A flight, at intervals unfortunately of fancy, through the development of American foodways through the examination of some influential figures via Women in the Kitchen by Anne Willan and featuring a pirate of exquisite mind as well as soy sauce.

The late, great David Underdown, historian of early modern England, its civil war and Protectorate, liked to tell his students he was saving biography as a historical genre for his old age, not because biography is a lesser field but because it is more manageable. Instead however he decided to forgo the format and focus on the history of cricket.

Anne Willan, who by now has written or contributed to some seventy volumes on food, has followed Underdown’s initial impetus with Women in the Kitchen, a nearly Namierite collective biography of twelve people who exerted an outsized influence in the kitchen and on the page. The effort has attracted high praise. Heller McAlpin in The Wall Street Journal, for example, considers Women “an edifying survey.” (McAlpin)

Nonetheless Women could be construed by the caustic as an exercise in trading on the zeitgeist that celebrates anything other than the male and white but it is in fact anything but that. Eleven of the profiles arise out of the Anglosphere where women historically have played an outsized role in fashioning foodways compared to any other culture. It would be difficult to fault any of Willan’s subjects: All of them have written cookbooks of widespread and lasting influence.

Willan, an English authority on a number of cuisines, has geared this book to the American market; its stated intent is to trace the impact of these twelve (or, perhaps, in reality eleven) women on the development of American foodways.

MIA Elizabeth David

MIA Elizabeth David

That explains the otherwise inexplicable exclusion of Elizabeth David, widely considered the most influential English culinary author of the twentieth century, but does not account for the exclusion of Eliza Acton, who not only took her turn as bestselling cookbook author on the North American market but whose Modern Cookery for Private Families also influenced all who came after. For her part, David considers Acton the greatest British cookbook author of all time.

Equally inexplicable is the exclusion of Isabella Beeton. Whatever her perceived shortcomings today, and despite the fact that she probably could not cook and certainly drew ‘her’ recipes from submissions she solicited, the influence of her Book of Household Management was immense on both sides of the Atlantic for a century following its first publication in 1861.

Miss Acton and Mrs. Beeton were not the only English authors with outsized influence over American culinary history. Willan has included three of them in her pantheon.

2. Getting to know an early master of the kitchen, or, ‘As the World Turns.’

Despite their brevity, some of these uneven sketches manage to convey not only the style of each author’s cooking but also the cast of her personality. Each of the better essays is nothing more than Willan’s affectionate meditation on a woman and her legacy, and for many of her readers nothing more is needed.

Willan notes for example that Hannah Glasse’s “background story reads like one of the romantic novels so popular in her time,” and so it does. Born illegitimate to a rich country gentleman, she nonetheless grew up in his household without familial stigma, although one occasionally reliable writer maintains that Glasse considered her mother a “wicked wretch.” (Willan 31; Dickson Wright 3662))

At the age of sixteen her father sent Glasse to live in London with his mother, who forbade her from all social activities. An insouciant Glasse evaded the ban, to elope promptly with a thirty year old Irish widower languishing on the half pay of a subaltern in the British army, according to Wilan “a feckless though presumably charming character.”

She would bear him ten or eleven children depending on the source; five of them survived infancy but one of those died at sea serving with the Royal Navy off Pondicherry. (Willan 31, 32, 35; Robb-Smith) Glasse would appear to have been a doting mother. Notwithstanding the Jeffersonian scale of financial overstretch in the Glasse household she paid to educate her daughters at actual schools (no unqualified tutors; a rarity in her time) and sent her sons to Eton and Westminster.

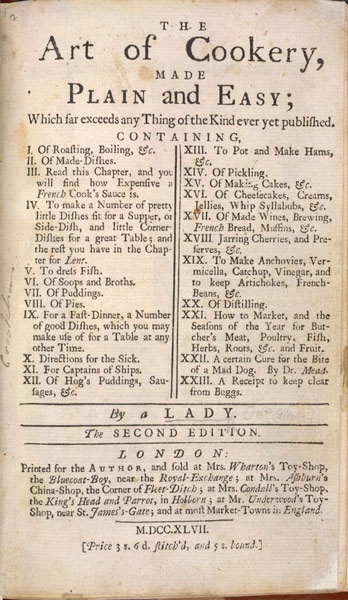

In common with a number of these authors, Mrs. Glasse turned to writing later in life--she was thirty nine when The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy, her first and bestselling book, appeared--out of stark economic necessity. Previous attempts to supplement her husband’s meagre income included an unrealized scheme to market a patent medicine that, in other hands, would achieve success under the unintentionally ironic name “Daffy’s elixir.” (Willan 32)

Mrs. Glasse is an indispensable figure for any book, like Women in the Kitchen, that attempts to chart the most influential cookbook authors. The Art of Cookery first appeared in 1747. In that same year her husband died and with a daughter Mrs. Glasse opened a dressmaking business prestigious enough to attract the patronage of the Princess of Wales. Despite its popularity at court the business apparently failed to turn a profit.

By 1757 debts of some £10,000 (over £2 million today) had landed Mrs. Glasse in debtors’ prison. Forced to sell her rights in The Art of Cookery, she got out of stir by the end of the year and immediately attracted investors for a new venture, The Servant’s Directory. It would appear, probably during 1760 (the sole edition is undated) followed by The Compleat Confectioner the same year. Neither book was particularly popular; both relied on extensive plagiarism, perhaps a cause of their failure as well as an indication of her urgent need for cash. Unfortunately Willan omits a lot of this rollicking road from her profile.

3.An encapsulation of English cuisine.

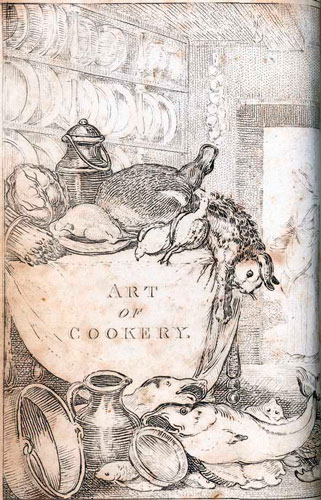

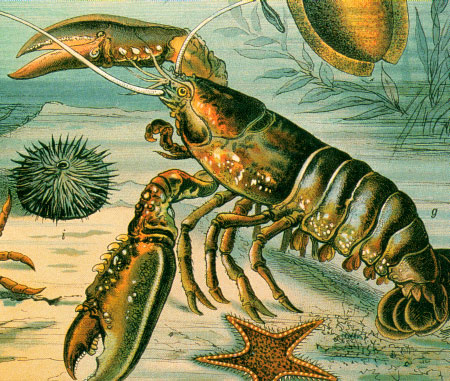

Notwithstanding its late start The Art of Cookery would, other than the bible and some volumes of pornography, become the bestselling book of the century on any subject in any language. Willan’s selection of recipes from the bestseller is inspired, and undercuts the conventional wisdom that traditional English food is bland. Three of the four would make an ideal English dinner.

Mrs. Glasse potted salmon seasoned high with allspice, clove, the mace essential to so many eighteenth century English dishes and pepper. Willan provides but a partial explanation of potting, a technique that will be unfamiliar to most American readers:

“‘Potting’ is an English term for preserving meats and fish [Willan might have added cheese] by thoroughly cooking them in fat, then sealing them so no air can penetrate. Butter must first be clarified to remove whey and other impurities.” (Willan 44)

To clarify the reference to clarification, potted foods are both cooked in and sealed with the clarified butter.

Willan also selects an extremely good recipe for boiled turkey from The Art of Cookery. Cooks in both Britain and North America boiled their turkeys a lot more often than they roasted them. For good reason; the boiled bird will not dry out like a roasted bird and the texture of the meat becomes silken.

Mrs. Glasse bathes her boiled turkey with a traditional celery sauce but the preparation takes a lot longer than other recipes because she reduces the stock after cooking the bird to make a sauce of irresistible intensity. In common with other recipes for boiled turkey, or chicken or duck for that matter, the recipe is simple, foolproof really, notwithstanding the longer cooking time. (Willan 46)

The last of the three, from The Compleat Confectioner, is a stunning ‘cream,’ or potted pudding, made with the darkest chocolate enriched with cream and laced with lemon, rosemary and sweet wine. The recipe was, as Willan notes, one of the first to use chocolate in a dish rather as a drink. (Willan 49)

4. An echo of Jane Austen.

Maria Eliza Rundell was very nearly as influential in her time as Mrs. Glasse in hers. A New System of Domestic Cookery first reached print during 1806 and would bump the Glasse book from the top of the American charts in terms both of sales and influence.

With some skill, Willan sketches the social and cultural setting in which Mrs. Rundell lived:

“Mrs. Rundell was writing in exactly the same decade as Jane Austen, so the descriptions of Bath in Persuasion would accurately evoke the lives of the Rundells, who spent a year or two in Swansea, the fashionable seaside town where Maria wrote A New System of Domestic Cookery.” (Willan 76)

Willan also evokes the principled, forceful personality of Mrs. Rundell herself. She did not turn to writing until the age of 61 after she had developed a close friendship with John Murray, an influential publisher whose authors included Austen herself, Byron and Washington Irving. (Willan 79, 76)

Mrs. Rundell stood up for herself. Despite their friendship she would fall out with Murray and sued him for neglecting to promote the New System in a case that took two years to settle for the equivalent of what is currently about $100,000. (Willan 79-80)

Not that Mrs. Rundell was grasping or unkind; she believed that cooks “such as are honest, frugal, and attentive to their duties, should be liberally rewarded.”

Frontispiece to the New System

Willan also describes an almost twenty first century sensibility. Mrs. Rundell, she explains,

“speaks of ingredients and their treatment in the kitchen with respect, almost affection. She must have been an excellent boss and she must surely have enjoyed her dinner as much as she did describing how to cook it.” (Willan 81)

The New System itself also appears remarkably modern. Willan refers to its “easy, readable style,” its “fluency and accurate punctuation;” not, however, two notions necessarily linked. The presence of Mrs. Rundell is calm, even ressuring; Willan properly notes her air of “competent authority.” (Willan 76, 75)

Willan cites some lovely asides from The New System: “…. Mrs. Rundell abhorred waste,” a useful prejudice amid the shortages and high prices of the Napoleonic Wars: “Rolls, muffins, or any sort of bread, may be made to taste new when two or three days old, by dipping it uncut in water, and baking afresh or toasting.” (Willan 78)

Willan properly emphasizes the continuities that characterize English cuisine. “Mrs. Rundell describes,” for example, “how to create Jelly to cover cold Fish,” flavoring it with “lemonpeel, white peppers, a stick of horseradish, and a little ham or gammon. She clarifies it with egg whites and strains it through a jelly bag to be sparkling clear, just as we do today.” (Willan 77)

In unselfconscious, conversational style Willan offers welcome evidence, via Mrs. Rundell, that traditional English food was highly seasoned.

“A well-run kitchen relied on seasonings developed by the cook such as Kitchen Pepper (a finely powdered mix of ginger, cinnamon, black pepper, nutmeg, allspice, cloves and salt), portable soup (similar to today’s meat glaze often given to [sic] its French name of demi-glace), and a variety of ketchups starting with mushroom and including a type of fish sauce. Rather to my surprise Mrs. Rundell uses soy sauce, brought in from Asia, as a flavoring.” (Willan 78)

5. An unlikely note on the history of soy sauce in England and North America while celebrating ‘a pirate of exquisite mind.’

She should not have been surprised. In 1679 Locke wrote that ‘saio,’ or soy, sauce was being imported to England from the East Indies. He is no outlier. John Chamberlayne noted in 1682 that “you London Gentlemen… value… your Soys.” (Shurtleff 7)

William Dampier encountered soy sauce in what is now Vietnam during the portentous year of 1688. He explained that “the true Soy comes” from Japan where “it is made only with Wheat, and a sort of Beans mixt with Water and Salt.” Dampier added that the Europeans he encountered there held soy sauce in great esteem. It was the first English appearance of the precise term in print and would become the standard usage. (Shurtleff 64, 70-71)

Dampier is a fascinating if forgotten figure, remembered principally for a pejorative comment about native Australians wrenched from context. He later recanted the comment in some detail with “a far more favorable analysis” after becoming intimately acquainted with them. (Fater)

William Dampier

Pirate and polymath, Dampier enjoyed outsize influence in his time before dying in impoverished obscurity. He was, as Rebecca Rupp describes him, not only a buccaneer but also “a dedicated naturalist, prolific author, astute hydrographer, world traveler” and more, including “groundbreaking observations on previously unresearched subjects in meteorology, maritime navigation, and zoology.” (Rupp; Fater)

After amassing capital as a pirate of the Caribbean during his twenties--the Scottish Dampier had been orphaned in his teens--he became the first person to circumnavigate the globe three times. He reached Australia some eighty years before James Cook and his rescue of a marooned castaway from an offshore island inspired Defoe to create Robinson Crusoe. (Rupp)

He described his encounter with soy sauce in A New Voyage Around the World, which appeared in print nine years after his sojourn in Vietnam. (Shurtleff 71) Based closely on his objective journals, he had written the book while imprisoned in Spain during 1694. it was the first adventure novel and “became an international bestseller, skyrocketing Dampier to wealth and fame.” His book created the market for travel writing, motivated Swift to write Gulliver’s Travels and was the template for Treasure Island.

As with Smollett, in his fiction Dampier describes the world he saw with such accuracy that historians, even scientists, cite it with confidence; Darwin for one considered A New Voyage a “mine of information.” (Perkins 53-54; Fater) His work more generally influenced Cook, Admiral Lord Nelson and Alexander von Humboldt among many others.

Dampier’s boundless curiosity included a fascination with the many foods he encountered for the first time. He was willing to eat anything and, as Rupp notes, “[p]ortions of his journals read like cookbooks.” His description of the process for making what eventually would be called guacamole is as good as anything in print today.

The Oxford English Dictionary attributes over a thousand words to Dampier, “many of them,” as Rupp points out, “having to do with food.” His was the first use in English of barbecue, breadfruit, cashew, chopstick, kumquat and tortilla along with soy. (Rupp; Fater)

By the beginning of the eighteenth century advertisements for the condiment had appeared in the London newspapers. Imports arrived from what then was the Dutch East Indies. Soon enough the original producers faced competition from an apparently unlikely source. In 1766 Samuel Bowen, an enterprising sailor, began manufacturing “Bowen’s Patent Soy” at his plantation outside Savannah and immediately began exporting it to England. During the same year the London based Society of Arts, Manufacturers, and Commerce awarded Bowen a gold medal for his sauce; he obtained a patent for its formula the following year. (Shurtleff 8)

The sauce went on sale at least as early as 1768 in Savannah itself. By 1770 it was sold in Newport; by 1773 in Charleston and 1774 in Philadelphia. The domestic product in turn faced competition imports that arrived all over British North America from China, the East Indies and, at least as early as 1818, Japan.

Its use in North America appears to have been ubiquitous beginning with the second half of the eighteenth century: Soy sauce appeared not only in seaboard cities large and small but inland in towns as obscure as Burlington, New Jersey, and Keene, New Hampshire. (Shurtleff 7-8, 120-30)

Soy sauce became so popular in England that by 1768 glassmakers were manufacturing specialized ‘soy cruets’ for service at table. (Shurtleff 8)

Contemporary version of an old sauce.

The 1784 edition of The Art of Cookery contains the first reference to soy sauce in a cookbook outside Asia. The relatively late appearance in connection with a recipe is easy enough to square with the considerably earlier proliferation of the product.

As the English craze for cruets indicates, for a long time soy sauce was used as a condiment rather than ingredient--as in inauthentic Chinese restaurants in the west today. And sure enough, Mrs. Glasse uses it the same way in 1784. At the end of a recipe for frying whitebait she instructs her reader to “drain them, and dish up with plain butter and soy.” (Shurtleff 124)

John Mollard followed in 1802 with at least two recipes incorporating soy sauce, “Anchovie sauce for fish” and “Oyster sauce for beef steaks,” from his Art of Cookery Made Easy and Refined. (Mollard 265, 130)

A year later Susannah Carter’s Frugal Housewife, which had appeared at least as early 1765 in Dublin and London, uses soy sauce for the first time in four recipes for fish; flounder or plaice, shrimp, skate and sole.

Soy sauce had become sufficiently popular that in 1804 an Michael de (and variously ‘von’) Gubbens provided a detailed description for preparing “the real Chinese soy” as opposed to earlier bowdlerized versions in three different London publications: the Journal of Natural Philosophy, Chemistry and the Arts; the Philosophical Magazine; and the Repertory of Arts, Manufactures, and Agriculture. During the same year the Domestic Encyclopedia out of Philadelphia also offered (considerably less detailed) instruction for making sauce from soybeans cultivated in Pennsylvania. (Shurtleff 153, 151, 154-55)

Then, the year before the New System reference appears, the 1805 London edition of The Lady’s Assistant by Charlotte Mason notes, erroneously, that “Soy is made from mushrooms which grow in the woods” in the East Indies. (quoted at Shurteff 155) So Mrs. Rundell was no pioneer in her use of soy sauce.

6. Here there and everywhere.

She did, however, exert a profound influence throughout the Anglosphere:

“In England New System extended to sixty-five editions in thirty-five years. In America, by the end of 1807 the book had been published in nine cities including Boston, New York, Philadelphia and down to Charleston, South Carolina, continuing to expand to at least thirty-seven American editions.” (Willan 79)

Willan’s selection of recipes from The New System is as impeccably chosen as the selection from The Art of Cookery. Lamb steaks or chops get stewed with the classic English marriage of lettuce and peas in a ‘hodgepodge;’ there is a chicken or veal pie loaded with parsley, although Willan has added spicing of ginger and nutmeg, which pretty much defeat the purpose of so much parsley, and finished with heavy cream; a formula for the highly spiced and indispensable mushroom ketchup. (Willan 83-90)

7. The scold.

Lydia Maria Child was a promiscuous reformer committed to abolition, Native American rights, womens’ rights in the fields of education, authorship, journalism and, according to Willan, “freedom for women to hold what were then scandalously liberal opinions. Her recipes are simple and successful.” (Willan 97)

The downside to her fervor: Child is a scold, one of the self-righteous reformers Hawthorne found so insufferable: “The mid-1800s were of course moralizing times but,” the otherwise admiring Willan has to admit, “Lydia seems to push the envelope….” (Willan 98)

Child wrote a guide to rearing children that reflects her cold and uncompromising character: “A child of six years old can be made useful… begin early. It is a great deal better for boys and girls on a farm to be picking blackberries at six cents a quart, than to be wearing out their clothes in useless play.” (Willan 101) Fortunately for the rising generation of her time, Child had no children herself.

If looks could chill.

The prolific Child wrote but one slight cookbook, her Frugal Housewife covering all of some one hundred pages. It is plagued by similarly hectoring directives that infest the recipes like interstitial cancer: “Time is money;” “No false pride or foolish ambition… should ever induce a person to live one cent beyond the income of which she is certain.” One section of The Frugal Housewife bears the enticing title “Cheap Common Cooking.” (Willan 98, 99)

A logical corollary of her thrift and parading rectitude, the recipes from The Frugal Housewife may work but the dishes that result are not particularly enticing.

Whatever her flaws, Child does deserve a profile from Willan: She chose her subjects because of their impact and The Frugal Housewife sold a lot of copies for a long time. She also wrote the wonderful “Over the River and Through the Wood,” a rhyming celebration of Thanksgiving set to music once memorized by every child in New England. Also to her credit; at least The Frugal Housewife includes an excellent (and of course cheap) recipe for an underappreciated Yankee delicacy, Indian Pudding.

8. A series of missteps in early national America.

If the profiles of Mrs. Glasse, Mrs. Rundell and an unappealing Child pack a remarkable amount of color and insight into their scant pages, the one for Amelia Simmons betrays an inexcusable lack even of secondary research along with some slovenly editing.

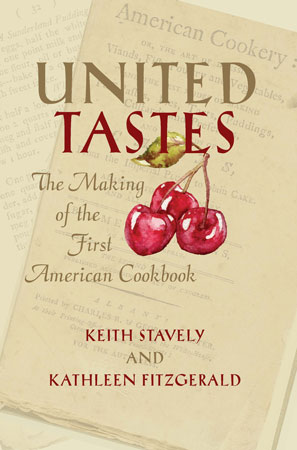

Any analysis of Simmons that does not rely on primary sources must begin, and end, with Keith Stavely and Kathleen Fitzgerald. United Tastes, their bravura interdisciplinary study of her book and the world that created it, has shoved aside everything previously written on the subject. Given the inaccuracies in her own profile of Simmons, Willan cannot have consulted United Tastes.

Simmons may or may not have existed. No evidence exists of her birth, marriage, the birth of any children or her death, an unusual recording omission for fastidious Federalist Connecticut assuming her persona is not an imagined one.

The slim volume attributed to her is, however, considered the first American cookbook. It originated in Hartford, Connecticut, during 1796, and was reprinted or plagiarized in various, shrinking, guises at other apparently unlikely places until 1831. It is by any conventional measure a bad book.

American Cookery is poorly organized; the chapter on preserves, for instance, “is rendered distinctly startling by the presence within it of recipes for ‘Alamode Beef’ and ‘Dressing Codfish.’” (UT 184)

Willan is unjustifiably credulous about the persona the creators of American Cookery invented for its putative author. She maintains that Simmons “appears out of nowhere” and “has no predecessors in print on either side of the Atlantic. She was,” Willan continues,

“a loner, an independent spirit who on the title page of American Cookery declares herself ‘An Orphan.’ There is no evidence she had access to any other printed cookbook…. ” (Willan 55)

No historical evidence supports any of those assertions and substantial evidence undermines some of them. No evidence indicates that, if indeed she existed, Simmons was orphaned, and presenting an author, real or imagined, as an orphan was a tired trope at the time.

Other than a more or less unhinged introduction and afterward the book itself is for the most part plagiarized or adapted from British sources, while its original recipes are, as Keith Stavely and Kathleen Fitzgerald describe them, “oddly truncated or rushed.” (UT 207)

9. The Connecticut way.

Stavely and Fitzgerald discern “a coherent social rationale in the book’s culinary content.” That rationale, they believe, developed out of powerful forces; the eighteenth century “expansion of Anglo-American cookbook publishing, the culture of print in New England, the social structure of early national Connecticut, the evolving American codes of refinement and egalitarianism, and the practices and attitudes relating to agriculture and trade in the region.” (UT 206)

Theirs is The Way.

American Cookery therefore represents a direct manifestation of, and to a limited extent reaction against, a coherent Federalist subculture indigenous to Connecticut--not an artifact that ‘appeared out of nowhere.’

It first spread, like the book itself, where, and only where, residents of the state emigrated. American Cookery found printers only in parts of New England, New York and Ohio, this “Greater Connecticut” as Stavely and Fitzgerald properly call it.

The ideal society that these Connecticut Federalists envisioned shares the sort of deferential aspiration that characterizes American Cookery. The connection is no surprise because Connecticut Federalists had a heavy hand in its creation and dissemination. ‘Simmons’ could not have produced the book alone; she probably could read but not write and therefore hired a transcriber, possibly one recommended by her publishers; the book reflects particular patterns of food production and consumption that were significant components of the Connecticut Federalist project; while the printers of her first and second editions were leading proponents of its dissemination.

Simmons therefore leveled her British sources by omitting all their numerous French preparations, because in “England, French cooking in unadulterated form was associated with the stratospheric reaches of aristocracy” and “such thoroughgoing social stratification was not to be permitted” in Connecticut. (UT 194, 195)

The distribution of American Cookery reflects and confirms a “Connecticut diaspora” of culture as well as people. As an example the locations of documented religious revival meetings organized by Connecticut missionaries outside their home state correlate to the places where the book was advertised, plagiarized or reprinted at the same times. (UT 261-62)

For all these reasons Simmons, if in fact she existed, is hardly the American original Willan describes. American Cookery does include some distinctively American characteristics, but it was the result of a broad collaborative project that emerged out of a longstanding cultural and political ethos, while its recipes are for the most part lifted from British sources. As for example Willan herself observes, the predominant influence on the cake recipes in American Cookery is English. (Willan 59)

10. Lesser infelicities.

Discrete factual errors also creep into the profile of Simmons. “Corn,” Willan claims, “was not the only ingredient mentioned by Mrs. Simmons that was unfamiliar to colonial settlers in New England.” (Willan 56) By the time American Cookery appeared, however, no colonial settler in New England was unfamiliar with corn; instead it had become an iconic regional ingredient, even avatar of regional identity. And no evidence exists about the marital status of the shadowy Simmons.

Willan compounds the confusion after making her dubious assertion about corn by reeling off emergent differences in British and North American nomenclature that do not describe unfamiliar ingredients: “Fat for making pastry is ‘shortening’ because it made dough ‘short,’ or crumbling; biscuits have become ‘cookies’ (from the Dutch koekje); and scones are called ‘biscuits’” except that to this day scones remain scones in the United States. (Willan 56)

On “Sea Pie” for instance Willan maintains that “[t]he name indicates it was intended to last during a sea voyage.” (Willan 58) Sea pie, however was made onboard ship from preserved ingredients and hardy vegetables. Its constituents but not the assembled pie itself, had to last a long time. The prepared pie would not.

While American Cookery deserves inclusion in a study that attempts to chart the development of American foodways, Willan’s is not the description the book requires and it is more than a stretch to elevate the Simmons character or construct into some sort of feminist success story.

As an aside that Willan does not address, why did the size of American Cookery shrink in an era of otherwise increased publishing sophistication in the cities of the young republic? It shrank to keep it cheap and enable peddlers to carry more copies to the frontier. (UT 259, 260)

11. The Yankee titan…

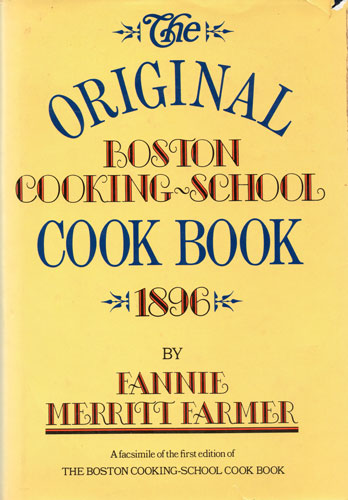

Willan gets back on track with Fannie Farmer, to some extent. All the American cookbook authors who preceded her were, as Willan maintains, lightweights by comparison. Her profile exudes admiration and the “lively affection” Farmer’s students at the Boston Cooking school also felt for her. Farmer’s personality informs The Boston Cooking-School Cookbook:

“Forthright and fluent, she expresses the spirit of her times and to this day her cookbook remains a valuable reference, an infallible guide to simple, everyday dishes.”

It does however go a little far to claim that Fannie Farmer, the informal title still universally used in New England, remains “irreplaceable.” (Willan 139) Her recipes are in many ways regressive: Any number of eighteenth and early nineteenth century cooks and diners would have lamented their lack of spice. Farmer’s devils for example feature nearly no fire; the cayenne that characterizes a dish authentically satanic has fled Farmer’s deracinated derivatives.

Savory dishes reliant on herbal tones are similarly diluted; stuffings seasoned with the merest dust of sage harbor only a hint of their former flair. To be fair, Farmer is not a temporizer all the time and her transgressions hardly are unique to New England. They mirror those of her contemporaries on both sides of the Anglophone Atlantic, reflecting as they do the timid tastes of the time.

Cooking times also skew against twenty first century products, no fault of Farmer’s but a trap for the unwary. Most pork for example is leaner now than then unless you find a heritage breed; chicken fattier, so cooking times that worked in 1896 require revision.

Nor did Farmer develop “the familiar recipe style we still follow now.” (Willan 135) It was Eliza Acton, half a century before Farmer, who first created the now standard recipe format that separates the list of ingredients with measures from the chronological instruction for their preparation.

Farmer furthermore does not uniformly follow the modern format. Many of her recipes, a vast plurality, do not segregate any list of measured ingredients. Instead they intermingle them within the archaic narrative form that fails to distinguish ingredients from their assembly.

Willan however is right if inartful in the telling that eventually Fanny Farmer would outsell all other American cookbooks that first appeared in the nineteenth century. (Willan 133)

In common with Simmons and other earlier American cookbook writers, Farmer’s work bears a distinct British cast. It also remains an iconic artifact of New England culture. As Willan notes, “….Fannie’s dishes… make clear the English heritage of the Yankee upper classes.” (Willan 134)

12… who knew high culture too.

Farmer owes a deep debt to English sensibilities. Not only her dishes but also her sensibility more generally skew English. Nobody appears to note any longer but the first edition of Fannie Farmer leads with a leading English cultural critic of a slightly earlier age as befits the Boston of her time.

It is, however, a truth universally unacknowledged that to begin her book Farmer quotes Ruskin, the aesthetic arbiter of the era:

“Cookery means the knowledge of Medea and of Circe and of Helen and of the Queen of Sheba. It means the knowledge of all herbs and fruits and balms and spices, and all that is healing and sweet in the fields and groves and savory in meats. It means carefulness and inventiveness and willingness and readiness of appliances. It means the economy of your grandmothers and the science of the modern chemist; it means much testing and no wasting; it means English thoroughness and French art and Arabian hospitality; and, in fine, it means that you are to be perfectly and always ladies--loaf givers.” (Farmer n.p.)

That last may not be the sexist subordination that modern minds might read it. Ruskin was a formidable scholar of English etymology, among many other things, and the word ‘Lord’ derives from the early English for ‘keeper of the loaf.’ Unlike their serfs feudal rulers enjoyed grand kitchens and the enlightened among them let their subjects bake bread in the great castles or manors.

Nor does his reference to France and the Arabian world in fact mean much to Farmer; the first edition of The Boston Cooking-School runs relentlessly English. The extension of that sensibility to the gilded age kitchens of Boston is exemplified by Farmer’s enthusiasm for forcemeats, although oddly enough their application is limited to fish soups. Forcemeat is the old term for stuffing, but traditional English cuisine extends it use beyond the cavities of birds and soups of fish. English cooks rolled the stuffing into balls for dropping into savory pie fillings and fried also for service beside game birds and other robust roast dishes.

The English influence is evident in so many of Farmer’s recipes including mock turtle, mulligatawny and pea soups; curried chicken, chicken livers, eggs, lobster (of course; this is Boston), mutton and veal (inexplicably called ‘India Curry’); veal birds; an array of sandwiches including the iconic oyster loaf more prosaically named; roast beef with Yorkshire pudding; anchovy, bread, caper, celery, mint, orange, oyster, Port, rum and three white sauces, and the ‘melted butter’ ubiquitous to eighteenth century English kitchens, in fact not merely butter but delicate blend of butter, flour and liquid that Farmer calls “drawn butter sauce” to add to the confusion.

None of that English influence should surprise anyone familiar with the history of Boston. Those Yankees still held cultural and political sway at the time the Boston Cookbook appeared in 1896, and had remained reluctant to embrace the Francophilia indulged by their neighbors in the City of New York. Willan claims that Brahmins then “lived in the Back Bay, a neighborhood of elegant brick row houses that overlooked the Charles River….” (Willan 132)

That, however, is not quite right. The elites of Boston did live in the Back Bay--according to the adage, people with family and money lived on Commonwealth Avenue, people with money but not family on Marlborough Street and those with family but not money on Beacon Street--but their houses do not overlook what then was the fetid river. Commonwealth and Marlborough have no river views; the houses on Back Bay Beacon turn the back on it. Finally the Brahmins themselves also lived on and under Beacon Hill in the older grand bowfronts to the immediate south.

Among other Farmer recipes, Willan reproduces and updates is the one for “The Original Boston Cream Pie,” which following the idiosyncratic logic of Bostonians is a cake. O for old Boston despite its depravities and prejudices.

12. Desperate straits redux.

Like Mrs. Glasse, Irma Rombauer wrote what would become a runaway bestseller out of necessity, even desperation. When her husband committed suicide following the crash of 1929, she found herself nearly destitute at the age of fifty four. “Instead of looking for a job, she decided to assemble a cookbook,” which she did, sequestered away from her St. Louis home at an inn in rural Michigan. (Willan 156)

According to Willan, the format Rombauer adopted for The Joy of Cooking owes much to Fannie Farmer but the recipes are hers, selected from some five hundred she had collected over more than three decades. Joy is by no means flashy, particularly exotic, original or distinctively Rombauer’s own but its bipartite strength is, as Willan understands, its breadth of reliable recipes.

Rombauer’s daughter tested them and created the artwork for her mother’s book, both its lively line drawings and Art Deco cover “in which the blue-robed St. Martha of Bethany, the patron saint of cooks and domestic servants, is seen slaying the brilliant green dragon of kitchen drudgery.” Wonderful, and wonderful of Willan to highlight the saint and her quarry. (Willan 157)

By 1995, expanded editions of Joy had sold hundreds of thousands of copies, another echo of The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy, and in 1995 it was the only cookbook the New York Public Library included on its list of the one hundred fifty most influential books of the century. (Willan 159)

13. Another woman of great stature, based in Boston.

“Julia Child,” as Willan writes, “led two lives. The first was as a sociable international housewife. The second began when, at the age of fifty-one, she appeared on a public television show and became a celebrity.” (Willan 177) In fact Child had also lived a third life.

Like Elisabeth Ayrton, who supervised a large staff for the British Special Operations Service and went on to write luminous cookbooks, Child was a formidable intellect who managed to transcend what then was the circumscribed role of women in military intelligence. She worked for the American Office of Strategic Services during the Second World War, when she was posted to Sri Lanka and then China.

Also like Mrs. Ayrton, Child was a towering figure literally as well as figuratively. The parallel continues: Both of these tall, striking women were politically liberal atheists educated at elite institutions whose de facto religion was generosity.

Child refused to take her work or herself too seriously on the program--she had seen too much conflict for that--appropriately enough called “The French Chef.” It was informative and immediate; broadcast live, its producers never edited away mishaps or malaprops, so the show was often hilarious, sometimes inadvertently so, sometimes with the sly connivance of Child herself. Her viewers adored it.

It is easy to see why Willan harbors at least as much affection for Julia Child as she does for Farmer. Willan knew Child well and her admiration for ‘the French chef’ is justifiably boundless. Child would throw small informal dinners at her house in Cambridge; Willan was fortunate to be a guest at some of them so is privy to domestic detail. The fastidious Child, she explains, got

“….the freshest Massachusetts fish and meat from her nearby artisan butcher, Mr. Savenor…. ” (Willan 179)

Of course not all the fish and meat could then have been sourced from Massachusetts, a minor point, but the consistent quality of Savenor’s products remains unsurpassed. The magical shops still exist, in Boston as well as Cambridge, and Savenor’s sells good game, cheeses, spice and other groceries as well. In a reflection of the establishment’s roots, Savenor’s is the official butcher of the Boston Red Sox, in New England an honor akin to a royal warrant in the United Kingdom.

Child’s Mastering the Art of French Cooking from 1961 remains probably the most famous cookbook published in the United States. Preposterously, the book had difficulty finding a publisher. Fortuitously the publisher who finally accepted the book was the legendary Judith Jones at Knopf who deserves a plinth in the American culinary pantheon.

14. A child of the Great Migration and a different kind of love story.

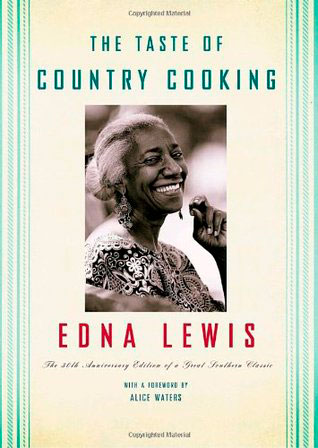

All her life, at first out of necessity but later by choice, the entrancing Edna Lewis anticipated the current obsession with local and seasonal ingredients:

“For the young Edna,” Willan writes, “cooking was inseparable from the earth and the seasons: First came the wild asparagus, the leafy tops of baby beets, then new potatoes, wild strawberries, fillets of shad….” (Willan 214)

Once again Willan describes delicious details; Lewis grew up poor in a large family at Freetown, Virginia, on land an enlightened planter granted to freed slaves immediately following Emancipation. Sixty years later nearly nothing had changed. Theirs were segregated lives; ice came from the nearby town of Lahore, which from its name had to have been a black enclave too. (Willan 213, 214)

Like the patricians Ayrton and both Childs, Lewis, the homeschooled child of illiterate parents, was a committed liberal. She would become a gifted, self-taught cook and writer. Lewis left Freetown with the Great Migration, first to Washington, DC, and then to New York where despite the endemic racism she flourished. Her dynamic personality attracted the attention of influential New Yorkers including John Nicholson and Jones, who became her editor too.

One result was Café Nicholson, the Upper East Side celebrity magnet. Lewis co-owned the restaurant with Nicholson and ran the kitchen for decades. Another was her second cookbook, the evocative and iconic (nineteen editions) Taste of Country Cooking, also published by Knopf. Alice Waters, herself one of Willan’s profiles, is right to claim that Lewis describes “the glories of an American tradition worthy of comparison to the most evolved cuisines on earth.” (Willan 220)

Lewis was a founding member of the indispensable Society for the Revival and Preservation of Southern Food where she met Scott Peacock, a white Georgian forty seven years her junior, “when cooking at a charity event in 1990” at the age of seventy four. (Willan 219, 220)

In one of the most moving encounters of culinary history they became inseparable and wrote the peerless Gift of Southern Cooking together at their house in Decatur during 2003. Peacock continued to look after Lewis there until her death three years later. Willan is properly generous in recording his role.

15. Short shrift.

The profile of Marcella Hazan is oddly inert. Hazan was a difficult character; unlike Child, for instance, or Lewis she quarreled even with Jones, who also edited her work at Knopf. Willan struggles with the profile, perhaps because she could not warm to her subject.

The perfunctory essay on Alice Waters reads something like a canned obituary reciting some facts, providing some color but lacking insight.

Waters was another child of liberal activists and would join the Free Speech movement at Berkeley and the Congress of Racial Equality. Early on however she turned to cooking and brought to it the same uncompromising principles as she brought to her political beliefs.

More mars the profile than omission. A particularly perplexing passage: “In France, Alice learned to eat, a talent that never left her.” (Willan 263) Whatever that is supposed to mean it contradicts Wilan’s narrative describing Waters’ recollection of relishing comfort foods before she set foot in France; bacon and avocado sandwiches, grilled cheese with pickles, roast turkey, jelly doughnuts and homemade ice cream.

Even though the essay runs to only about six pages it is repetitive and unfortunately exhumes the tiresome Brillat-Savarin quip about being what you eat. Perhaps Willan had run out of steam or tired of the project toward its end. Still, she does give her reader some sense of the uncompromising Waters and her rigid technique.

16. Some other stumbles.

Other passages exhibit other signs of haste; repetition is rife and other passages are as peculiar as the one in which Waters ‘learns to eat.’

On plagiarism, Willan repeats a dubious assertion about the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries:

“At this time … plagiarism was common practice and indeed approved--it was an author’s duty to pass on the finest recipes, with no insistence on originality (Willan 34): … at the time, plagiarism was not regarded so unkindly as now, though copyright was recognized and enforced.” (Willan 34, 14)

That is not quite right either, not when it comes to cookbooks. Plagiarism of cookbooks was indeed widespread but its victims disapproved intensely of the practice and nothing indicates that contemporaries recognized any such ‘duty to pass on the finest’ or for that matter any ‘recipes.’

In addition, the reference to copyright enforcement is confusing because, until 1909 in the United States and continuing today in the United Kingdom, copyright law does not apply to recipes unless they are considered somehow unique, a difficult legal proposition to prove then and difficult to prove now.

On contiguous pages Willan repeats the assertion that the style of women historically differs from men in that womens’ recipes are simpler, less expensive and homelier than mens.’ Willlan provides no example of the distinction or citation of it but, this time without reference to plagiarism observes that Hannah Wooley “borrows from at least one earlier author, Sir Hugh Plat, who like other gentlemen enjoyed experimenting in his ‘elaboratory,’ a sort of kitchen.” That would appear to place the claimed dichotomy between male and female styles in question. Then again to Willan’s credit the reference to an ‘elaboratory’ is revelatory. (Willan 4, 5, 14)

Willan declares twice that Hannah Glasse was “dressmaker to the Princess of Wales;” elsewhere she identifies the royal patron as the king’s sister, Princess Charlotte” without reference to the Princess of Wales. (Wilian 6, 32, 4)

Elsewhere it is gratuitously anachronistic of Willan to claim that Sarah Rutledge, whose cookbook first appeared in 1851, “might have been appropriating…. a sprinkling of recipes” from the Native American tradition. (Willan 118) She no more appropriated her recipe incorporating squirrel and sassafras than Native Americans appropriated the beef or pork unknown to them prior to the arrival of Europeans in North America. In any event squirrels inhabited England before any settlers arrived in its American colonies.

17. Keepers of the flame then and again.

None of these foibles may matter much to recreational readers and, other than the profile of Simmons, Willan has at the very least given them an introduction to some worthy writers and their recipes.

None of these authors is an innovator in substantive terms. Waters may have changed the way Americans considered the restaurant but the simplicity of her cooking hardly may be considered pathbreaking. That is not to denigrate her or any of the other women Willan profiles. Each one consolidated, even codified traditional methods as a means to reintroduce them to a wide readership. That is more than enough to earn our gratitude.

Sources:

Clarissa Dickson Wright, A History of English Food (Kindle ed. 2011)

Fannie Merritt Farmer, The Boston Cooking-School Cook Book (orig. publ. Boston 1896; facsimile first edition Weathervane Books, New York n.d.)

Luke Fater, “The Pirate Who Penned the First English-Language Guacamole Recipe,” Atlas Obscura, https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/first-food-writer (26 July 2019) (accessed 31 October 2020)

Heller McAlpine, “Food,” The Wall Street Journal (21-22 November 2020)

John Mollard, The Art of Cookery Made Easy and Refined: Comprising Ample Directions for Preparing Every Article Requisite for Furnishing the Tables of the Nobleman, Gentleman, and Tradesman (London 1802)

Blake Perkins, “An Enquiry into the Derivation of Chowder,” Petits Propos Culinaires no. 109 (September 2017) 32-67

Rebecca Rupp, “Eat Like a Pirate,” National Geographic, www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/food/the-plate/2014/08/19/eat-like-a-pirate/#close (19 August 2014) (accessed 31 October 2020)

William Shurtleff & Akiko Aoyagi, The History of Soy Sauce (Lafayette CA 2012)

Anne Willan, Women in the Kitchen: Twelve Essential Writers Who Defined the Way We Eat, from 1661 to Today (New York 2020)