Macaroni & cheese: A case study in the condition of culinary historiography during the culture wars.

It should provoke no controversy to assert that macaroni and cheese has become a culinary icon in the United States. For that reason it is a source of fascination to the blogosphere. The sites described are but a few of the many jostling for attention.

Bloggers post not only innumerable recipes but also an array of competing origin stories about the dish. Adherence to one theory or another about the arrival of macaroni and cheese in America depends for the most part on the perspective of the writer within what may be considered without exaggeration a sort of culinary culture war.

The most widespread origin story traces macaroni and cheese to the kitchen of Thomas Jefferson and itself embeds four competing tropes with and without reference to French cuisine. One gives credit to Jefferson himself for introducing the dish to North America.

Jefferson, however, was no cook. One of his slaves was a cook, so his advocates claim he actually introduced macaroni and cheese to the western hemisphere. (see, e.g., McElveen)

An outlier recites a “theory” that “Thomas Jefferson’s wife invented the dish.” (‘Chopbreak’) The only recorded reference to something supposedly resembling macaroni and cheese in connection with Jefferson, however, appears in 1802, two decades after the death of Martha Jefferson, and the first reference to the payment by Jefferson for a pasta machine appears in his ledgers during 1793, the year after her death. (Monticello.org) Nothing indicates that Mrs. Jefferson cooked anything and it is most unlikely that she did: As noted, the Jefferson household had slaves for that.

The subject at hand.

The subject at hand.

Several writers contend that Jefferson’s daughter Mary Randolph, who assumed supervision of Monticello on the death of her mother, created the dish and memorialized it in a cookbook from either 1824 or 1845. (see, e. g., Wright)

Others who consider the origin of the dish African American decline to identify the enslaved cook. Emma Loveland asserts, erroneously, that macaroni and cheese “became a popular dish among Jefferson’s slaves” despite a predictable absence of evidence. At the time macaroni and cheese was a luxury item in the south, limited not only to its elites but also to the holidays they observed, and even the less unenlightened planters would not have lavished it on their slaves. (see, e.g., Woys Weaver 28)

According to Adrian Miller, whose work previously has been admired in these pages, “there are African Americans who believe that we invented macaroni and cheese. So they think it’s something white people stole just like rock and roll.” (Graber et al.)

2. Paths to nowhere.

One writer traces macaroni and cheese, preposterously, to the Talmud; another to ancient Etruscans and another to ‘Italy’ more generally. “There can be no doubt,” Clifford Wright insists, “that its ultimate origins are Italian.” (Wright) Wright presumably places his bet on little more than the presence of pasta in a lone recipe called de lasanis from Liber de Coquina, an anonymous thirteenth century Neapolitan. The recipe in question however merely boils sheets of, logically enough, lasagna before tossing them

“with grated cheese, probably Parmesan. The author suggests using powdered spices and layering the sheets of lasagna, just like today, with the cheese if desired.” (Rhinehart citing Wright)

Just like today perhaps, but only in terms of the sheets themselves. Modern lasagna is ordinarily baked, like macaroni and cheese, while the Neapolitan recipe lacks the essential sauce that defines modern lasagna as well as macaroni and cheese.

As Cynthia Graber observes during an interview with Miller, “if you travel around Italy, you are unlikely to find anything like mac and cheese.” The same was true during the eighteenth century age of the Grand Tour or at any other time. (Graber et al.) The technique is alien to Italian foodways.

Even so, Andrew F. Smith claims in The Oxford Companion to Cheese that whether or not Italians first prepared macaroni and cheese, it “was popularized by Italian immigrants and restauranteurs in the early twentieth century.” (Donnelly 449)

The problem with that assertion is its utter inaccuracy. Italian restaurants do not and did not ordinarily serve macaroni and cheese, while arguing that the dish became popular only at the outset of the twentieth century fails to account for the universality of the recipe in cookbooks published in both Britain and North America throughout the nineteenth century.

The ordinarily reliable Miller also muses, in his case with some inconsistency, on macaroni and cheese as an anomaly in terms of immigrants’ influence:

“And what’s interesting about mac ‘n’ cheese is that it was really popular before we had huge waves of Italian immigrants in this country. Because usually what happens is that an ethnic food becomes popular after the people show up.” (Gebert)

Elsewhere Miller himself, along with many others, notes the appearance of the dish in the antebellum south and its prevalence in colonial New England, an indication that immigrants or their descendants did in fact popularize the dish. It is just that they did not arrive during the big waves of nineteenth century immigration and did not come from Italy.

Wright refers to a thirteenth century appearance in Europe but others ascribe the first print recipe to either France or England during the medieval period through a widely circulated medium, The Forme of Cury.

The attribution to France may be disregarded because its advocate, who may mercifully remain unnamed in these pages, labels the Cury cookbook French when in fact, as the admittedly archaic but nonetheless recognizable words of the title ought to indicate, it was published in England. On examination the recipe in translation resembles a sort of primitive cross between boiled spaetzle and lasagna far removed from anything like macaroni and cheese:

“Macaroni. Take a piece of thin pastry dough and cut it in pieces, place in boiling water and cook. Take grated cheese, melted butter, and arrange in layers like lasagna; serve.” (Hieatt & Butler)

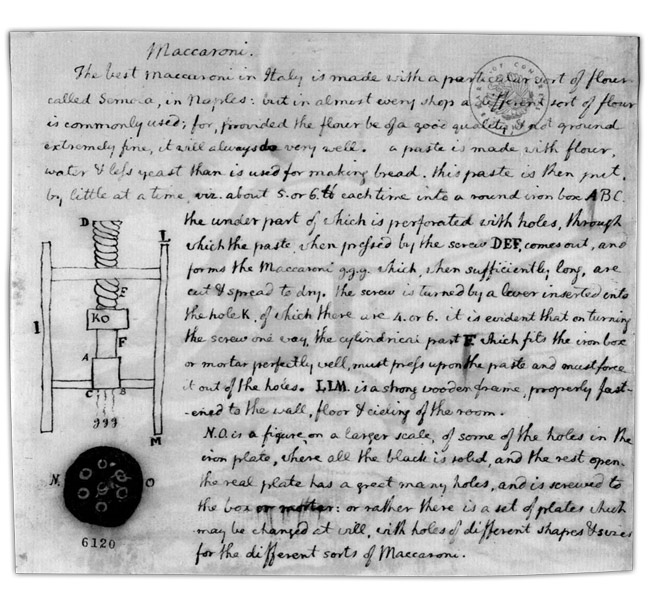

Dating the modern macaroni and cheese assembly to the medieval period is anachronistic for any number of reasons, including technology. What now are considered traditional recipes for macaroni and cheese rely on short, tubular pasta. It had not yet appeared during the middle ages. “The invention of the extruder machine,” like the one bought by the ever curious Jefferson “in the eighteenth century made possible,” as Smith notes, this time on a factual basis, “tubular macaroni shapes….” (Donnelly 449)

Others would ignore the history altogether: At least one blogger believes that “Macaroni and Cheese is largely thought of as a modern dish.” (“fourpoundsflour”)

3. Sins of omission.

The overwhelming mass of all this internet literature on macaroni and cheese shares a signal attribute. Few primary sources are quoted to substantiate any theory and few secondary sources are given credit for their research.

Richard Posner, the conservative economic turned insurgent jurist, discusses this insidious and invidious form of plagiarism. It involves taking credit for the research someone else conducted earlier. The plagiarist may operate in a number of ways.

“For example,” Posner writes,

“a historian might cite a primary source that he had not found or read himself but rather had lifted from a citation in a secondary source that he does not mention, thus appropriating the discovery made by the author of the secondary work.”

Plagiarized research is not just despicable, but dangerous when the thief has not read the cited source and relies on the quotation of it, which may or may not be accurate. It is doubly dangerous when the plagiarist paraphrases the quotation or, worse, a paraphrasing of the primary source by the secondary source without bothering to read or identify the primary source. That practice creates a potential inaccuracy and magnifies the risk that other miscreants will inadvertently continue to distort the facts, engaging in what amounts to a serial game of ‘scholarly’ telephone tag that pushes the argument further and further from the underlying facts.

The plagiarism of research is rampant “because,” as Posner explains,

“unless the primary source is exceedingly obscure or downright inaccessible or the secondary source contains an error in citing the primary source that is carried over into the accused plagiarist’s citation, it is almost impossible to detect.” (Posner 15)

Plagiarism of research creates a particular detriment to its victim because the appropriation erases any record of what can have been a long, laborious search for something lost or new. It is a case “of falsely implying that one did the drudge work (sometimes more than the drudge work) of digging up primary sources.” (Posner 15-16)

Posner had in mind loftier subjects than food, let alone something so quotidian as macaroni and cheese, and while there can be little doubt the transgressions of glib bloggers, many of whom however pass themselves off as serious historians, are misdemeanors in comparison to the felonies of serious scholars. Even so, the bad impact of this kind of plagiarism can be severe because the circulation of misinformation is far more accelerated within the blogosphere than the academy. That may account for the welter of internet misinformation but should not influence serious scholars. Nonetheless it would appear that it does.

Not much scholarship addresses what intuitively ought to be an obscure subject, and with an exception or two the run of it is either incomplete or inaccurate.

4. The African American adoption of a dish.

In Jubilee, her James Beard Award winner, Toni Tipton-Martin quotes Miller, her fellow Beard recipient, to ask a straightforward question:

“How did macaroni and cheese get so black?”

Doubtless it did, and Tipton-Martin supplies a ready answer in the form of “James Hemings, slave and chef to Thomas Jefferson.”

She traces the ancestry of the dish in a straight line from France and Hemings’ “macaroni pie” of 1802 through the “1845” publication of The Virginia House-Wife by Mary Randolph (“a Jefferson relative;” in fact his daughter) to the Kentucky Cook Book: Easy and Simple for Any Cook, by a Colored Woman. The woman was Mrs. W. T. Hayes and her book appeared in 1912. Then Tipton-Martin offers her own, very good, recipe which, she says, draws on a 1947 version described by “Texas caterer Bess Gant.”

Tipton-Martin reiterated the sequence on 4 July in The Guardian, where she also cited a 2014 twitterstorm about collards. For her and others, the publication online by Whole Foods of a recipe for collards with peanuts was an offensive and laughable act of inauthentic appropriation. (“Collard greens”)

Tipton-Martin declines to note in the article, however, that the purported cause of indignation has been disputed as anachronistic in an article from The Atlantic and then discredited as a matter of historical fact by an essay from Petits Propos Culinaires. Collards arrived in North America from England; evidence indicates that African cooks pair them with peanuts. (Friedersdorf; Perkins)

5. Not so fast.

The lineage described is, it transpires, more thin reed than family tree. Jefferson was Francophile and as Tipton-Martin notes, Hemings was steeped in “the sophisticated techniques of French classical cooking.” (Jubilee 177) In her Guardian article she adds that Hemings left a manuscript ‘recipe’ for “Nouilles a maccaroni (macaroni noodles)” which is both true and misleading: A noodle itself is not a dish let alone macaroni and cheese. (“Collard greens”)

Hemings, who recorded a number of recipes, left none of any kind that includes macaroni as an ingredient with or without cheese. A guest who encountered the dinner dish in question at the White House during 1802, however, left a description. Whatever it was sounds nothing like macaroni and cheese as we know it. Nothing resembling macaroni and cheese appears in the French culinary canon any more than it does in the guest’s description of the dish Jefferson served him.

It was a pie of putative Italian origin filled with

“onions or shallots… and what appeared like onions were made of flour and butter, with particularly strong liquor mixed in them.” (“Origin of a Dish”)

The description includes no cheese.

In reality Jefferson and his guests were hardly the only Americans eating macaroni during 1802. A Robert Fresnaye, who “is believed to have been the first manufacturer of Italian pasta in the United States,” issued a broadsheet in Philadelphia during the same year that includes instructions to prepare vermicelli “like a pudding.” “By that,” notes William Woys Warner, “he meant prepared like baked pudding, not so much in texture as in technique.” Unlike the description of the Jefferson dish, Fresnaye’s recipe does include cheese.

Jefferson’s description of a “maccaroni” machine

Jefferson’s description of a “maccaroni” machine

According to Karen Hammonds, his was the “first recorded American recipe for mac and cheese.” (Hammonds) Woys Warner also considers the recipe “as the ancestor of that ubiquitous American dish called ‘macaroni and cheese,’ only Fresnaye’s is infinitely better.” (Woys Warner 28)

Those claims are at best dubious. The Fresnaye recipe looks as if it were lifted from the Forme of Cury except that it is baked and the sheets have been replaced by vermicelli, broken and boiled then tossed with grated cheese and melted butter. (Woys Warner 29)

Randolph’s recipe, which first appeared in 1824, not 1845, also includes cheese but bears no resemblance to a modern dish of macaroni and cheese nor, for that matter, to Hemings’ pie.

It should be no surprise then that Randolph makes no mention of him or his pie.

The Randolph recipe, called merely “Macaroni,” is not so much concise as curt and produces something pretty unpalatable:

“Boil as much macaroni as will fill your dish, in milk and water, till quite tender; then drain it in a sieve, sprinkle a little salt over it, put a layer in your dish, then cheese and butter as in the polenta, and bake it in the same manner.” (Randolph 84)

As for Mrs. Hayes, the recipe that Tipton-Martin reproduces in Jubilee is for a strange sort of deepfried macaroni croquette, not for baked macaroni and cheese, although Mrs. Hayes does lather her croquettes with white sauce laced with cheese and walnuts.

Tipton-Martin does not describe the Gant recipe except to note that it is “rolled up in ham jackets,” not the presentation of the modern dish. (Jubilee 177) Her own recipe does not look like any of its purported antecedents.

6. Misdirection as a narrative device.

The pairing by Tipton-Martin of the question posed by Miller with the answer she provides is misleading in another respect. It turns out that Miller himself is not so sure about either the Hemings connection or the African American origin myth more generally. In an interview conducted a year after his Beard Awarded Soul Food appeared during 2017, Miller recounts how although “Thomas Jefferson,” and by extension Hemings, “gets a lot of credit” for introducing the dish to North America

“that’s really not true. If you look at manuscript cookbooks in the United States [sic] even before Jefferson’s time, people were serving something that was similar to macaroni and cheese in their households. They often called it macaroni pudding.”

Elsewhere Miller is unequivocal:

“I know a lot of older African-Americans who believe that African-Americans invented mac ‘n’ cheese, and that white people are stealing it from us. When it’s clearly the opposite.” (Gebert et al.)

7. Perhaps a Connecticut pudding or Canadian Raffald?

At least some of those households and possibly most of them stood before Jefferson’s time in culturally Anglophile southeastern Connecticut, where references to Miller’s “macaroni pudding” apparently appear during the eighteenth century. The usage of ‘apparently’ is important at this point because neither Miller nor anyone else cites a manuscript source.

In their mammoth L.L.Bean Book of New New England Cookery Judith and Evan Jones claim macaroni and cheese for New England with reference to Connecticut. “Certainly,” they maintain, “the church supper as an institution was responsible for the evolution of macaroni and cheese (which in southeastern Connecticut was known for a while as macaroni pudding).” (Jones 429) The Joneses sound authoritative but provide no citation for that or any other assertion from New New England.

Multiple other sources explicitly trace the first recognizably modern American rendition to southeastern Connecticut during the eighteenth century, also in the guise of ‘macaroni pudding’ but with or without mention of the church supper.

Wright for one refers to the region in his customarily unhelpful way: “In southeastern Connecticut it was known long ago as macaroni pudding.” (Wright) The question he leaves unresolved is how long ago the ‘pudding’ had appeared.

“it is thought that macaroni and cheese was a casserole that had its beginnings in colonial America at a New England church supper. In southeastern Connecticut it was known long ago as macaroni pudding and probably originated from ‘receipts,’ or recipes, passed along from English relatives.” (Holifield)

“Some believe,” according to Korky Vann at the Hartford Courant with an apparent but unpaid debt to the Joneses, “that macaroni and cheese originated as a casserole at a New England church supper. (In southeastern Connecticut, the dish was known as ‘macaroni pudding’).” (Vann)

In an article from the Huntington, West Virginia Herald Dispatch, Derek Coleman discusses and discounts the scenario in which Jefferson introduces the dish. “That may be true,” he allows, “but long before that, and much farther north, in Connecticut, the same type of dish was being served at church suppers as macaroni pudding.” Unfortunately he then recycles the anachronistic narratives involving medieval Europe before jumping to the second half of the nineteenth century and Mrs. Beeton along with the great Alexandre Dumas. (Coleman)

The Joneses’ is the earliest reference to a New England myth of origin among the cited sources and the first to ‘macaroni pudding.’ It is unclear who first identified southeastern Connecticut in particular because some of the articles are undated. All of them are consistent in a respect; none offers anything to substantiate the claim.

8. Go to the source for the answer.

Another indicator points to southern New England but not necessarily Connecticut as the source of macaroni and cheese. If the dish was considered a luxury item in the eighteenth century American south, and it was (Soul Food 130; Holifield; Edgar; “Cheese IQ;” Okwemba), then how can a custom so egalitarian as the church supper account for its creation?

The climate of the colonial south was not conducive to cheesemaking (Soul Food 130), while the three southernmost New England colonies and then New York dominated production in eighteenth century America.

In their pathbreaking study of early Connecticut culture, United Tastes, Keith Stavely and Kathleen Fitzgerald establish that even the elites of Anglophile but fiercely egalitarian Connecticut were dedicated to the ideal of the unpretentious, capitalist smallholder who farmed both subsistence and surplus cash crops.

The description of the dairy farmers who made cheese for export from southern New England is but one example of an industry there that fit the model. Although small dairy farms produced nearly all cheese onsite, the industry was substantial. “A large surplus was produced” in the decades before the Revolution. It found a ready market:

“Cheese from Rhode Island and from the dairy farms of southern Connecticut along the shore of Long Island Sound, was shipped by vessel to the southern colonies and to the West Indies. More than 130,000 pounds of cheese a year entered this trade, quite a respectable total for the period.” (Durand 266, 265)

By 1800 New England merchants were shipping some one million pounds of cheese annually to Caribbean islands alone. (Donnelly 740; “History of Cheese”)

Under these conditions cheese was a commodity, even glut in southern New England, where it either was made at home or available at a cheap price. In contrast, cheese amounted to a luxury import in the south, where macaroni and cheese remained a delicacy limited to the elite and to holidays. (Soul Food 130)

While these factors do provide a basis for belief that macaroni and cheese first appeared in southern New England, none of them alone or in combination could be considered dispositive.

All of which ought to lead us, at least for now, to England and Elizabeth Raffald.

9. An eighteenth century breakthrough of several sorts.

In common with most of the North American colonies and especially New England, Elizabeth Raffald’s Experienced English Housekeeper was a bestseller in eighteenth century Connecticut. It first appeared in 1769, thirty three years before the White House macaroni dinner, and multiple sources maintain that the English Housekeeper includes the first “modern recipe” for macaroni and cheese. (see, e.g., Buttery; Holifield; “Hidden History”)

The recorded recipes combining cheese with macaroni before the version from the English Housekeeper boil the various dishes so if, as appears to be the case, the Raffald recipe was a reasonably recent innovation in eighteenth century Connecticut, calling it a pudding would make sense. As Woys Warner notes, in context the usage refers to a technique, baking, that serves to distinguish the dish from its predecessors.

Far enough afield from Connecticut, one source maintains, if and typically without a source, that the dish has been known as “Raffald” in Canada “for hundreds of years,” which also would push North American familiarity with the dish into the eighteenth century. (“Raffald (Mac & Cheese)”)

And Mrs. Raffald is modern indeed; she laps her macaroni in an English white sauce and tosses it with toasted cheese, although she does not bake it:

“Boil four ounces of macaroni till it be quite tender and lay it on a sieve to drain. Then put it in a tossing pan with about a gill of good cream, a lump of butter rolled in flour, boil it five minutes. Pour it on a plate, lay all over it parmesan cheese toasted. Send it to the table on a water plate, for it soon grows cold.” (Raffald 144)

Her dish has no piecrust, actually sauces the pasta and is neither deepfried nor wrapped in ham.

Corby Kummer, a journalist of considerable integrity, has no doubt how macaroni arrived in North America. He does not refer to Mrs. Raffald but his explanation how English cooks used macaroni describes her recipe:

“Macaroni came to America with the English, who served it baked with cheese and cream…. Macaroni and cheese, then, like many other dishes that the English brought to the Colonies, can be considered an old American dish.” (Kummer)

However good at his craft, Kummer is after all a journalist, not an academic historian, and therefore did not perceive any need to document his sources.

Neil Buttery, “a professional chef dedicated to cooking food from our past” and culinary historian at British Food: A History, concurs with Kummer that “macaroni cheese has its origin firmly planted in Britain. Macaroni cheese emigrated to the US and Canada with the British settlers,” citing the Raffald recipe (although he misspells her name) as his sole authority. (Buttery)

While noting, reasonably enough, that western Europeans and particularly the Swiss also lay claim to macaroni and cheese, Amanda E. Herbert, Assistant Director of the Folger Institute and co-editor at the online Recipes Project, offers her own relatively nuanced and refreshingly substantiated rendition of the Anglospheric lineage of the modern dish:

“Macaroni and cheese appears in Anglo-American cookbooks as early as the fourteenth century--its antecedents include a sort of lasagna-like food called ‘Macrows’ in the 1390 Forme of Cury--and by the long eighteenth century, the cheesy noodles were an established dish, garnering frequent mentions in both print and manuscript.” (Herbert)

Other than the ‘Macrows’ from the Forme of Cury which are not at all macaroni and cheese but as she admits a ‘sort of lasagna,’ the only cited examples of all that frequency, however, are to a manuscript “most likely written and bound between 1765 and 1830” in the collections of the University of Pennsylvania along with a letter written in England during 1770. (Connell; Herbert) Herbert omits any reference to Mrs. Raffald or any other eighteenth century recipe in print.

None of this gets any closer to the Connecticut source of ‘macaroni pudding’ but another indication that the dish arrived in North America from Britain during the eighteenth century does arise from an island nation to the north of the Caribbean. It would appear that as in Canada, a consensus has emerged about the origin of macaroni and cheese in the Bahamas, where it is considered a national dish:

“Bahamian style mac and cheese is steeped in English tradition as it is generally agreed that the original recipe for baked macaroni was brought over by English colonists during the mid to late 1700s and onwards.” (Lee)

10. Straight out of London.

The Virginia House-Wife may not have debuted in 1845, but Eliza Acton’s Modern Cookery, for Private Families did, in London, and became the bestselling British cookbook of its day. Also popular in Anglophone North America, Miss Acton describes a recognizably authentic recipe for macaroni and cheese she calls “Maccaroni à la Reine.”

She bathes her macaroni and its cheese in either “good cream” or a buttery “rich white sauce” and seasoned with prototypically English spicing of cayenne and mace. The dish is topped with toasted breadcrumbs and baked in the oven. It stands comparison with any twenty first century iteration of the dish, especially if its cook uses an ingredient Miss Acton suggests:

“A portion of Stilton, free from the blue mould, would have a good effect in the present receipt.” (Acton 393)

White Stilton still is produced today and like its more famous sibling is an extremely distinctive cheese. As for the name, by 1845 English authors and chefs were labeling anything, even roast beef and the English puddings unknown to France, as French.

Finally, an extreme outlier, also from London but decades later 1913 amounts to a tantalizing tease. Ada T. Pearson includes a recipe for ‘cheese pudding’ presented immediately before ‘macaroni with cheese’ in her Handbook of Practical cookery for School and Home. In common with all the recipes in the Handbook they are presented without attribution or explanation.

What sets apart Pearson’s pudding recipe apart from all the others under consideration is a single, distinctively North American ingredient not ordinarily found in the British kitchen; ‘Indian,’ or cornmeal instead of the customary macaroni. Other than the substitution, the two recipes are essentially identical with only minor variation (skim as opposed to whole milk for the pudding and the option to use dripping instead of butter). Both are baked. (Pearson 96)

If Pearson referred to the dish as a pudding because of the presence of the cornmeal, and there is no other explanation why she did, then she may have used the term to differentiate it from the traditional British template for macaroni and cheese. And because cornmeal was (and is) a product inextricably identified with North America in Britain, its usage may refer to a similar antecedent there if not necessarily a pudding made with macaroni. All that is of course only speculative syllogism.

11. A reluctant recruit.

It turns out that for several reasons including this lineage, Miller had misgivings but not regrets about including macaroni and cheese among the iconic soul foods he describes in Soul Food.

For one physiological thing, West Africans, according to Miller, have a predisposition to lactose intolerance and for that reason cooking derived from African technique nearly never involves milk products including cheese. (“Cheese IQ”)

In the 2017 interview he discloses that

“I wasn’t going to include macaroni and cheese in my book because it has such a clear European provenance that I didn’t think there was a unique African-American angle.”

Why then did he include the dish? Not for any reason related to solid research or scholarly accuracy. “I got so much peer pressure from my African-American friends,” he admits,

“that I just buckled to peer pressure and included it in the book.” (Graber)

So by 2017, macaroni and cheese had indeed become black, as Miller’s friends would attest, and is no less authentically African American for its English ancestry so he has no regrets about discussing the dish in Soul Food after all. (Soul Food 130) We should not, however, throw ourselves into contortion to create an inauthentic origin myth.

Here it is again. Enjoy.

Here it is again. Enjoy.

Macaroni and cheese also is perennially popular with most Americans, Canadians as the adoption of ‘Raffald’ infers and for that matter British people of varied ethnicities. None of us can claim it as exclusively ours. The proliferation of recipes not only online but also in print, infinite variations on a homely theme, places the preparation in the public domain. It is incidentally a public house staple in Britain, and if public houses manage a return after the plague passes, should be the kind of comfort food customers crave.

All this traffic in possession and repossession, like the times in which we find ourselves on so many fronts, is more than passing strange. The notion that any dish, in particular a popular palimpsest like macaroni and cheese, could become a battle in the culture wars to divide instead of unite us, should give anyone pause. After all, to paraphrase a discredited psychiatrist, sometimes macaroni and cheese is just macaroni and cheese.

The bfia recipe and others for macaroni and cheese appear in the practical.

Sources:

Eliza Acton, Modern Cookery, for Private Families (London 1845)

Anon., “James Hemings 1765-1801: Master Chef, Culinary Innovator, Teacher, Maître D’hôtel, Valet, Slave, American,” http://www.jameshemingssociety.org/james-hemings/ (n. d.) (accessed 2 June 2020)

Anon., “History of Cheese,” National Historic Cheesemaking Center, https://www.nationalhistoriccheesemakingcenter.org/history-of-cheese/ (n.d.) (accessed 14 July 2020)

Anon., “Origin of a Dish: Macaroni and Cheese,” Four Pounds of Flour, http://www.fourpoundsflour.com/origin-of-a-dish-macaroni-and-cheese/ (7 January 2010) (accessed 3 June 2020)

Anon., “Raffald (Mac & Cheese),” Prairie oils & vinegars, http://www.prairieoils.ca/blogs/recipes/raffald-mac-cheese (n. d.) (accessed 31 May 2020)

Anon., “Thomas Jefferson’s Notes on Macaroni and the Macaroni Machine,” https://www.monticello.org/site/research-and-collections/macaroni (n. d.) (accessed 1 June 2020)

Neil Buttery, “Macaroni Cheese,” British Food: A History, https://britishfoodhistory.com/elizabeth-raffald/ (3 February 2019) (accessed 14 July 2020)

‘Chopbreak Cooking,’ “6 Origin Stories of your Favorite Modern Foods; Mac and Cheese,” www.chopbreak.com/6-secret-origin-stories-of-modern-foods.html (3 September 2020) (accessed 11 July 2020)

Derek Coleman, “Mac and cheese dish dates back thousands of years,” the Huntington, West Virginia, Herald Dispatch (11 May 2018)

Alyssa Connell, “Maccarony Cheese,” Updating Early Modern Recipes (1600-1800) in a Modern Kitchen, https://rarecooking.com/2014/06/30/maccarony-cheese/ (30 June 2014) (accessed 16 July 2020)

Thomas Craughwell, Thomas Jefferson’s Crème Brûlée: How a Founding Father and His Slave James Hemings Introduced French Cuisine to America. (Philadelphia 2012)

Bill Daley, “How America developed its taste for mac and cheese,” Chicago Tribune (21 May 2016)

Alan Davidson (ed.), The Oxford Companion to Food (Oxford 1999)

Catherine Donnelly (ed.), The Oxford Companion to Cheese (Oxford 2016)

Loyal Durand Jr., “The Migration of Cheese Manufacture in the United States,” Annals of the Association of American Geographers Volume XLII Number 4 (December 1952) 263-82

Gordon Edgar, “A Brief History of America’s Appetite for Macaroni and Cheese,” Smithsonian Magazine, https://smithsonianmag.com/history/brief-history-americas-appetite-for-macaroni-cheese-180969185/ (29 May 2018) (accessed 1 June 2020)

Conor Friedersdorf, “What’s Leafy, Green, and Eaten by Blacks and Whites?” The Atlantic (22 January 2016)

Michael Gebert, “Seeing the soul food in American cuisine’s mirror with author Adrian Miller,” the Reader (Chicago) (19 May 2014)

Cynthia Graber et al., “Who invented macaroni and cheese?” www.http://gastropod.com/who-invented-macaroni-and-cheese/ (13 November 2018) (accessed 1 June 2020)

Karen Hammonds, “Macaroni and Cheese,” Revolutionary Pie, https://revolutionarypie.com/2013/10/20/macaroni-and-cheese/ (20 October 2013) (accessed 2 June 2020)

Amanda E. Herbert, “Mistranslating Macaroni and Cheese,” The Recipes Project, https://recipes.hypotheses.org/10510 (n. d.) (accessed 19 July 2020)

Constance Hieatt & Sharon Butler, Curye on Inglish: English Culinary Manuscripts of the Fourteenth-Century (Including the Forme of Cury) New York 1985; www.godecookery.com/grec6.htm (accessed 13 July 2020)

N. Holifield, “The Hidden History of Macaroni and Cheese,” Tangie’s Kitchen, https://www.qnholifield.com/culinary-history/the-hidden-history-of-macaroni-and-cheese/ (n. d.) (accessed 31 may 2020)

Judith & Evan Jones, The L.L.Bean Book of New New England Cookery (New York 1987)

Corby Kummer, “Pasta,” The Atlantic (17 November 2013)

David Lee, “British-Inspired Bahamian Dishes,” https://www.hgchristie.com/blog/2014//08/05/british-inspired-bahamian-dishes/ (5 August 2014) (accessed 1 June 2020)

Emma Loveland, “The History of Macaroni and Cheese,” http://www.faculty.etsu.edu/odonnell/2019fall/engl1010/bestessays/History_of_mac_and_cheese_Emma_Loveland_.pdf (Fall 2019) (accessed 13 July 2020)

Ashbell McElveen, “James Hemings, Slave and Chef for Thomas Jefferson,” The New York Times (4 February 2016)

Adrian Miller, “Cheese IQ: A Side of Soul,” Culture: the word on cheese (20 June 2016)

Soul Food (New York 2017)

Tara Okwemba, “The History of Slavery in the Cultivation of Mac & Cheese: From Elitist Dish to Cultural Staple,” https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/03dbf30ccd245b0a505f18b18fb5e8c/print (23 December 2019) (accessed 2 June 2020)

Ada T. pearson, A Handbook of Practical Cookery for School and Home (London 1913)

Blake Perkins, “Authenticity and Appropriation--The Southern United States and Scotland,” Petits Propos Culinaires 116 (March 2020) 26-45

Richard Posner, The Little Book of Plagiarism (New York 2007)

Elizabeth Raffald, The Experienced English Housekeeper (orig. publ. London 1769; Southover Press edition 1997)

Mary Randolph, The Virginia-Housewife: or Methodical Cook (Washington DC 1824)

Joe Rhinehart, “Origin stories of macaroni and cheese, recipes to try,” https://www.news-graphic.com/news/origin-stories-of-macaroni-and-cheese-recipes-to try/article_81a02c42-4a59-11e8-a311-63c6c09460ff.html (28 April 2018) (accessed 7 July 2020)

Silvano Serventi & Françoise Sabban, Pasta: The story of a universal food (New York 2002)

Keith Stavely & Kathleen Fitzgerald, United Tastes: The Making of the First American Cookbook (Amherst MA 2017)

Toni Tipton-Martin, “Collard greens and macaroni cheese: African American food classics--recipes,” The Guardian (4 July 2020)

Jubilee (New York 2019)

Michael Twitty, “The roots of black Thanksgiving: Why mac and cheese and potato salad are popular,” The Washington Post (17 November 2016)

Korky Vann, “Church Suppers: Comfort Food and Tradition,” the Hartford Courant (3 August 2010)

William Woys Weaver, 35 Receipts from “The Larder Invaded” (Philadelphia 1986)

Clifford A. Wright, “Origin of ‘Macaroni and Cheese,’” http://www.cliffordawright.com/caw/food/entries/display.php/topic-id/16/105/ (n. d.) (accessed 11 July 2020)

Mark Zanger, “Macaroni and Cheese” in Andrew F. Smith, The Oxford Companion to American Food and Drink (New York 2007)