Occasional Miscellany, or, disparate approaches to adversity & the egg.

Time, in terms of the human as well as legal contract, always has been of the essence. Cookbooks that promise shortcuts in the kitchen therefore have found a market since before the twentieth century. Some have been better than others, many of them offering little more than the false promise of extremes, based as they are only on either overprocessed or extravagant ingredients. A particularly good example of the genre relies exclusively on both categories.

1. A southern eccentric and her eccentric cuisine.

Good fast recipes may be found in books that do not trumpet timesaving, some of them from sociable authors happy to entertain the unexpected guest. One of them, the eccentric Favorite Recipes of a Famous Hostess written by the eccentric Daisy Breaux in the epochal year 1945, is the subject of an essay in the lyrical.

Her fast recipes are hybrids of high and low, combining for example crab or shrimp with canned soup; angels on horseback inexplicably misnamed pigs in blankets along with a cheap and cheerful variation that wraps olives instead of oysters with bacon for bronzing under the broiler. Elsewhere Breaux substitutes liverwurst for foie gras and olives for truffles in a terrine that is different but not necessarily inferior to its pricy prototype. It is her ‘Calhoun Concoction’ and also includes buttermilk or, in a pinch, milk soured with lemon juice, lemon juice with the buttermilk and some canned mushrooms along with a pair of pantry staples, Tabasco and Worcestershire.

Not so fast goes one of several techniques Breaux describes to prepare a quick classic, the omelet. Her own eccentric and complicated method that she inexplicably labels simply an ‘omelette’ (her preferred but not exclusive spelling; in terms of literary if not always culinary style more is more for Breaux) and later, in passing, a “beaten omelette.”

Breaux begins her beaten omelet by separating yolk and white. She adds two icy teaspoons of cream or single ‘dessertspoon,’ as Breaux describes them instead in the better late lamented usage, per yolk (she considers the extreme temperature essential and suggests ice itself as an alternative) along with a pinch of cornstarch before beating the mix with twelve swipes of a fork, never more nor less and never performed with a whisk. After whipping the whites with one “until stiff enough to stand at a peak” she adds some salt and “a pinch of baking powder, which makes the omelette fluffy and helps to make it rise.”

The cooking technique itself follows French convention. Breaux turns the combined mixtures into a pan preheated over medium heat and slashes at the eggs as they barely start to set: “This must be done in the beginning so that the surface will not be uneven.” Once the creation has cooked, Breaux executes the tilt, flip and roll technique that never fails to bedevil novitiates. “Of all egg dishes,” she has the candor to warn, “the omelette is the most difficult to properly prepare.”

Breaux then offers her reader both a “plain French omelette” and a “plain omelette;” each of them is simpler to prepare but not to execute and can become the platform for a handful of filled and garnished traditional variations. All of them call for simply beating the eggs rather than separating, enhancing, whipping, recombining… but still with the twelve sacrosanct strokes of a fork.

Her favorite is a staple of British cookbooks, “The Rum Omelet: The king of omelets. Either the plain or beaten omelet [sic] may be used for this concoction.” (Breaux 55) Breaux does not identify the king as a dessert but probably figured that its goes, as they say, without saying because the eggs are sweetened as well as spiked.

2. A merry fraudster from New York; “Mad Men” have nothing on him.

If the tone Breaux takes is chatty and confidential, The Madison Avenue Cook Book by Alan Koehler is outright outré. Its premise, that all advertising is false, governs the author’s philosophy of cooking and food. The host (but not always; remarkably for a book from 1962, Madison Avenue includes a couple of references to the aspiring hostess too) must entertain for the purpose of getting ahead and cannot be seen to offer anything but the best in terms both of technique and ingredients. In terms of technique that is not an honest option for the uninitiated cook, and that is where the application of deceit saves him:

“This book, for people who can’t cook and don’t want other people to know it, tells you how to appear to know a good deal about cooking when actually you know little or nothing. And how to make two or three basic ideas seem like an embarrassment of riches.” (emphasis in original)

The cooking itself is not key:

“Remember you are not perpetrating dinner but a deception. Your ravishing food notwithstanding, your primary concern is to mislead, however fortuitously you may nourish, your guests.”

Instead, the key, as the student of Advertising 101 will know, is shameless promotion because the ego-driven business assumes practitioners who “say nothing know nothing.”

“If,” Koehler continues,

“you seriously wish to conceal your helplessness in the kitchen you can’t just keep quiet about it. You must, instead, tell everybody you can cook the pans off practically anybody… and must, alas, produce ‘proof’ to back up your boasts from time to time.”

That may appear to the uninitiated an insoluble conundrum but, it transpires, paradox rides to the rescue:

“Fortunately no artifice is so effective in concealing the fact that a person cannot cook as… cooking! Yes, now you can keep the secret that you can’t cook safe--through cooking! Little need even your most worldly or suspicious guest suspect that dinner isn’t really dinner at all, but merely a ruse to conceal your inability to cook! (emphasis also in original)

2. The (now ethereal) omelet redux.

By now it should be apparent that the noncook should not actually offer anybody his specialty, the “ethereal omelet that the sleepiest stirring of southern breeze would surely waft away.” While requisite to reinforcing your reputation for wizardry, an omelet is, as the detailed instruction of Breaux indicates, impossible for the kitchen incompetent to execute. Instead, offer your guests “Eggs a la Ruse,” but “only on impromptu occasions,” which have been carefully choreographed in advance,

“like after the theater, never by invitation and never for breakfast, which it is beneath the station of a Madison Avenue cook even to acknowledge the existence of, let alone prepare.”

Words to live by on the breakfast front.

As for the phantom omelet, Koehler does provide “a recipe to memorize, and never ever for a Madison Avenue cook… to attempt to actually prepare” along with an alternative technique for those who wish “to not-make an omelet a still more difficult way.”

3. Tools of deception.

Time along with fraud is of the essence; although a small minority of the few recipes in Madison Avenue take some time, the ambitious advertising executive cannot in reality tarry in his kitchen too often which in any event is likely to be undersized and poorly equipped. Madison Avenue anticipates how to blunt the awkward reality of those constraints. Never allow anyone near the kitchen, in no small measure because its required equipment includes only an otherwise inadequate battery that would betray the incompetence of its keeper:

“1 pan

1 pot

1 frying pan

1 lid

1 knife

1 fork

1 spoon

1 can opener

1 coffee pot

1 blender

1 stove

There’s nothing more to buy!”

The can opener is particularly vital:

“Ready-prepared foods are used wherever possible. Their use, should anyone have the temerity to raise the question, must be deprecatingly denied. Of course their wrappers, jars or cans are thrown down the incinerator, and they are always doctored somehow so even their own Aunt Jemima wouldn’t know them.”

Misdirection, in particular the art of misleading without lying, is another friend of the unaccomplished cook. Koehler for example advises his reader to

“let a certain honesty, that will later be interpreted as modesty, creep obliquely into your telephoned invitation [this, remember, is 1962] to guests: ‘Come over a week from Thursday for a drink about seven, and maybe I’ll open a can of something so we don’t have to go out.’ At dinner no one will dream that chances are this is exactly what you have done!”

Essential tool number one.

Nor can the fraudulent consider disclosing either a unique “Mystery Touch ingredient” (always, however, rosemary or basil, and always dried) or the ‘secret’ component, in fact a commodity sometimes incongruously added to the dish in question, embedded within each recipe.

The lavish use of herbs (“When in doubt (and when not), too much is always better.) along with spice, usually hickory smoked salt and cracked pepper, nothing more, although curry powder recurs in unexpected locations, and especially garlic “provide the foundation of Madison Avenue cooking:

“Use as much as you can without losing the nerve to deny under cross-examination that you’ve used any at all. Even people who say they loathe or are allergic to garlic don’t and aren’t, provided you can convince them it isn’t there. Garlic, anonymous, is universally loved.”

Camembert, “the ingredient the identity of which to carry to your grave,” is the secret to those Eggs a la Ruse, along with curry powder, white wine and the mountain of butter found nowhere but in the kitchens of the most elegantly extravagant restaurants or the subsidized surplus warehouses mandated by the Common Agricultural Policy of the European Union. It is, surprise, a good dish indeed, along with just about the entire succinct selection of recipes in The Madison Avenue Cook Book which, however, in contrast to reputable cookbooks must remain under wraps:

“A detail vital to the success of your cuisine is to keep The Madison Avenue Cook Book concealed whenever your guests are at large. (You may feel more confident if you have a number of authoritative prop cookbooks on prominent permanent display, like the stage-luggage law books in a lawyer’s office, but these remain uncracked) No one may know your repertoire includes only those recipes here.”

4. ‘Perfection’ has its price.

None of this comes without cost:

“Money, regretfully, cannot be an object. Only the choicest fresh meats and produce may be admitted to your kitchen. Your steaks and chops must be so thick they can only be conspicuously consumed. The voluptuousness of your chickens derives from Rubens, not Reuben’s.”

In terms of produce Koehler offers counterintuitive but indispensable advice that would benefit even the most accomplished cook because

“most shoppers choose underripe specimens… instead of desirably deadripe ones. Deadripe produce will not keep, true, but who wants to keep it? Apparently everybody; greengrocers live literally up to their name and sell everything, naturally green or not, green. Some greengrocers even quarantine ‘overripe’ produce and cut the price; this is what to buy, and at the last possible moment before the meal begins is the time to buy it.”

Indispensable props other than Madison Avenue also may be obtained on the cheap. “The quality of your crystal, china, silver and linen,” Koehler confides,

“need not be 57th Street, provided that it seems to be. (Feature one of your grandmother’s own heirloom conversation pieces--obtainable at most thrift shops--in your service.)”

Thanks Granny Good Will, these will do nicely.

And a little priceless pain, never however the deceptive cook’s, provides a lot of cover:

“Searing hot plates contribute more to prestige than searing hot food…. You may choose to omit a warning that plates are hot and let a guest more memorably make the point for all.”

Deceptive delights include “Anonymous Sauce,” “Hors Dervish,” “Hot Market Tip,” “Roastettes ‘Rosser’,” “Sole of Deception FTC,” “Soup ‘Exotic Flavor’,” and “Westporc ‘Connecticut’ with ‘Fairfield Sauce’.” This last is a simple and somewhat ingenious synthesis of three storebought commodities. The mixture of applesauce (find some that is not sweetened or rebel against Madison Avenue and make your own) with horseradish and sour cream (these days perhaps crème fraiche instead or a combination of the two) is an exercise in alchemy versatile enough for just about any iteration of, as Koehler calls it in his text, ‘por(c)(k).’

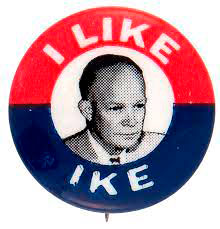

5. Before there was ’Mad Men’ there was a Mad man.

Those ‘roastettes’ are named for Rosser Reeves, an extraordinary and extraordinarily strange genius of a sort. Reeves arrived in New York after flunking out of college, where, due to his year of drinking and carousing, he could not sit his Chemistry final and so submitted a paper he called “Better Living Through Chemistry” instead. Following his firings from a number of respectable positions he turned to advertising and so would become, posthumously, the model for Dan Draper.

Reeves founded the Ted Bates agency along with Bates and became its Chair. “Better Living Through Chemistry” went from the title of a rebellious prank to the catchword identified with DuPont until the counterculture hijacked it; DuPont belatedly dumped the slogan during 1985. Before then it was one of many apparently banal but indisputably effective campaigns Reeves would sustain over a storied career.

He disdained funny advertisements because, he insisted, viewers remembered the jokes but not the products they promoted. He was, however, indisputably innovative, the first to grasp the power of television and to embrace animation as an effective persuasive tool.

His slogans became ubiquitous. For M&M candies, “Melts in your mouth, not in your hand;” for Bic pens, “It writes first time, every time;” for Anacin the grating but memorable “Pressure. Tension. Pain” and “Simple. Nervous. Tension” followed by the punch “Kills headaches fast.”

Reeves coined “I like Ike” and ran all his advertising for the 1952 presidential campaign. He would retire early in golden cuffs but returned to advertising upon the expiration of his noncompetition clause with a brash startup that challenged the established industry. It was an immediate success.

In the interim he wrote poetry (it was published in various media, including a science fiction magazine, invested ingeniously enough to collect precious gems (donating his ‘Reeves Ruby’ to the Smithsonian) and retreated for awhile to his estate in Jamaica.

Reeves espoused his theory of the “Unique Selling Proposition,” or USP, in reality a series of postulates he described in detail with Reality in Advertising, which first appeared the year before Madison Avenue. Reality would prove so influential that six decades on it remains a standard text at the Harvard Business School.

At this writing it remains a mystery whether Reeves liked roastettes or for that matter lamb chops or lamb in any guise; perhaps the association by Koehler of adman and beast is among the misdirective deceptions he devised.

6. Too much deception is never enough.

“Status Stew,” a simple but more than satisfying and, naturally in this unnatural world, expensive braise of beef, specifies the same bottle of expensive Beaujolais you intend to serve your guests, although in our own view it would not in fact be at all deplorable to take the cheating a stage further and use something serviceably cheaper. Just do not show the guests that label.

Some of the recipes, especially those for beef, lamb and pork, along with the Dervish, a disguise for sardine and chutney on dark bread, bear an unmistakably British cast. Back in ’62, British food had not just managed to survive in Manhattan; it also could confer prestige.

Several dishes take deception to a second level. With “Steak ‘Nature in the Raw is Seldom Mild’,” paradox prevails once more. By another name steak tartare, “this elegant raw ground steak experience” requires neither cooking nor consumption to enhance the status of its creator:

“Many people won’t eat it, but in not doing so are embarrassed at their own gaucherie, which accrues to the chic of the chef. And, while the dish requires no cooking, and next to no preparation, it nevertheless helps paint your culinary lily: for though anyone can see no one cooked it, he also believes only a consummate cook would serve it.”

To delve deeper, into metadeception, Koehler suggests, especially if the host worries about his guests going hungry, offering them an equally unpalatable alternative, “Jellied Pigs Feete Cone & Belding;” “with luck no one will touch it.” He offers a complicated, time consuming recipe that he invites his reader to ignore because “you can probably prevail upon the chef of a nearby French restaurant to prepare it for you and still take all the credit.”

7. A forgotten icon addresses the brave new kitchens of postwar Britain.

The omelet looms larger (or does it?) to begin Time is of the Essence, which appeared in London a year earlier than Madison Avenue in New York. Time opens in opposition to the premise of Madison Avenue, from the perspective of a professional private cook and the assumption that cost is a consideration. Its benevolently atmospheric cast is typical of a generous Mrs. Ayrton:

“Time is a much more limiting factor in cooking than money. For example, the most expensive raw ingredients in the world, laid out before the greatest chef, will not help him if he must serve a meal in ten minutes and has only a whole salmon, a 10-lb. sirloin, cream, mushrooms, truffles, potatoes, eggs, a live lobster, onions, strawberries and asparagus out of season; and a bottle of brandy. In ten minutes his master must eat, because in twenty he must get into his car and drive to the airport for the night flight to Rome. What will the chef make of all that wonderful raw food? What can he make?”

The answer, to Mrs. Ayrton, is apparent:

“he will probably ignore salmon, sirloin, lobster, truffles, potatoes, onions and asparagus. Quickly, deftly (and very calmly), he will heat some butter in a pan, slice some mushrooms into it, beat and season his eggs while the mushrooms sauté and make a superb mushroom omelet.” (emphasis in original)

To finish, the cook will have cored and sugared the strawberries before bathing them with a film of the brandy; good fast food all around.

8. An elliptical feminist.

While Mrs. Ayrton applauds his hypothetical improvisation, the limited options available to the cook in question could have been expanded by reference to Time is of the Essence, a guide to larder management in the service of versatile efficiency. By 1961 women had entered the British workforce in unprecedented numbers and found themselves strapped for time in a society that still expected them to perform all domestic duties. Mrs. Ayrton, who displayed great empathy and curiosity about the human condition in all its aspects, created Time to serve a specific, emergent need. The book is neither hectoring nor hortatory. It is gently sympathetic, at times almost confidential, and suffused with good will.

The light touch of her writing emphasizes organization but never in Stakhanovite terms. She therefore includes a section “designed to help someone who is working every day and prefers, as far as possible, to do all her housekeeping, thinking and shopping for the coming week, on Saturday.”

The precision of the passage is noteworthy in its respectful tone (“designed to help,” not hector) and pragmatic approach (“as far as possible”). By no means a feminist in the postmodern sense (her mixed grill for example “is designed particularly to have a masculine appeal”), Mrs. Ayrton however assumes that her reader has as lively an intelligence as she does, with the explicit recognition that the contemplative process of thought is paramount to succeeding with the endless cycle of shopping, cooking and cleaning superimposed, and an imposition it was, on a steady job.

Her approach arguably was a radical departure from contemporaneous authors of domestic management manuals, all of them inevitably, and many of them in a patronizing tone, aimed at women.

9. The culinary calculus.

The format of Time groups recipes across a culinary slide rule calculating times combined with cost. Mrs. Ayrton describes “complete meals which can be prepared in ten minutes, fifteen, twenty, thirty, and forty-five minutes;” once again note the elegant precision of the prose. Each menu “includes a detailed shopping list” and each of the five timeframes offers “cheap, medium priced and rather expensive and grand menus:”

“Menus, notes and recipes with lists of ingredients, unless these are obvious from shopping lists, are given in parallel, so that all you need to know can be taken in at a glance.”

Armed in advance with the prizes from her Saturday shopping expedition, the harried cook has other options as well. “Long-cooking dishes” are not disqualified from consideration when time is of the essence because

“they may be prepared the night before and placed in the oven in the morning with the heat turned to the lowest possible,” 100° Fahrenheit; Celsius remained a ways away from the British consciousness, “and left all day until you return in the evening, when it should be perfectly cooked, hot and appetizing and ready to eat except for checking the seasoning and laying the table.”

Alternatively, more common sense in the kitchen, cook any of these casseroles--ranged in the customary manner of Time from cheap through midpriced to more expensive--for three or four hours at 250° or so.

10. A contrasting code of equipment.

In common with Koehler Mrs. Ayrton recognizes the constraints that hamper her readers but because she actually is interested in teaching them a broad range of preparations diverges from his acute minimalism and in contrast to him assumes those readers are women:

“No one can cook well and quickly unless her kitchen is well arranged and fully equipped. If you live in a rented flat or in rooms, you cannot always have the arrangement or the major equipment of your choice, but you can at least buy extra saucepans and a really heavy frying-pan.”

A colander and strainer she also considers essential, along with the now obsolete “Moulin for purées, etc.” and “Small herb chopper.” The archaism should be forgiven because after all fifty years have passed since the publication of Time.

Mrs. Ayrton requires two pages to specify an extensive ‘store cupboard’ that includes now fashionable canned fish along with unfashionable canned fruit and peas. These last, however, are not bad. Instead they are for practical purposes a different species altogether from the frozen peas that now usually surpass ‘fresh’ ones in sparkle. Mrs. Ayrton also suggests using frozen peas and other vegetables, a relative newcomer to storage food at the time.

11. An omelet so English it is not actually an omelet… or is it?

Each of her two omelets, which in common with Breaux she spells ‘omelette,’ supports a ten minute meal; one of them also slots into a sixth category, of meals based on “Once-a-Week Shopping,” the Saturday spree, that also take different amounts of time. The one with the omelet takes about twenty five minutes.

Koehler, had he known about it, would have been happy to include one of the Ayrton omelets in his selection of deceptions because she includes a stern warning to avoid the traditional technique that defeats the unskilled cook: “Do not attempt to fold” your omelet. Instead, Mrs. Ayrton browns her eggs in their frying pan under a broiler or, to be British, grill.

The technique, far from cheating, is elegant enough for the most elegant if not king of ‘omelets,’ the Arnold Bennett. Unlike most distinctive dishes its originators and origin are more or less uncontested. Bennett wrote Imperial Palace, his novel about a hotel similar to the Savoy while living there during 1929 and 1930. He liked smoked haddock and eggs, and smoked haddock with eggs, and became friendly with Jean Baptiste Virlogeux, the chef at the storied Savoy Grill.

Virlogeux created the Omelet Arnold Bennett, basically a smoked haddock omelet incorporating both hollandaise and Mornay, for his friend, either in 1929 simply because he knew Bennett would like it, or in 1930 for the same reason but as thanks to Bennett for basing a character in the novel on him. His omelet has appeared on the menu of the Savoy Grill in one form or another--a lot of variations exist--ever since.

Mrs. Ayrton’s not quite ten minute editions of omelets both are “substantial” and “much more filling than an ordinary omelette” but parenthetically

“can only be made in 10 min.s if you have kept 6-8 partly-boiled potatoes over from a previous cooking. Very good if potatoes are omitted but of course less substantial.”

This kind of aside recurs throughout Time. One of its principal precepts is preparation, so the assiduous reader will have read the section on “Once-a-Week Potato Peeling and Boiling” and parboiled some spare potatoes the Saturday before cooking the omelet. The recipe serves six so the original potatoes in question must have been small.

The very elegant Omelette Arnold Bennett

Mrs. Ayrton adds the precooked potato to onion, bacon and cubes of bread fried in bacon or pork fat for this extremely British dish which, since it is not tipped, flipped and folded, is really not an omelet at all. “The crisp bread cubes,” as Mrs. Ayrton confides, “are very good.”

The Spanish variation adds green bell pepper, tomato and the options of herbs or mushrooms but gets flipped like the frittata it resembles instead of visiting the grill, so requires a little more skill. “It is,” as Mrs. Ayrton notes, “good served with cheese or tomato sauce,” which recipes however appear nowhere in Time, a rare oversight from its meticulous creator.

In this case less is more. Other than the optional mushrooms the ‘Spanish’ additions do not do much for the British base, which when lapped with the cheese sauce is even better and more substantial still.

12. The English tradition, streamlined.

“Almost all simple English dishes which can be quickly cooked,” Mrs. Ayrton declares at the dawn of Time, “belong to the traditional English breakfast--and most of them can be used as supper or luncheon dishes.” According to her it therefore follows that it amounts to “a waste of space” to provide instruction for their preparation because the process is universally simple and universally known. Even so, a number of reasonably quick traditional English dishes, and some slow cooked ones as well, creep into her text.

Some are oversimple, others more workmanlike than inspired, but for the most part good dishes they are. That mixed grill; skewered lamb, its liver, bacon, mushroom and onion; or liver and bacon represent quick English evergreens for carnivores. There are devils, to transform leftover chicken or turkey into something superior to the original iteration. Five traditional forcemeats also appear, oyster bound with suet among them, to serve with spatchcocked or quickly seared birds along with the classic bread sauce found nowhere without the British Isles. The equally traditional Cauliflower cheese is a hearty alternative to all the meat.

Sandwiches appear only in a section for childrens’ parties (Mrs. Ayrton thought about those too, and about beginning to plan for Christmas months in advance), but the classic English fillings--grated cheese with tomato, cucumber and cream cheese, pastes of fish and meat, egg or Marmite with watercress among them--are equally appropriate for adults, the kind of things English people of a certain age still call nursery food that they refuse to outgrow.

On the slow side Time accommodates casseroles of partridge, game more generally, steak and kidney, a bit sad perhaps deprived as it is of its fluffy pudding coat (it takes too long to steam for the harried cook), jugged hare and the iconic Lancashire hotpot along with beef braised in beer, in fact the Sussex stewed steak that both Elizabeth David and Jane Grigson would revive in the following decade.

13. The indispensable dinner.

And so to Sunday lunch, something hard to build in a flash but too important a ritual to omit in the England of 1961. Now, against odds once again, all that is old becomes new in this era that yearns for comfort. If the plans Mrs. Ayrton present are not quite fast they are faster than most methods but no less effective for that. The key is the addition of dripping to the pan and an oven cranked to 450°, a good way to roast beef whether or not time is of the essence. The potatoes roast in the pan with the meat while the cook prepares her cauliflower and the Yorkshire pudding. For dessert she could choose from a treacle tart or the apple and raisin alternative Mrs. Ayrton recommends for the meal. Completing this particular dance, some of the leftover beef combined with hardcooked egg supports a savory English style curry on a worknight later in the week.

Time is of the Essence is an eccentric enough artifact to qualify as an Occasional Miscellany but also retains an appealing utility. The creative cook need only adapt its approach to our own, straitened, pandemic world in which it has been prudent to minimize expeditions to the grocery store.

Thanks once again to Mrs. Ayrton, this time for something timebound but also timeless and in its way timely. And to Koehler, whose sense of humor endures, so much so that Madison Avenue still induces laughter and, side effect, produces those very good surprises for the table, and even to Daisy Breaux, who despite her foibles remains a model of resilient good cheer.