Occasional Miscellany: The lost soups of Belfast.

Imperial innovators.

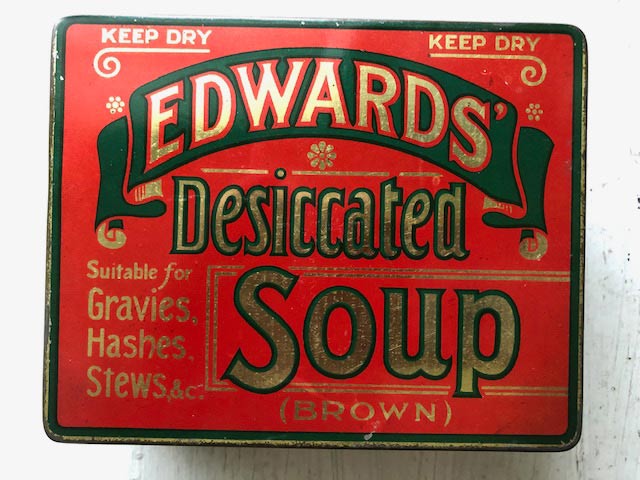

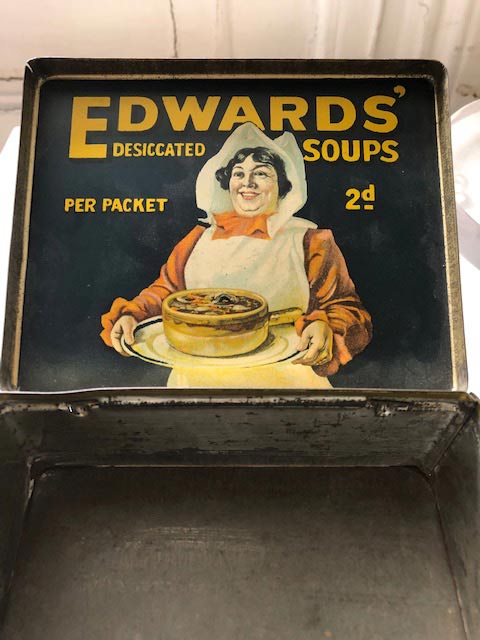

It remains possible to find attractive hinged tins from the late nineteenth and early twentieth century that held Edwards’ Desiccated Soup. The descendant of portable soup and ancestor of the stock cube was the creation of Ulster entrepreneurs. The business, more properly called Frederick King & Company, originated in Belfast and expanded into a transnational enterprise with offices in Glasgow, London, Manchester, Montreal and New York. (belfastentries)

People have short historical memories and few recall that imperial Britain was an industrial powerhouse. Fewer still realize the prominent role Ireland, and in particular the north of Ireland, played in the industry and commerce of empire. The industrial ascent of Britain itself has overshadowed early innovations and investment in the south, especially during the transport and commercial revolution that presaged the era of British manufactures.

Industrious Ireland.

“Ireland,” as Colin Rynne insists, “performed quite well compared to other European countries” citing Belgium and the Netherlands as relative underachievers. “In the 17th century,” for example,

“Irish ports were the cornerstone of English [sic] transatlantic provisions trade. It had one of the best road systems in Europe in the 18th century.”

Like so many Irish people Rynne cannot escape defining Ireland in terms of its bigger neighbor to the east. Dublin paved its streets before London--the Ascendancy held unlimited aspirations for the capital and Rynne might have added that its eighteenth century parliament building eclipsed its counterpart at Westminster--and the Newry Canal was the first “summit level” passage in the empire connecting water drainage regions.

Ireland did not sit out the industrial revolution either, although most manufactures emerged from Ulster factories. Belfast itself was a sort of Irish Chicago without the storied skyscrapers, a “busy and progressive city” of rapid growth marked by extensive innovation.

Rynne points to “a huge linen industry in the North. The Harland and Wolff shipbuilders,” he adds, “were the largest in the world in the 1920s and 1930s, employing almost 30,000 people.” Back in Dublin Guinness operated the biggest brewery on the globe. (Thompson)

An Irish archetype.

The seedling of the Edwards empire was archetypically Irish. The fact that the company began its ascent in 1840 by inventing a means to preserve potatoes through dehydration is almost too delicious to recount. From its inception the enterprise was an example of vertical integration, growing its potatoes on extensive farms at Ballyherly in County Down, where according to a late nineteenth century source the firm also operated its

“extensive and perfectly equipped works, fitted with every special appliance for the preparation of the preserved potato under conditions of the utmost cleanliness and hygienic perfection.”

Ruling the waves.

By 1843 the Admiralty already had “secured large quantities of this unique product.” A Royal Navy Medical Committee believed the Edwards’ Preserved Potato was an effective antiscorbutic because of its “valuable mineral salts.” The United States Department of War followed suit and continued purchasing preserved potatoes throughout the century. (Belfast entries)

One of those nineteenth century Belfast innovations emerged during the 1880s in the form of Edwards’ soups, a logical enough expansion of the company’s dehydration capability. Varieties included a vegetable soup with beef extract, tomato, a white soup “recommended for vegetarians” (itself something of a progressive nod) and another offshoot, Gravina-Edwards’ Gravy Powder “composed solely of the finest extract of beef.”

Soup for all, then none.

Edwards’ soup flourished up and down the social ladder in both Great Britain and North America, which accounts for the availability of the attractive tins that contained it. Enthusiastic purchasers of the Irish product sent testimonials from as far away as Arkansas, Georgia and New Jersey.

“In an area of extreme poverty,” one commentator believes, “the low cost soup mix was literally a life-saver. The Edwards’ dried soup preparation became a household name. It was much valued for private family use as well as by restauranteurs,” unlikely as that would appear today.

After the second world war however sales of both potato and soup faltered until bankruptcy befell Frederick King & Co in 1960. (belfastentries) At least, however, the busy metal boxes abide.

Sources:

Anon., “Step Forward Mr Edwards and Messrs Frederick King & Co,” Belfast Entries, https://www.belfastentries.com/products/edwards-desiccated-foods/#:~:text=In 1840 Mr Edwards%2C who,a helping of mashed potatoes (n.d.) (accessed 14 March 2022)

Sylvia Thompson, “Ireland’s industrial heritage: the past you might not know we had,” Irish Times (22 August 2015)