A consideration of Charlotte Du Cann, featuring fashion, fine art, food, sex & Dark Mountain.

1. Hedonism and its shadows.

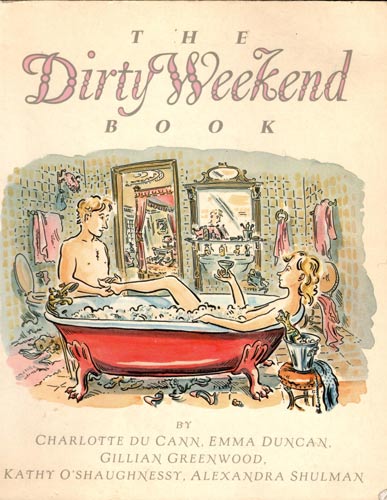

“Man,” warns Charlotte Du Cann, “cannot live on cocaine and champagne alone.” (Dirty Weekend 21) The lament was heartfelt enough in 1984. Now however Du Cann would forego either indulgence and insist that humanity--gender sensibilities jostle among the things in her orbit that have changed--can, and should, live on beans alone provided another kind of comfort stays close to hand.

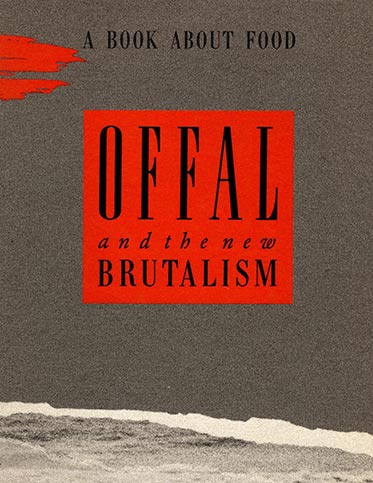

It therefore is inadvertently fitting that, at the outset of Offal and the New Brutalism written the following year, she warns her readers to temper expectations:

“This is not a recipe book. This is not a diet book. This is not a book that will tell you your arteries are clogging up. This is not a book that will tell you where in France I ate the perfect ficelles cooked by my friend Jacques. This is not a book to show you how the Flopsie Bunnies like their lettuce. This is not a book to show you how the jeunesse dorée like their quails eggs. This is not a book of cartoons of chefs. This is not a book of photographs of cakes. This is, however, a book about food.” (Offal frontispiece)

It is the first of many misdirectives. Du Cann engages in social satire across a range of subjects by no means limited to food, which in reality is not her focus. Targets include aesthetes, fashion, the ‘Heritage’ nostalgia machine, publishing, restaurant culture, Thatcher and Thatcherism.

2. Much in vogue.

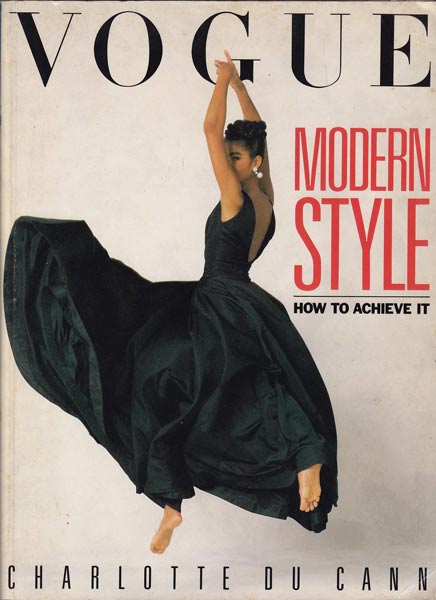

Du Cann is a conflicted character. For years she inhabited with apparent enthusiasm the demimonde Offal satirizes, as writer and editor variously at Harpers & Queen, Tatler and British Vogue, all the while enthusiastically dining on fugu and other dubious delights. (“Uncivilising the Table”) Her connections within the retail establishment were impressive. She wrote or co-wrote a number of books on fashion, consumption more generally and the louche life, among them a manual for the ‘achievement’ of high style, a shopping guide to London published by Virgin Books in association with London Transport, and instructions how to engage in The Dirty Weekend.

Vogue Modern Style: How to Achieve It is very much an artifact of the publication that commissioned it and of its 1988 time. It also entails an inadvertent irony because Modern Style celebrates that haughty haut monde she savaged three years earlier with Offal.

When she put together Modern Style Du Cann wielded considerable clout in the fashion industry. Photographers who contributed to Modern Style include the heavyweights, among them David Bailey, Patrick Demarchelier, Mario Testino and Bruce Weber. By the time she wrote it Du Cann had moved on to one of her other glossies but Modern Style nonetheless captures the inane timbre of the Vogue voice:

“Though emphasis on the word style has implied individuality, in reality it means choice. Not one style for each person but several styles for everybody.” (Modern Style 13)

And so the corollary:

“The consumer age said, Look at this! Do you want it? Have it! All things became instantly purchasable, dream homes, dream holidays, dream frocks.” (Modern Style 11)

Elsewhere Du Cann claims a unique freedom for the Modern British Girl. Sort of: “This liberty to dress according to your pleasure, not according to status and price tag, is a British quality that does not exist in other countries,” but then again a contradiction; “it is widely copied.” (Modern Style 14)

3. Depression Modern, jumbled nations and Action!

Although Du Cann disavows the notion, Modern Style amounts to a manual for choosing the couture required for playing adult dressup. It ranges across countries; “boulevard chic,” “Country,” which has nothing to do with hunting (that gets its own look along, inevitably, with shooting and fishing) or rural England more generally but rather purports to channel the American Midwest along with the even more incongruous “Thirties Dustbowl” look; “Ethnic,” which in fact appears to refer to Asia alone; also an overlap, “Japstyle [!]” or “the supreme modern style that yanked fashion from its seventies nostalgia right into the monochrome eighties.” (Modern Style 49)

Her “Spanish Style,” in fact however is “a hot Latin mix of Brazilian dancer,” who incidentally would speak Portuguese, “Madrid matador and Mexican movie extra” but “don’t overdo the gypsy connection, you do not want to be taken for a fortune teller.” (Modern Style 32) Yikes.

Du Cann covers ‘historical’ styles other than Dustbowl including “Air Raid Forties,” uniforms from schoolgirl to Royal Navy and genres in general (schoolgirl of course qualifies for that category too when it comes to a Dirty Weekend and the like); “Action!” including “Bike Style” which “is to sex what singlet style is to comfort” along with a cautionary “Bikenote;” “bike helmets and fluorescent warning bands may be sensible for cyclists but they are in no way cool.” True enough because “Bikers like it mean and dangerous.” (Modern Style 64)

Other Actions!; “Ice!,” “Jump!,” “Ski!” (“a love affair with the slopes, not a professional commitment”) (Modern Style 73)

References to food recur. Gaucho pants, ponchos and sombreros are “Spanish Omelettes.” And an evocative, thoroughly British and silly simile: “Fashion without detail is like mutton without caper sauce, perfectly fine and dandy but O so much more delicious with.” (Modern Style 162)

4. More sex please, we’re British.

Although written from a woman’s perspective, The Dirty Weekend Book could not be considered enlightened let alone feminist. Some sound advice however. On yoga: “You’re in a tricky enough position without encouraging fate further.” (Dirty Weekend 37)

On preparation:

“Anyone who’s embarking on a dirty weekend without having tested the quality of the ‘dirt’ first, has got a promising area for disaster. First-time sex is normally pretty second-rate and when complicated by the arrival of room service, double beds that turn twin unannounced and the loud voices of the couple next door, it’s up against high odds.” (Dirty Weekend 147)

On clothing: “Night. DON’T wear your chiffon or worse, nylon-gauze negligee. Nudity is Natural and Nice.” (Dirty Weekend 34; capitalization in Coy Original) But then in Modern Style Du Cann advises her reader that “French knickers” are fine “if you’re not wearing anything else,” but again “Never nylon.” (Modern Style 102; emphasis original)

Ok for the Vogue Du Cann.

Ok for the Vogue Du Cann.

5. Much Depends On Dinner.

Dinner is of paramount importance to the Dirty Weekend for any number of reasons. “For one thing, it’s a crucial acid test if you don’t know each other too well.” The signals ‘he’ inadvertently sends during dinner provide crucial clues to the prospects for the Dirty Weekend. “If, for example, he refuses a drink, send yourself a telegram immediately. There are all sorts of explanations, none of them encouraging.” (Dirty Weekend 21)

“Food as ritual” may promote potential coupling, sometimes. Breaking “bread/melba toast/prawn cracker together” symbolizes

“the sharing of the substance of Life (though given the vogue for nouvelle cuisine these days, that theory is clearly going to have to be revised. Most nouvelle cuisine dishes wouldn’t sustain a vole.)”

‘His’ culinary choices may be portents, most apparently negative, of personality. Vegetarians, ironically enough as it will turn out, are, categorically, “To be avoided.” An order of fish is “symptomatic either of past excesses, or of a feeble constitution. Either way, you have a sleepless but dull night ahead of you. And there is a reasonable chance he will start telling you about his ulcer.” And yet “poached fillets of sole in a light sauce” or salmon trout can be good selections for either conspirator. (Dirty Weekend 154, 152) Consistency never has been of real concern to Du Cann.

A selection of spaghetti betrays “a thoughtless type.” “There is little more off-putting than an orange sticky chin, and a bright white shirtfront speckled with sugo…. ” Then again the taste for steak au poivre is a good omen: “Challenging. He likes a dish that bites back.

Some “selected inklings” that follow on food choice involve the delphic clarity of ancient prophecy. “You may find,” Du Cann explains, that if he orders steak au beurre “you get the same treatment later on.” (Dirty Weekend 22) Is the butter a reference to Last Tango? To advanced oral technique? More generally to a voracious taste for the enriched experience? We cannot know.

For your part dangerous agents lurk in the kitchen.

“Nothing is going to make you feel erotic, for instance, if there is a deadweight of steak and kidney pudding lying dormant at the bottom of your stomach. Most Indian food is fine, so long as your stomach has the sensitivity of a boot and you positively want to stay awake all night to make trips to the loo.”

Other commodities entail overt innuendo. “Asparagus is wonderful as far as sensitivity, sensuality and symbolism go,” but Du Cann departs from Proust on its sexual perfection: “the other side of the coin is the sight of those attractive little drops of grease making their way down your shiney chin.” And an unambiguous phallic faux pas: Sausages are out: “the sight of you tearing one to pieces is not calculated to make him feel comfortable.”

In the end all but a single selection is not problematic in terms of prediction and it is predictable enough: The oyster. “Very promising. Shows a sensitive appreciation of the most delicate sensations. In other words, a good lover.” And for ‘you’ “the only really safe choice.” (Dirty Weekend 23) As a bonus they pair well with all that champagne and cocaine.

“Another good reason for having dinner,” despite its attendant risks,

“is to eat. Hemingway-esque ideas about heightened sensations on an empty stomach are all very well, but there’s little point to going off for a Good Time if you’re going to feel bad-tempered and fantasize about Mars Bars…. ” (Dirty Weekend 21)

6. Precautions and prejudice.

More problematic to woke sensibilities and #MeToo would be advice to stock Duran Duran recordings for the weekend “if girl/boy qualifies as jailbait.” (Dirty Weekend 181) Or advice about lying: “There’s no practical difference between a fib and a real whopper. So be brazen.” (Dirty Weekend 183) Then the specifics of scheming. A camera is essential “for blackmail purposes in years to come, esp. if he becomes famous; if he’s already famous take the picture sneakily… (The Sun pays best.)” (Dirty Weekend 27)

But all of this was meant to be fun and somebody benefited from the book. The original owner of our copy penciled in the telephone number of the Lower Brook House hotel in Blockley (Du Cann: “Blockley is not the prettiest village in the Cotswolds--thank God!”) and also corrected the printed cost to stay there. (Dirty Weekend 139) She had written the number of the Chedington Court in Beaminster as well, with ink.

7. A Bible and the bible.

Some hotels Du Cann recommends also appear in The Sex Maniac’s Bible, one of several projects undertaken by the prolific Tuppy Owens to promote all manner of sex. In common with Du Cann, Owens recognizes the erotic connection to the culinary with her High Teas: Easy-To-feed Each Other Recipes.

Other publications have included The Organ, Sexual Paradise (“With over 150 Colour &b/w photographs”), Shaggy Birthday, 12 Steps to Heaven, More Steps to Heaven, Politico Frou Frou (with Christopher Jones), The Summer Holiday Sex Manual, Take Me I’m Yours--Guide to Feminine Psychology and Supporting Disabled People with Their Sexual Lives, an explicit and humane handbook for a sorely underrepresented demographic that happily remains in print. Owens also founded “Outsiders,” an advocacy organization that provides advice and information about sex and sexuality for disabled people, an exemplary cause.

Now rendered irrelevant by the internet along with so much else, in its day the Bible was an indispensable global guide to campsites, celebrations, clubs, conventions and colonies for everything from kink and fetish to naturism, orgies, sexualized science fiction and sci fi role playing, swinging and, during its existence from 1991 until 1999, the quadriplegic artist Frank Moore’s Cherotic Movement, “where strong lusty women are redefining and expanding sexual, spiritual and social concepts of life, and influencing anarchic teenagers who are searching for positive values.” Good for Moore and the Movement.

Another of Owens’ efforts, The Sex Maniac’s Diary, is similar to her Bible but concentrates on time as well as place and includes daily sex positions as well as a weekly quotation and “Condom Survey.” Among the quotations is a rarity from Tom Lehrer of apocalyptic comedy fame:

“Pornographic pictures I adore,

Indecent magazines galore,

I like them more if they’re hardcore!

Bring on the obscene movies,

murals, postcards, neckties,

samplers, stained-glass windows,

tattoos – anything!

More! More!”

The accompanying condom manufactured by Okamoto is “sea green,” has “lovely lubrication” and “smells appealing” but “tastes very bitter.” (Sex Maniac’s Diary n.p.)

Another quotation is biblical but not from the St James version, which appears to have lost a lot in euphemistic translation. Western versions of proverbs 30:16 typically refer to a ‘barren womb’ but reference to sterility looks like a demure corruption of the original. Earlier translations including the Coverdale Bible from 1535 omit it and, according to the delightful “Bawdy Bible” by Edward Ullendorff, ‘womb’ and ‘vulva’ apparently are synonymous in the ancient Hebrew. (Ullendorff 442, 442n57) All that indicates Owens is on to something when she gives the proverb an overtly sexual cast and, just perhaps, a celebration of female sexuality scrubbed by the squeamish from the foundational text:

“There are three things

that are never sated…

Hell, the mouth of the vulva, and the earth.”

(Sex Maniac’s Diary n.p.; elipses in original)

8. A problematic penchant and antipathy to pink.

Du Cann’s attitude, or perhaps former attitude, to the LGBTQ+ is not altogether admirable. While TDWB notes that the clandestine couple need not necessarily involve people of differing sexes, Du Cann includes a “type” who “can be fun but is also a bit of a risk.” “Rough Trade” has “a penchant for showin’ a bit of aggro” and “mutters for hours on the subject of ‘poofters’ ‘woofters’ and ‘benders’” but then again “he’s terribly good in bed” and “makes brutal love to you on the floor, sexily ripping your skirt in the process.” (Dirty Weekend 144)

“Novel Cuisine” from Offal goes further, to savage gay culture in the form of Edmund White’s Boy’s Own Story as “pretentious literature…. that picks its ingredients and style from another’s cuisine and has none of its own. It looks good and tastes of nothing.” (Offal 89) Du Cann elaborates: “1983 was the pretty boy era.” The cover of A Boy’s Own Story, she observes, “had a pretty boy in a dusty pink (as in triangle and THE colour that summer) singlet…. A perfect dish for boys. How could they resist it? They didn’t.” (Offal 89, 87; emphasis original) This species of casual bigotry should have provoked comment even before this hypersensitive era.

9. Biting the hand….

Elsewhere Offal takes on cults of masculinity and worldliness. The titular story refers not to the architectural style but to ersatz savagery, a lost opportunity. Hemingway recurs as a paradigm bad actor in Du Cann’s hedonistic phase. Real men eat bloody slabs and guts:

“The English men are all eating offal! Can you believe it…. Hell, well the Hemingway boys had been here before me. (So long Keats baby, this ain’t no time for poetry.) The hard men had swaggered into the kitchen left open by those careless ready-packed microwave girls and they had thrown out all the mousses, and gateaux and the little creamy chicken dishes and made RED MEAT the priority.” (Offal 32)

The stories in Offal are bitter, knowing, funny if sometimes obvious on subjects ranging from the California film industry to the United States more generally.

“Fast food is what America has instead of history. No Acropolis, No Versailles, No Blenheim, no Venice, no palaces for feasts, no gardens for picnics [particularly important it turns out to this incarnation of Du Cann]. In fact no dinner at all. Just the Hollywood hype machine telling you the myths and gods are out there on the pavement…. ” (Offal 91)

Du Cann is however good on the forced American informality that

“wowed the English all this phonyfriendliness because they are such scaredy cats in restaurants. Especially when they have left you their names on the bill: Jackie, XXX HAVE A NICE DAY.I mean, when I want personal interaction I wear deodorant.” (Offal 26)

10. Regret and resentment.

Then something happened. At some point Du Cann concluded that fun was no longer fun, no longer worthy even of parody. Her sense of humor evaporates. Du Cann ditched her devotion to luxuriant consumption, sold her books, stopped reading literature. The decision entailed no small sacrifice. Du Cann describes a preconversion “alchemical workplace of words and cooking pots,” the “kitchen study” in which she is “surrounded by everything I know: shelves of books, thousands of them.”

In a way she resents the comfortable world she had created and the guests who reveled in it, “rooms with a certain atmosphere many people love to come to, even more than being with me.” (“52 Flowers” 2) Du Cann rues for two reasons her friends’ reaction to the sale of her books: “And they were shocked that I should do such a terrible thing (more upset it seemed than by my imminent departure.)” (“Benchmarks” 1) Her friends, she appears to have concluded, were not so friendly.

11. Picnics and epiphany.

The exuberant early work hints at what will come, a stirring unease with not just fashion and the fast lane but also about the effortless and elegant. The best essay in Offal, “The Picnic Box,” considers a flawless but increasingly wistful young woman famed for “her extraordinary ability to hold fabulous parties,” affairs so essential to attend for their style and connections that “opera tickets were torn up and family visits cancelled and holidays postponed etc. etc.” (Offal 99-100)

Alex Montgomery “was the sort of girl who read newspapers in trains without losing her cool. With a swift flick of the wrist she could turn from the Home News to the Art Reviews and never have the Letters slip.” (Offal 99) That was a formidable feat back when people read broadsheets and rode trains.

The old ideal.

The parties are so influential that if Montgomery

“chose a colour such as her Monochrome or Shocking Pink Parties they would as if by magic be in next season: if Alex chose a country as in her Catalan or Bourbon and Blues Parties, there would be immediate talk about bullfights and a rethink of America.” (Offal 100)

Then she rummages for a dish in the attic, “dark and warm, quite cut off from the rest of the house, like another country.” It is the past and the future. There Montgomery stumbles upon a picnic box “with worn straps and squeaky dark wicker” among the “diaries from her school days and a book of Yeats poetry she had been given as an English prize one year” along with “old Christmas decorations she never used, and dressing-up clothes for the children that never lived there.” (Offal 101) Dressup and Du Cann have a history.

The box provokes memories that will afflict and then enlighten her.

“We took the box… and waded ashore and lay there all afternoon… swapping limericks and smoking cigarettes and cooking potatoes on a little stony fire.

I don’t like potatoes, not any more. What did it belong to all that picnicking and relentless filling of baskets? Was it meant? I who have eaten in the finest restaurants in the world and am such a brilliant hostess cannot remember a time when I ate such a meal as those burnt tubers.” (Offal 103; emphasis original)

Montgomery chucks everything following her last party, a party she knows must fail. She prepares her guests for the Picnic Party with neither conceit nor dress code because neither matters anymore. She wears “workman’s trousers and a navy jersey.” (Offal 104) She has emptied her house of “the magnificent mahogany,” torn out the curtains and thrown open the windows. It is cold; everyone is physically and emotionally discomfited. Nobody likes sitting on the floor and no connections of convenience consummated.

“On the floor on an old brown and white travelling rug sat the snowdrop china from the picnic box. It bore plates of cold chicken and slices of ham and baked potatoes and hard boiled eggs and small rather unripe looking tomatoes. There were brown bags filled with wrinkled winter tomatoes and several loaves of coarse brown bread and tumblers to drink from…. The wine was not chilled, the sausages were burnt and there were not enough crab claws to go around.” (Offal 105)

12. Devotion to darkness.

“Alex,” her guests agreed, “had everything going for her you know and she gave it all up.” Alone after the party in her empty house Montgomery knew better. “Tomorrow, she thought, I shall go. I shall take the box and no one shall stop me.” (Offal 105, 106)

Du Cann herself would become vegetarian and an ecowarrior of sorts, more an ecodefeatist devoted to the Dark Mountain movement. (“Uncivilising the Table”) ‘Acceptance’ of ‘Uncivilization’ are the watchwords of Dark Mountain but it would be more accurate to describe the perspective of its followers as nihilistic masochism. The cheery title of its Fall 2021 blog, “Abyss,” encapsulates the Dark Mountain ethos of despair.

It is as if, as Stephanie Dearmont has remarked, Du Cann had suffered a stroke, although she herself ascribes the transmutation to a kind of education. Either way Du Cann has lurched from one soulkilling world to another without the self-awareness of her former persona.

When the founder of Dark Mountain, Paul Kingsnorth, describes the movement, “he speaks of mourning, grief and despair.” His followers believe climate change is both catastrophic and irreversible and oppose any means to meliorate the disaster. “What do you do,” Kingsnorth has asked The New York Times,

“when you accept all these changes are coming, things that you value are going to be lost, things that make you unhappy are going to happen, things that you wanted to achieve you can’t achieve, but you still have to live with it, and there’s still meaning, and there are still things you can do to make the world less bad.” (Smith)

That last question might imply that maybe a shard of hope might glimmer but no, out flies the rug: Kingsnorth has no answer other than individual accommodation to the inevitable.

Nor does he identify what things climate change has made him personally unable to achieve. It looks difficult to imagine what they may have been or may be. After all, the disconnection between the immediate impact of climate change in the short term and on any particular person is a high hurdle to convincing skeptics of the need to address it.

13. Hallucination, death and… Castaneda?

In the case of Du Cann accommodation appears through the agency of peyote in the guise of death. The hallucination dissipates for most people with a little time but Du Cann would appear to have experienced a more or less permanent altered state not least in terms of her writing, which has become inscrutable.

At the age of thirty five in Mexico she concluded that her “life in the world meant nothing. It wasn’t worth a handful of beans. In the annihilating force of the mushrooms, I could hold onto nothing of this existence, not even my name. So I let them go,” although mysteriously enough she remains Charlotte Du Cann. (“Writing in Transition” 4-5)

That letting go of existence is no mere metaphor or disavowal of flash. It is the embrace of mortality itself, and it is deflating to learn that she got there by reading Castaneda, that groovy guy beloved by poseurs of a certain age older than Du Cann herself. As she confesses, of all the ‘new-age’ works she then had been reading

“it was Castaneda’s account of his apprenticeship with the Yacqui seer don Juan in Mexico that spoke most urgently to me…. the assuming of responsibility, the letting go of self-pity and self-importance… and the concept of impeccability” whatever that is.

The mysticism all sounds vaguely catholic, right through the obsession with death. “Death is your advisor, don Juan advises Carlos Castaneda. We are all beings who are going to die… so you don’t have time for petty moods or failures.” (“Writing in Transition” 4)

Those passages about death first appeared during 1990 in 52 Flowers That Shook My World. Du Cann’s obsession continues. She reposted the passages in November 2021 and that September reposted an interview with “postactivist” and “recovering psychologist” Bayo Akomolafe that in turn had appeared in the Spring 2021 issue (number 19 believe it or not) of Dark Mountain devoted to “death loss and renewal.” The subject of the interview is his book about, according to Du Cann, “death, dying and change,” a “collective space of sanctuary where things can die and provide energy, or compost, for transformation.” (“52 Flowers” 7) Akomolafe in his own words appears substantially harder than that to pin down.

14. No sybarites please we’re self-righteous.

If doom is the inevitable outcome why not embrace the sybaritic? Because the sybaritic, Du Cann now insists, is unacceptably shallow, an “artificial parasitic life” in the “indulgent, acquisitive, objectifying world I lived and worked in.” (“52 Flowers” 4) No more dream homes or dream frocks, only bad dreams.

Dark Mountain advocates a return to the land in premodern but nonpaleolithic mode. Running water let alone hope for none: Homespun if not hair shirts for all. Altered if not sybaritic states, however, are acceptable, encouraged: Shrug at the fates after a day working the land, pour a drink and pop a pill or, in the case of Du Cann, peyote. Oblivion describes the condition that enables the right thinking defeatist to endure the prospect of oblivion.

Subsistence agriculture is the only avenue available to salvage something of the human presence on earth. In “Barn,” an essay from 2021 and elsewhere Du Cann obsesses over classical mythology, spiritual dearth and, an uncharacteristic instance of consistency, death. After Ithaca, also from 2021, “is about recovering our core relationships with the mythos and the more-than-human world, revolving around the Underworld tasks of Psyche.” (Sheaf 46)

“Barn” strikes a similar, plangent note. “Once,” Du Cann laments,

“we had stories that kept us close to the land, that told us about a spiritual and physical negotiation between the wild world and the domesticated crops that fed and maintained us. As civilisations broke those contracts in favour of control, enforced by patriarchal religions, science and industry, we are now bearing the consequences of a culture that has ignored the tasks set by the goddess of love and beauty…. Sometimes, as the fairytales and myths tell us, you only need the smallest of things to help you to change the course of destiny: an ant, a reed, an ear of tufted barley, a handful of coloured beans.” (Sheaf 12, 14)

However deranged her mashup of Greek mythology, new age mysticism and the currently obligatory jab at patriarchy may appear, at least Du Cann holds out the possibility of hope for humanity, in those passages if not always. It is a relief compared to Kingsnorth.

15. The comfort of despair.

“When I hear the word ‘hope’ these days,” Kingsnorth declares, “I reach for my whiskey bottle. It seems to me such a futile thing.” He is one of those people without moral imagination who spent years in miserable employment attempting but failing to win the approval of an overbearing parent. It was only the death of his father that freed Kingsnorth to live the Walden life which in turn however shackled him to his dogged and self-defeating despair.

His philosophy, reduced to its essence, amounts to a tantrum against the human condition. We are after all mortal, so each of our situations ultimately is as hopeless as Kingsnorth considers the prospect for humanity at large. But we do have the choice to snivel at the inevitable or do something, however daunting, for ourselves and our descendants, doomed as Kingsnorth hopes they may be. That is an aspirational accommodation he refuses to countenance for himself or anyone else despite protestations of concern for his children whom, he speculates, may “move to cities and become fashion designers…. That’s up to them:” An echo of the early Du Cann. But what of their own children who are, by his lights, unlikely to walk the planet?

In the meantime he endeavors “to walk a fine line between terrifying and depressing” the kids, a rather bleak balance. The flippant posture goes some way to contradict Kingsnorth’s insistence that the apocalypse is imminent but despite the strident style of his writing he also now insists that he does not presume to tell anyone what to do, his further abrogation of responsibility. (Wagner)

Although he has decamped from London to rural Ireland and a compost toilet, Kingsnorth exhibits some contradictory ecoconvictions. While disavowing modernity he assembles model trains for his children (Smith), an odd activity in context because the railroad could be considered an avatar of pollution, expanded trade and other developments that Dark Mountain decries. And how does he power his trains? Perhaps they operate at the electrified house of a neighbor.

If Dark Mountain sounds like a compact coterie of incoherent cranks, the movement continues to enjoy a certain respectability, in particular in its native United Kingdom.

16. A sort of antiestablishment establishment within the establishment.

Tate Britain, to cite a single example, has mounted a number of exhibitions created by members of the movement. One of them is part of its series of “Cooking Sections” within its “Art Now” program “showcasing emerging talent and highlighting new developments in British art.” The Dark Mountain show is called “Salmon: A Red Herring,” which “explores the deceptive reality of salmon as a colour and as a fish” and appeared in conjunction with a book of the same title and an essay on the subject called “Salmon Island” at the Dark Mountain blog.

The artists in question, Daniel Fernández Pascual and Alon Schwabe, actually address the subject of salmon farming and its attendant ecological infelicities off Skye, a practice worthy of censure, but in making the reach toward art the project as executed is by turns incomprehensible and callow.

“Salmon are at home in colour…. Salmon are a means by which colour moves through a logic of ingestion: salmon metabolise their colour, drawing life from it, and humans, craving this colour species, consume an image of health…. ”

Whatever any of this means at least it represents a respite from death. And salmon could color code themselves. “If salmon could peer inside their own bodies,” the text intones, “they could distinguish, from their muscle-tones, the Trondheim Fjord from the waters of Skye or the Bering Sea.” (“Salmon Island”)

Salmon after humans get at it.

Farmed salmon, if they also had auto-x-ray vision, could not manage the feat because they are not ‘salmon’ weighted with myth but rather deracinated ‘[salmon]’ as indicated by their description in brackets minus the adjective throughout the essay, the kind of cheap device beloved of pretentious middle school posers attempting to write with literary aplomb.

The conceit of “Red Herring” resembles a kind of shallow Fluxus without the playful sense of humor (Dark Mountain does not laugh), messy imagination or subversive surrealism. In the end “Red Herring” is neither art nor literature and has no place in a legitimate museum.

17. Enraged state of the art historians.

The selection of “Red Herring” for its august galleries in Pimlico reflects much about the state of Tate Britain. The state of the Tate is not good, as indicated by a recent Hogarth retrospective that, Jackie Wullschläger observes in the Weekend FT, amounts to “an instruction not to enjoy the paintings.”

The exhibition is a dreary example of the national self-loathing that infects a broad segment of English academia. According to the text that accompanies the paintings, “Hogarth’s freedom of opinion, his critical freedom, the freedom of his characters… might seem to be something always to defend.” “But,” Wullschläger warns, “no:” Instead Tate Britain goes on to serially denigrate everything Enlightenment, European or elite, an obsession that characterizes current conventional wisdom. “Enlightenment ideas” for example are hideously flawed because they

“were mainly produced by and benefitted white men from the middle and upper classes. The concept of European superiority deepened, entrenching ideas about nation, personal identity and racial difference, manifested in the horrors of transatlantic slavery.” (Wullschläger)

Leaving on one side the inconvenient fact that Enlightenment thought was profoundly and universally antislavery, although to its twenty first century critics the Enlightened aspiration to universal values itself consists of another crime, the pictures themselves depict something different. Hogarth was so radical, and his savage satire of high society so humane, that his work takes “a tightrope walk between critique and empathy.”

Prig that he was, George II refused Hogarth’s gift of “The March of the Guards to Finchley” because he believed it made a mockery of the British army. And so it did… and ultimately did not.

Wullschläger is brilliant on the layered social commentary of ‘the March.’ Hogarth depicts not only the “raucous tactility” of the eighteenth century but also its “democratising and economic forces that favoured bourgeois spectacle, blurring boundaries between the theatrical and the real.” He travels further down the social scale too, to celebrate “a middle and working class previously unacknowledged in British art,” in ‘the March’ and a raft of other paintings.

His “gorgeously individualised” group portrait of six servants (all of them white; this was eighteenth century London, an overwhelmingly white metropolis) might appear to the uninitiated as the humane, respectful and even affectionate depictions Wullschläger describes. According to Tate Britain that generous reading misses the invidious point: “Such apparently informal studies seem to suggest a new spirit of individualism, but inequities of race and social status persisted.”

Whether or not those inequities existed more generally they are absent from the picture, which should have been the focus of the curator, not a preoccupation with the shallow sociological vogue for universal (irony alert) oppression and victimhood.

By eerie coincidence the portraits do considerably more than “suggest a new spirit of individualism.” They celebrate that spirit and those individuals, and individual dignity; not necessarily so good. Individuality itself may present a problem to the pseudo-collectivist preachers of oppression. Whether or not that is the case, in their telling the otherwise intelligent appearing servants probably have been bought off by their wages and blinded by contentment to the point they do not realize they are oppressed.

18. Confident comedic chaos.

The jostling society that Hogarth records is absent from the commentary with which Tate Britain has saddled this dazzling work. His was, to take a term from Ruth Scurr and Penelope Corfield, an age of optimism.

In ‘The March,’ Wullschläger again, she is irresistible here, soldiers at the foreground of the painting mix with townspeople, “drinking, pissing, vomiting, stealing, brawling, flirting,” an “arabesque of heads--glinting helmets, old men’s wigs, baby’s bonnets, lopsided bicorns [tricorns would await the second half of the century], pugilists’ bald pates.”

All of life is out and about in Finchley and on the road to town, and all of it exudes a crazy confidence: “Hogarth’s boisterous Britain looks chaotic but knows where it is headed. Orderly troops march in the distance.” Even in the riotous town center, where a singer slaps away a Jacobite broadsheet and a “Union flag flutters,” a fractious nation celebrates itself. (Wullschläger) With an insight lost to Tate Britain, Hogarth understood that it was an astonishing time to be British.

After all, the inimitable Brigid Brophy, gifted as she was with “sheer artistic insolence,” understood that “the two most fascinating subjects in the universe are sex and the eighteenth century,” intimately and irrevocably intertwined as the topics remain. Hogarth understood that too. (Brophy; Corfield 98; Scholes; Scurr)

19. I contradict myself; I contain multitudes.

In common with a lot of zealots, Du Cann does not want for ego. Notwithstanding her description of it as shallow and parasitic, she appears untroubled, proud even, of her early work advocating a lifestyle antithetical to the ethos of Dark Mountain, obsessed as she was with all species of fashion and amused as her work is by transgression. Her online profile refers to her years in the fashion industry and cites Offal without opprobrium. In those sunnier days Du Cann celebrated the simple solaces of food along with the adultery and indulgence. “Tuck,” another story from Offal, describes the furtive feeling of comfort that a cake stolen from the kitchen after curfew offers a young girl stuck at boarding school. The school but not the girl is miserable.

An apparently timid boy abused by his cruel and conformist mother finds self sufficiency in smuggled sweets:

“It was dark in the room. Johnny was afraid of the dark. He lay very still so as not to disturb the wolves under his bed…. He smiled in the dark, and hugged himself. The grown-ups didn’t know anything about his secret. He didn’t care if his mother never stroked his hair or kissed him good night again. He hated her. He loved the chocolate now.” (Offal 62)

20. An eye for atmosphere.

The earlier Du Cann can have an eye for atmosphere. The satire of a New Fogey and his world (with misgivings; she appears to regret their falling out) describes an indelibly London look:

“He kept what he called his Old Look in a tiny exquisitely grubby part of London called Spitalfields…. It was a house that felt as though somebody had lived there a long time. [Nobody had.]…. He lived amongst artists and fellow critics who all decorated their houses with a scrupulous historical accuracy. All under the shadow of a perfect Hawksmoor church.” (Offal 47)

The Hawksmoor reference is to Christchurch Spitalfields, one of the great buildings in Europe. Its originality transcends ecclesiastical architecture, a powerful composition of giant orders, some classical and others unique to the imagination of Hawksmoor himself. The church is a structure so startling it contributes much to the conceit of Peter Ackroyd that the singular architect was a surreptitious Satanist.

Du Cann was writing when Spitalfields was even more atmospheric than it remains. Then ghosts walked the Huguenot precincts hard by Christchurch through a waft of danger, now with a waft of wealth. Even so the place remains exquisitely grubby, messy and vital despite the addition of fashionable restaurants and shops adjacent to the chaos of Brick Lane.

21. The barbarous kitchen.

The transition of Du Cann to sustainable culinary consumption has been both gradual and rational, if not the conclusion she eventually reaches. She quit eating meat after reading about slaughterhouse conditions; fish after reading about their lack of sustainability; unseasonal fruit after reading about the plight of African migrant laborers in Italian and Spanish hothouses. She foreswore supermarkets: “Somewhere a restaurant door slammed shut and an allotment gate clicked open,” although apparently not for long. (“Uncivilising the Kitchen”)

“In those grassroots community activism years,” Du Cann explains,

“we knew that growing radishes would not change the world but it would radically change our relationships with the earth and with each other…. It was a time when people on panels… prophesied that bio-tech loaves and fishes would feed the 9 billion.”

“But,” cue Dark Mountain, “something was missing. Everything I wrote had this evangelical tone.” (“Uncivilising the Kitchen;”emphasis original) Nobody, according to Dark Mountain, should promote anything biotechnical anymore that might feed the 9 billion. Beginning in 2018, Du Cann set about ‘uncivilising the kitchen’ instead, through the agency of “Dark Kitchen,” an addition to the Dark Mountain blog. It is not apparent just what she advocates. Elements of her new age mythological mashup including vague reference to Eros and Psyche are present along with the de rigeur Dark Mountain drumbeat of despair.

Exhortation is evil. It subverts resignation and the need to live in “austere restricted times,” while “neither knowledge nor social justice gives enough heft for people to change,” gnomic as that sounds. Instead, “an imaginative relationship with the physical world had to be created. Our hearts had to be kindled by something stronger, more alluring…. ”

If that sounds like the preamble to a plea for mindful living in harmony with ‘the mythos,’ the “thing you never thought of before” turns out to be something workaday instead, “seaweed for breakfast on a limestone beach in September.” That is a new agey enough sentiment but also appears devoid of mysticism and a bit muddled. One thing however is made as clear to her reader as it is to Du Cann. In the end like her life it amounts to a hill of beans: “Field beans have been grown here in Britain since the Iron Age and embody one of the uncivilised principles of the manifesto--being rooted in time and place.” (“Uncivilising the Kitchen”)

All, however, is not as rooted in British time and place as first appears. In an echo of Elizabeth David, that great culinary Anglophobe whose work had to have been among those thousands of Du Cann’s books, salvation resides instead “in the fragrant and spicey [sic] cuisines of the Middle East and other countries,” not in the traditional foods of Britain itself.

Leaving on one side the fact that Iron Age peoples themselves forged civilizations and that other crops are as equally rooted in time and place and rooted in places other than Britain as beans, certain difficulties are bound to arise if nations writ large follow the Dark Mountain lead.

The Dark Mountain Project biannual journal

22. We’ve got to destroy this village to save it.

The practical ramifications of Dark Mountain impracticality, of Du Cann decrying as she does any exhortation to “reduce our energy use! Get in season!” would be catastrophic. (“Uncivilising the Kitchen”) Dark Mountain, Kingsnorth and she may not care. “Humans,” Kingsnorth declares in his “Eight Principles of Uncivilisation,” “are not the point and purpose of the planet.”

On that point, and on his insistence to reject any notion that the “converging crises of our times can be reduced to ‘problems’ in need of technological or political ‘solutions,’” his detractors have pounced. (Resurgence) “For more conventional activists,” Daniel Smith writes at The New York Times with no small degree of understatement, “Dark Mountain’s insistence on remaining impractical can be not only disorienting but also irksome.”

George Monbiot, according to Smith “one of England’s most prominent environmental journalists,” engaged in an acrimonious debate with Kingsnorth at The Guardian during 2009 following publication of the Dark Mountain manifesto. Monbiot was appalled at the callous complacency of Kingsnorth and estimated that if his manifesto were adopted several billion people would die:

“How many people do you believe the world could support without either fossil fuels or or an equivalent investment in alternative energy? How many would survive without modern industrial civilization? Two billion? One billion?... And you tell me we have nothing to fear.” (Smith)

Kingsnorth was unmoved, “increasingly attracted” as he is “by the idea that there can be at least small pockets where life and character and beauty and meaning continue.” (Smith) That chilling species of reductive rationalization is inevitably elitist and whether or not intentional misanthropic. The billions may die but their demise masks a moral victory because morally superior composters carry on.

If we are living through the anthropocene, a valid question given the capacity of humans to overestimate their own significance both individually and collectively, a phenomenon Kingsnorth to his credit comprehends, then the better approach than leaving the planet and its people to a degraded fate may be attempting to wield our power for the commonweal despite the risk of unintended consequence.

23. Contrasting convictions from a common core.

Smith, it seems out of nowhere but perhaps because a documentary about Stewart Brand appeared during the previous year, makes tidy comparison to him and Kingsnorth even though it does not appear either of them has paid the least attention to the other.

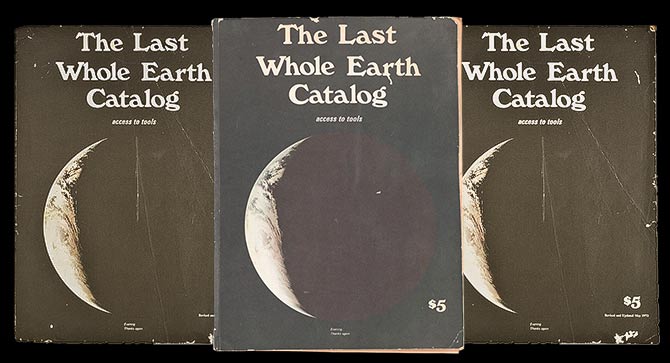

Brand, who among many other things anticipated the digital revolution and also published The Whole Earth Catalog from 1968 until 1971, was a visionary yet conservative icon of the counterculture and inspires any number of avaricious Silicon Valley acolytes, not much of a recommendation in itself.

Although Smith misquotes him, the title of the documentary also is Brand’s most famous utterance, his ‘mission statement’ from the Catalog, “We Are as Gods and Might as Well Get Good at It,” a perspective obviously anathema to Kingsworth. (Cadwalladr) Yet as the Catalogue indicates he and Brand have shared a few convictions.

The mission statement continues:

“So far remotely done power and glory--as via government, big business, formal education, church--has [sic] succeeded to the point where gross defects obscure actual gains. In response to this dilemma and to these gains a realm of intimate, personal power is developing--power of the individual to conduct his own education, find his own inspiration, shape his own environment, and share his adventure with whoever is interested.” (Gillespie)

Other than the reference to actual gains, the passage might have originated with Kingsnorth.

It can be difficult to recall how radical Brand was because

“so many of the ideas that first reached a mainstream audience in the Catalog--organic farming, solar power, recycling, wind power, desktop publishing, mountain bikes, midwife-assisted birth, female masturbation, computers, electronic synthesizers--are now simply part of our world, that the ones that didn’t go mainstream (communes being a prime example) rather stand out.”

So both of them believe in the grassroots, and on that note Kingsnorth supports the British withdrawal from the European Union. “There’s a green radical case,” he claims, “for leaving Europe” because the EU is a “huge, undemocratic bureaucracy trying to run thirty countries from one city. I’m instinctively in favour of small groups running their own affairs, close to the ground. Democracy only works when it’s close to the people.” (Wagner) That sentiment too would resonate with Brand.

As a pertinent aside the point about local democracy may be fair but in itself hardly furthers any ‘green case’ and the NIMBY types sometimes openly attempt to prevent the intrusion of environmental assets such as wind farms.

Kingsnorth and Brand both prize autodidacts, individual responsibility, local autonomy and, in Brand’s case, especially local institutional government. He was an early advocate of the organic agriculture and small scale farming; Kingsnorth would find common ground there.

Brand’s belief in consumption as a creative, liberating force however would appall Dark Mountain. There in the Catalog amidst the lifestyle choices appear those mountain bikes and synthesizers along with down jackets, kayaks and more: L.L. Bean was an inspiration. Along with its microhumanism “the Catalog was,” as Fred Turner has noted, “‘deeply consumerist.’” (Cadwalladr)

24. Existential options.

Both theoretical antagonists recognize the existential threat of climate change but their reactions to the problem diverge. “For Kingsnorth,” as Smith explains,

“the notion that technology will stave off the most catastrophic effects of global warming is not just wrong, it’s repellant--a distortion of the proper relationship between humans and the natural world.” (Smith)

The contrast with Brand could not be more acute. It is the choice between medieval scholasticism and the empirical Enlightenment, for he is an apostle of optimism as well as consumption. The reference is explicit. Brand modeled the Catalog on

“Diderot and his Encyclopédie and this Enlightenment idea that basically knowledge had been held back by the aristocrats and all the rest. The whole thing was to keep people from knowing how to do things.”

If science in general was the Enlightenment faith, technology in particular has become Brand’s. The potential of genetic modification of crops and species, of nuclear power and urban density to combat climate change fascinate him. “I think whatever happens, he told The New Yorker in 2018, “most of life will keep going. The degree to which it’s a nuisance--the degree to which it is an absolutely horrifying, unrelenting problem is what’s being negotiated.”

Brand believes with justification “that civilization is revving itself into a pathologically short attention span,” which among other deleterious things discounts progress. (Kehe) To combat the malady Brand’s principal endeavor since 2018 has been the nonprofit Long Term Now Foundation dedicated to the promotion of “long term thinking” about climate change and other challenges. (Wiener)

A sense of history that includes rejecting short term thought and reference to the anthropologist Steven Pinker, derided now by the left for his refusal to wallow in the trope of oppression, fuels Brand’s optimism and, Kingsnorth should cover his ears, hope for humanity:

“It’s been a long hard slog for women. It’s been a long hard slog for people of color. There’s a long way to go. And yet you can be surprised by successes. Gay marriage was unthinkable, and then it was the norm. In-vitro fertilization was unthinkable, and then a week later it was the norm. Part of the comfort of the Long Now perspective, and Steven Pinker has done a good job of spelling this out, is how far we’ve come. Aggregate success is astonishing.” (Wiener)

Which, to paraphrase Moll Flanders, would you choose, constructive hope for better lives or the Dark obsession with death and despair?

25. In the end there is only us, along, perhaps, with a warming fire.

Du Cann is nothing if not as obsessive as Kingsnorth, but in trading high society for Uncivilization only has embraced a new form of fashion contrapuntal to the old Vogue style. Who can know: She may assume a third incarnation. Whatever her future, the predilection to Nudity may be last to go, the constant in an inconstant life. “Clothing,” she claims in Dirty Weekend, “is the beginning of inference,” and for Du Cann these days, at least by her lights, unadorned honesty will out. (Dirty Weekend 31)

Whatever she does, Nudity would remain a Dark Mountain bonus. It costs and consumes nothing other than an admittedly carbonized heat source or heap of crudely tanned sheepskins, but only during wintry months.

***

Recipes for roast beef and oysters, separately and combined, and for beans, appear in the practical, along with dishes derived from St John Bread and Wine in Spitalfields.

Further commentary on Tate Britain and Hogarth appears, appropriately, at the Wall of Shame.

Sources:

Anon., “Art Now Cooking Sections, Salmon: A Red Herring,” 27 November 2020 - 30 August 2021, https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-britain/exhibition/cooking-sections (n.d.) (accessed 5 February 2022)

Brigid Brophy, “Mersey Sound, 1750,” The New Statesman (15 November 1963)

Carole Cadwalladr, “Stewart Brand’s Whole Earth Catalog, the book that changed the world,” The Observer (5 May 2013)

Penelope Corfield, The Georgians: The Deeds and Misdeeds of 18th century Britain (London and New Haven 2022)

Charlotte Du Cann, “52 Flowers that Shook My World,” Writing in Transition (November 2021)

“Barn,” Sheaf (Summer 2021)

“Benchmarks or Why I Don’t Read Like I Used to,” Writing in Transition (August 2011)

The Dirty Weekend Book (London 1984)

A Guide to London’s Best Shops (London 1982)

Offal and the New Brutalism: A Book About Food (London 1985)

“Uncivilising the Table,” Dark Mountain, https://dark-mountain.net/dark-kitchen-uncivilising-the-table/ (5 April 2018) (accessed 16 December 2021)

Vogue Modern Style: How to Achieve It (London 1988)

Nick Gillespie, “We Are as Gods and Might as Well Get Good at It,” Reason, https://reason.com/2018/11/04/we-are-as-gods-and-might-as-we/ (4 November 2018) (accessed 3 February 2022)

Jason Kehe, “The Backward-Looking Futurism of Stewart Brand,” Wired (17 March 2021)

Paul Kingsnorth, “The Dark Mountain Project,” Resurgence & Ecologist Issue 263 (Nov/Dec 2010)

“Uncivilisation,” https://www.paulkingsnorth.net/unciv (n.d.) (accessed 16 December 2021)

Tuppy Owens, The Sex Maniac’s Bible (London 1972 and annual editions through 1995)

The 1992 Sex Maniac’s Diary (London 1992)

Howard Jay Rubin, “Picturing The Earth: An Interview With Stewart Brand,” The Sun Magazine, https://www.thesunmagazine.org/issues/92/picturing-the-earth (July 1983) (accessed 5 February 2022)

Lucy Scholes, “The Snow Ball by Brigid Brophy review--a swirling, sensual feast,” The Guardian (4 December 2020)

Ruth Scurr, “Age of Optimism,” Weekend FT (5-6 February 2022)

Daniel Smith, “It’s the End of the World as We Know It… and He Feels Fine,” The New York Times (17 April 2014)

Edward Ullendorff, “The Bawdy Bible,” Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies vol. 42 no. 3 (1979) 425-56

Erica Wagner, “The constant gardener,” The New Statesman (30 June 2016)

Anna Wiener, “The Complicated Legacy of Stewart Brand’s ‘Whole Earth Catalog,’” The New Yorker (16 November 2018)

Jackie Wullschläger, “A brake on Hogarth’s progress,” Weekend FT (6-7 November 2021)