More than the dude abides, at least in Dublin if no longer in Bolton across the Irish Sea, being a meditation on Neary’s & Flann O’Brien, with a digression on the first Bloomsday.

-by Anthony Lamont

1. No compromise with the twenty-first century.

No music, live or otherwise, no television, no gambling machines. No guest beers, no daily specials, no artisanal cocktails. No advertising nor slinky barmaids; no female staff at all.

If Guinness has fallen from favor in relative terms, traditional stout from the Liberties remains the standby here. The place retains four of the last indoor gaslights in Ireland, its marble bartop, its snug (only one, but then every other public house in the republic seems to have torn theirs out), its sparing nod at visual art, the iron arms outside holding lanterns to beckon custom. A dumbwaiter serves the cellar kitchen. Neary’s would merit protected status for the lift alone. It is a treagle made in 1957 by Wm. Wadsworth & Sons in Bolton.

2. A detour across the narrow sea.

Wadsworth, as a promotional brochure from 1918 proclaimed, manufactured “Lifts and all Hoisting Miscellanea.” The firm would become an industrial legend, along with Otis and several German firms the leading global innovators in elevator design for a century.

In 1864, William Wadsworth had begun his business repairing belted looms and other equipment in the booming cotton mills of Manchester and environs including, of course, Bolton itself. When his sons joined him in 1891 they began to build “worm gear hoists and the self-loading transporters that were to become famous for moving material directly between floors and wagons or trucks.” Wadsworth also was famed for the huge lifts it made and installed 90 feet under the Mersey for serving what had been the first underriver crossing in the world.

By the 1970s Wadsworth had adapted to foreign competition from lower wage countries by developing ‘one off’ custom elevators including, for examples, “a pair of 30-ton oil hydraulic freights with magnetic door ‘grips’” and “explosion-proof winding gear for gas holding tanks.” (elevatormuseum.org) The storied enterprise had finally succumbed to English deindustrialization by 1986.

Other than a surprising amount of extant equipment on London Underground, Wadsworth elevators and their components--including anything etched with the company name--have become rare, even collectible within the eccentric world of elevator enthusiasts.

3. Unmistakable Ireland.

At Neary’s the Wadsworth treagle lifts food, extremely good food, from a short, alliterative selection of sandwiches, salad and soup--nothing more except, sometimes, oysters in season--and only from 10:30 am until 2:45pm, but never on Sunday. If food were its only draw, Neary’s would be worth a trip from far away. The public house offers exemplary brown, white and, yes, soda bread; poaches its own salmon; roasts its own beef; and obtains its food from superior sources, including smoked salmon from the celebrated Wright’s of Howth, where they have oak smoked and hand cut their fish since 1892.

Neary’s itself dates a bit farther back, to 1887. The Irishry of the place is ineffable without any taint of sentimentality or chauvinism, or anyway not too much, and yet like so much that is Irish bears a certain English cast. It is, ironically enough, situated on Chatham Street, and it was Pitt the Younger who bribed the Irish Parliament to commit suicide in 1800. The Union may not have been a bad bargain but for the broken promise of Catholic Emancipation, but that was the fault of a fickle mad king, not of Pitt himself. Still, a wizard should have known better.

The treagle quite obviously is English, like the cast of the food it conveys, because most Irish foodways emigrated from across the Irish Sea. Ghosts of Anglo-Ireland also haunt Neary’s in its whiskey and beer, the founding Bushmills, Jamesons and Guinnesses protestants all.

4. Sense and sensibility.

Always described as ‘Victorian,’ Neary’s is not quite so, the most austere and best of Dublin’s storied nineteenth century public houses. The atmosphere is all Arts and Crafts, more William Morris than George Gilbert Scott. The movement could not have been more English in its adoration of the artisanal and distaste for the industrial esthetic although, another apparent anomaly, the style also stormed California.

Spare paneling frames subtle wallpaper, the same buffed wood shelters mirrors round the upper reaches of the main room and the furniture is plain in the approving Anabaptist sense. A couch punctuated by low tables and padded stools forms a composition along the length of the wall opposite the bar. It is all low key, comfortable, even sort of serene. Neary’s is nothing if not a niche for lively conversation.

5. Constellations of conviviality.

More than its décor, sensibility and dumbwaiter tie Neary’s to an appealing past. It is, its website claims, “a UNESCO City of Literature bar,” but while Dublin itself has earned the urban accolade, UNESCO does not appear to classify bars as anything at all. If, however, the designation did exist, then Neary’s would earn charter membership in the guild.

The notion of literary Dublin is not just an example of Irish bunkum, as Nuala O’Faolain explains. “Biographers of Irish writers will be scraping the barrel very deep,” she maintains with more modesty than truth,

“if they ever come to me. But I’m representative of a certain milieu. For every real writer around, there were ten merely literary-minded people like me. Perhaps ‘literary Dublin’ needed both kinds. It was a real place, even in the 1960s. Without question, writing mattered more than money or possessions or status in any other field. But the culture was terribly dependent on drink.” (O’Faolain 75-76)

And despite her profound misgivings about booze, the tragedy of anyone “being a drunk,” of “waking to the evidence of repeated lonely humiliations, that drive you further and further away from anything but drink,” O’Faolain understood the importance of the public house itself. (O’Faolain 76) Frank McCourt recalled that when asked by anyone where to find “the real Ireland,” she invariably replied “The pubs. Go to the pubs, and go often.” (O’Faolain x)

The history of Neary’s encompasses not only literature and the press but also theater and film. A portal past the toilets opens onto the stage door of the adjacent Gaiety Theater, and even has borne traffic from actors seeking refreshment midplay. One of them, Alan Devlin, left HMS Pinafore in a rage following the first act, unaware that his microphone remained live. “Devlin,” Tom Sweeney recounts, “resplendent in his admiral’s uniform, drew his sword and called for a pint.” He also railed at the quality of the production (“Fuck this for a game of sailors…. ”) for the regulars. They knew him well enough: Before being barred for bad behavior, Devlin had been a regular himself. (Sweeney)

Gaiety Theater

6. Myles and company.

At midcentury they could include, among many others, literary lions tinged with tragedy like Austin Clarke, Anthony Cronin, Patrick Kavanaugh, Thomas Kinsella and John Ryan (nearys.ie) but not, after a time, Brendan Behan. His dangerous and destructive drunkenness made him non grata in any Dublin drinking establishment, although he harbored a particular animus for Neary’s where, he maintained, “the common hangman drank.” (Ryan 135) Other opinions also cast doubt on Behan’s judgment. He insisted, for example, that Guinness got its deep color from the water used to brew it: “Pull the chain and in a jiffy, the shite is floating down the Liffey.” He and so many more of his generation in Austerity Ireland had lived straightened lives defined as much by alcohol as genius and had died too young.

Best and perhaps saddest of all however was the man born Brian O’Nolan; that is, Brian O Nuallain the precocious student and literary prankster; Brian Nolan the Joyce scholar and spoofer; Flann O’Brien the novelist and ‘poet;’ Myles na gCopaleen or Myles na Gopaleen, the satirist, playwright and journalist; and a number of less frequently used pseudonyms including Brother Barnabas, Count Blather, An Broc, John James Doe, Matt Duffy, George Knowall, Count O’Blather, Lir O’Connor and probably John Seamus O’Donnell, many but not all employed to draft crank letters to the Irish Times attacking any number of items in the paper .

A man and his hat.

O’Nolan had signed one letter, “a devastating broadside” aimed at Michael MacLiammoir and Hilton Edwards, the producers of a play then running at the Gate theater, as ‘Hazel Ellis,’ a nearly unknown Irish playwright. “The real Hazel Ellis,” however,

“rushed into print with a disclaimer, explaining that she was an ardent admirer of Messrs Edwards and MacLiammoir, whereupon Brian O’Nolan immediately replied (again using the name Hazel Ellis) denouncing this lady as ‘an obvious imposter.’”

R.M. Smyllie, the legendary editor of the Irish Times , realized in 1940 that in fact the same person had written all the letters, and found them so impressive that he determined the author’s identity and offered O’Nolan a column. Once they met, Smyllie liked him as well as his writing, but the editor may have been motivated in part by self-preservation.

According to Tony Gray, a journalist who started at the paper when the ‘Ellis’ correspondence was underway, the artificial controversies had made Smyllie “extremely nervous and for weeks seemed highly suspicious of every letter… published in the correspondence columns.” (Gray 109) Admitting that the letters had been “vexing” him “greatly over the past few months,” Smyllie solved the problem by hiring O’Nolan. “If,” he explained,

“we pay the bugger to contribute to this shuddering newspaper, he may no longer feel tempted to contribute gratis, under various inscrutable pseudonyms, to the correspondence columns.” (Gray 109-10)

In the event the tactic failed: O’Nolan continued to attack articles in the paper (including his own column) under a variety of fictive names over the course of his long career.

Many of the early columns and a number of the later ones appeared in Gaelic. O’Nolan was one of the few people in the modern era proficient in the language, but he disdained the decrees making its instruction mandatory, and requiring documentation and signage in Irish as well as English. Nobody outside the shrinking western Gaeltacht, or too few individuals to make an impact, was sufficiently proficient to teach the language with any competence, and the revivalist killjoys themselves tended to intolerance, bigotry and censorship.

O’Nolan hated the “pietistic chauvinists” of the Gaelic League, “old pedants obsessed with the fear of sex and beauty,” while, as he wrote in 1957, the government publishing enterprise produced

“ ….a downpour of novels, poems, essays, plays in Gaelic; scarcely a soul buys them because they are composed chiefly of embarrassing dreeder and prawnshuck.” (Ryan 160; Cronin, No Laughing Matter 123)

He liked the language and could make it sing, but also understood that a small nation intent to foreswear a nearly universal language in favor of one no one else understood would be doomed to permanent poverty. For him, however, Gaelic served another significant function.

de Valera

Although a civil servant himself, O’Nolan deplored the censorship, moral as well as political, imposed by the “narrow-minded” de Valera regime (Gray 17, 18), and because the censors themselves understood as much, or little, Gaelic as the brunt of the population, he could get just about anything written in the language past them, ranging from pranks involving plays on the word ‘penis’ to attacks on the government and church.

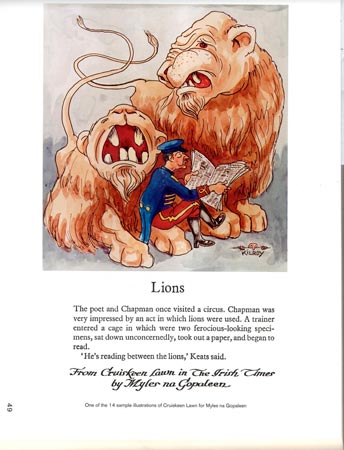

“Cruiskeen Lawn” (“full jug” in Gaelic) would become one of the finest series of comic commentaries ever published by any newspaper anywhere. Added to the inscrutable genius of At Swim-Two-Birds and The Third Policeman along with The Poor Mouth , which originally appeared in Gaelic as An Beal Bocht and ranks as the best of modern satires deriding the Irish proclivity for self-pity and de Valera’s risible notions of rural idyll, the column cements O’Nolan as one of the less appreciated literary figures of the twentieth century.

Hugh Kenner considers O’Nolan a wasted talent. “Was it the drink was his ruin,” the critic wonders, “or was it the column? For ruin is the word. So much promise has seldom accomplished so little.” (Kenner 255) The appraisal is unjust. “Cruiskeen Lawn” was not the ruin of O’Nolan but rather encapsulates the enduring manifestation of his warped genius. This, after all, was someone who instructed his reader to overcome wartime shortages by making jam from “used electricity.”

There was in addition a most serious side to O’Nolan. “The chastisement of the folly and hypocrisy of modern Ireland” became, recalls Ben Kind, his vocation. Writing nine years after O’Nolan’s death, Ryan insisted that “the fear of his ridicule still hangs over the corridors of power.” (Ryan 131)

“The Brother,” his “single, all-purpose Dubliner” along with “The Plain People of Ireland,” became frequent figures along with ‘poets’ Keats and Chapman in the column, and O’Nolan employed them “during that first heady morning of Nationhood” to lampoon “their manners and mores, vices and virtues, the incredible posturings and grotesque ‘patriotic’ antics of the founding fathers, the proliferating tangle of bureaucracy that envelop[ed] the nouveau Irish…. ” (Ryan 129) As Allen Barra notes, “Cruiskeen Lawn” savaged one chauvinistic seminar as “a virulent eruption of paddyism.” (Barra)

7. Food in the employ of scurrilous fiction.

Sometimes O’Nolan referred to food without reference to used electricity, and in particular to its lack of palatability in the Ireland of de Valera. One of the stories Ryan recalls involved a con artist named Kelly who sought to circumvent the “immense tariff wall” of the Irish Free state by obtaining a monopoly to assemble an obscure model of car from eastern Europe. Kelly and his equally unscrupulous sons have no assets but manage to lure the owner of the company to Dublin. They borrow a big Hispano-Suiza to meet his Focke-Wulf at “an Irish Army flying field” and take him to Dublin where they treat him to a “banquet” of “tinned grapefruit, tomato soup, roast chicken, ham, and colcannon, sherry-trifle and different coloured wines,” typical enough of what passed for haute cuisine in interwar Ireland, although to be fair roast chicken with ham and colcannon both represent traditional Irish foodways.

After lubricating their guest, the conspirators bring him to “some small alley off Little Britain Street” where

“Kelly produces a key and opens the door of a corrugated iron lean-to shed in an advanced state of decomposition--its sole occupants a venerable lady’s upright bicycle and a one-eyed tom-cat.”

The shed, Kelly assures the mogul, “is where we are going to assemble the cars.” Unimpressed either by food or facility, he screws a monocle into his eye and responds “It iss in mine arse” and flies away. (Ryan 134)

The debilitating protectionism, the food described, the transparent bluff, the street name, the bicycle (also a recurring trope of O’Nolan as O’Brien) and ramshackle structure all symbolize provincial and hapless Irish efforts to ape the English they despise. The parody of cultural and economic conditions never would have survived the censors.

The Hard Life: An Exegesis of Squalor , set from 1890 to 1910, savages false piety; Catholic complacency; Catholic and Irish corruption and hypocrisy; Irish poverty, prudery, sentimentality and empty verbosity; Irish and English relations; the supercilious English (Scots seem exempt); sexism; and even takes a swipe at Irish foodways.

Colcannon, but not as nasty as O’Brien describes.

O’Brien describes any number of ghastly dishes, beginning with the food foisted on the two boys at the center of the book by the “streel of a girl with long lank fair hair” who arrives to take care of them after they have been deserted by both parents. Her family and acquaintances consider her pious and retiring, but the younger brother later learns that she moonlights, quite literally, as a streetwalker down by the canal. “Was,” he wonders after the discovery, “the nature of sexual attraction…. all bad and dangerous?” ( Hard Life 110, 111)

During the day she

“spent a lot of time washing and cooking, specializing in boxty and kalecannon and eternally making mince balls covered with a greasy paste…. If we’re ever sent to jail, the brother said one night in bed, we’ll be well used to it before we go in. Did you ever see the like of the dinner we’re getting?” ( Hard Life 11-12)

Their breakfast invariably was stirabout, a thin gruel of cornmeal or oatmeal that also appears as the miserable narrator’s grim breakfast in the short story Black Peter along with “twelve nettles, lovely nourishing nettles that do b on the bog.”

This contrasts to the Good Old Days. The older brother again:

“-How well the mammy thought nothing of a bit of ham boiled with cabbage once a week. Remember that?

-I Don’t. I hadn’t any teeth at that time. What’s ham?

-Ham? Great stuff, man. It’s a class of red meat that comes from the county Limerick.” ( Hard Life 12)

The older brother’s blithe misdescription prefigures his career. He will escape the squalor of Ireland to England and “pursue, with some success, a host of elaborate and fraudulent schemes.” (Updike) “An Irish address,” he explains, “is no damn use. The British dislike and distrust it. They think all the able and honest people live in London.” ( Hard Life 64)

The younger brother is not much more reliable. Within the space of a single page he confesses that he “got to hate” the mince balls while insisting to his sibling that “they’re all right” and warning the reader about his recollection of the conversation concerning the mince balls and ham: “Probably it is all wrong.” ( Hard Life 12) Nothing and no one in the worlds created by O’Nolan is reliable, as he wrote (in the guise of o’Brien) to Wiliam Saroyan about The Third Policeman ; “none of the rules and laws (not even the law of gravity) holds good…. ” (Updike)

Eventually the boys move in with a garrulous benefactor, the streel’s father, who becomes an inadvertent martyr to one of the older brother’s scams after ingesting his Gravid Water in an effort to cure rheumatism. It causes his weight to balloon, all the way to 406 pounds. There goes that law in The Hard Life as well. Until then the benefactor had inhabited “a meagre frame” reflected by his name, Mr. Collopy; a collop is British and Irish usage for a thin piece of meat.

Mr. Collopy visits public houses but not, from his description of their food, Neary’s. He considers Dublin publicans “pishrogues” who

“ ….water the whiskey and then give you short measure. They give you a beef sanrwich with no beef in it, only scraws hacked off last Sunday’s roast by the mammy upstairs with her dirty hands. Some of those people don’t wash themselves for weeks on end and that’s a fact.” ( Hard Life 53)

Mr. Collopy (nobody ever drops the title or knows his given name) spends his evenings drinking whiskey and engaging in pointless polemics with his friend Father Fahrt, an obtuse German Jesuit. The priest, “being of continental origin, understood everything perfectly and did not need advice on any matter.” “An humble Jesuit,” Mr. Collopy rages, “would be like a dog without a tail or a woman without a knickers on her. Did you ever hear tell of the Spanish Inquisition?” He insists to Fahrt that its Shock Troops drove “red-hot nails into the backs of unfortunate Jewmen,… scalding their testicles with boiling water” and “ramming barbed wire or something of the kind up where-you-know.” ( Hard Life 123, 35)

The “lot of crooked Popes with their armies and papal states, putting duchesses and nuns up the pole and having all Italy littered with their bastards,” Mr. Collopy insists, are even worse than Jesuits. ( Hard Life 37)

Fahrt and Mr. Collopy do agree on something. The English, at least in London, unfortunately “look for hard work. From the Irish anyway.” The older brother demurs. Fleeing Sergeant Driscoll of the Dublin Metropolitan Police, he announces to an astonished Mr. Collopy: “I’m damn glad I’m clearing out. Give me a blood-thirsty and depraved Saxon any day.” ( Hard Life 79, 92)

The police, he insists, would “swear a hole in a bucket. They all are the sons of gobhawks from down the country,” and particularly from Kerry, a culinary wasteland:

“The banatee up at six in the morning to get ready thirteen breakfasts out of a load of spuds, maybe a few leaves of kale, injun meal, salt and buttermilk. Breakfast for Herself, Himself, the eight babies and the three pigs, all out of the one pot. That’s the sort of cods we have looking after law and order in Dublin.” ( Hard Life 91)

When the streel of a girl offers to make “hang sangwiches” for the improbable hegira of Fahrt and Mr. Collopy to the Vatican to beg assistance from the Holy Father for Mr. Collopy’s mission to provide public toilets for the women of Dublin (Fahrt during their evening arguments: “Never mind that subject.” In the event the pope told them “to go to hell.”), Mr. Collopy pours scorn on the proposal. ( Hard Life 123, 133)

He counters by describing the universal Irish aspiration for plain meat and potatoes with ‘two veg.’

“A damn good dinner. Sirloin, roast potatoes, asparagus, Savoy cabbage and any god’s amount of celery sauce. With, beforehand, mushroom soup served with French rolls. With a bottle of claret, the chateau class, beside each plate.”

In characteristically fatuous form, Fahrt does not “find that meal very homogeneous” while conceding “well, it would hardly kill you.” ( Hard Life 124)

Keith Hopper in the New Statesman considers “Cruiskeen Lawn” an incomparable resource for historians of midcentury Ireland, “a mosaic portrait of the country’s everyday madness.” (Hopper) The same may be said of both The Hard Life and The Poor Mouth , in which miserable peasants in the countryside lament:

“In one way or another, life was passing us by and we were suffering in misery, sometimes having a potato and at other times having nothing in our mouths but sweet words of Gaelic.”

O’Nolan himself considered his work no such thing; “an enemy of pretension and cant, he undermined most claims to importance--his own most assiduously of all.” (O’Neil)

8. Becoming Myles.

O’Nolan would become the fictive persona of his column even to the extent his friends all took to calling him Myles. Ryan for one is unequivocal. “Myles was a prodigy. His erudition was frightening and indeed many were frightened by it.” (Ryan 127) His erudition extended to unlikely expanses. He knew, according to several sources, more than many engineers about steam engines. ( e.g. Updike) For all we know O’Nolan knew as much about the Wadsworth treagle at Neary’s as its owners.

O’Nolan mined all the knowledge to make readers laugh but also to delve into deeper inquiry. As Joseph O’Neil recognizes, “his comic genius drew him helplessly into the profoundest theoretical concerns and, once there, to an amazing prescience.” (O’Neil)

Ryan also understands that his personality was complex.

“Myles, that figment… of his own imagination, was the greatest comic genius we ever produced, but beneath a plentiful, fertile topsoil of wit lay a stratum of sorrow which… provides the essential ingredient for growth.” (Ryan 158)

Other giants of midcentury Dublin agreed.

“Patrick Kavanagh, who threw compliments about like a man with no arms (viz: ‘Yeats? I could do without him ’) called him ‘the incomparable’ …. It was linked in his mind with ‘irreplacable’.” (Ryan 127)

Cronin wrote a biography of O’Nolan laced with acid. Cronin, who like the older brother in The Hard Life escaped to London, himself was in general guilty of the “begrudgery” he found so distasteful in what he considered the hopelessly provincial literary circles of midcentury Dublin. Even he, however, had to admit that “Cruiskeen Lawn” was “unfailingly brilliant and brilliantly adjusted to its Dublin audience.” ( Dead 116)

‘The incomparable’ slaked his sorrow with drink, and his drinking became legendary too. Ryan was a painter, memoirist and editor of the journal Envoy ; it lasted but two years as an intended antidote to the cultural, moral and political censorship imposed and philistinism promoted by the Irish government. He has been described as a “literary publican” (Ryan bought the fabled Bailey in 1956 or 57; accounts vary) and explains that O’Nolan’s “haunts were many and varied but principally I would come across him in Neary’s.” (Ryan 135) Michael O’Regan adds that “Flann O’Brien could be heard in Neary’s… on any subject known to man.” (O’Regan)

“Myles,” Cronin was “convinced, was a true alcoholic, with a physiological need for alcohol. Signs on, he was a sober drinker, meticulous and methodical.” “[M]eticulous and correct” in other ways as well, O’Nolan “did not believe that being an author conferred the privileges of being rude and offensive to others not of that calling.” (Ryan 161) He liked to buy rounds for his friends and despised those like Behan who did not. ( Dead 119)

Brendan Behan, the anti Myles.

O’Nolan’s father died early, and Myles supported ten siblings and his mother for many years. He was a faithful if neglectful husband--“sexual promiscuity was abhorrent to him”--and he paid his property taxes, or rates, in advance, while “the idea of ever paying rates, if they could by any manner or means be avoided, would be as alien to Kavanagh or Behan as going on the dry for life.” (Ryan 161)

While admitting that the drinking “got progressively worse” one acquaintance describes O’Nolan as a ‘drinkard’ rather than drunkard who enjoyed the sociability of the public house. (Rennicks) How much worse is hard to quantify. As his nephew observes, O’Nolan never missed a deadline at the Irish Times and he rose through the civil service to become Private Secretary to Sean MacEntee, the Minister for Local Government and powerful political figure in the young republic. He did not, the nephew believes, spend as much time in the public house as presumed. (Kennedy)

A post in the civil service was a prestigious position in the impoverished Ireland of the time. Candidates were selected by examination, the salary was good and the ethos apolitical, which could have caused O’Nolan considerable trouble and may explain his fondness for fake names.

He died one April Fool’s, which must have pleased him, although he died too young from debilitation due to all the drinking. According to Ryan, the loss was insurmountable for some. He recalled that Kavanagh

“survived Myles by a little more than a year, but even in that short period often remarked to me that there really was nobody left to talk to in Dublin now that Myles was gone.” (Ryan 127)

9. Long days’ journeys.

Before the demise he had bequeathed another sort of literary legacy to the Irish and the world. On 16 June 1954, exactly five decades after the day Joyce set Ulysses , O’Nolan staged the first Bloomsday. Inevitably he already had asked, as Myles in his column: “Who can be answerable for James Joyce if it not be the Jesuits?” and his appreciation of Joyce did not dim. Ever a master of misdirection, O’Nolan that day had attacked Joyce as illiterate for misusing foreign phrases. (Lynch)

The original Bloomsday was not the tourism bonanza it would become. John Garvin, a participant and himself a civil servant compelled by the strictures of the time to write under an alias, Andrew Cass, about Joyce, described it as a “pilgrimace,” in Ryan’s characterization “being a pilgrimage, a grimace and, to some extent, a disgrace.” (Ryan 138) Reporting on the fiasco, O’Nolan’s own newspaper wrote that

Inspiration for the “pilgrimace”.

“the oddest ‘pilgrimage’ Dublin has ever seen took place…. In a vintage cab Joyce devotees and one distant relative of the writer visited all the places mentioned in the book to mark the 50th anniversary of ‘Ulysses day.’ The rest of Dublin took no notice.” ( Irish Times , 26 June 1954 )

The Irish Times was not quite right, although in 1954 Joyce did remain anathema in the official as well as popular circles, cultural and political, of the Ireland he chronicled and despised. The pilgrims, however, did not manage to visit all the places, and not all of Dublin took no notice on that first, or fiftieth, year. The procession began below the Martello Tower in Sandycove where Ulysses begins. O’Nolan had hired two of what might only with the utmost charity have been described as vintage cabs, a couple of anachronistic ‘broughams,’ “which in Ulysses Mr. Bloom and his friends drive to poor Paddy Dignam’s funeral.” (Costello) O’Nolan’s conveyances were

“two splendidly decrepit examples, all black and verdigris, straw stuffing bursting through the upholstery and the indispensable ‘jarveys’ with watery eyes and noses that they had spent a lot of time and money colouring.” (Cronin 138)

The jarveys were not the only drunks that day. O’Nolan showed up drunk on the morning he had appointed for the procession, and whether or not his cohorts arrived that way they soon followed suit. The idea had been to make a stop related to each chapter of the book, but in the event the celebrants only made it to “Lestrygonians” and Duke Street before, Ryan recalls, “communications became unreliable, transport broke down and the strict order of procedure was permitted to lapse.”

Other members of the procession included Cronin; Cass or Garvin; Tom Joyce, a cousin of the author; Kavanagh; and Con Leventhal, “being Jewish, meant to symbolize Bloom.” As they lurched through Dublin, Ryan also remembers, the “two-carriage progress soon became a cavalcade as numerous other vehicles tagged on behind.” In a serendipitous turn, Duke Street was the locale of the Bailey, famed literary public house (and feature of Ulysses ) and haunt of the Bloomists so the rabble retired there to drink and argue as usual. (Ryan 138, 139)

A modest modern metafiction.

10. The black hats.

De Valera unwittingly had reinforced the public house culture he decried. His obsession with autarky nearly outlawed foreign capital, so “the almost non-existent Irish economy” did not support much business or industry at midcentury. (Gray 17; Cronin, No Laughing Matter 111) Censorship made most forms of entertainment other than theater lifeless much of the time, and television came late to the country. To a significant extent the Clarkes, Kinsellas, O’Nolans and Smyllies of Dublin had little to do but head for a bar, in O’Nolan’s case sometimes from morning until midafternoon.

Cronin writes with a sniff that Smyllie cut a “portly figure who was large in his physical dimensions at least,” and even though “his own writings were negligible,” the editor “wore the large black hat which was the standard uniform of the Dublin man of letters.” (Cronin, No Laughing Matter 111)

The writers for their part were less ungenerous and indulged Smyllie his affectation, most likely because as Cronin himself concedes, the editor of the most influential paper among Irish intellectuals

“then occupied a position of perhaps inordinate importance in the consciousness of literary Dublin, and was central to its myth of itself as a place where heavy drinkers who were also wits consumed many hours of each day in literary converse enlivened by anecdote and epigram.” (Cronin, No Laughing Matter 110).

The irony that their hats entailed is irresistible. Whether, or probably not, the literati had determined to emulate the Iron Brigade, their own uniform might as well have been from Civil War Wisconsin because secular haberdashers in Dublin did not stock them. The pagans at Neary’s and other public houses “therefore had recourse to a clerical outfitters… which supplied them to old-fashioned Parish Priests from the country.”

Even so dedicated a nonconformist as O’Nolan coveted the big black hat. Upon the publication of At Swim-Two-Birds , “rather surprisingly, he had bought one. His was not as wide-brimmed as some but it was an assertion all the same that he belonged to the Dublin community of letters.” (Cronin, No Laughing Matter 111)

11. No women please, we’re Irish(men).

Readers may have noted that none of the midcentury luminaries just described hoisting jars of porter or balls of malt at Neary’s was female. The omission is no oversight: The landlord refused women entry until the courts intervened at the outset of the 1970s. Even then and for a number of years afterward he allowed women to drink only from half pints, and two of them cost noticeably more than the full measure. In the middle of the seventies the actor Broderick Crawford bought drinks for me and my companion, now my wife, after we, penurious as we emphatically were, registered dismay at the half-pint policy.

Lamentable as the larcenous practices had been, all is forgiven now that the house has gone the way of historically misogynist fellow travelers like Dartmouth, Princeton and Yale to embrace both, or rather all, sexes. O’Faolain, who maintains she witnessed O’Nolan piss against the counter of the bar in a stupor, drank at Neary’s and these days apparently luminaries like Glenn Close and Lisa Edelstein, have made the bar their local while treading the boards or facing the camera in Dublin. (Sweeney)

Regulars still haunt Neary’s too, and they are more likely to join in strangers’ conversation than to treat them as unwelcome aliens. Garrett, formidable raconteur and diligent bartender (although, unaware of its common lineage with Jameson’s, which he prefers, he does refer to Bushmill’s as ‘English whiskey’), might join lucky newcomers to share his stories of New York--he knows Hell’s Kitchen and its best surviving dive, Rudy’s, where journalism students from the City University Graduate School across the street elbow each other at the bar, duct tape holds banquettes together and hot dogs are free--Chicago, Dublin itself and other indispensable destinations.

A Neary’s afternoon with Garrett

Recent afternoons found L.P. Curtis, Professor of Irish History Emeritus at Brown, local hero to academically inclined Dubliners and resourceful raconteur in his own right, visiting from Vermont to share lunch with friends and stories with Garrett, who also identified the best of the other old public houses in town, among them The Long Hall, McDaid’s and The Palace. Each deserves its drinkers, although The Long Hall pipes in music now; McDaid’s is not so friendly; and the Palace suffers from too many tourists as the result of its proximity to Temple Bar, while the back room smells of ‘drains.’ All three of them, however, do serve the seasonal East India Porter from Guinness on draft, a vast improvement on the decent enough standard stuff that is all they offer at Neary’s.

That, however, along with the exceptional food, is much more than enough, and Neary’s is not just the best bar in Dublin but ranks with landmarks like Dirty Frank’s in Philadelphia, the Dog & Bull in Croydon, the R Bar of New Orleans, or The Wild Colonial in Providence among the best on earth.

Sources:

Anon., editorial, the Irish Times (26 June 1954)

Anon., “WM. WADSWORTH & SONS CABINS & ENCLOSURES,” https://theelevatormuseum.org (n. d.) (accessed 14 April 2017)

Anon., “William Wadsworth and sons,” (22 March 2014) (accessed 14 April 2017)

Anon., www.nearys.ie/ (n.d.) (accessed 28 March 2017)

Allen Barra, “Flann O’Brien: Tall Tales, Long Drink,” The Wall Street Journal (17 March 2011)

Marco Canani & Sara Sullam (ed.s), Parallaxes: Virginia Woolf Meets James Joyce (Newcastle 2014)

Peter Costello, Dublin’s Literary Pubs (Montreal 1998)

Peter Costello & Peter Van Der Kamp, “The First Bloomsday Celebration,” http://members.ozemail.com.au/maelduin/firstbloom.html (n.d.; accessed 16 May 2017)

Anthony Cronin, No Laughing Matter: The Life & Times of Flann O’Brien (New York 1998) Dead as Doornails (Dublin 1999)

Tony Gray, The Lost Years: The Emergency in Ireland 1939-45 (London 1997)

Keith Hopper, “No joy in slight here,” New Statesman (August 2011)

Brian Inglis, West Briton (London 1962)

Vivien Igoe, “Early Joyceans in Dublin,” Joyce Studies Annual 12, 81-99 (2001) 81

Michael Kennedy, “Is it about a bicycle? The story of Brian O’Nolan,” Strabane History Society (n.d.; accessed 2 May 2017 via YouTube)

Hugh Kenner, A Colder Eye: The Modern Irish Writers (New York 1983)

Brendan Lynch, “An Irishman’s Diary,” the Irish Times (15 May 2004)

Flann O’Brien, The Hard Life: An Exegesis of Squalor (London 1990; first publ. 1961)

Nuala O’Faolain, Are You Somebody? (New York 2009)

Joseph O’Neil, “The Last Laugh,” The Atlantic (May 2008)

Michael O’Regan, “An Irishman’s Diary,” the Irish Times (2 January 1999)

Fintan O’Toole, “The fantastic Flann O’Brien,” the Irish Times (1 October 2011)

Stephen Rennicks, “Flann O’Brien” (Part 2), RTE Radio 1 (October 2011; accessed via YouTube 2 May 2017)

John Ryan, Remembering How We Stood: Bohemian Dublin at the Mid Century (New York 1975)

Tom Sweeney, “Ireland: If You Visit Only One Pub in Dublin… Nearys,” http://tomsweeneytravels.blogspot.com (30 August 2012) (accessed 29 March 2017)

John Updike, “Back-Chat, Funny Cracks: The novels of Flann O’Brien,” The New Yorker (11 & 18 February 2008)