Occasional Miscellany: A note on dining, drinking & whoring at college in early New England

At the outset of the twentieth century Mary Caroline Crawford wrote a decidedly old fashioned book called Social Life in Old New England. Among the facets of society she described is student life at the venerable universities and colleges in the region, and among the facets of college life, the food.

Crawford has nothing to say about dining at Dartmouth, Williams or Yale, presumably because she found no source for them, but does go into some detail about two of their contemporary institutions. “The student’s life was hard” at Harvard as late as the outset of the nineteenth century, and the hardship then extended to the variety of food, or lack of it, foisted on its inmates.

2. A penitentiary regimen.

A weekday at Harvard began at six with morning prayer “in a bitterly cold chapel” followed by two “recitations,” or class periods. Only then were the students served breakfast,

“which in the college commons consisted solely of coffee, hot rolls and butter, except when the members of a mess had succeeded in pinning to the nether surface of the table, by a two-pronged fork, some slices of meat from the previous day’s dinner.” (Crawford 71)

“Dinner,” Crawford continues,

“was at half past twelve,--a meal not deficient in quantity but by no means appetizing to those who had come from neat homes and well-ordered tables.”

Crawford provides no details about the unappetizing dinner, but it must have included the meat, if only on occasion, that hungry students stole and stowed on the underside of their breakfast tables.

Watercolor study by a starving artist – student.

Notwithstanding the first two austere sittings, the lowlight of the dining day was “the evening meal, plain as the breakfast, with tea instead of coffee and cold bread of the consistency of wool, for the hot rolls.” (Crawford 72)

All this may sound somewhat conclusory but other evidence, including an epic episode in the history of Harvard, indicates that Crawford did hit the culinary mark. In 1728, for example, Harvard punished nearly two dozen students for stealing and roasting geese. (Moore 652)

Throughout the eighteenth century Harvard students staged a number of “routs,” or riots. Some resulted merely from high spirits, others from conditions the students found unacceptable. A number of the protests “were prompted,” as Kathryn Mcdaniel Moore explains, “by bad food.”

The famous Bad Butter Rebellion of 1766

“began as a complaint against bad food in the commons and escalated to a highly charged debate between the students, headed by the governor’s son, and the board of overseers, headed by the governor, over the obligation to obey an unjust sovereign.” (Moore 653)

The diet must have been dire indeed to drive a protest that would engulf the great debate of the age, especially in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, beset as it was by an unbearable tension. That tension seeped beyond the conflict between the North American colonies and the metropolitan power back in London. Puritan doctrine, and the Harvard administration itself, demanded that

“persons in superior positions to oneself were to be reverenced and obeyed. Not only was the catechism of the fifth commandment applicable, but the college laws and customs also specifically stated this policy.” (Moore 650)

The lust for liberty that had long characterized the broader culture of New England, however, would have none of that, and by the middle of the eighteenth century neither would a vocal and active segment of the Harvard student body.

Early campus activists, starting with the bad food.

3. Fighting the power.

Harvard required attendance at chapel for a second session each day and forbade its students to leave campus except, occasionally and only with permission, on Saturday. These requirements proved unpopular. Between 1750 and 1760 Harvard punished any number of students for “misconduct in chapel, profaning the Sabbath and other impieties.” (Moore 652)

Notwithstanding these conditions, apparently modelled on the regimen at Newgate Prison or a nunnery, and the recurrent riots, Harvard men, for all of them then were men, appeared happy enough.

“After tea,” according to Crawford, “the dormitories rang with song and merriment,” if only for a time each day. The “study bell, at eight in winter, at nine in summer, sounded the curfew for fun and frolic, proclaiming dead silence throughout the college premises.” (Crawford 72) Austerity indeed.

In fact the merriment extended a good way beyond song and the hour or so after dinner: as the record indicates, Harvard students were a lot more rebellious and subversive than Crawford infers. “Drunkenness was rampant and other crimes fed upon it, including fighting, lying, swearing, and card playing.” Harvard sent a number of students from the classes of 1766 and 1767 home with “the itch” they acquired from “associating with, countenancing, encouraging one or more lewd women kept by the students.” (Moore 652) Plus ca change….

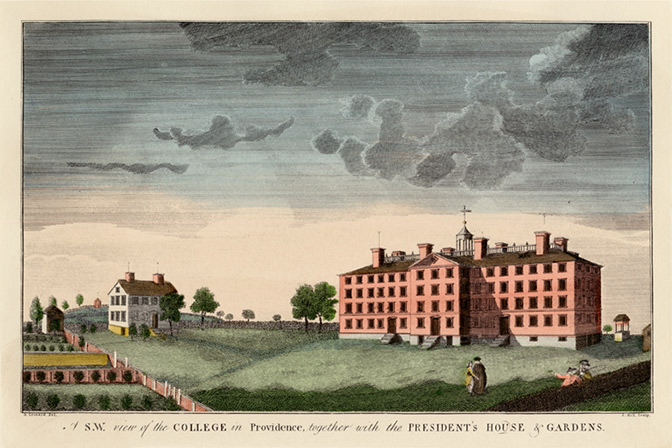

4. An ivy outlier, even then.

A contrast to conditions at Harvard prevailed some fifty-five miles southwest of Cambridge. While it is doubtful the students behaved much different from their counterparts to the north, religious strictures were not so strict. Brown, or Rhode Island College as it was until 1804, had been established by Baptists. From the outset, however, they sought to ensure it would remain unaffiliated with any church. The radical departure in fact conformed to the nonconforming, not to say heretical and scandalous, society Roger Williams founded in Rhode Island.

“Picturesque customs” characterized Brown from the beginning according to Crawford, “and a very generous attitude towards ‘town’ as well as ‘gown.’” (Crawford 87)

Brown was unique in its liberality. “College rules during the eighteenth century,” Crawford explains, “are all a good deal alike, but Rhode Island College showed its individuality” through, for example, the “Laws and Customs of Rhode Island College, 1774.” (Crawford 89-90)

Among other things, Crawford cites a provision exempting students from the requirement to attend church service “on the First Day of the week steadily” provided they “regularly and statedly keep the seventh day as the Sabbath.” Although Harvard required students to attend services fourteen times a week, at what became Brown they needed not endure church at all.

A provision also exempted “young gentlemen of the Hebrew nation,” who were then prohibited from attending Harvard or any of the other New England colleges, from considering the New Testament as, in Crawford’s words, “divine authority.” Students were forbidden hats “within the College walls” except for “those who steadily attend the Friends’ Meeting” at a time when Quakers also were disqualified from attending college elsewhere in New England.

More generally, undergraduates were “only required to abstain from secular concerns which would interrupt their fellow students.” (Crawford 90)

Crawford provides more detail about the food served at Brown than about food at Harvard because she found documentation from 1773 for regulation of the commons at the Providence institution. Nine years after its foundation, Brown issued strict instructions to the steward responsible for feeding its students.

In general, all provisions “shall be good, genuine and unadulterated. The meals are to be provided at a stated,” but not prescribed, “time, and the cookery shall be well and neatly executed.”

It would not be anachronistic to observe that a broad diversity, in the eighteenth century context, extended from the student body to the table. In particular, meals had to be composed of enumerated products cooked in particular ways.

“For Breakfast:

With tea or coffee, white bread with butter, or brown bread, toasted with butter. With chocolate or milk porridge, white bread without butter. With tea coffee and chocolate brown sugar.” (Crawford 90)

The midday meal offered a particular contrast to the “unappetizing” food served at Cambridge.

“For Dinner Every Week:

Two meals of salt beef and pork, with peas, beans, greens, roots, etc., and puddings. For drink, good small beer and cider.

Two meals of fresh meat, roasted, baked, broiled or fried, with proper sauce or vegetables.

One meal of soup and fragments.

One meal of boiled fresh meat with proper sauce and broth.

One meal of salt or fresh fish, with brown bread.” (Crawford 90)

A commons regulation also required a varied menu at suppertime, although the requisite variety was more modest and the discretion of the steward less circumscribed:

“Milk with hasty pudding, rice, samp, white bread, etc. Or milk porridge, tea, coffee or chocolate, as for breakfast.”

More surprising given the monotonous culinary lot of contemporaneous people, whether in western Europe or British North America, the regulations continued:

“The several articles or provisions above mentioned, especially dinners, are to be diversified through the week, as much as may be agreeable; with the addition of puddings, apple pies, dumplings, cheese, etc., to be interspersed through the dinners, as often as may be convenient or suitable.” (Crawford 91)

The food prescribed in the regulations describes the prototypical, if for many less fortunate people aspirational, British diet of the time.

Skeptics will, with some justification, note that the directive dealing with diversification includes a number of qualifications, and may also wonder whether in fact the regulations were enforced.

A few clues hint that they were enforced. For one thing, they required the steward to dine with his charges; if they ate badly, so would he. For another, unless Crawford got her citation wrong (an unfortunate possibility; see the note), the dining regulations remained in effect for some time. Encyclopedia Brunoniana , for instance, cites part of what appear to be the same or similar requirements issued in 1783. And in contrast to conditions at Harvard, at this writing we have found no record of an eighteenth century food riot at Brown.

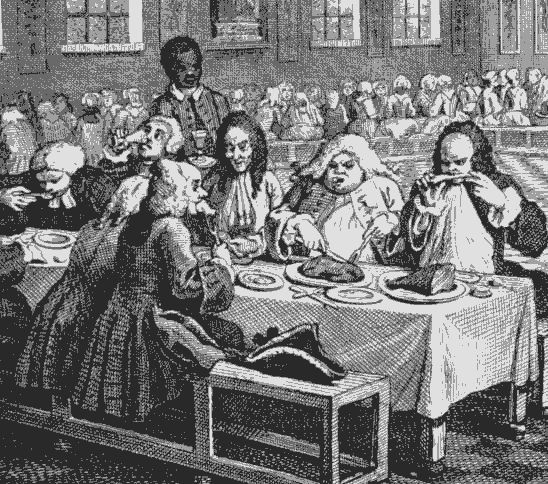

Like this, only with students.

6. Bears in chaos at breakfast.

One student who described culinary conditions in 1820 does not find fault with the food. He describes breakfast tables in the commons “covered with hot rolls, butter, very good coffee & tea & plenty of milk and sugar.” At the peal of a morning bell, he wrote to his father,

“we all issue out and drive down stairs, enough to break our necks, into the dining room…. after that tutor has asked a blessing we set on like bears issuing out of their dens after three months of starvation…. and it is quite amusing to see the immense piles of bread that are demolished in a very few minutes.” (Mitchel 161)

Raucous and ravenous they were, but these students showed no sign of dissatisfaction with the food served in the Brown commons.

None of this, of course, speaks to the quality of education at either institution during the eighteenth century: That serious subject lies beyond the scope of this bagatelle.

Note:

On the concern for the accuracy of Crawford’s narrative; she maintains, for example, that Brown is affiliated with the Baptist church, but while as noted in the text Baptists who founded the place took pains to ensure that their college remained unaffiliated with any church, a tradition that has continued without interruption. Crawford also states that the first class at Rhode Island College graduated a single student while Encyclopedia Brunoniana identifies seven of them.

Sources:

Mary Caroline Crawford, Social Life in Old New England (Boston 1915)

Martha Mitchell, Encyclopedia Brunoniana (Providence 1993)

Kathryn Mcdaniel Moore, “Freedom and Constraint in Eighteenth Century Harvard,” The Journal of Higher Education Vol. 47 No.6 (Nov-Dec 1976) 649-59