A note on the natures & welcome revival of punch.

1. The return to a prime blessing of life.

Innovation is not the only aspect of the cocktail craze. Some that is old also is new again, and traditional British punch has returned to American bars after a century or so of absence. “The most popular and democratic beverage in colonial America,” according to Wayne Curtis, “was rum punch.” (Curtis 114)

According to Larousse Gastronomique, which in 1938 did its best to claim anything edible or potable for France, punch “is said to have originated among English sailors” with a primitive, for punch, mix of “cane spirit,” probably arrack, and sugar in “about 1552.” The most frequently repeated origin myth for the term is the Hindustani word ‘panch,’ for five. As John Foster, a British traveler in India noted during 1673, the “English on this coast make their enervating liquor called Punch from five ingredients;” arrack, lemon, sugar, tea and water. (Curtis 116)

Then the compendium attributes a recognizably early modern punch to the First Sea Lord of the Royal Navy. “On 25 October 1599,” Larousse recounts,

“Sir Edward Kennel, commander-in-chief of the English navy, offered to his ships’ companies a monster punch which he had prepared in a vast marble basin. For his concoction he used 80 casks of brandy, 9 of water, 25,000 large limes, 80 pints of lemon juice, 13 quintals (1,300 pounds) of Lisbon sugar, 5 pounds of nutmeg and 300 biscuits, plus a great cask of Malaga.” (Rae 3)

Over the century and a half following its inception,

“an astonishing number of variations surfaced. Sailors substituted new ingredients when they couldn’t obtain the old, and so punch was made with Madeira wine in the eastern Atlantic islands and with rum in the West Indies and North America.”

Curtis claims that punch recipes called for as few as three or as many as six ingredients” and then describes a 1694 recipe from Barbados with eight of them. In reality the number of elements that may compose a punch is nearly unlimited. (Curtis 116-17)

Not this Punch, but whatever.

The eccentric Dr. William Kitchiner offers a characteristically delightful description of the drink’s attributes, its pleasures and pitfalls, in Cassell’s Dictionary of Cookery some six decades earlier than Larousse:

“With regard to the salubrity of punch, when drunk in moderation, hot in winter, or cold, and even iced in summer, it affords a grateful beverage, admirably allaying thirst, promoting the secretions, and conveying animation to the spirits.”

So far, so good, but Dr. Kitchiner, an expert on optics, envisions a certain problem with punch:

“If, however, amid the hilarity excited by the tempting fragrance and luscious taste, which the balmy bowl seldom fails to inspire, it be too freely drunk, its powerful combination of spirit and acid, instead of proving favourable to the constitution, will infallibly tend to bring on the gout, even sooner than most wines or strong cider, unless happily prevented by using a considerable deal of exercise.”

Perhaps Soul Cycle and other fitness cults may start serving punch to entice more victims while urging discretion upon them:

“Punch, like all the prime blessings of life, is excellent and salutary when enjoyed at proper seasons. We must not charge on them our own want of discretion, by which alone they are ever converted to evils.” (quoted at Dejey 8)

2. Doctor’s orders.

In his idiosyncratic and informative Cook’s Oracle, first published in London during 1830, the ordinarily loquacious Dr. Kitchiner says little about punch, a lot less about its qualities than he explained for Cassell’s. Instead he gets right to the recipe preceded by a sort of time-saving if somewhat byzantine and time consuming short cut.

After describing his formula for “Lemonade in a Minute--(No. 477),” which incorporates citric acid, “quintessence of lemon peel (No. 408),” “clarified syrup (No. 475) or capillaire” (itself No. 476) or, another option, his own “superlative spirit of lemons” (No. 391; the doctor is not self-effacing). “If,” however, “you have none of No. 408, flavour your syrup with thin-cut lemon-peel, or use syrup of lemon-peel (No. 393).”

“Quintessence of lemon peel” (408) is a formula for bitters made with lemon oil and grain alcohol. “This elegant preparation, boasts the ‘doctor’” (Kitchiner was in this respect a fraud, not a medical man), “possesses all the delightful fragrance and flavour of the freshest lemon peel.” While the quintessence “will be found a superlative substitute for fresh lemon-peel for every purpose that it is used for,” both savory and sweet, liquid and solid, it is particularly convenient for punch:

“Obs. A few drops on the sugar you make your punch with will instantly impregnate it with as much flavour as the troublesome and tedious method of grating the rind, or rubbing the sugar on it.” (Oracle 274)

3. A note on three species of Negus.

The quintessence also would enhance your negus, a weak form of punch. In an uncharacteristic oversight given his habitual cross-hatching, Dr. Kitchiner does not offer a formula for the drink, according to dictionary.com “a hot drink of port, sugar, lemon, and spices… named for Colonel Francis Negus (died 1732), who created it.”

Perhaps. Negus served under Marlborough during the War of the Spanish Succession and gained favor with both George I and II. Most commentators hedge a bit by ‘attributing’ the drink to him, although in 1799 a correspondent of the Gentleman’s Magazine bolstered the claim by noting that the term first circulated in the colonel’s regiment.

By happy coincidence Negus also was a title of the Abyssinian Emperor and so C. A. M. Fennell, a nineteenth century lexicographer at Jesus College, Cambridge, apparently considers whoever coined the term for the drink clever and literate. He “makes the ingenious but improbable suggestion” in The Stanford Dictionary of Anglicised Words and Phrases “that the name may have a punning connection with the line in ‘Paradise Lost,’ xi. 397, ‘Th’ empire of Negus to his utmost port.’” (Fennell 569; Seccombe)

4. Back to the Oracular punchbowl.

To return to the recipes recorded by Dr. Kitchiner, syrup of Lemons combines (391) lemon juice and peel with sugar, cooked, skimmed, strained and cooled, while as its name infers the syrup of lemon peel (393) omits the juice to use water instead. It also may be made with orange peel. (Oracle 267, 263)

The addition of beaten egg white to simple syrup during the cooking process creates the clarified syrup (475, which “will keep for months, and is an elegant article on the sideboard for sweetening;” the addition of “Curacoa” (“No. 474”) to the clarified syrup creates the capillaire (476). (Oracle 297)

Curacoa in turn is essentially a liqueur. It has a base of clarified syrup and grain alcohol with the flavor of dried and powdered Seville orange peel “or, which is still better, of the fresh peel of a fresh shaddock.” (Oracle 296) The shaddock, named for an apocryphal captain who by legend introduced the tree to Barbados, is a sour citrus fruit also called the pomelo or pummelo, so sour that crossed with sweet orange it becomes grapefruit. (Petruzzello; Kumamoto et al. 97)

Once you have selected your quintessence, your syrup or syrups or capillaire to make the lemonade, “the addition of rum or brandy will convert this into: Punch directly--(No. 478).” (Oracle 297-98) In what appears to be a redundant descriptive explanatory specification for “Shrub, or Essence of Punch--(No. 479),” he goes on to disclose: “Brandy or rum, flavoured with No. 477, will give you very good extempore ‘essence of punch.’”

Although his instruction is not entirely clear, Dr. Kitchiner appears to mix his punch in the proportion of about a part and a half of water to a part of brandy. For each pint of brandy, he recommends a pint each of spring water and clarified syrup without mentioning his system of alternative chutes and ladders. The clarified syrup itself suspends a whopping two pounds of sugar (“a quarter pound more than that directed in the Pharmacopoeia of the London College of Physicians”) in a pint of water so a pint of the syrup will include a lot less water than the pint of it that goes into the formula. (Oracle 297)

Dr. Kitchiner’s research reveals that the essence, or shrub, itself is a versatile liquid for the larder, especially for making a quick punch, as another ‘Obs.’ indicates.

“The addition of a quart of Sherry or Madeira makes ‘punch royal;’ if, instead of wine, the above quantity of water is added, it will make ‘punch for chambermaids,’ according to SALMON’S Cookery, 8vo. London, 1710.” (Oracle 298)

5. A detour farther back.

The reference is to the fourth edition (with “above Eleven Hundred Additions”) of William Salmon’s Family Dictionary: or, Household Companion. It first had appeared in 1696. The citation indicates that the ‘doctor’ was undeterred by historical controversy, for Salmon was a contentious figure even by the standard of his contentious time. A contemporary was not alone in attacking him as “a scoundrel… of infamous character…. ” (Hanson 118)

By the time he published the first of his many books, Salmon had been “busy building a career upon his own invented credentials” including an MD degree he had not earned, and lied even to the extent of promoting “a familial connection” with prominent surgeons who shared his surname “where in all likelihood there was none.” (Hanson 108)

A prominent pugilist in the conflict between conventional physicians and proponents like him of ‘proprietary medicine,’ Salmon harbored no fear of controversy or litigation. Among the medicines Salmon sold were his ‘Elixer,’ cold and cough lozenges, Family Pills and Family Powder along with “a variety of other cures, recipes and pills, and jealously protected his trade names.” Along the way he became wealthy.

His remedies competed with those peddled by established doctors licensed by the Royal College of Physicians, which therefore serially prosecuted Salmon for fraudulent and unauthorized marketing and sales. He in turn assailed “the Pride, Covetousness and Idleness of the Physicians” for trying “to Monopolize all the practice of Physick” and united the apothecaries and other makers of proprietary medicines challenging the attempts of the College to control all dispensing of remedies. (Monod 129)

Salmon, as the cookbook cited by Dr. Kitchiner indicates, did not confine his endeavors to the manufacture of patent medicines. He was a prolific author whose various books “provided for his English readers a compendium of everything.” (Hanson 109) His bestselling effort, Polygraphice, the Art of Drawing, Engraving, Etching Limning, Painting, Washing, Varnishing, and Dying, in fact ranges over even more subjects including cosmetics and perfumery, while its various editions grew from three ‘books’ and some three hundred pages to eleven ‘books’ and 939 pages. It “remained throughout its publishing history an odd collection of disjointed material dominated by practical instruction and recipes.” (Hanson 111, 113)

A prominent art historian further describes Polygraphice as “an encyclopaedic tour de force of piracy… little more than wholesale thievery.” (Talley 189-90) The description explains how Salmon managed to be so polymathic and prolific; it also fits just about everything else Salmon published.

His subjects included alchemy, anatomy, astrology, botany, chiromancy, disease treatments and pharmacology in addition to the myriad artistic media and beauty secrets covered in Polygraphice along with the cookery of his Family Dictionary, while he also “seems to have had a role in the most influential sexual primer of the early modern period, Aristotle’s Master-Piece” which predictably enough had no connection to Aristotle. (Hanson 110)

6. No rush to judgment.

Hanson for one refuses to condemn or dismiss Salmon outright. Plagiarism was hardly uncommon during the period, and as Hanson asserts, “the lines between physician and quack should be drawn lightly, in pencil rather than pen,” during the early modern era. He also observes that “as for efficacy, one was as likely to recover in the care of an irregular practitioner as under the scrutiny of an overzealous doctor set on bleeding and purging.” (Hanson 110)

An impostor Salmon may have been, but he was an accomplished one whose publications made him “a household name” and found their way onto the shelves of William Congreve, Daniel Defoe, Dr. Johnson, Isaac Newton, Horace Walpole and other intellectual titans. His work proved popular farther down the social scale as well, and “suggests the degree to which expansive curiosity was not limited to the virtuosic elite but pervaded English culture.” (Hanson 121, 119, 116)

Paul Monod concurs with the appraisal of Hanson that Salmon served a function and fulfilled a need: “The simple, didactic tone of his writing suggests that he was addressing himself to people who wanted straightforward information on practical subjects,” not to mention, he might have added, titillating ones like sex. (Monod 107)

Salmon was so influential that as late as 1835 his publications were “still sought by some practitioners and the public in the Country” if not necessarily any longer in London. (Fosbroke 599)

7. Another confounding character.

In that year John Fosbroke, a regular contributor to The Lancet and himself a medical researcher, included a profile of Salmon in the journal under the unlikely but perversely enchanting title “On the Effects of the Ethereal Tincture of Male Fern Buds, the French Holly, Iodine, and Bear’s Foot, in Cases of Worms of the Intestine.” It is unclear why Salmon appears in the telling, but he does, along with Nicholas Culpeper, the great seventeenth century herbalist, astrologer and physician.

Fosbroke makes an assessment of the men so ambiguous it verges on incomprehensible. “In these days of medical reform,” he digresses from his putative subject of intestinal worms,

“I cannot pass over two sturdy old reformers like Salmon and Culpeper…. They were as much wonders of industry and usefulness, as they were conspicuous objects of collegiate obloquy and oppression.”

Despite some prescient insights of his own--Salmon was among the first to recognize dementia, for example, observing that a sufferer was “not mad, or distracted like a man in Bedlam” but “decayed in his wits--” it is hard to consider Salmon so much a principled reformer as an opportunistic huckster. (Mahendra at Springer 21)

Fosbroke goes on to claim with some repetition that as a “professor of ‘extraordinary cures’” Salmon “had to endure the obloquy which attaches to irregularity” but then appears to equate that irregularity with exploitation. At a time when

“the country was full of medical quackery and imposture…. Salmon, no doubt, adopted the particular system of the day…. He endeavored to work upon the superstitious as well as the religious prepossessions of patients, by mixing horoscopes with the prayers and prescriptions, and to inspire a feeling of reverence by surrounding himself with the mummies, tortoises, scaly alligators, sharks’ heads, flying fish, musty drugs, dried bladders, and drawn teeth…. ”

Then, in a classic crack of the whip, Fosbroke endorses this

“immortal principle of delusion in the highest and lowest classes of society, which have given place to other methods of quackery and hypocrisy, different in form, but equally successful in practice.” (Fosbroke 599)

Unless, that is, the voice is ironic; perhaps the ‘equal success in practice’ was no success at all. Then again, Fosbroke is openly sympathetic to Salmon, so his conclusion remains inscrutable.

8. A different manifestation of the medical man.

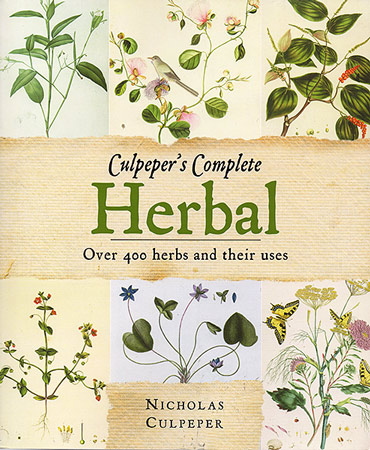

For some incomprehensible reason, Fosbroke likes the legacy of Culpeper a lot less than Salmon’s. “Nicholas Culpeper,” he intones, “was certainly inferior in science and learning to Salmon, but” for some reason incomprehensible to Fosbroke, no champion of the proletariat, “his ‘Herbal’ is always to be found with ‘Robinson Crusoe’ and ‘Pilgrim’s Progress’ in the houses of the vulgar, and of some of the higher sort of people.” (Fosbroke 599)

If Salmon was a bit of a scoundrel, however, Culpeper emphatically was not. A man of moral principle, early in the civil war he enlisted as a surgeon in the New Model and took a ball to the chest at first Newberry. The wound never healed, would continue to cause pain; complications would kill him at the age of only thirty eight.

Despite the suffering, a contemporary described his “small dark eyes, full of spirit,” while friends noted his “knack of jesting,” “consumption of the purse” and “outbursts of choler.” The reference to choler is to Galen, who considered it one of the four physiological humours, the one that made a person “quick-witted, no way shame-fac’d, furious, hasty, quarrelsome, fraudulent, eloquent, courageous, stout hearted.” Culpeper, according to George Scialabba, “seems to have been a merry, saucy rogue.”

“This is,” Scialabba wryly continues, “unmistakenly the profile of an anti-authoritarian.” (Scialabba) “Throughout all Culpeper’s writings,” as F. N. L. Poynter points out,

“there is a genuine and passionate concern for the sick poor. Much of the heat with which he expressed his views of the College of Physicians was engendered by this concern and the fact that the College, a very small and exclusive body, exercised a monopoly. It was a time when all privilege and power was put in question and to Culpeper, whose reforming zeal extended to politics and religion as well as to medicine, it seemed that this monopoly put medical treatment beyond the reach of the poor.” (Poynter 156-57)

Culpeper insisted that “no man deserved to starve to pay an insulting, insolent physician.” (Complete Herbal, “Introduction”)

Quick, take her to Culpeper.

Culpeper practiced medicine in East London, where he treated patients, as many as forty a morning, the impoverished for free. (Poynter 154, 156) His generosity in turn impoverished him despite marriage to a woman from a wealthy family, although some of the problem arose from his own profligacy.

Unlike most contemporary doctors, Culpeper actually examined his patients rather than simply sniffing their urine. He is said to have stated that “as much piss as the Thames might hold” could not provide the diagnosis for anything. As a contemporary commented with less pith, Culpeper refused “to put confidence in the single testimony of the Water, which as he used to say, ‘drawn from the Urine, is as brittle as the Urinal’…. ” (Complete Herbal, “Introduction;” Poynter 156)

Culpeper rebuked his more orthodox competitors for their distance not just from the bodies of their patients. “This,” he wrote in reference to their theoretical rigidity,

“not being pleasing, and less profitable to me, I consulted with my two brothers, DR. REASON and DR. EXPERIENCE, and took a voyage to visit my mother NATURE, by whose advice, together with the help of DR. DILIGENCE, I at last obtained my desire; and, being warned by MR. HONESTY, a stranger in our days, to publish it to the world, I have done it.” (Culpeper, “Introduction”)

The publication at issue was his Complete Herbal, an exhaustive survey of virtually all useful plants found in Britain. The work did more than any other to assist laypeople in choosing esculents not only for the medicine chest but also for the pot.

Beginning with the sixteenth century pottage, a cereal based preparation at the intersection of soup and stew, pottage would become a universal staple eaten by all strata of English society. No ingredients were more characteristic of the preparation than herbs, and they came to proliferate in English gardens in no small measure thanks to Culpeper. (Perkins 44, 45)

Culpeper engaged in unauthorized conduct in common with Salmon but unlike him was open about his artifice. Culpeper considered the ambition of the medical colleges to control prescription and treatment no less repugnant than Salmon, but for an eleemosynary rather than venal reason.

Culpeper broke the monopoly of the colleges in part by illicitly translating medical and pharmaceutical texts from the Latin, German and Italian into English. This at a time when “merely translating the classics (or, as William Tyndale found, the Bible),” let alone practical proprietary manuals, “into the vernacular was considered subversive.” (Scialabba)

For his efforts the colleges castigated Culpeper as a quack, but in contrast to Salmon the epithet did not apply to him. “If,” as Poynter concludes, “our concern is the history of medicine as it was professed and practised, then Culpeper is a figure of outstanding importance” based in no small measure on his practicality and compassion. (Poynter 153)

The Herbal that Fosbroke disdains was the most popular of Culpeper’s many popular publications, most of which his wife shepherded to print following his untimely death. Salmon is forgotten now outside the academy while Culpeper’s Herbal still may be found in enlightened libraries along with Bunyan and Defoe. It has remained in print since the first, 1651, edition. The verdict of history is more than fair.

9. Back in the kitchen, or kitchens….

Unlike some cookbooks of the time, which present their recipes in a heap of inconsistent, even arbitrary categories, Salmon’s Family Dictionary is remarkably modern in format. Whatever their sources, as its title implies the book is an alphabetical listing of succinct recipes even to the extent that the entry “PUNCH ORTHODOX, or ROYAL” follows in precise alphabetical order the less common “PUNCH for CHAMBERMAIDS.”

Incidentally Dr. Kitchiner’s reading of the two references is wrong. No fortified wine appears in the formula Salmon appropriated for the brandy based ‘Punch Royal,’ while white wine, absent from the Kitchiner description, does appear in the Dictionary version of ‘Punch for Chambermaids.’ (Salmon entries 215, 216)

10. Pirates and cows and perfection, Oh My!

At The Eddy in Providence, Rhode Island, where they fashion a formidably good Thai devilled egg, the proprietor’s wife makes a different punch each week because, as the cocktail card explains, “It’s what pirates drink! Everybody likes pirates!” Now once again New Englanders drink it as well. The price is gentle, the punch strong and the flavor always fresh.

The East End, nearby on flourishing Wickenden Street, goes an elaborate step further. They are making milk punch, not a murky drink but rather a limpid one using an extract minus the whitening curd. Their punch also varies each week; all of them with the milk base, all of them good.

Milk punch may be built on a base of very nearly any spirit or combination of spirits and all forms of citrus, along with any number of fortified wines and flavorings. A recent recipe at the East End combines Bourbon with an apparently unappealing partner, cherry heering, but in fact the punch is extremely good. Another pairs the Bourbon with banana; a third incorporates mezcal. They all are silken, almost gelatinous in the manner of a proper milk punch and none of them is oversweet.

In his breezy and, he happily admits, anecdotal rather than analytical history, Punch: The Delights (and Dangers) of the Flowing Bowl, David Wondrich devotes but a handful of pages and describes but a single formula for milk punch. His rationale relegates all the current experimentation to irrelevance:

“Milk punch was no sooner invented than perfected.” (Wondrich 166)

11. Milk the emollient.

What Wondrich does have on milk punch is good, and addresses the acidulous aspect identified by Dr. Kitchiner that plagues drinkers of too much other punch. “If,” Wondrich recounts, “there was one complaint Punch [sic] elicited from its habitual consumers, it was that it was rather acid on the stomach” due to its habitually high citrus content.

Punchmakers experimented with a number of emollients, including additional sugar (cloying), Sauterne or something similar and porter (each ineffective for the purpose to hand but all otherwise possessed of considerable charms).

“The very best solution,” Wondrich thinks,

“was discovered very early indeed in Punch’s history: milk. When added to punch, it curdles pretty much immediately, making a disgusting mess that when strained out leaves a Punch that is not only clear but also exceptionally smooth and creamy-tasting without actually being creamy.” (Wondrich 164-65)

Too often the ahistorical among us assume that twenty first century people are smarter than their forebears. George Kurpinsky, a San Diego bartender and convert to milk punch admits he was skeptical about the clarification process. Kurpinsky initially assumed it must be “a modern technique,” “centrifugal clarification with chemical components.” “I don’t,” he admits, ordinarily “think about somebody boiling milk and introducing it to acid” but some historical research convinced him otherwise. (Strickland)

As Dan Sousa explains, the whey protein that remains a component of milk punch provides the body that imparts its velveteen texture. The curd strained away from the punch takes with it the volatile compounds from the citrus and the impurities from the booze, which stabilizes the drink to preserve it--the shelf life of milk punch is nearly indefinite--and eliminates the bronzed color of the arrack, brandy, Bourbon, Port, rum or other base alcohol to impart the palest hue to the punch. (Swift)

If Salmon had known the properties of milk punch the acquaintance might explain his fascination with alchemy.

12. A perfect punch?

In any event the perfect milk punch is, according to Wondrich, “the oldest extant recipe.” It dates to a 1711 kitchen manuscript compiled by Mary Rockett, one of the many great women in the history of British foodways, although sadly enough nobody has written much of anything about her. The recipe in full is easy enough to read but requires precision and patience to perfect. “To Make Milk Punch,” she begins,

“Infuse the rinds of 8 Lemmons in a Gallon of Brandy 48 hours then add 5 Quarts of Water and 2 Pounds of Loaf Sugar then Squize the juices of all the lemons to these Ingredients add 2 Quarts of new milk Scald hot stirring the whole til it crudles [sic] grate in 2 Nutmegs let the whole infuse 1 Hour then refine through a flannel Bag.” (quoted by Wondrich at 167)

13. The calf’s foot question.

It is a shame that Wondrich has so little truck with milk punch preferring, as he does, punches that are, literally, gelatinous. ‘Oxford punches’ add calf’s foot jelly as their element of base, but in terms of milk punch Wondrich does note that the addition of jelly would gild the proverbial lily. As he concedes in quoting an 1827 commentator, “the milk will sufficiently temper the acrimony of the lemon juice.” (quoted by Wondrich at 168) The jelly punch, probably for purposes of marketing never named that way, is a lot more laborious to build and may not appeal to our readers as much as the punch made silken instead of wobbly by milk.

14. An even more ingenious doctor dabbles in punch.

Wonderful figures in addition to Mrs. Rockett have made immortal contributions to the literature of milk punch, Benjamin Franklin first among them.

Franklin, who along with his friend David Hume seems to have done everything and written to everyone involved with the British Enlightenment, sent his own receipt for milk punch to James Bowdoin in Roxbury just west of Boston. The two corresponded for four decades to share their scientific and evidently bibulous interests. (MHS)

After what has become the obligatory adolescent attempt to endure a vegetarian regimen, Franklin (ahead of his time in so many things) became a lifelong devotee of good drink and dishes, predominantly British ones. No Jeffersonian Francomania, not in terms of cuisine anyway, for Franklin. His preference for English foodways was sufficiently strong to induce him to translate into French a number of recipes from the bestselling Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy by Hannah Glasse for use by his presumably perplexed Paris cook. (Chinard 35)

Franklin’s receipt for milk punch is not much changed from the Rockett prototype. In common with her, he apparently liked to keep a lot of it on hand. That is more than feasible, because he shelf life of milk punch verges on immortality.

Franklin’s succinct script specifying brandy and citrus produces a lot more than a gallon. This is it:

“To make Milk Punch Take 6 quarts of Brandy, and the Rinds of 44 Lemons pared very thin; Steep the Rinds in the Brandy 24 hours; then strain it off. Put to it 4 Quarts of Water, 4 large Nutmegs grated, 2 quarts of Lemon Juice, 2 pounds of double refined sugar. When the Sugar is dissolv’d, boil 3 Quarts of Milk and put to the rest hot as you take it off the Fire, and stir it about. Let it stand 2 Hours, then run it thro’ a Jelly-bag till it is clear; then bottle it off.---” (MHS)

In common with Dr. Kitchiner, Franklin created a formula for shrub to be drunk straight or as a handy base for making milk punch faster than from scratch. His instructions are unique in their modernity. “‘Orange shrub,’” observes Gilbert Chinard, speaking of the eighteenth century,

“is found in many English cook books but nowhere with the exact formula and scientific directions which seem to have been written by a scientist trained in laboratory methods.” (Chinard 36)

The same may be said of Franklin’s precise program for producing milk punch.

15. A long goodbye.

Milk punch survived, barely and in isolated spaces, into the first half of the nineteenth century but for the most part it had until recently been an artifact largely of the sixteen and seventeen hundreds. Eliza Acton offers no formula; neither does the redoubtable Christian Isobel Johnstone, although as Meg Dods she records good recipes for brandy, currant and rum shrubs in her irresistible Cook and Housewife’s Manual.

The first edition of Mrs. Beeton, from 1861, gives the punch barely a line, and that in the microprint reserved for inconsequential entries, in all of its 1,112 pages. The guidance is gaunt:

“‘Milk punch’ may be extemporized by adding a little hot milk to lemonade, and then straining it through a jelly-bag.” (Beeton 892)

The reader is left to guess at proportions and infer that she should add an unidentified form of alcohol to the unspiced imposter.

Another, spectacularly superior, outlier occurred a year later. In How to Mix Drinks, the legendary New York bartender Jerry Thomas outlines a sophisticated “English Milk Punch” spiced with cinnamon, clove and coriander. Pineapple accompanies the usual citrus in the form of lemon for the acid component and the punch incorporates arrack and brandy along with rum. A jolt of green tea fights any fatigue that may befall the flagging reveler.

In common with Wondrich, but in livelier terms, Thomas comments on the insalubrious appearance of the steeping punch. It is important to

“let it stand for an hour, but do not suffer any one of delicate appetite to see the mélange in its present state, as the sight might create a distaste for the punch when perfected.” (Thomas 21)

A flicker of milk punch flared, for a short time, in a most likely location a century before the current cocktail craze. New Orleans always has revered traditional food and drink, and for a short time until a short time ago Paul Gustings brewed the Thomas milk punch at Broussard’s.

Gustings was a revivalist rather than innovator, and, also in the manner of Creole foodways, proud of his adherence to the past. “Do I ever change it up?” he asked back in 2016:

“Nope. I leave it alone. It’s been around that long, why mess with it? If I wanted to do something completely different, I’d do something completely different and not call it English Milk Punch.” (“Broussard’s”)

Notwithstanding the perfection of milk punch, High Victorians for the most part did with it what they foolishly did with most cultural manifestations of the long eighteenth century and its Enlightenment ideals, whether its elegant classical architecture, its intellectually secular cast, its nascent feminism, its sexual license or its traditional British foodways. By 1875 Cassell’s Dictionary of Cookery, which includes hundreds of recipes for punch and its cousins capillaire, posset, sangaree, shrub and syllabub, would identify only two milk punches. “This beverage,” Cassell’s reports, “is not much used nowadays.” (Dejey 74)

Their loss; now, our gain.

Punch formulae appear in the practical.

Sources:

Anon., “Benjamin Franklin’s milk punch recipe,” MHS Collections Online, http://www.masshist.org/database/viewer.php?old=1&item_id=294 (n.d.; accessed 30 April 2019)

Anon., “Broussard’s English Milk Punch,” Louisiana Cookin,’ http://www.louisianacookin.com/broussards-english-milk-punch/ (22 November 2016; accessed 30 April 2019)

Anon., www.dictionary.com/negus (n.d.; accessed 14 May 2019)

Isabella Beeton, The Book of Household Management (orig. publ. London 1861; facsimile London 1982)

Gilbert Chinard, Benjamin Franklin on the Art of Eating (Princeton 1958)

Nicholas Culpeper, The Complete Herbal (OKA The English Physitian) (London 1835; orig. publ. 1653)

Patrick Curry, “Culpeper, Nicholas (1616-1654),” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford 2004)

Wayne Curtis, and a Bottle of Rum: A History of the World in Ten Cocktails (New York 2007)

Marie Dejey (ed.), Victorian Cups And Punches and other concoctions (London 1974)

Rae Katherine Eighmey, Stirring the Pot with Benjamin Franklin (Washington, DC, 2018)

C. A. M. Fennell (ed.), The Stanford Dictionary of Anglicised Words and Phrases (Cambridge 1892)

John Fosbroke, “On the Effects of the Ethereal Tincture of Male Fern Buds, the French Holly, Iodine, and Bear’s Foot, in Cases of Worms in the Intestine” The Lancet vol. 24 no. 623 (London 1835) 597-601

Craig Hanson, The English Virtuoso: art, medicine and antiquarianism in the Age of Enlightenment (Chicago 2009)

William Kitchiner, The Cook’s Oracle and Home Keeper’s Manual (London 1830)

J. Kumamoto, R. W. Scora, H. W. Lawton & W. A. Clerx, “Mystery of the forbidden fruit: Historical epilogue on the origin of the grapefruit,” Economic Botany Vol. 41, Issue 1 (January 1987) 97-107

Paul K. Monod, Solomon’s Secret Arts: The Occult in the Age of Enlightenment (New Haven 2013)

Blake Perkins, “An Enquiry into the Derivation of Chowder,” Petits Propos Culinaires 109 (September 2017) 32-67

Melissa Petruzzello, “Pummelo Plant and Fruit,” https://www.britannica.com/plant/shaddock (n.d.; accessed 14 May 2019)

F. N. L. Poynter, “Nicholas Culpeper and his Books,” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences Vol. 17 No. 1 (January 1962) 152-67

Simon Rae (ed.), The Faber Book of Drink, Drinkers and Drinking (London 1991)

William Salmon, The Family Dictionary: or, Household Companion (4th edition London 1710)

Thomas Seccombe, “Negus, Francis,” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography vol. 40 (Oxford 1894), https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Negus_Francis_(DNB00) (accessed 14 May 2019)

Cara Strickland, “The Many modern Faces of Milk Punch,” Tales of the Cocktail, https://talesofthecocktail.com/history/many-modern-faces-milk-punch (1 December 2016; accessed 30 April 2019)

Sally Swift, “Classic cocktail revived: America’s Test Kitchen on milk punch, The Splendid Table, http://splendidtable.org/story/classic-cocktail-revived-americas-test-kitchen-on-milk-punch (15 September 2017; accessed 16 May 2019)

Jerry Thomas, How to Mix Drinks Or The Bon-Vivant’s Companion (New York 1862)

David Wondrich, Punch: The Delights (and Dangers) of the Flowing Bowl (New York 2010)