Unsung icon: Elisabeth Ayrton & English mores within & beyond the kitchen.

An unauthorized version of this essay containing distortions, inaccuracies and infelicitous language appeared recently in two installments at the journal Repast. Do not read them. Instead, read the accurate version as its author intended it here at the lyrical.

1. An introduction to England.

It is 1982 in the United States. “This book,” a sheepish pair of reviewers discloses, “has been an eyeopener to us.” The book is English Provincial Cooking by Elisabeth Ayrton, the scholars Claudia and Walter Cowan writing in The Virginia Quarterly Review. Their unfamiliarity with the foodways of England, surprising as it ought to have been given the historical record, was by no means atypical of Americans then and for the most part is not now. (“Cookbooks” 138)

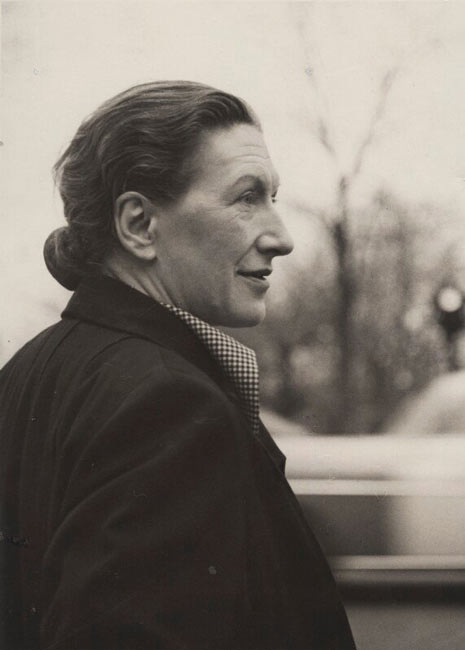

Mrs. Ayrton, at home.

2. A neglected polymath.The Cowans explain that “Mrs. Ayrton is a cook, an antique dealer and a professional writer,” which is something like describing William Blake as a cantankerous and dysfunctional eccentric, true enough but misleading by omission. Mrs. Ayrton does not enjoy the rarefied reputation or army of acolytes that reveres her contemporaries Elizabeth David, Jane Grigson and, to a lesser extent, Theodora FitzGibbon, who does however have a cultic following in Ireland. That historical anomaly requires rectification.

Hers was an eventful life. The child of journalists--her father also wrote popular bodice rippers that earned a handsome income--the future Mrs. Ayrton escaped their unhappy home with relief when she went up to Cambridge in 1929, where she earned a degree in both English and archaeological anthropology. (ODNB)

Mrs. Ayrton (as she invariably refers to herself in print) would employ both her fields of study at Cambridge to exemplary effect. She wrote four novels, a number of short stories, advertising copy for J. Walter Thompson, numerous articles on travel and food for magazines including Harper’s Bazaar and Vogue, poetry that the BBC broadcast, contributions to its Woman’s Hour program and, in 1961, Doric Temples, a scholarly study of the form replete with elevations, floorplans and photographs.

A passage at its outset provides a good example of her precise prose and acute insight. It is a meditation on the essence of the classical idiom with an allusion to Homer:

“If you build to catch your gods and hold them with the sheer strength and perfection of your architecture, then the long-fingered shadow of a column is as powerful for the purpose as the great strength of the stone which throws it. The quiet strength of the stone is very great and the patterns it makes with its shadows are infinite and irresistible because of their mathematical exactitude and perfection.” (Doric Temple ix)

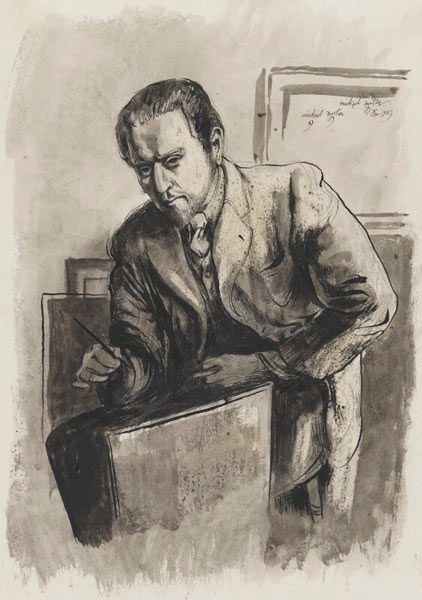

Despite the prodigious output, none of it came easy to her. Invidious as it is to discuss anyone, especially, these days, a woman, by reference to a man, it is essential to note that Michael Ayrton was not only her muse but also her champion.

3. Another, less neglected, polymath--and muse.

For nine years until 1953 Ayrton lived on the border of Fitzrovia and lived the Fitzrovian life. He ran and argued with its wild boozy artists, writers and louche hangers on, although he never engaged in the excessive alcoholic binges the majority of them relished.

“Like Wyndham Lewis, whom he greatly admired, Ayrton,” writes Michael Bakewell,

“prided himself on his breadth of talents: painter, sculptor, poet, novelist, maze-maker, mythologist, occultist and a member of the BBC Brains Trust.”

This learned polymath was an autodidact. Expelled from school at the age of fourteen for seducing his French teacher, the universally precocious Ayrton never returned. (Michael Ayrton 20)

His accomplished acquaintances considered him “[a]n amazingly varied man” but not a congenial one, not early in life anyway: “In his early years Ayrton was notorious for a certain belligerent and uncompromising arrogance.” His biographer describes the younger Ayrton’s “air of… irritating self-possession” and “conceit.” (Michael Ayrton 25) While working with him for the set and costume design for MacBeth in 1941, Gielgud castigated him for his “ungraciousness of manner and lack of charm.”

Again according to Bakewell, “Ayrton did not suffer fools gladly and took pleasure in stirring up controversy.” A notorious 1945 public diatribe against Picasso (“a vast erection of bones in the graveyard of expression”) drew widespread ire and prompted Robert Colquhoun, himself an esteemed painter heavily influenced by Picasso and otherwise a friend of Ayrton, to attack him in turn as “positively the enemy of painting.” (Bakewell 40)

This uncompromising man who refused to suffer fools found Elisabeth entrancing from their first meeting and became her husband in 1952.

Ayrton by Ayrton.

4. More malaise.Her second one that is. She met the first, Nigel Balchin, as an undergraduate at Cambridge and had married him in 1933. Now like the Ayrtons for the most part forgotten, Balchin was an admired novelist who addressed the wrenching topics of trying times for England.

Darkness Falls from the Air, for example, investigates behavior, much of it bad, during the London blitz. Its “world-weary” narrator, based on Balchin himself and the time he spent as a temporary civil servant at Lord Woolton’s usually lauded Ministry of Food, finds himself enmeshed at another wartime ministry in a tangle of “vested interests, careerism, jockeying for position and Machiavellian intrigue.”

Balchin sets the selfish maneuvering against the background of a London where prostitutes (a lifelong source of fascination for him; he also had a fetish for spanking) loiter in doorways as firebombs fall and the narrator’s wife carries on an affair with his colleague. (Collett 122, 36-37) Among the admirers of Darkness Falls are Clive James and the peerless Elizabeth Bowen, whose own wartime novels are better, and indeed peerless.

The Balchins had three daughters and the marriage survived for fifteen years, a remarkable run given the circumstances. Balchin was haunted by a “pervasive insecurity” and his otherwise sympathetic biographer refers to his subject’s “overbearing personality.” (Michael Ayrton 143; Collett 237) He was by any measure a cad, a bad spouse and diffident father. A hypocrite of staggering magnitude, he insisted on an open marriage and badgered his wife to take her own extramarital lovers. When she finally capitulated his reaction was rage. (Collett 127)

Throughout his life Balchin adhered with unwavering insistence to the sexism of his time. Nobody suffered the consequences more than his first wife. During the 1930s she worked tirelessly as his secretary: Balchin himself admitted in his journal at the time that “wife, red-haired Cambridge graduate… does all the work.” (Collett 93)

Her devotion was not reciprocated. Although Elisabeth tried her hand at writing, Balchin thought her a bad writer “and was dismissive of her efforts.” (Collett 160) Understandably enough she became so discouraged she gave it up, which may have been Balchin’s intention given all the work he expected her to do for him instead. (Collett 237)

Oblivious as he was to his wife’s intellect, Balchin could be oddly introspective. He had no inner equanimity. (Michael Ayrton 143) An entry from his journal immediately after the collapse of his marriage to Elisabeth (he would take up with a woman twenty one years younger within weeks) sounds self lacerating,

“I had allowed my life to become grey and stodgy. I had lost my zest & I had fallen back on a sort of dull, cold goodness with mighty little in it of real love or warmth.” (Collett 237)

It is hard to reconcile his self-justifying claim to ‘goodness’ with the other character traits he catalogs: His household must have been claustrophobic for the entire family.

Although Michael Ayrton’s biographer maintains with some justification that “in some ways” Balchin “knew his wife very well” because he had written to her with insight that “you are a very generous person in all things, and you have very little sense of conventional shame… you give harder and nearer the bone to people you like than anyone you know,” he never appreciated her intellect. (Hopkins 153)

5. An unaccountably underrated figure.

As inconceivable as that sounds at a remove, Balchin was not alone. Elisabeth was so painfully shy and lacking confidence that she armored herself with “a reserve which caused many people to underrate both her intelligence and her passionate nature.” Still it remains astonishing that Balchin was so selfcentric that he “had continued to mistake them through fifteen years of marriage.” (Hopkins 143)

He perpetuated that ‘mistake’ even though Elisabeth had held a position of considerable authority and significance during the Second World War. At the Special Operations Executive that dropped agents into Occupied France on espionage and sabotage missions she managed a staff of thirty five responsible for screening and selecting recruits. (Collett 159; ODNB) Once the war ended they moved to the country and Balchin “expected her to be a fulltime house wife,” an enforced passivity she hated after the arduous excitement of her wartime work. (Collett 160; Michael Ayrton 146)

6. Mutual transformation.

Enter Ayrton. Elisabeth met him at the insistence of Balchin, who had been lusting for Joan Walsh, Ayrton’s lover at the time. (Collett 227) The four became fast friends despite Ayrton’s age; he was eleven years younger than the Balchins. During a visit to Paris, Balchin engineered the casual swap of sexual partners that would end his first marriage.

Balchin should have known that the “quartet, with its paradoxical parity of immoral morality,” could not last. Elisabeth Ayrton “did not share her husband’s taste for short-term sexual liaisons.” (Collett 125) Unlike him, if she did fall far enough to sleep with someone, she fell hard.

Notwithstanding an obsession with sex and sexual conquest, it appears Balchin was bad in bed. He wrote of his marriage to Elisabeth that “he felt himself to be sexually unacceptable” and Penelope Leach, one of the Balchins’ daughters and a formidable figure in her own right, told his biographer,

“if somebody has an affair that then turns into a passionate marriage it’s reasonable to assume that Nigel and Lis’s sex life wasn’t wonderful.” (Collett 238)

In his treatment of her Ayrton was in all but one way the Antibalchin. “Ayrton treated her as an individual and enabled a woman distinguished… by shyness and lack of self-confidence to emerge from her shell. He was also prepared to entertain the Newnham graduate as an intellectual equal.” (Collett 236-37 quoting Michael Ayrton)

Ayrton lifted an emotional siege. “It was,” explains Dr. Leach,

“really because he loved her so much. She became a completely different person and it was very exciting to see. She began to write, she began to giggle.” (Collett 238)

Ayrton not only encouraged her to write but also illustrated some of her work and asked her to edit his own, which could be extravagantly self-indulgent; “although a strict critic, she was also a sympathetic one.” (Michael Ayrton 280, 185)

She did much more for him than edit his writing. If he brought her out of the creative wilderness, she transformed his personality, the scope of his already extensive artistic endeavors and the depth of his intellectual inquiries. She also made him, perhaps for the first time, personable. Following their marriage “it became clear that Elisabeth’s husband was not the half-admired, half-resented prodigy that London thought it knew.” (Michael Ayrton 175)

“Elisabeth,” Ayrton’s biographer maintains,

“provided everything he needed to complete his complex transition form enfant terrible to mature artist. She was in every way a revelation to him--as a sexual partner, intellectual companion and as a mother…. ” (Michael Ayrton 171)

Her longstanding interests in archaeology, history and poetry began for the first time to inform his work. In a reversal of the standard trope, his step-daughters adored him and resented Balchin. (Michael Ayrton 157)

None of this should imply that the Ayrton house amounted to domestic utopia. If, as Hume believed, truth springs from argument among friends, then the Ayrtons refused to dissemble. The couple engaged in epic fights, some of them counterintuitively constructive:

“Through more than twenty years of marriage they continued to quarrel ferociously at intervals, partly because they were two forceful and passionate personalities who inevitably did not always agree, and who expressed their disagreements vehemently, but also simply because they enjoyed it: each was the other’s favourite sparring partner, and they would argue furiously in the happy knowledge that basically they were mutually satisfied and compatible.” (Michael Ayrton 188)

7. Elephants in the bedrooms.

Satisfied and compatible, but with a colossal and corrosive exception; like Balchin, Ayrton conducted both open and clandestine affairs, from one night stands to long-term liaisons lasting as long as four years, for the duration of his marriage to Elisabeth. (Michael Ayrton 188-90, 305)

She hated the promiscuity but, generous to a fault, attempted to understand his rationale for the compulsion. In an interview with her granddaughter long after Ayrton’s death, Elisabeth explained:

“Michael believed, or felt very strongly, that lots of going to bed with people was a part of your creative strength and ability. If you couldn’t fuck then probably you couldn’t draw or paint or work at all. If you didn’t, then probably you couldn’t write or paint or anything as well as you might.”

One element of her hopeful attempt to accept his behavior itself provides an indication that their opinions often differed: “Picasso had exactly the same belief.” (Michael Ayrton 307)

The belief in a linkage between sexual promiscuity and creative accomplishment was neither unusual among artistic Britons of the age nor confined to men. Bowen among other women believed much the same thing, associating what one of her biographers delicately calls “her… extreme capacity with love… with her gift as a writer.”

During her long sexless marriage Bowen engaged in a succession of affairs ranging in length from a single night to as many as six years with both male and female lovers. One of them, May Sarton, wrote that Bowen believed it possible to “engage in extramarital affairs and keep one’s dignity and one’s personal truth intact, without hurting one’s life partner.” Bowen’s biographer notes with a drop of acid that the writer, “who was often judgmental about the conduct of her friends, condoned her own behavior.” (Feigel 171; see 162-72) That behavior extended to spying on her fellow Irishmen for MI6.

Out of this culture of emotional instability and sometime chaos also arose the work of Elisabeth Ayrton.

Elizabeth Bowen

8. A good nature and the nature of things.Mrs. Ayrton’s ability to tolerate the cruel and humiliating side of her husband is not entirely unsurprising given her remarkable character. By all accounts she was selfless and tolerant to an astonishing degree. Not even Balchin has anything bad to say about her. He and the Ayrtons remained friends; throughout his life she continued to worry, with justification, about his peace of mind, or lack of it.

Dr. Leach recalls her mother as “just very devoted, interested, intelligent, warm.” (Collett 126) Michael Ayrton’s biographer adds that

“Elisabeth was one of the rare people who are completely free from meanness…. She had a total contempt for money kept for its own sake, and a boundless optimism as to its continued supply for the really important things.” (Michael Ayrton 188)

“She could,” according to her entry in the often clinical Dictionary of National Biography,

“be alarmingly aloof on occasion, especially when inwardly intimidated; but when at ease she was warm [there it is again], charming, and profoundly interested in people. She was an atheist and lifelong socialist, with a firm belief that people should have what they needed; she was also unstintingly generous, and always preferred giving to receiving.” (ODNB)

Her fundamental decency came at some cost. “She could,” the DNB entry continues in its unmistakable cadence and notwithstanding her enviable output, “perhaps, have written more, but her diverse life, thoroughly enjoyed, enriched others as much as herself.”

9. ‘Come on in my kitchen... ’

Although Mrs. Ayrton had found domesticity with Balchin intolerable, that changed after 1952. “Living with Ayrton, she had become interested in cooking, from which came Good Simple Cookery,” in 1958. It was her first of several cookbooks, and if not devoted to British cuisine per se many of its techniques and recipes bear an unmistakably British cast; a pair of steak and kidney puddings and other steamed savory puddings; roast chicken with bread sauce, boiled lamb with caper sauce, many others.

Rationing had finally ended but taken a toll. A generation of women (for then the preponderance of home cooks were women) had lost the means, including basic ingredients, to learn how to cook or found themselves without domestic help for the first time. Good Simple Cookery therefore answered an acute need, would become a classic, at least in the United Kingdom, “and remains among the best basic cookery books.” (ODNB)

10… and back to a lost cuisine.

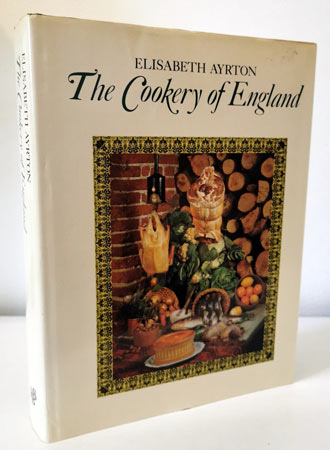

With The Cookery of England in 1974 Mrs. Ayrton dropped any pretense to internationalism. It is a comprehensive meditation on the English culinary canon, the subsequent Provincial Cooking its coda. The Cookery of England was in its way, or in two ways, epochal. First, her treatment of the subject recognized the English tradition as a cuisine worthy of serious consideration and revival. Second, as Justine Hopkins maintains, Mrs. Ayrton had introduced “a virtually new genre, the historical cookery book.” It sets

“concise, easy-to-follow recipes against a cultural background stretching from the fifteenth century to the present day, meticulously researched and engagingly presented.” (ODNB)

In common with Doric Temples, her writing throughout The Cookery of England is nearly mathematical in its precision.

Its sources are impeccable, and include four unpublished kitchen manuscripts handwritten during the extended eighteenth century from the reign of William and Mary to the death of Victoria in 1837. It was an era of creativity and consolidation for English foodways. “The period,” Sarah Gillies concludes,

“witnessed substantial changes in cookery and ways of dining and produced a literature on these subjects dramatically more diverse and detailed than at any previous time.” (Gillies 74)

In other words the era produced the bedrock national cuisine of Britain.

As Hopkins infers, Mrs. Ayrton wears her erudition with a diaphanous touch. A sly scholarship is evident from the outset of The Cookery of England, where its full title goes on to parody the obligatory eighteenth century overload of promotional detail;

“being a Collection of Recipes for Traditional Dishes of All Kinds from the Fifteenth Century to the Present Day, with Notes on their Social and Culinary Background.”

Those notes distinguish The Cookery of England from her more celebrated culinary contemporaries and Mrs. Ayrton’s work has held up well. At the 1990 meeting of the annual Oxford Symposium on Food and Cookery, for example, Lisa Chaney (biographer of Elizabeth David) and Harlan Walker recommended

“the delightful and scholarly Cookery of England by Elisabeth Ayrton, a book which has done more than most to increase our knowledge of English food.” (Chaney & Walker 226)

11. Forges and fortunes of war.

During the last couple of decades it has become a truism among historians that to create national unity and, in Britain, to forge a national identity from its constituent countries, a people require a foil.

Linda Colley for example maintains that a unitary ‘British’ identity following the Act of Union in 1707 became possible only through opposition to another, or more insistently a contrast with ‘the’ other. According to the Colley thesis Catholics as opposed to Protestants in general and French as opposed to the emergent British identity in particular provided the particular targets.

This focus on such limited causation may appear narrow, even reductionist, but no matter: Her 1994 publication Britons: Forging the Nation, 1707-1837, widely is considered the spiritual template for historians addressing other subjects as well, not only nationalism but also culture, colonialism, imperialism, militarism and racism among other things.

Culinary historians, ordinarily late to the historiographical table, anticipated the trend by applying the concept to foodways as a source of national identity, casting virtuous or otherwise superior ‘national’ dishes in opposition to inferior and variously ‘crude,’ ‘effete’ ‘enfeebling’ or ‘foreign’ foods, and at certain times in certain places there is much to recommend the line of analysis.

Thirteen years before Gillies and twenty before Colley, Mrs. Ayrton had framed the culinary rivalry between England and France as a war. Mrs. Ayrton, however, takes a lighter tone than historians of the Colley school in tracing the Anglo-French competition. “War was declared,” she says,

“between the English and French over the matter of the fine art of good cooking long before the Middle Ages, and though by the nineteenth century the English were certainly the losers and accepted the French as victors, the war still renews itself from time to time over the years.”

12. The literary front.

Mrs. Ayrton discerns a literary battle within the culinary war. French skirmishers scored some hits in the battle. The most famous may be Proust and his madeleines but he also addressed other foods including asparagus. According to literary critic and champion of the humanities Arnold Weinstein, the stalk Proust describes is an erotically charged emblem.

To cite but two other examples, Balzac was a prodigious gourmand who describes dining in any number of passages. And with The Belly of Paris Zola wrote his stinging critique of French politics and society through a parable of food and its vendors, contrasting the fat and the thin, the prosperous and impoverished situated in Les Halles, the ancient Paris market.

British forces, however, overwhelmed their literary rivals through five centuries of conceptual combat. “In memoirs, letters and novels,” Mrs. Ayrton explains,

“the meals described by Pepys, DeFoe, Smollett [especially, she might have said, Smollett], Thackeray, Charles Lamb, Charles Dickens and Dr. Johnson are irresistible…. From Chaucer onwards, great English writers have found the food of England worth serious mention, a delight and an inspiration to all right-minded men.” (Cookery of England 5)

13. Back to the barricades, or, a tale of two cities.

These guys.

The latest round of renewed rivalry on the culinary front was recorded in some detail by an unlikely Francophile. Although Mrs. Ayrton and her three contemporaries had engineered a revival of sorts two decades earlier, nearly nobody noticed, at least not in the United States and by no means in France, as the incredulity of the Cowens at the contents of English Provincial Cooking indicates.

During 1997, Adam Gopnik captioned an essay in The New Yorker with the rhetorical question “Is There a Crisis in French Cooking?” subtitled “What happened?”

With apparent reluctance and some reservations Gopnik concluded there was, although at the time Paris remained his favorite place to dine. “Now,” he reported,

“for the first time in several hundred years, a lot of people who live in France are worried about French cooking, and so are a lot of people who don’t.”

“The fear,” he continued in reference to the French, “is that the muse of cooking has migrated across the ocean…. ” Gopnik registered no surprise that she had gone to Berkeley or New York but was taken aback about the journey to “of all places, Great Britain” where “the only thing you wanted to do with the national culinary tradition was lose it.”

Like that last barb much of what Gopnik writes about in the essay is, as usual, wrong, but he did identify an inflection point that dropped France from the pinnacle of national cuisines during the early nineties. A year before Gopnik, Le Monde had expressed alarm at “la crise” in the state of French food.

Two years before Le Monde a portent appeared, the fastidious if overworked traditional cooking of Gary Rhodes at the Greenhouse in Mayfair had become sufficiently fashionable around London to win him a BBC series and cookbook, Rhodes Around Britain.

“People in London,” Gopnik himself noted in the clunking style that characterizes the nonfiction of The New Yorker,

“will even tell you, flatly, that the cooking there is now the best in the world, and they will publish this thought as though it were a statement of fact, and as though the steamed hamburger and the stiff fish had been made long ago in another country. Two of the best chefs in the London cooking renaissance said to a reporter not long ago that London… is one of the capitals of good food, and that the food in Paris--‘heavy, lazy and lacking in imagination’--is now among the worst in the world.” (Gopnik)

Gopnik fails to identify either the chefs or the reporter so we do not know what kind of food they cooked and discussed but his reference to a renaissance, if his usage is proper, infers that something in the British national cuisine may be worth keeping. A renaissance is after all renewal rather than revolution.

14. To paraphrase M. Python, nobody expects the Armenian-Italian deconstruction.

Gopnik cites Eugenio Donato, who “wandered from one American university to another--the Johnny Appleseed or Typhoid Mary of deconstruction, depending on your point of view.” Donato considers the blip that was la nouvelle cuisine as a “reformation” that failed to sustain itself because “a reformation points forward and backward at the same time. A revolution,” he maintained, “can sweep clean” but reformation by its nature is fleeting.

Elsewhere Gopnik maintains that the failure of nouvelle cuisine to evolve into something sustainable

“lies in the French genius for laying the intellectual foundations for a revolution that takes place elsewhere…. The Enlightenment took place here, and the Revolution worked out better somewhere else.” (Gopnik)

All this is preposterous and not only in its proliferation of conflicting metaphors about disparate intellectual and political movements. A renaissance is not a revolution and reformations can, and have, endured.

The strange selection of the obscure, abstruse Donato as analyst of culinary history comes across as if it were a whim, something like the tendency of Donald Trump to adopt the position of his latest interlocutor and Gopnik, it transpires, had been dining with Donato in Paris while writing the essay.

The Enlightenment was by no means exclusive to France: Volumes are devoted, properly so, to the English, German, North American, Scottish and other national clusters of humanist genius that blossomed during the eighteenth century.

The genius of the British culinary renaissance lies precisely in the ability of its cooks to look both forward and back; the same may be said about the explosion of creativity out of kitchens in the American south and other global regions. And it is unclear how ‘sweeping clean’ its heritage ipso facto improves the quality and sustains the appeal of a cuisine.

15. The endurance of anxiety.

Whatever the merit of his interpretation, Gopnik is influential and the notion that French food has suffered an agony of eclipse would become an evergreen. The New York Times Magazine published an article entitled “Can Anyone Save French Food?” In it Michael Steinberger echoes the unnamed chefs that Gopnik cites: “Since the late 1990s, Paris has come to be regarded as a dull, predictable food city. The real excitement is in London” and elsewhere.

Steinberger, however, found hope for Paris in the guise of “an unexpected source: Young foreign chefs,” among them the English one manning the kitchen at a place called Albion, each fact an unthinkable notion in the Paris of only a few years ago. (Steinberger)

In 2018, Vice published an article called “French Food Actually Sucks Now, Says Head of French Tourism Council.” Just last year The Guardian added its own eulogy and path to resurrection. In “The Rise and Fall of French Cuisine” Wendell Steavenson asks whether “a new school of traditionalists” will “revive its glories,” not quite the same thing as sweeping away the past.

Steavenson identifies the same saviors as Steinberger,

“a younger generation of chefs… now establishing themselves in French kitchens. Increasingly, they have trained in restaurants in London, New York, Copenhagen or Barcelona.”

“Back to basics,” Steavenson observes, “is proving popular.”

16. Back, or on, to the basics; only the basics.

The revival of British culinary fortunes that erupted during the 1990s did not rely on food alone. Foodways themselves, the culture and circumstance related to cooking and eating, played a prominent part. With the establishment of St. John in 1994 Fergus Henderson may have launched the bombshells on both fronts that won the war.

For now, however, another foil; Gopnik regards Le Grand Véfour in Paris as the most beautiful restaurant in the world and an exemplar of the French “cosmopolitan style.” It dates to 1784, was refurbished early in the nineteenth century and is nothing if not ornate, a stately, square high ceilinged riot of gilt framing and brass trim, chandeliers, pastoral murals, scarlet banquets upholstered in velvet, cut flowers and cut glass. (Gopnik; “Grand Véfour”)

Other than a service of caviar every dish is equally ornate and priced to match; examples include a starter, “Whole cooked foie gras terrine, artichoke and pear with fenugreek, pomegranate seeds;” a main, “Roasted Lozère lamb filet, yellow and red beetroot and Collioure anchovies, goat cheese with lemon zest;” and a dessert, “Artichoke ‘crème brûlée,’ candied vegetables, bitter almond sherbet.” (“Grand Véfour”) Scandal ensued when the place lost its third Michelin star a few years back but Le Grand Véfour remains a mainstay of the Parisian dining establishment.

Across the Channel at St. John, the contrast could not be more acute. The idiosyncratic restaurant, located in a narrow former smokehouse and then headquarters of the defunct Marxism Today with whitewashed walls, utilitarian flooring and plain wooden chairs, has since its foundation in 1994 adhered to five rules: “No music, no art, no garnishes, no flowers, no service charge.” “No seared salmon, no chicken, no crowd-pleasing side orders” either; no pandering, no preening, little pretense other than its studied disdain for pretense.

This unlikely legend is the most influential restaurant in Britain. What they do serve is fairly simple and famously crafted from ‘nose to tail;’ roast marrowbones with parsley salad and toast; boiled ox tongue; Eccles cakes; and Welsh rabbit (no savories at Le Grand Véfour or in France for that matter).

“This,” according to The Guardian, is

“resolute, timeless cooking; good, seasonal and served with a certain amount of solemnity by helpful people in long, white aprons. It was puritan, but it was generous, too.” (Cooke)

As Henderson and his partner, Trevor Gulliver, comment in typically wry terms within The Book of St. John, the title of course an irreverent and welcome reference to the bible:

“When we opened St. John we were accused of being 200 years out of date, which we took as a great compliment. While people were initially intrepid, eventually some began cooking the same way. Oddly though, we have found that tripe has not caught on in quite the same way as bones.

Trends are a tragedy in food--they condemn the sublime to the temporary; or they elevate the flimsy beyond its merit. Good things should be a constant and cooked with conviction.” (St. John 142)

The food of St. John is, as the subtitle of the restaurant’s first cookbook proclaims, “A Kind of British Cooking” and its attitude has taken the world, if not popular perceptions in the United States, by storm. (Nose to Tail)

The apparent simplicity and timelessness of the cooking is deceptive. Henderson and his successors in the kitchen amplify rather than ape the English tradition. An example from their third cookbook; “Butter bean, Rosemary and Garlic Wuzz.” Those ingredients are all traditional mainstays of the English kitchen (yes, garlic; Mrs. Glasse and her forebears use garlic) but not as wuzz, which, The Book of St. John is helpful enough to explain, “is onomatopoeic--it is self-explanatory in the same way that one does not need to explain a chop.” (St. John 138)

Another example of amplification, on a page of St. John across from the wuzz; “Devilled Four and its Possibilities.” Devilling was an eighteenth century English creation and standby, ordinarily a wet combination of fiery spice, always including cayenne and some form, powdered or prepared, of mustard and often other ingredients; soy sauce, mushroom ketchup, and, reaching back to the year 1817, any of the twenty eight bottled culinary elixirs that the inimitable Dr. Kitchiner kept in his beloved “portable magazine of taste,” among other things.

At the time curry powder, and for that matter ‘cayenne’ itself, often contained flour so that the mix was less likely to clump and served as a coating or thickening agent straight from the shelf. (“Authenticity and Appropriation” 41) St. John devilled flour for the larder combines those traditions while stripping them to an essence, of nothing but the flour, cayenne, dry English mustard powder and the universal salt and pepper. Cooks at St. John’s reach for the devilled flour to season kidneys, pig’s ear, sprats, that unpopular tripe and Welsh rabbit.

The possibilities of devilled flour are pretty much endless. Any meat, fresh or cooked, lots of fish (whitebait are exceptional dusted with devilled flour and deepfried) and game may be devilled. Although they mislabel it ‘herbed salt,’ in “A Salty Moment,” the people at St. John also make devilled salt with cayenne and mustard for various uses. “A boiled egg,” St. John’s confides, “is a fine solitary standby. With herbed salt it is elevated to a thing of wonder.” (St. John 139)

All this wonder--wuzz, the devilry, elevational salt, even the reference to outdatedness--appear in but three contiguous pages separated solely by a cartoon (“Trotter of Love”) of an exceptionally literate cookbook.

Despite occasional lapses it is difficult to convey how good the food can be at St John. Nowhere has a new potato tasted more of, well, potato.

Gustatory pedants may argue Le Grand Véfour is an apple to the orange of St. John, and they would have a point. Bakers have used apples and oranges in combination for centuries, however; they may not be so dissimilar after all. (see, e.g., “cult of orange”) The different, very different, pair of restaurants represents a metaphor for the different French and English cooking styles that have endured to more and less degree during the last four centuries.

17. To return to the eighteenth century….

In foundational terms Rules in Covent Garden is a contemporary of Le Grand Véfour. The restaurant opened fourteen years later than its French counterpart, during 1798. “Rules,” in common with St. John, and as its website murmurs with boastful understatement, “serves the traditional food of this country at its best--and at affordable prices.”

Those prices are not, however, particularly cheap at either establishment but do provide good value for the money and look like a bargain compared with Le Grand Véfour. “It specialises,” the Rules site continues, “in classic game cookery, oysters, pies and puddings,” including steak and kidney pudding with or without the oyster. The restaurant owns an estate in the Pennines (“‘England’s last wilderness’”) where it sources the game.

The menu at Rules is short and seasonal, its cooking robust, less complicated of course than Le Grand Véfour, blessed with the same clarity of purpose and flavor as St. John.

The surroundings at Rules compare in elegance to Le Grand Véfour in a completely different way, steeped as the place is in the more robust, less ornate English architectural style of the Georgian and Regency era. Cartoons, drawings and comparatively austere paintings, instead of extravagant murals line the room, according to Poet Laureate John Betjamin “unique and irreplaceable, and part of literary and theatrical London.”

Thackeray and Dickens dined there, as well as John Galsworthy and H. G. Wells. So did Graham Greene, John Le Carre, Rosamond Lehmann, Penelope Lively, and they and others wrote about it in their fiction. The linkage of food and literature in English culture has endured, and in its way Rules itself made possible the experiment of St. John and concomitant emergence of English cuisine. Rules had been the literal and figurative keeper of the flame.

Flame keepers.

18. The eighteenth century framework of English foodways.English cooks had launched the most spirited counterattack of the binary battles back when Rules had been founded in the long eighteenth century. “Most of the things” at one dinner party, James Woodforde records in his famous journal, were “spoiled by being so Frenchified in the dressing.” His own kitchen produced nothing but British dishes, many of them using livestock, fruit and vegetables he grew himself.

It has become a bit of a chestnut to cite Woodforde’s contemporary on the subject but when Mrs. Ayrton recounted the antipathy of Hannah Glasse to French food in 1974 the reference was fresh. By 1747, Glasse’s Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy, the century’s bestseller on any subject in any language other than the bible and various ‘anonymous’ pornographic texts, was railing against the foppish, enervating extravagance of French technique.

In typically playful form, with a single punctuation Mrs. Ayrton parodies the outraged and outrageous prose of Glasse in describing “the strength of her indignation!” (Cookery of England 3) She did not overpromise the case and quotes passages that would become famous among scholars of English foodways:

“But if Gentlemen will have French Cooks, they must pay for French Tricks…. So much for the blind Folly of this Age, that they would rather be impos’d on by a French Booby, than Give Encouragement to a good English Cook!” (capitalization, italics and other usage in Glasse original) (Cookery of England 3; Glasse ii)

Glasse goes further to disavow France by claiming that dishes attributed to the country are in fact misnamed. Anticipating a practice that would become pandemic, she confesses that “I have indeed given some of my Dishes French names to distinguish them, because they are known by those Names…. ” (Glasse ii)

The sentiments Mrs. Glasse expresses about the unfortunate fripperies of French food had to have been widespread in the Britain of her time because the book sold so many copies. Those sentiments only would have increased seven years later with the eruption of the actual warfare between these culinary antagonists that would last with only brief interruption until 1815.

19. A dish by any other name….

The ascendant reputation of French cooking during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries stems in part from a misunderstanding. As Mrs. Glasse warned her readers, and as Mrs. Ayrton explains in The Cookery of England,

“it is widely believed that dishes are French if they are given French names…. Very often these dishes are English in origin and of considerable antiquity. Expecting immediate disbelief, I may cite as examples blanquette de veau and poulet a la crème au riz, both of which were served in England at an earlier date than they ever were in France.” (Cookery of England 6-7)

Rice itself had appeared in England some thirty years before it arrived in France. (Cookery of England 6) The same may be said of so many preparations including fricassees and the ancestor of the vegetated crème brûlée served at Le Grand Véfour which, as burnt cream, first arises in manuscripts and print from the pages of English cooks.

Even though Mrs. Glasse refers to the phenomenon, the penchant to label so much as French did not become widespread until the nineteenth century, when some cookbooks even gave steak and kidney pudding, the English avatar, variations on the name ‘pudding a la viande de boeuf et aux rognons.’ ‘Pudding’ alone appears in English for good reason: Whatever the origin of the term, not even Victorian Francomania could concoct a precise enough translation for it in the context of the dish in question. After all the steamed pudding is alien to the French kitchen along with suet, the essential element of the delicate pastry that encases its filling.

Some preparations wear double disguises. The ‘Espagnole’ in Espagnole sauce refers to the sometime source of the ham it requires, not to the sauce itself; it was “[m]ade in England in the eighteenth century.” Then there is “Alboni Sauce,” a complex piquant reduction for game and “true mutton (“not lamb”):” “In spite of its Italian name, even the French always attribute this sauce to the English kitchen.” (Cookery of England 278, 279)

20. Framing ‘the traditional food of this country.’

Eighteenth century English cooks looked both forward and back with no less enthusiasm than Henderson and his twenty first century acolytes. Gervase Markham provides instructions for fricassee in 1615. Robert May does too, during 1685, and so does Mrs. Glasse some seven decades later. It does not much appear in current English cookbooks but lives on in the kitchens of New England and New Orleans, where the English influence is ordinarily underestimated. (“An Appreciation of Richard Collin”)

Pottage, “a preparation that in shorthand lies at the intersection of soup and stew” consisting of “ingredients chopped or mashed, in a highly spiced broth,” dominated the medieval kitchens of aristocrats and gentry as well as the common sort. (“Chowder” 43; Cookery of England 268) Versions of the dish survive in kitchen books from 1707 and 1780 and they are not just historically interesting oddities. Speaking of the 1780 variant, a pottage of fish and shellfish, Mrs. Ayrton “cannot recommend this recipe too highly.” (Cookery of England 268-69, 269)

21. A sweet surprise.

Innovation accompanied the old ways. Sugar consumption rose with the increasing popularity of tea; new desserts and teacakes proliferated apace. Nonetheless the eighteenth century was not so sugary as the conventional wisdom would indicate.

Historians cite different figures, but according to the authoritative and legendary Sidney Mintz, annual consumption did increase in Britain, from four pounds per person in 1704 to eighteen pounds in 1800, which appears to be a big leap but not in the context of the following century. By 1901 the average intake had rocketed to ninety pounds per head. (Jurafsky & Matsumoto 14, citing Mintz; but compare Parker [a bad book] 296)

The raw figures for the eighteenth century through 1850, when the cost of sugar dropped dramatically, may, however, be misleading. Dorothy Hartley is unequivocal:

“The large amount of honey and wax used in old households is astonishing…. There were regular bee garths in the grounds of all large establishments… As honey was the principal sweetener till about the eighteenth century (and continued in country places and for many cookery jobs till the nineteenth), almost every small household kept their own bees.” (Hartley 657, 654-55)

“In Tudor and Stuart times,” that is, until 1714, C. Anne Wilson maintains that

“ordinary folk still met their craving for sweetened food mainly with honey; dried fruits, then much cheaper than sugar, and other fruits and vegetables that were rich in natural sugars.” (Wilson 300)

More recent scholarship casts extreme doubt on the notion that consumption of sugars dramatically increased during the eighteenth century. With a warning that “[m]any nutritional beliefs are based on dogma rather than scientific evidence,” Karen Allsop and Janette Brand Miller found that

“ordinary people ate much larger quantities of honey than has previously been acknowledged. Intakes at various times during history may well have rivalled our current consumption of refined sugar.” (Allsop & Miller 519)

During the eighteenth century English cooks radically reduced the role of sugar and its alternatives in at least one respect.

“It seems,” Mrs. Ayrton observes,

“that our forbears customarily accepted and enjoyed a combination of savoury and sweet flavours, and considered that meat and even fish could happily be predominantly sweetened rather than seasoned mainly with salt.” (Cookery of England 86)

Pies in particular combined the fish and meat with vinegar and other acids, fresh as well as even sweeter dried fruit, sugar and sweet spice. Markham’s ‘Chicken Pye’ for instance

“includes currants, raisins, prunes, cinnamon, mace and salt, and for the added liquor white wine, rose water, sugar, cinnamon and vinegar with egg yolks and the pie crust candied over with rose water and sugar.”

His ‘Herring Pye’ sounds similar.

“It consists of pickled herrings… a few raisins, a few pears, currants, sugar, cinnamon, dates and butter, baked in a crust, to which is added verjuice, … sugar, cinnamon and butter. The crust, here too, is candied over with sugar and the sides of the pie are to be rimmed with sugar.” (Cookery of England 86)

“By the eighteenth century,” Mrs. Ayrton concludes, “it seems that the division between sweet and savory became accepted.” The trend then had been set but the hybrids lingered for some time. A 1694 Receipt Book includes two unsweetened pies among the hybrid versions while “the redoubtable Mrs. Glasse… gives fifteen or so pies, of which only the egg pie contains currants and rose water.” (Cookery of England 87)

A candidate for most valuable chapter from the invaluable Cookery of England is called “The Tradition of the Savoury Pie.” “The meat pie,” Mrs. Ayrton insists with complete justification, “attained its full perfection only in England and held its pride of place from the Middle Ages until the nineteenth century.” (Cookery of England 85)

Primus inter pares in this pride of place is the steak and kidney pie. The judgment of Mrs. Ayrton requires no elaboration. “The best of all savoury pies: an English dish which is famous all over the world.” (Cookery of England 106)

Counterintuitively the pie is no ancient artefact. It was not until the genius of Eliza Acton added the transformative kidney to the mix in 1845 that the iconic pie first appears in either print or manuscript.

Before then there was chicken pie; chicken and steak pie incorporating bacon, hardcooked egg and mushrooms; pies filled with game including pheasant, pigeon, partridge, rabbit, rook and venison, alone or in various combinations with one another, beef and bacon.

Mutton went into a number of pies, sometimes paired with apples or turnips and, in seventeenth century recipes, sugared mincemeat made with the customary dried fruit, orange peel and high sweet spice. (Cookery of England 97-100, 87)

Those pies were served hot but a classic veal and ham pie “from a seventeenth century cook book” (Cookery of England 108) may be eaten hot or cold, while raised pies always consumed cold, bound as they are with a meat jelly that would melt at higher temperature, also have proliferated on the English table.

The most famous of the cold pies, the Melton Mowbray pork pie, has one of those hybrids of savory and sweet as an antecedent, from the fourteenth century. (Cookery of England 113) “The many recipes,” Mrs. Ayrton notes, “are all very simple.” Her choice for The Cookery of England “depends on the flavouring and high seasoning of the jellied stock, and contains nothing whatever but good pork meat and a little seasoning.” The stock is key, laced as it is with onion and other, green, aromatics; bay, marjoram, which appears all over eighteenth century cookbooks, sage and thyme. (Cookery of England 113)

An even simpler eighteenth century bacon pie “bears the closest resemblance to Quiche Lorraine, except that it is covered.” In another English culinary first, versions make their debut earlier than the French tart. (Cookery of England 117)

None of these pies is a curiosity that Mrs. Ayrton would consign to the page alone, so offers her reader not only instructions but reassurance about the trickiest part: “Do not be afraid of making pastry.” (Cookery of England 86, 90) She wants to see the pies of England baked, even tried her hand at the Markham “Chicken Pye,” which in contrast to the strictly savory pies she found heavy and sickly sweet, so offers a more savory variation on its theme.

23. A note on the sources (of pie).

Mrs. Aryton scouted her pies from an array of sources, an indication of their ubiquity throughout every region of England during that long eighteenth century and for that matter Scotland and Wales. She found “a very old recipe from St. Germains in south Cornwall;” “an early eighteenth century recipe… from Shropshire;” a recipe from a Somersetshire farmhouse that goes back to the eighteenth century and probably earlier; several “traditional West Country recipe[s].” (Cookery of England 100, 105, 96, 97-98)

Mrs. Ayrton also includes pies from Cornwall; London; Mrs. Rundell’s New System of Domestic Cookery (1807) Yorkshire; the cook of King George V; and elsewhere. (Cookery of England 117, 118; 107, 99, 103, 110)

Cooks baked their own Melton Mowbray pies everywhere in the countryside:

“All over the Shires every manor house, farm and inn had its special recipe for Melton Mowbray pork pies, which were originally intended for high tea served to returning members of the hunt.” (Cookery of England 113)

Pie’s cousin the savory pudding is even more unique to the country and it is appropriate of Mrs. Ayrton to include an addendum of recipes in her chapter on the tradition of pie, although she scatters more of them elsewhere. A particularly good and obscure one, called simply “Savoury Pudding,” appears in the chapter of stuffings and forcemeat, themselves uniquely English contributions to the table, because it is a traditional accompaniment to pork or goose.

From “the big farms of Cumberland and Northumberland,” the pudding derived of course from the essential suet pastry--no other crust turns out so fluffy and light--is made with a mixture of breadcrumbs, flour and oatmeal seasoned with parsley, sage and thyme bound together with egg and milk. (Cookery of England 299) A lot lighter and more complex than it sounds, indeed a beguiling composition good with more meats than the traditional two as well as with all kinds of roast birds whether fowl or game.

Forcemeat and stuffings “have always been very important in the highest levels of traditional English cookery.” The usage of the syllable ‘force,’ Mrs. Ayrton takes time to explain, derives not from exertion but from a nearly archaic term for ‘mince;’ all the elements are cut fine, both to marry and distribute their strong flavors.

The genius of forcemeat, so long as it has sufficient fat to leach, lies in its bipartite purpose. A nice turn of phrase from Mrs. Ayrton describes the effect: “The meat which is stuffed flavours the stuffing, the herbs in the stuffing flavour the meat.”

Forcemeats, also usually suet based, did not only serve to stuff birds. Rolled into balls or formed into small cakes, it may go into the fillings of pies or puddings and may be fried for service alongside roast birds, game and meats.

The forcemeat palette usually consists of a typical English combination of rich and tart, its flavor profile colored with acid (citrus zest variously of lemon, sweet or sour orange), depth (mushrooms), brightness (herbs, most frequently marjoram, parsley, sage and thyme), fat (the suet and sometimes butter or cream), sometimes heat (the bite of empire in the guise of cayenne), smoke (bacon), and the elusive umami (usually through the agency of anchovy or oyster).

In addition to its salutary contribution to the complexity of a dish, forcemeat has a utilitarian side understood quite well by the less fortunate but nonetheless resourceful cook.

“The poor housewife would rely on it to eke out the meat and help fill the hungry children, who got plenty of stuffing but only a small slice of meat.” (Cookery of England 296)

That was not necessarily so bad; good stuffing can be the best part of supper.

25. along with lots of other things: A sprint through the English kitchen.

Savory pies with or without forcemeat balls nestled in their fillings may have enjoyed pride of place on the English table but hardly stood alone. The Cookery of England displays so extensive a range of dishes, from light salads to all the robust pies and famous sweet puddings, that it is possible to mention only a small sample of them.

Mrs. Ayrton provides a welcome corrective to the myth that English cooks always have boiled anything green to pulp. “Salads, which,” she writes, “are sometimes thought only to have been seriously considered in recent times,… were in fact longed for by our ancestors through the hard winters of salt meat, bread and sparse roots.”

In fact as John Evelyn demonstrates in his 1699 treatise Acetaria, where he “discusses with immense bravura and polymathy the merits of salad” (prospectbooks), salads in England re more varied and sophisticated during the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries than they have become around the western world today. Then,

“first shoots of a wide variety of herbs, wild and cultivated, were eagerly awaited, and a far greater variety of leaves, roots, buds, flowers and shoots were used than we ever consider today.” (Cookery of England 374)

Not only greens, and not only raw ingredients, found their way into late seventeenth, eighteenth and early nineteenth century English salads. Then and now, English salads combine raw and cold cooked elements to an extent not found in the United States.

The most renowned of historical English salads, salamagundi, which Mrs. Glasse called ‘Salamongundy,’ resembles the chef’s salad much in vogue during the 1970s, not least at the Palm Court of the Plaza Hotel in New York. Mrs. Glasse artfully arranges cold roast chicken, strips of the white meat and dice of the dark, along with anchovy, mashed cooked egg yolk, grapes, diced lemon and parsley in rings and tiers on lettuce shred “as fine as a good, big thread,” exemplary eighteenth century writing there, tops the edifice with pearl onions and dresses the salad with vinaigrette. (Cookery of England 385)

Other salads may be less familiar to modern eyes. One of them combines mushrooms with lettuce, sliced orange and “finely chopped walnuts,” another, from the eighteenth century, is composed of cooked artichoke bottoms and asparagus, once again lettuce, garlic (rubbed about the salad bowl in the traditional manner) and “cubes of bread fried crisp.” (Cookery of England 384, 380)

It was not until the nineteenth century that “vegetables became a duty;” before then, English diners anticipated the seasonal advent of peas, especially asparagus and broad beans as they still do, and made extensive use of things no longer associated with the country’s cooking; artichokes, fennel, others. (Cookery of England 346) Woodforde writes with evident relish of his vegetables; Mrs. Glasse counsels her readers not to overcook any of them, advice the Victorians spurned.

The English acquired a carnivorous reputation long ago: “Meat and particularly roast meat with a fine sauce or gravy was what everyone, male or female, noble or peasant, wanted for the dinner and the supper table” until, that is recently.

English tastes have become cosmopolitan and omnivorous. In a nod to tradition, however, and to her times, Mrs. Ayrton includes some fifty four pages of recipes for meat and another fifty six covering poultry and game along with her extensive collection of savory puddings and pies.

Spiced stock, “traditional in high-level cookery in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries,” gives yet another lie to the claim that English cooking omitted spice. Once a large chunk of beef had been boiled, its stock would be drawn off and seasoned with white pepper, saffron, turmeric, orange zest and juice; “the liquid should be a clear bright golden colour.” (Cookery of England 53)

Incidentally the use of saffron in England dates to Roman times. The name of the London borough of Croydon descends from the Latin for ‘saffron valley.’

During the nineteenth century the Garrick Club specialized in a casserole of game and beans. A noble diner said “‘It’s the beans make the bird., “‘You mean,’ replied another, ‘It’s the bird makes the beans.’”

Let’s all stare at this poor woman.

No saffron in that dish but either noble interpretation would do; the recipe Mrs. Ayrton provides is extremely good, redolent of marjoram, parsley and thyme, spiked with bacon and mushrooms bathed in red wine. (Cookery of England 190)

The kind of droll anecdotal aside about the diners at the club peppers The Cookery of England to delightful effect. To introduce an early nineteenth century North Country recipe for beef simmered in a piquant broth of ale, vinegar, a shower of herbs, sweet spice (cloves, once again mace and turmeric), vinegar and the essential, undetectable trace of treacle that pulls it all together, Mrs. Ayrton recounts its myth of origin:

“The tradition in the household was that the dish had been prepared in the past by their parsimonious ancestors for the hay-making supper for tenants, because part of an old ox which had been kept to work all winter could be used, since the beer helped to tenderize the meat. The tenants liked the taste of the beer and considered the dish a grand one.” (Cookery of England 53)

The tenants were right.

There is of course a selection of curries and a recipe for mulligatawny soup, Raj creations inspired by the foodways of the Subcontinent but of a peculiar British character.

Some savories involve meat, along with her potted products, brawns, galantines and terrines. Despite all that, The Cookery of England does not short the fishmonger. Among the fifty eight or so pages of seafood recipes are some sophisticated preparations, many of them, like an airily light ‘watersouchy,’ begin with a courtbouillion, many of them combining finfish and oysters in the eighteenth century manner.

And so to sweets, our final course. There are too many to provide much detail--creams, fools, possets, syllabubs, trifles and more in addition to the countless steamed puddings. One sample will need to suffice.

Nobody now knows flummery, but many good variations exist and someone cooked this particularly appealing one back in 1760. It is short enough to cite Mrs. Ayrton’s pellucid prose in full:

“Soak 3 handfuls of fine oatmeal in cold water for 24 hours. After this time add an equal quantity of water and leave another 24 hours. Strain through a fine sieve, add a heaped tablespoon of caster [granulated] sugar and the strained juice if an orange.

Boil until very thick.

Pour into shallow dishes and serve with honey and cream.” (Cookery of England 469)

Note the economy of language, assured tone and absence of false precision while pouring the flummery into six to eight portions depending on the appetite of the diners.

26. Hiding in plain sight.

All this traditional variety appeared in print eight years before the Cowans found English Provincial Cooking a revelation, and the foodways of England remain relatively obscure in the United States. Good things, as the founders of St. John understand, should be a constant, and books at least endure. The rewards of the English canon are there for American readers’ taking and the work of Elisabeth Ayrton is a good place to look.

Sources:

Eliza Acton, Modern Cookery for Private Families (London 1845)

Karen Allsop & Janette Brand Miller, “Honey revisited: a reappraisal of honey in pre-industrial diets,” British Journal of Nutrition 75 (1996) 513-20

Anon., “Britain is built on sugar: our national sweet tooth defines us,” The Guardian (13 October 2007)

Anon., http://www.grand-vefour.com/en/menu.html (accessed 14 June 2020)

Anon., www.prospectbooks.co.uk/products-page/current-titles-acetaria/ (accessed 18 June 2020)

Elisabeth Ayrton, The Cookery of England (London 1974)

The Doric Temple (Utrecht 1961)

English Provincial Cooking (London 1980)

Good Simple Cookery (orig. publ. London 1958; revised ed. 1984)

Michael Bakewell, Fitzrovia: London’s Bohemia (London 1999)

Jessica Castrodale, “French Food Actually Sucks Now, Says Head of French Tourism Council,” Vice, https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/pa.5qnm/french-food-actually-sucks-now-says-head-of-french-tourism-council (6 December 2018) (accessed 10 June 2020)

Lisa Chaney & Harlan Walker (ed.s), “Saturday Night Dinner,” Proceedings, Oxford Symposium on Food and Cookery 1990: Feasting and Fasting (Totnes, Devon 1990) n.p.

Derek Collett, His Own Executioner: The Life of Nigel Balchin (Bristol 2015)

Linda Colley, Britons: Forging the Nation, 1707-1837 (London 1994)

Rachel Cooke, “St. John’s five rules for success: ‘No music, no art, no garnishes, no flowers, no service charge,’” The Guardian (17 August 2014)

Claudia and Walter Cowan, “Cookbooks,” The Virginia Quarterly Review vol. 58 no. 4 (Autumn 1982) 138-41

Lara Feigel, The Love-charm of Bombs: Restless Lives in the Second World War (New York 2013)

Sarah Gillies, “Reflections in 18th Century Taste,” in Tom Jaine (ed.), Proceedings, Oxford Symposium on Food and Cookery 1987: Taste (Totnes, Devon 1988) 74-81

Adam Gopnik, “Is There a Crisis in French Cooking?” The New Yorker (28 April 1997)

Dorothy Hartley, Food in England (London 1954)

Fergus Henderson, Nose to Tail Eating: A Kind of British Cooking (London 1999)

Fergus Henderson and Trevor Gulliver, The Book of St. John (London 2019)

Justine Hopkins, “Ayrton [nee Walshe: other married name Balchin], Elisabeth Evelyn,” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, https://ezproxy-prd.bodleian.ox.ac.uk:3030/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001 (23 September 2004) (accessed 18 March 2020)

Michael Ayrton: A Biography (London 1994)

Dan Jurafsky & Yoshito Matsumoto, “Sweetness and Power,” Think 53: Food Talks, web.stanford.edu/class/ (11 May 3017) (accessed 17 June 2020)

William Kitchiner, The Cook’s Oracle (London 1817)

Robert May, The Accomplisht Cook (orig. publ. London 1685; 2000 facsimile Totnes, Devon)

Sidney Mintz, Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History (New York 1985)

Matthew Parker, The Sugar Barons: Family, Corruption, Empire and War (London 2011)

Blake Perkins, “An Appreciation of Richard Collin… along with a related discussion of fricassee,” www.britishfoodinamerica.com No. 4 (February 2010)

“An Enquiry into the Derivation of Chowder,” Petits Propos Culinaires 109 (September 2017) 32-67

“Authenticity and Appropriation: The Southern United States and Scotland,” Petits Propos Culinaires 116 (March 2020) 26-46

“The cult of orange, Fly Girls & a Smart Aleck,” www.britishfoodinamerica.com (Summer 2020)

Maria Rundell, A New System of Domestic Cookery (London 1807)

Wendell Steavenson, “The rise and fall of French cuisine,” The Guardian (16 July 2019)

Michael Steinberger, “Can Anyone Save French Food?” The New York Times Magazine (30 March 2014)

Anne Wilson, Food and Drink in Britain From the Stone Age to the 19th Century (Chicago 1991)