply.

Conscientious readers will have observed that this website veers to the savory over the sweet, and the orange works equally well in either category. It is, however, underutilized on the savory side. That was not always the case, at least not in terms of British foodways, and if a strange artifact is any indication, was not the case in the nineteenth century United States either.

The artifact dates to Philadelphia during 1909. It is 365 Orange Recipes; An Orange Recipe for Every Day in the Year by a Mrs. J. L. Lane. Mrs. Lane and her book are extremely obscure. Although a print on demand facsimile is available, otherwise 365 Recipes appears to have sunk from historical consciousness without much trace.

2. An unanticipated Record.

At the time of publication, the Experimental Station Record of the United States Department of Agriculture logged its appearance with a capsule description but no more. No other publication appeared to notice.

The Record itself is a curious compilation with a number of obscure and bizarre entries. A lot of them; the Record runs to nine hundred pages divided into eight separate numbers. Its index of subjects requires eighty one pages, the index of names another 18.

“New legislation and legislative enactments regarding fraud and adulteration” appears noteworthy enough, along with the note on “[a]gricultural aspects of the pellagra problem in the United States.” (Record 169, 164)

Consider, however, the Record entries describing analyses of kafir beer or the “Report of the civil veterinary department, Eastern Bengal and Assam, for the year 1908-09.” Perhaps the Department of Agriculture anticipated the American acquisition of a British imperial possession. Perhaps the department also cast its covetous eye to the south with its entry for “the cost of living in British Guiana.” (Record 851, 372)

Closer to home and perhaps at home in the United States (the Record does not say), a report on the “physiological effects of breathing deep” might, possibly, have some bearing on the public health although it remains difficult to determine how the topic involves agriculture.

While advice about “[g]arden accessories and mushroom growing from the Colorado station” would appear to provide welcome advice about fungiculture, the description involves a degree of misdirection because in fact the report consists of “popular directions for the preparation and use of cold frames and hotbeds [not ‘hot beds’ as with cold frames], sterilizing the seed bed for tomatoes and other plants” and, incidentally, “mushroom growing.” (Record 640)

Hats off to those happy pranksters at the Department of Agriculture back in the day: Best of all may be the article on “Goat Raising in Norway, 1660-1814.” The department may have treated its readers to a translation of the title because it appears in a journal called “Tidiskir. Norske. Landbr. Someone at the department must have read it based on the informative synopsis from the Record: “A historical sketch.” (Record 774)

3. A rediscovery of sorts.

365 Recipes lay for the most part neglected for over a century until David Shields addressed it, or rather one of its recipes, in Southern Provisions during 2015. His mention is brief but links the recipe for “Kentucky Orange Pie” to a pair of other sources. The earlier one, Sarah Rutledge’s Carolina Housewife, is an American classic. It appeared in 1847; by then the South Carolina lowcountry had developed its own distinctive outgrowth of the British colonial model. Rutledge calls it “orange pie” but in fact it also includes apples, a counterintuitive combination.

“While folk wisdom suggests,” as Shields explains,

“that apples and oranges are fruits so distinct as to have nothing in common, their marriage in a bath of sugar can be a splendid melding of their different qualities.”

He maintains in awkward prose that the splendid pie represents “the first American instance of a dessert that would become a fixture in nineteenth century American cookbooks.” (Shields 333) The argument would appear to be that the ‘pie’ was the first distinctively American dessert to enjoy wide publication, if true then signal evidence of the longlasting, predominant British influence on the American kitchen.

Not so fast; while the British influence was predominant, the Rutledge dessert, not so much a pie as hollowed oranges filled with their mashed pulp and applesauce baked under a protective pastry lid much like the cover of a casserole that English cooks habitually discarded, was not the first American recipe to find a wide audience beyond its original source.

4. The New England precedent.

During 1796, Amelia Simmons, perhaps a pseudonym, published the first American cookbook in Connecticut, in a region beyond the interest or, apparently, knowledge of Shields. Her American Cookery includes three distinct variations on “A Nice Indian Pudding,” the first appearance in print of “this distinctively American type of pudding,” a New England creation and classic based on cornmeal, a grain neither indigenous to Britain nor particularly liked there until at least the second half of the twentieth century. (Northern Hospitality 332)

American Cookery went through multiple print runs for decades, was pirated wholesale under false authorships and raided by the usual plagiarists for particular recipes--including Indian pudding. “Simmons’s basic formula was followed by many later writers.” Among them; “Mrs. Horace Mann” (Boston, 1857), “Mrs. S. G. Knight” (Boston, 1864), Maria Parloa (New York, 1882), “Mrs. S. W. McLaughlin of North Dakota (Chicago, 1893) and many others. “In the heyday of the Indian pudding, as Keith Stavely and Kathleen Fitzgerald note in their superb Northern Hospitality, the Parloa “recipe had legs, as the journalists say.” (Northern hospitality 345-46, 347)

American Cookery went wherever New Englanders went, through Upstate New York, west to the Ohio country, into the Northwest Territory and all the way up to the Pacific Northwest, so its influence likely has been greater than that of The Kentucky Housewife notwithstanding a widespread tendency to denigrate New England foodways outside the region. (see, e.g., United Tastes passim)

5. A credibility gap.

Southern Provisions unfortunately suffers three additional lapses on the subject of the orange pie alone. Shields claims that 365 Recipes pairs apple and orange in three other recipes but missed a fourth, for “Apple and Orange Tart.” And while he notes that the pie recipe from Mrs. Lane is simpler than its predecessor, he fails to note that unlike the earlier dish it recognizably is a true pie and bears nearly no resemblance to the version from The Kentucky Housewife, casting doubt on the claim that the Rutledge recipe was a template for Mrs. Lane and other writers.

Shields also maintains that “a version of Rutledge’s recipe alternating sliced oranges and apples became a ‘much esteemed delicacy’ in the country districts of England over the century.” (Shields 334)

At the outset the version in question is, in common with the Lane recipe, utterly unlike the Rutledge template. In addition, Shields cites but a throwaway line from a single source for so sweeping a statement. It is a New York publication from 1901, not 1941 as Shields states, called How to Make Money in a Country Hotel. He fails to note that the author, Charles Martyn, wrote it under the pseudonym J. H. Elliott Lane.

The eccentric not to say bizarre Lane was no scholar but was both prolific and scattershot in his choice of subjects, among them The British Cavalry Sword Since 1600, Foods and Culinary Utensils of the Ancients, the genealogy of an obscure figure from the American Revolution, Martyn’s Menu Dictionary, a manual for wine stewards, a book on hotel management more generally and “Fables” of the Hotel Profession combined under the contiguous title of and Poems of “Good-Cheer” on a different subject by a different author. (Quotation marks in original) Martyn calls his first fable “The Smart Bellboy.” It is typical of his work:

“Said a bell boy to himself, ‘There is nothing in the business nowadays unless you are pretty Cute. I’ll show ‘em what I can do in that line.

First off, he decided that he would not run bells to Stiffs who didn’t know enough to part with their Coin. So he chasseyed around until he found out Who was Who, and then he Fixed the bell captain

This gave him time to think up a scheme to Beat the bar, and his Roll commenced to grow with Great Rapidity.

His next idea was a partnership with some Fly girls and a consequent closer acquaintance with sociable drummers. Soon he was so shrewd you couldn’t touch his idea of himself with a flag pole.”

Cute bell hops…shooting craps?

When Martyn was describing the Cute bellhop, ‘fly girl’ was slang for prostitute and ‘drummer’ variously for gambler, john, thief or traveling salesman, so the intrepid if tragic egotist was running with a fast crowd.

“He became quite Well Known. He did a little Private Detective work for jealous men and women. In fact he stood in with a lot of Good Things.

But One Sad Day he spied on a man who was very Harsh and Muscular, and the man Wolloped him and took him down to the Manager.

The Smart Aleck lost his position. His reputation is that he is a dangerous boy to have, and he has secured no decent job since.

Moral: Don’t try to be too slick.” (“Fables” 7; capitalization and spelling in original)

Martyn might have done well to take his own advice.

Most of How to Make Money describes some rather self-evident advice along with a few sharp practices. Its “Supplement” consists for the most part of putative recipes allegedly given Martyn by accomplished hotel chefs and other characters, “The Congressman,” “Theodore” and “The Wig” among them. (quotation marks also in original)

The recipe sequences can be sparse. “Broiled Turkey a la Gourmandise” instructs the cook to… broil some turkey and surround it with fried tomatoes and mushrooms.

Beneath the caption “The Delicious Muskrat,” Martyn maintains that its “flesh is pronounced delicious by epicures” and “may be prepared in almost any way.” (How to Make Money 145)

The entire entry for “Gingerbread:”

“Stale cake finely crumbed and added to the dough makes an excellent gingerbread.” (How to Make Money 150)

So to the orange pie Martyn associates with English country innkeepers. The claim would appear on a par with the recommendation of muskrat and ‘recipe’ for gingerbread. Nothing supports it.

While some British (and American) apple pie recipes before and during the period in question contain a little orange juice or zest and occasionally marmalade, we have unearthed only a single reliable source describing something like a pie filled with apple slices and orange sections. Otherwise the the combination does not appear in the comprehensive compilations, not in Mrs. Beeton nor Elizabeth Craig or Glyn Hughes, not in the scholarship of Elisabeth Ayrton, Elizabeth David, J. C. Drummond and Anne Wilbraham, Theodora FitzGibbon, Jane Grigson, Dorothy Hartley or many others. And not from the internet.

The sole example of an orange and apple pastry is not quite a pie but rather a ‘flan tart’ that Lizzie Boyd describes in her indispensable but overlooked and underrated “guide to culinary practice in the British Isles. British Cookery first appeared, in the United Kingdom, during 1976 and in an unexpected turn a small publisher in Woodstock, New York, issued an American edition three years later. The formidable survey has languished out of print ever since then.

The recipe from How to Make Money is typically cursory and a bit vague but nonetheless among his best:

“Lay in your dish some oranges (peeled with all white and pips removed, and cut in slices). Put over some sliced, peeled and cored apples. Repeat the layer of oranges, squeeze in a little lemon juice, sprinkle with castor sugar according to sweetness of the fruit, and add sufficient water to moisten well. Cover with a thin crust and bake light brown, sprinkling on a little pounded sugar just before taking out.” (Martyn 148)

In contrast the tart from British Cookery turns the Martyn pie upside down. The Boyd formula begins with the cook’s choice of a “savoury, sweet or rich shortcrust pastry” (instruction about each variation appears elsewhere in the book). Then Boyd instructs her reader to “arrange the fruits in layers, dusting” each of them with a spiced binder made from “sugar, cinnamon and flour.” The flan, “essentially similar” to traditional English ‘plate tarts’ is finished by painting it with a layer of molten marmalade. (Boyd 373)

Other than the use of apple and orange the considerably more sophisticated Boyd version bears no resemblance to Martyn’s, and although she considers the recipe “suitable” for both “commercial” and “domestic” kitchens Boyd does not associate it with a country hotel. (Boyd 3, 373)

In any event Shields neither cites Boyd nor includes her compilation among within the extensive bibliography embedded in his endnotes. So it appears he has drawn an unwarranted conclusion about the dish in question from a single unreliable source. All this casts some doubt on the reliability of Southern Provisions writ large.

6. Something of a stretch…

Mrs. Lane evidently encountered some difficulty assembling so many recipes. Many of them are slight (shredded wheat with orange sections for 9 September) or similar (jelly after jelly) or both. Some of the 365 recipes also anticipate the cloying concoctions of midcentury America; things like the extensive reliance on ornate molds and gelatin more generally, or cold fruits drowned in mayonnaise.

Other recipes look back to the less salubrious side of the vast Victorian culinary spectrum. Mrs. Lane’s boiled ham (7 July), for instance, probably does not really like its sweet cherry sauce.

4… but wait, there’s more!

There is, however, lots to like in 365 Recipes. Some of the recipes display a distinctive ancestry. A number of national influences are apparent, among them British. Scotland as expected--lots of marmalade--gets good representation. England appears throughout the year, in particular but by no means only through its traditional desserts and drinks. Even a divided Ireland has its day, not in the case of 365 Recipes St. Patrick’s but in the form of Ormond Cake; Partition split the territory of the Ormond estate between republic and crown in 1914.

Alas, nothing of Wales, which is justly famed for its unique marsh fed lamb tinged with a subtle tang of salt.

7. Strange bedfellows?

Among the most intriguing but lost traditional treatments from Mrs. Lane is her marriage of orange to lamb. 365 Recipes includes three of them, for chops, heart and breast of lamb. All of them include what amounts to an orange sauce.

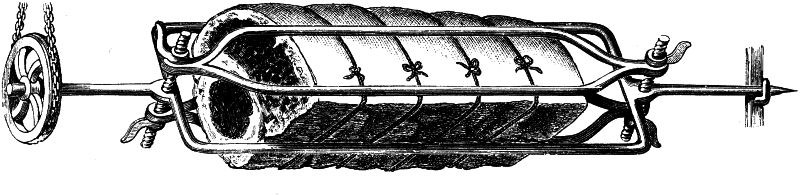

The recipe for breast of lamb, however, goes further by stuffing the meat using a distinctively early modern English technique. In The Accomplish’t Cook that first appeared in 1660, Robert May roasts a chine of mutton larded with orange peel.

Mrs. Lane relies for her stuffed breast on a forcemeat made from a chopped, peeled and pulped orange along with half a cup of blanched almonds and four times that amount of fine breadcrumbs. The breast is rolled, tied then basted “with 1 cupful of hot water in which 1 sliced orange is steeping” for half its baking time of an hour for a three pound cut. (365 Recipes 72)

Ivan Day, culinary historian and historicist cook, refers to rather than actually updates the May recipe notwithstanding his claim to the contrary. His version, while more of a challenge than anything analogous from 365 Recipes, is simpler than its seventeenth century forebear, a version that is not only literally but also figuratively Baroque.

May suggests spiking his orange infused lamb with cloves or any number of herbs but not both, and serves it with any of sixteen sauces. For the first, May asks his reader to

“make sauce with mutton-gravy, and nutmeg, boil it up with a little claret and the juyce of an orange, and rub the dish you put it in with a clove of garlick.” (May 139)

Day does laboriously lace his lamb with long ribbons of peel using a larding needle, which requires some practice to master. A less confident cook could simply slash the meat and shove shorter sections of peel into the slits.

A stickler (or sticker) like Day will roast the lamb on a spit. He owns a number of eighteenth century implements including various spits and jacks but no dogs, which were bred for the purpose of turning spits on a treadmill by subjecting them to the carrot technique, in their case a morsel of meat dangling just beyond reach. His favored machine requires only winding a contraption of pulleys, belts and gears. (Russell)

As Day notes, the traditional technique “produces the most wonderful succulent meat but you can also use this method cooking the meat in the oven.” (Ellis) The dish itself and baking it in an oven are recommended, and so is the simpler stuffed shoulder from Mrs. Lane.

Recipes that pair lamb with orange appear in the practical along with a number of others incorporating oranges, their juice or zest.

Sources:

Elisabeth Ayrton, The Cookery of England (London 1974)

English Provincial Cooking (London 1980)

Good Simple Cookery (London 1984)

Elisabeth Ayrton & Theodora FitzGibbon, Traditional British Cooking: A Regional Guide in Colour (London 1985)

Isabella Beeton, Beeton’s Book of Household Management (London 1861; facsimile London 1982)

Lizzie Boyd, British Cookery: A complete guide to culinary practice in the British Isles (Woodstock NY 1979)

Elizabeth Craig, Cooking with Elizabeth Craig (London 1932)

Elizabeth David, Spices, Salt and Aromatics in the English Kitchen (London 1970)

Hattie Ellis, “Ivan Day recipes: Orange-larded leg of lamb or mutton and grand salad,” The Telegraph (London) (1 January 2009)

Jane Grigson, British Cookery (New York 1985)

English Food (London 1974)

Jane Grigson’s Fruit Book (London 1982)

Dorothy Hartley, Food in England (London 1954)

Glyn Hughes, www.http://foodsofengland.co.uk (accessed 30 April 2020)

The Lost Foods of England (Winster, Derbyshire 2017)

J. L. Lane, 365 Orange Recipes: An Orange Recipe for Every Day in the Year (Philadelphia 1909)

Charles Martyn, How to Make Money in a Country Hotel (New York 1901)

Laura Mason & Catherine Brown, Traditional Foods of Britain: An Inventory (Totnes, Devon 1999)

Robert May, The Accomplish’t Cook (London 1660; facsimile Totnes, Devon 2012)

Sarah Rutledge, the Carolina Housewife (Charleston 1847; facsimile Columbia SC 1999)

Polly Russell, “The history cook: Food of Christmas Past,” Financial Times (28 November 2014)

David Shields, Southern Provisions: The Creation & Revival of a Cuisine (Chicago 2015)

Keith Stavely & Kathleen Fitzgerald, Northern Hospitality: Cooking by the Book in New England (Amherst MA 2011)

United Tastes: The Making of the First American Cookbook (Amherst MA 2017)