A note on London clubland past & present.

1. Origin and evolution.

The genesis of the London club is the coffee house. The redoubtable Robin McDouall dates the first one in England to Oxford during 1650, the first in London two years later. Its proprietor brought with him from Smyrna a servant called Pasqua Rosa, skilled in the exotic and medicinal art of brewing coffee.

He extolled its qualities with the ardor and possibly mendacity of an evangelist:

“As well as being delicious, the coffee would prevent and cure, according to Rosa, dropsy, gout and scurvy; it was a digest, good for sore eyes, would quicken the spirits and make the heart lightsome. No wonder Mary Baker Eddy, a couple of hundred years later, banned coffee for Christian Scientists.” (Clubland 7; emphasis in original)

And so we are off, on the jaunt McDouall calls Clubland Cooking. Coffee house as a descriptor was, he explains, from the outset an understatement. A house did pour coffee but always offered other delights that would equally appall Baker Eddy: “It was not dry.” An early one, Garraway’s, “was famous for its champagne and anchovy toast (what a good combination!).”

The houses stocked newspapers; “mutton pies, cheese, cakes and custards were on sale.” We could do with a few of these places in New York today: By 1700 lucky London alone supported between two and three thousand of them. Lloyds is the most famous surviving manifestation of a coffee house because before there was Lloyds the insurance market there was Lloyds the house.

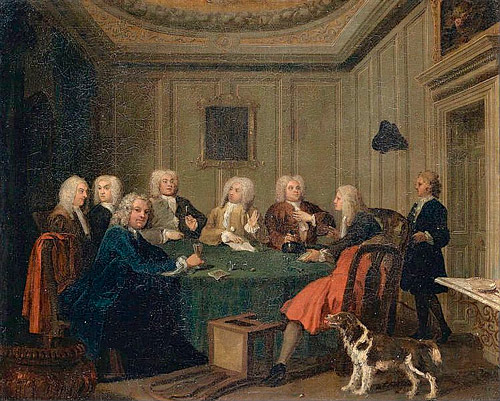

Some of the houses attracted likeminded men (for then they all were men) or at least men engaged in similar affairs and Lloyds was one of them. One house catering to the eighteenth century Tory was the Cocoa Tree, and McDouall quotes Gibbon’s famous description of a 1762 evening there in some detail. Gibbon had recorded one of the earliest references to a sandwich but McDouall’s interest lies a little afield, in the evolution of coffee house to club. The Cocoa Tree was among the earliest converts. Gibbon wrote that the place,

“of which I have the honour of being a member, every evening affords a sight truly English. Twenty or thirty, perhaps, of the first men in the kingdom in point of fashion and fortune supping at little tables covered with a napkin, in the middle of a coffee room, upon a bit of cold meat, or a sandwich, and drinking a glass of punch.”

“Note three things,” an acute McDouall instructs his reader:

“the Cocoa-Tree, one of the oldest and most distinguished coffee-houses… had become a club; the dining-room was called the coffee-room; the great drink was punch.”

The English have their own linguistic ways and the coffee room, as McDouall remarks, has become the only place in clubland unlikely to offer anyone coffee. As the house became a club, its coffee room had become the dining room.

McDouall charts the process of transition. In contrast to its contemporary taverns, a seventeenth century coffee house charged a fee for entry. It was modest at first but as the years progressed and the offerings proliferated the tariff increased apace. As the likeminded became regular customers they might rent themselves a room. Eventually “the whole building was set aside for the subscribers who paid to keep the casual passers-by out.”

2. Gloom and illumination.

Clubland hit its apogee during the long eighteenth century. Members held the political heights at Westminster, brokered affairs of state and set the cultural agenda of the establishment from their palazzos lining Pall Mall and St. James. Over the course of the 1800s, however, with the signal exception of the National Liberal, the clubs lost much of their creative dynamism. “A Victorian gloom,” McDouall laments, “settled on them in the last century. Guests, if not barred, were discouraged. Members rarely spoke--certainly never to strangers.”

That began to change, along with much else at the pinnacle of British society, with the ascension of Edward VII. In Ireland however retrograde elements of the Ascendancy refused to clear the grim old atmosphere into the twentieth century. An apocryphal McDouall recounts that he “once dropped a pin in the Kildare Street Club, Dublin, and heard it meet the carpet avec un bruit sec.” (“Club Subscription”)

That happily no longer is the case. A dinner with the late lamented historian L. P. Curtis, Jr., civil servants, lawyers and others from both sides of what at the table no longer is a sectarian divide filled the dining room with robust assertions and vehement responses worthy of the most raucous Big House debauch.

Back in London, the Second World War in which McDouall served as a Wing Commander in the Royal Air Force had wrought wrenching change to clubland. In 1958 he describes a sort of ecumenical approach to membership that previously was unthinkable. “Clubs,” he found, “have been wise enough to accept the social revolution of our time, to dilute the social whisky,” noting that he himself had become a member of “two clubs [he] never would have aspired to join before the war.” (“Club Subscription”)

3. An outlier from the outset.

The National Liberal Club did not experience the social revolution that shook midcentury Britain because the club anticipated its liberalizing ethos by over fifty years. It has remained an outlier: While he does refer to quite a few clubs in Clubland, McDouall does not even note the existence of the National Liberal. Even so, the club is a club and therefore hardly a beacon of informal anarchy. “Like most clubs,” its website explains, “the National Liberal Club has a dress code; but as a liberal club, we strive to have rules that are flexible and reasonable.”

Gladstone founded the place in 1882, unlike other prominent clubs in Whitehall instead of St. James (excepting the Garrick in Covent Garden, which makes sense). From its inception the National Liberal

“was conceived as a club that should be able to outshine any of the more established aristocratic clubs of London; but for membership to remain much more accessible than other clubs. It was one of London’s first major gentlemen’s clubs to admit women as full members; and from its launch… it was unusual in embracing a diverse range of members of many different ethnic, social and religious backgrounds.”

Not that the members of the National Liberal historically have shone with a dimmer light than its rivals or that its house lags them in elegance. Asquith; Churchill; Lloyd George; Jinnah, the first prime minister of Pakistan; and Ramsay MacDonald are among the statesmen: Rupert Brooke, G.K. Chesterton, George Bernard Shaw, Bram Stoker, Dylan Thomas, H.G. Wells and Leonard Woolf among the cultural icons.

Alfred Waterhouse, one of the more progressive Victorian architects, designed the club’s elegant Italianate pile along with the Natural History Museum in Brompton Road, the soaring Manchester town hall and other monumental commissions.

Notwithstanding its founder and name, the National Liberal is unaffiliated with any political party, although it does distinguish its ‘Political Members’ from its ‘Members,’ who “sign a declaration that they will not use the club’s facilities for any political activities adverse to Liberalism,” which, however, is not defined despite its capital stature.

A hint may perhaps be provided by the Dress Code (capitals in original), written with a concise panache worthy of the Internal Revenue Service regulations. With few exceptions, and despite its specificity and length, the Dress Code nearly amounts upon diligent close explication to no dress code, a least in the cases of women and transgender or nonbinary people (both “(members and guests)”):

“i) Members and guests are required to wear smart business or smart casual clothing in the Clubhouse at all times. As in the past, a polo-neck or roll-neck sweater [note the American usage instead of ‘jumper’] is also acceptable in place of a collared shirt for men, as is traditional, religious or national dress or uniform.

ii) Male members and guests will be required to wear a jacket and tie, or an authorized alternative (see above), every evening in the Dining Room after 6.30 pm, throughout the year.

iii) Male members and guests will be required to wear a jacket and collared shirt (tie optional), or an authorized alternative, at all other times in the Clubhouse from September to May inclusive.

iv) During the summer months of June, July and August, male members and guests will be required to wear a collared long-sleeved or short sleeved shirt, or an authorized alternative, on the Terrace or in the Clubhouse (jacket, tie optional except in the Dining Room after 6.30pm--see above).

v) A transgender/non-binary person (member or guest) is free to select the dress code that matches and is appropriate to the gender in which they present.

vi) Members and guests are required to comply with the specified dress requirement when attending Club events.

vii) Members and guests are not permitted to wear any of the following: tracksuits, sportswear including polo shirts, trainers, shorts, ripped or torn clothing, clothing bearing any slogan or prominent words.

viii) The requirements of the dress code shall not apply when there is a bona fide medical reason for non-compliance.” (“National Liberal Club”)

A team of specialist counsel is standing by in the Clubhouse before 6.30 pm to assist.

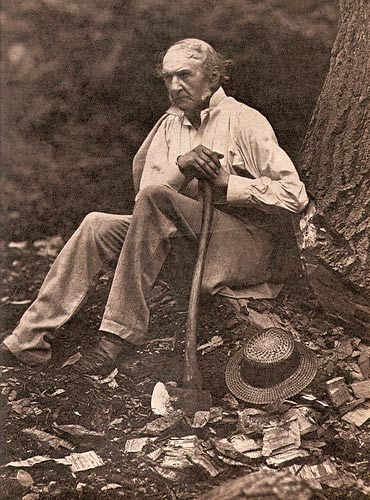

To top things off the National Liberal’s reading room includes a display of Gladstone’s iconic axe, which he used to dissipate his sex drive by doggedly splitting firewood following the interviews he liked to conduct with prostitutes. His tool is not apocryphal after all.

A man and his axe.

4. A foundation of foodways.

Food always had been central to the foundation of a club. “A pound a year as a contribution for a good cook might,” McDouall explains, “be the beginning.” (Clubland 9) Interior space in any building is finite so coffee houses set limits on the number of people who could appear at any given time. That limitation in turn led to the practice of electing members which, at the outset, did not embrace the blackball that allowed any single member to bar an applicant. (Clubland 9-10)

Some, more than a few, places still employ the blackball. One of them is one of the most storied, the Travellers Club, where McDouall himself served as secretary, or major domo, for several decades following the war. (Clubland 10; Yorke) At the end of 1958, McDouall wrote uncritically of the clubs that they remained “primarily eating-places, where committees do their best to keep membership to people who know each other or, if they don’t, wouldn’t mind doing.”

5. A retrograde revolution.

At midcentury clubland had diverged from its original domestic atmosphere by remaining unchanged. As the fortunes of the great houses declined, their numbers dwindled and the servants disappeared, clubs became, for McDouall anyway, the tranquil refuge from an unwelcome modernity. “The idea that a club should be as much like a member’s home as possible” where, he explains,

“the food and wine for dinner ordered by the member in the morning, the dishes coming in from the left from the hand of a knee-breeched footman--has gone. Gone with the footman.”

Instead of replicating it,

“the club should be as unlike home as possible…. Retaining as much as they can of the atmosphere of the past, if only the décor and furniture, clubs are now the bolt-holes from the ardours of home life, the squalor of works canteens and city restaurants.” (“Club Subscription”)

City of course refers to the City of London--London, after all, was McDouall’s milieu--and so to work, a disagreeable inconvenience of relatively recent origin for much of the clubland population.

Among other changes buffeting postwar Englishmen of a certain cast, if not an altogether disagreeable one, was the intrusion into the British household of foods formerly considered foreign, with the exception of the longstanding fetish for a ‘French’ cuisine often misunderstood and therefore bowdlerized by their cooks. In common with the footman most of the cooks had gone by the fifties as well, when much of the cooking devolved onto the newly worldly wives of the members.

The revolution wrought by Elizabeth David had, for good and for ill, transformed the prosperous British kitchen. Her credo; out with traditional English technique and in with the exotica of provincial France and the Mediterranean rim. Her dogma dominated not only the urban British household but its restaurants as well.

Elizabeth David in her kitchen.

6. England our England… but sometimes our France.

Clubland resisted, and to a considerable extent continues to resist that revolution. “In spite of our French chefs,” McDouall could write in 1974, “club food has remained good, plain English food…. For the daily menu the demand is the plainest--some might say the dullest.” (Clubland 54)

Elsewhere he drops any reference to dullness and extends the culinary reach of the club kitchen:

“From the earliest days of clubs, food seems to have developed on two lines: first, there is the very simple food of the chop-house: the chop, the steak, the sandwich, the savoury. Then, for private parties, there have always been the sumptuous meals, cooked by a French chef in the French style. The resulting evolution is that today club members like home cooking--call it, perhaps, country house cooking, with a strong emphasis on what I can best describe as nursery food.”

Savory pies, unknown to the French cook, always were “an essential feature of club life. Summer or winter there always are three or four to choose from on the cold table;” for hot dishes there was “a kind of tradition in clubs that everything, if possible, should be grilled.” (Clubland 77, 73)

Mania for the grill, or broiler, did not originate from a strictly culinary rationale but rather a dubious ideological one. Grilling is thought, by club members of a certain age, “to be manly: ... ‘made up food’ rather feminine or even sissy.” The effect on some dishes might be somewhat baleful. “Grilled turbot,” for example, “isn’t nearly as good as poached turbot but, in response to demand, clubs do it.” (Clubland 73)

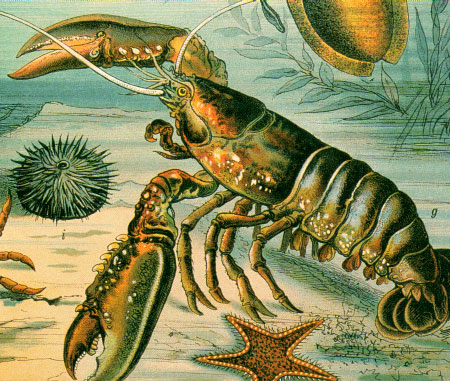

The French line does not embrace the rural and Mediterranean ‘peasant’ styles promoted by David but rather the rich, lavishly sauced northern cuisine of the metropolis reinterpreted for British taste. “When occasion demands,” McDouall explains with an inferential critique of the richness itself,

“the chef must abandon the curried chicken, the apple tart and the ground rice pudding and produce lobster Thermidor, tournedos Rossini and Nesselrode pudding--not all, I hope, at the same meal.” (Clubland Cooking 18)

Not we hope, at any meal; the home-country house-nursery cooking is not nearly so heavy and paradoxically packs more punch.

7. ‘Contemporary’ cuisine.

McDouall’s description of daily fare in 1974, along with the recipes he selected for Clubland Cooking, describes equally the food offered by the National Liberal Club today. The club did not originate as a coffee house and unlike other clubs does not call its dining room a coffee room. A menu from early December includes potted crab, smoked salmon and Jersey oysters to begin; goose with parsnips, pheasant in Port sauce, Dover sole, roast turkey with traditional trimmings, venison braised in red wine with chestnuts and mushrooms along with evergreens in the guise of lamb cutlets, a mixed grill and three kinds of steak for mains; on occasion savory pies, and steak and kidney pudding appear.

Unlike those socially promiscuous Liberals, the secretive Travellers only allows members access to its website except for the uninformative homepage, so the kind of food the club now serves is known only to initiates and their intimates. In similarly mysterious mode McDouall attributed only about an incongruous handful of recipes to his own Travellers kitchen in Clubland Cooking; chicken salad; potted ham; pates of hare and of kipper; salsify; Travellers pie made with a mix of ham, pork and veal marinated in Sherry.

Then again he does not divulge the origin of most recipes in the book. Should we assume that they arose from his kitchen? Probably not. McDouall admits that he chose to include in Clubland Cooking

“ ….recipes which are used in clubs--some contributed by the chefs of clubs, most consisting of recipes which I know that clubs do or, if they don’t, which I think they should do.”

That last phrase gives him a remit beyond clubland, so a recipe from ‘a Cambridge college’ and others via Florence White appear, along with references to Lady Clarke of Tillypronie, the inevitable Elizabeth David (a recipe for Beef Wellington that she characteristically insists on calling ‘Filet de Boeuf en Croute’), Meg Dods and other exemplary but unclubby characters.

Whatever the source of his recipes, McDouall is neither fool nor slob. The lobster Thermidor, tournedos Rossini and Nesselrode pudding do appear, and more generally the recipes in Clubland Cooking do fit the general description of club food he sets forth in its preface. An assessment of the cookbook appears in the practical.

8. An Appreciation of the NLC.

If the National Liberal is representative, and that may be an unwarranted assumption given its progressive history, clubland remains not only kind to its members but also has become welcoming to their guests. McDouall certainly thought so in 1958. Circumstances even more straitened now than then may explain the attitude--clubs suffer from a crumbling financial foundation and need whatever revenue they can scrounge--but regardless of cause the effect at the National Liberal anyway is salutary. Our generous hosts there have been Beata and Robert Brooks.

Dining Room, National Liberal Club.

Sources:

Anon., “National Liberal Club,” www.nlc.org.uk (accessed 2 December 2019)

Robin McDouall, Clubland Cooking (London 1974)

“The Club Subscription,” The Spectator (26 December 1958)

James Yorke, “Home at last--a celebration of 200 years of the Travellers Club,” The Spectator (September 2018)