An Now For Something Completely Different: The British Tradition of The Savory Pie

1. Lamentations.

During the 1970s, two of England’s greatest food writers sounded similar notes. Each was alarmed that the decline of English cookery was so severe that it threatened to extinguish the nation’s traditional foodways.

During the 1970s, two of England’s greatest food writers sounded similar notes. Each was alarmed that the decline of English cookery was so severe that it threatened to extinguish the nation’s traditional foodways.

In 1979, Jane Grigson wrote in English Food of the lamentable “weakness of the domestic tradition that was once our glory.” She attributed the problem not only to “the lack in each of us, of a solid grounding in skill and knowledge about food, where it comes from, how it should be prepared,” but also to the effort of the food industry to flog ‘convenience’ foods. (Grigson xiii) On both grounds Mrs. Grigson prefigures our own debate about obesity, sustainability and the amorality of industrial agriculture.

Four years before Mrs. Grigson, Elisabeth Ayrton had observed that only two of the many traditional English savory pies ‘remained constant.’ They were “the factory-made raised pie, always of pork or veal-and-ham-with-egg, and the steak or chicken pie, also factory made. They are a far and sad cry from the great pies of the past.” (Ayrton 87-88)

From the remove of forty years, nothing in culinary terms sounds sadder than the twentieth century demise of pie. That has changed for much the better in the United Kingdom if not the United States, where the acquaintance of most people to pie is limited entirely to frozen chicken. Exceptions do exist, notably in Buffalo and especially Chicago, but the savory pie remains an outlier.

2. The cause, or causes, of death.

The decline stemmed from overlapping causes in the two countries, if at different times. In the United States but not Britain, “the rise in the nineteenth century of health food fads, led most famously by Sylvester Graham” helped deal the death blow. Graham’s leadership might also be considered infamous; he was the killjoy obsessed with whole grains and vegetables, guilty of inventing the graham cracker as well as baselessly mislabeling piecrust “‘indigestible,’ a term of highest opprobrium for that century.” (Stavely 255-56)

A kind of collective inanity gripped Americans when it came to pie. “The war was waged on pies in general, but surprisingly it was savory pies, not sugar-laden fruit pies, that were particularly targeted.” The ordinarily temperate Sarah Josepha Hale, a popular author of cookbooks, blathered “bluntly that ‘meat pies… should never be made.’” (Stavely 256)

Keith Stavely and Kathleen Fitzgerald wryly note in Northern Hospitality that in common with

“many American dietary fashions, this anti-pie campaign, waged by the same trendsetters who advocated eating beefsteaks for breakfast, now serves merely to point up our paradoxical history as ill-informed consumers.” (Stavely 256)

Even in a nation gripped by culinary hysteria, however, you cannot fool all of the people all of the time. A better reason did exist for the triumph of the fanatics: “In truth, pies in this country were often so poorly made that disapproval of them on health grounds by the day’s nutrition experts merely confirmed the public’s suspicions based on direct experience.” (Stavely 256)

Even in a nation gripped by culinary hysteria, however, you cannot fool all of the people all of the time. A better reason did exist for the triumph of the fanatics: “In truth, pies in this country were often so poorly made that disapproval of them on health grounds by the day’s nutrition experts merely confirmed the public’s suspicions based on direct experience.” (Stavely 256)

The abandonment of pie served a practical master too in the guise of sloth. Although Elisabeth Ayrton’s directive (“Do not be afraid of making pastry”) is reasonable enough, the fear is, and was, real. “Many cooks, then as now daunted by pie-making, simply abandoned the whole exercise.” (Ayrton 90; Stavely 256)

Nonetheless, as we may see, savory pie struggled on in the culinary imagination of Americans and, in the Editor’s own experience, the New England kitchen, both within the region and in its continental diaspora.

As a pertinent aside, the narrative that Stavely and Fitzgerald provide about the death of savory pie in America is anomalous because its chapter alone among the fourteen of Northern Hospitality is not extensively annotated: In fact, it has no endnotes at all. The co-authors, however, are nothing if not reliable, even trustworthy, and the Editor has no reason to question their analysis.

Conventional wisdom ascribes the decline of cooking skills earliest and most often to the British, but savory pie itself represents an anomaly. The ability to assemble pies lingered considerably longer in Britain, at least until the 1920s, than in America.

In contrast to conditions in the United States, the decline of piemaking in Britain was not a particular culinary phenomenon but rather mirrored the decline of the British kitchen more generally, a phenomenon of numerous causes.

They include nineteenth century urban dislocation and deprivation among the working class, the Victorian cult of feminine gentility that severed middle class women from their own kitchens, an Edwardian upperclass mania for French, or rather bad pseudo-French food, and of course the elephant in the historical room, fifteen years of rationing triggered by the Second World War that also, and not incidentally, bankrupted Britain.

3. Conception.

Happily enough pie has regained a certain primacy there, where it all began (most of it anyway) and most famously flourished. According to Alan Davidson in The Oxford Companion to Food :

“Many languages lack a truly equivalent word, since pies, in the Anglo-American sense of the word, are indigenous to Europe, especially Central and Northern Europe, and occur elsewhere only as introduced dishes. It is in North America their introduction has been [or at least had been] most extensive.” (Davidson 602)

The Eurocentricy of protopies is a bit of a surprise given their original purpose. Until the advent of mass-produced domestic kitchen equipment, canning, railroads, refrigeration and latterly plastic, piecrust served a dual function as preservative and container, the ovenproof Ziploc bag or Tupperware of its time.

Fireproof pottery and then metal cooking vessels were scarce and expensive for centuries; the crust of a pie was an economical expedient, and the pastry of some early ‘pies’ was not even edible. The use of inedible paste had not died off entirely in England by 1975, when Mrs. Ayrton published a recipe for baking ham encased like a broken limb in a simple cast of flour and water. The method survives in at least one American kitchen, a favorite of the Editor because it allows the flavor of a good big ham to develop without desiccation.

Cold raised pie at home.

The practice was all the more practical before ovens had thermostats and temperature controls. As Stavely and Fitzgerald explain: “In effect, the pastry became an oven, ensuring moderate heat thanks to its insulating properties.” (Stavely 261)

Edible crusts, however did become the norm, both because they taste good and because they conferred convenience. The use of forks was not widespread until the eighteenth century in the British Isles, so the preparation of something handheld like a cold raised pie was the best available choice for all but the most affluent households.

Cold raised pies, oddly enough given their universal utility an innovation confined to the British tradition, bind their fillings in a rich broth that jells as it cools. Much like the clarified butter used to seal potted meats and other traditional British savory preserves, its embrace kept the contents of a pie edible for a longer time than the unrefrigerated filling alone could survive.

Hot pies are at least as venerable. According to Laura Mason and Catherine Brown in their indispensable Traditional Foods of Britain , first published during 1999:

“Hot pies were a food of London and other big cities [in the British Isles], hawked through the streets by itinerants whose individual cries have been celebrated or excoriated since the fifteenth century. Beef, mutton, eels and fruit are all recorded as fillings.” (Mason & Brown 214)

Fish spoils faster and so fish pies required the butter, a stronger sealant than jellied stock, used for potted foods instead. (Wilson 42) Birds or beast embalmed in the same manner would keep for weeks.

Cries of London.

Cries of London.

The other savory pies that evolved as we know them also evolved in Britain. Gilly Lehmann brooks no equivocation in The British Housewife : “By the middle of the seventeenth century, pies had become a peculiarly English specialty; even the French were prepared to concede superiority.” By the early eighteenth century, pies “had a long and honourable past, and were thus less susceptible to foreign influence than the made dishes at which the French were held to excel.” (Lehmann 194)

The term itself derives, possibly, from an unexpected English word, as Davidson explains:

“The derivation of the word may be from magpie, shortened to ‘pie.’ The explanation offered in favour of this is that the magpie collects a variety of things, and it was an essential feature of early pies that they contained a variety of ingredients. So they did. But this aspect of the meaning has been lost, and nowadays one can have pies with only one important ingredient…. ” (Davidson 603)

4. Magpies at work in the kitchen.

The ingredients baked into the early pies are nearly as numerous as the range of foodstuffs and spice characteristic of the British kitchen. And as a great trading nation, Britain enjoyed a broad range of them from across the globe. A recipe for stock alone, or ‘lear’ like this one from 1730 by ‘E. Smith,’ could include

“Claret, Gravy, Oyster Liquor, two or three Anchovies, a faggot of sweet Herbs and an Onion; boil[ed] up and thicken[ed] with brown Butter, then pour[ed] into your savoury Pies when called for.” (Smith 4)

In Smith’s hands his lear was versatile; one of its tasks was binding an old-fashioned pie of the day, the rather baroque battalia. Its name “probably derives from the medieval Latin term for samplers sewn by nuns--beatillae--meaning ‘small blessed articles.’” (Stavely 258) The diminutive entails no small irony.

To construct the ‘small’ blessed article, Smith instructs the reader to:

“Take four small Chickens, four squab Pigeons, four sucking Rabbets; cut them in pieces, season them with savoury Spice; and lay ‘em in the Pye, with four Sweetbreads sliced, and as many Sheep’s tongues, two shiver’d Palates, two pair of Lamb-stones, twenty or thirty Coxcombs, with savoury Balls and Oysters.”

This concatenation was enriched with butter and bound with our lear. (Smith 8-9) Incidentally neither Claret, which is red Bordeaux, nor the anchovy, preserved in barrels by fermentation and imported from the Mediterranean, is indigenous to Britain.

Readers may wonder about the bones. The recipe includes no mention of them because, in contrast to most modern practice, many recipes published as late as the twentieth century show no compunction about encasing unboned joints of poultry and small game in pie (others bone and even mince the meat of the birds; Wilson 135-36). The cooks following these recipes were not squeamish or lazy; there was method to their practice. We might follow their lead because simmered bones add heft and flavor to any dish.

Palates and coxcombs are as they sound. Sheep-stones are balls and savoury balls are made of forcemeat, a sort of cross between a dumpling and stuffing. Typical constituents of forcemeat could include breadcrumbs; suet and egg to leaven and bind; bacon; cayenne; lemon zest; and combinations of herbs. In other words forcemeat is a wonderful thing that requires revival.

5. Complexity and contradiction in construction.

In the same year as Mrs. Smith described her battalia, Charles Carter published The Complete Practical COOK: Or, A New SYSTEM Of the Whole Art and Mystery of COOKERY. Being a Select Collection of Above Five Hundred RECIPES for Dressing, after the most Curious and Elegant Manner ( as well FOREIGN as ENGLISH ) all Kinds of Flesh, Fish, Fowl, &c. As also DIRECTIONS to make all Sorts of excellent Pottages and Soups, fine Pastry, both sweet and savoury, delicate Puddings, exquisite Sauces , and rich Jellies. With the best RULES for PRESERVING, POTTING, PICKLING &c.

Modern authors unfortunately have lost Carter’s facility for description: The entire title is even longer. His prolixity gives us an insight into his perch on the spectrum of eighteenth century English foodways. It was progressive, as indicated by his use of ‘recipes’ instead of the older ‘receipts’ to describe its dishes. So was his strict separation of savory and sweet pastry; the distinction was then just beginning to supplant the medieval practice of combining the two.

Within the text he highlights ‘savoury baked meats’ in their own chapter that also covers game, and sets both cold savory meat and baked savory fish pies in their own chapters as well. Altogether Carter presents fifty recipes for savory pies.

He also was retrograde, which his title does not reveal, in his inclusion of some dozen sweet pie recipes (but less than a quarter as many as their savory counterparts and none incorporating game) for fish, poultry and meats; his enthusiasm for adding cloves, ginger and mace together to savory dishes; and his inclusion, like Mrs. Smith, of battalia, a preparation which would not survive the century. And yet Carter’s version appears more modern than hers in its incorporation of vegetables:

“A Battalia Pie is made of Rabbets or Chickens cut into Pieces or large Quarters; raise a Coffin,” or piecase, “with eight Rounds, and first lay in your Chickens or Rabbets, then lay in scalded Lettice cut in Quarters, lay in Chestnuts blanch’d, lay in Sausages, some Sweetbreads and Pallats flic’d,” that is flayed, or sliced, “some Oysters set and blanch’d, and some Lumps of Marrow roll’d in Eggs, some Yolks of Eggs hard, some Morelles and Mushrooms, and season all as you go; lay some Slices of Bacon on the Top, and lay Butter over, and close it, and bake it; then take off the Fat, put in good Gravy,” here again note the more modern usage than Mrs. Smith’s ‘lear,’ “thick Butter, and the juice of an Orange, and serve it.” (Carter 145)

This is hardly a simple let alone practical procedure, but as the extension of Carter’s title indicates, practicality may not be his only concern. It boasts that The Complete Practical COOK , while “ FITTED FOR ALL OCCASIONS ” is intended “ more especially for the most Grand and Sumptuous Entertainments. ”

This is hardly a simple let alone practical procedure, but as the extension of Carter’s title indicates, practicality may not be his only concern. It boasts that The Complete Practical COOK , while “ FITTED FOR ALL OCCASIONS ” is intended “ more especially for the most Grand and Sumptuous Entertainments. ”

Should we believe him? Probably not. Some of his recipes are reasonably practical, while the others may be baubles intended to appeal to the aspirations of his public rather than actual guides to the preparation of food.

Reference to grandeur, like Carter’s boast that he formerly cooked in the kitchens of three peers (Argyle, Cornwallis and Pontefract), and that his recipes had been “Approved by divers of the Prime Nobility” were venerable marketing ploys intended to appeal to the imaginations of the readers he hoped to attract.

All this indicates that Carter stands as a transitional figure who straddles medieval and early modern practice.

To return to pie, his battaglia itself looks like one of the aspirational throwaways in comparison to many of his other, relatively simpler recipes, even if relative is the exemplar of a relative term.

At first sight some of them, had they included measurements, would look familiar to a cook working in subsequent centuries. Carter’s goose pie “Another Way,” for example, sounds both simple and beguiling upon casual review.

It mixes the goose with a forcemeat that amounts to black pudding made with breadcrumbs, marrow and the blood of the goose, seasoned with nutmeg, parsley, thyme and sage. Simple, that is, if you leave the filling at that instead of throwing in “all the rest as before” required for his previous “Green-Goose Pie.” ‘All the rest’ includes asparagus, egg yolks, gooseberries, lettuce, livers, onion, sorrel, spinach, and, in an inconsistent lapse into archaic usage, a dose of ‘leer;’ altogether the kitchen sink.

6. A national dish of lithe lineage.

The battalia did not survive the eighteenth century but pie per se would flourish in the comparatively simpler style that still exists in Britain. As noted, savory pies of all kinds--cold raised ones as well as hot pies sheltered in various other forms of pastry--have enjoyed a British revival since the dark days described by Mrs. Ayrton and Mrs. Grigson.

The marketplace reflects the revival of savory pies in the form of any number of cookbooks devoted exclusively or primarily to them; a set of selected reviews may be found in the critical.

The most famous of hot savory pies can appear in very nearly Amish or increasingly complex guise. At its plainest, steak and kidney pie consists of little more than the items in its name. The filling in the recipe from The Official Handbook of the National Training School of Cookery by Edith Clarke in 1915 includes only ‘buttock steak,’ ‘bullock’s kidney,’ salt, pepper and water. By then the venerable compilation had undergone multiple modifications but steak and kidney pie remained a model of constancy.

Mrs. Beeton’s was much the same half a century earlier. By 1974, however, Jane Grigson has added herbs (“Bouquet garni;” an example of the lingering twentieth century British usage of French words to describe English things), mushrooms, onion, oysters, stock and red wine to the mix.

The justly celebrated steak and kidney pie baked at The Guinea, a stunning public house with an eighteenth century aura in a mews abaft Berkeley Square in London is fussier and better still. The formula adds bitter ale (purists will choose Young’s ordinary; The Guinea is tied to the brewer, alas now but virtual but vibrant still) to the stock instead of wine, mushroom ketchup, English mustard, thyme and Worcestershire. The Guinea pie sports the additional attraction of a suet pastry top (but no bottom) crust, which makes the pie easier to assemble, qualifies it as what the Irish call a ciste and renders it even better. The Editor does something similar to the Guinea but cannot resist the oysters that Mrs. Grigson recommends as well.

According to her, this iconic English pie does not, “it seems, go back” so very far; “Mrs. Beeton’s recipe in Household Management of 1859 is the first to add the essential kidney.” (Grigson 243) Notwithstanding the esteem in which the Editor holds all things Grigson, her assertion has proven hard to verify.

Glyn Lloyd-Hughes pushes back the pie eight years, to the publication of The Frugal Cook by ‘E. Carter:’ “Known since 1851.” (Lloyd-Hughes 136)

We have found no earlier text, but other writers ascribe a longer lineage to the dish. In the encyclopedic British Cookery , Lizzie Boyd properly if implicitly finds the filling for steak and kidney pie or pudding interchangeable. She asserts that it is “one of the oldest puddings, the pride and joy of British classic cooking.” (Boyd 321, 322) Puddings have been boiled in Britain for centuries, so her claim pushes the marriage of steak to kidney back hundreds of years.

Mrs. Beeton fowl illustration.

Mason and Brown pick up the thread and proceed to tangle it past repair.

Their Traditional Foods of Britain is an encyclopedic accomplishment but also, weirdly enough, something by turns (mostly) informative and (sometimes) inscrutable. On the subject of steak and kidney the second characteristic holds sway.

First, on pie, Mason and Brown cite the ordinarily authoritative Oxford English Dictionary to say that the “precise combination of steak and kidney… does not seem to be mentioned until early in the 1900s.” (Mason & Brown 215) We already know better, from Mrs. Grigson, who is correct that Mrs. Beeton combined the two in 1859.

Then, in their discussion of the same filling for pudding, Mason and Brown equivocate:

“It is not clear when and where steak and kidney first met in a savoury pudding. Evidence so far discovered points towards the south-east of England in the late eighteenth or early nineteenth centuries.” (Mason & Brown 215)

The do not disclose the nature of this ‘evidence,’ but if the evidence does exist, then it takes no leap of faith to infer that if steak and kidney found itself in a pudding then it also found its way into a pie.

7. Washington slept here; or did he?

Various sources date the combination of steak and kidney to the late eighteenth century, but in North America rather than the environs of Kent and in a pie, not a pudding.

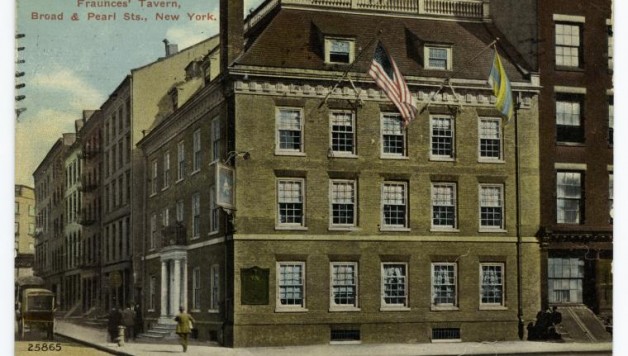

This version of the creation myth sends the couple back about a century before Mrs. Beeton, but provides no source for the serial assertion that George Washington ordered steak and kidney pie, among other foods, at Fraunces Tavern for the officers of the Continental Army and their French ally to celebrate his farewell address to them late in 1783.

The ‘questing feast’ website is typical in linking Washington to the dish but at his Virginia plantation rather than in New York City. “Steak and kidney pie,” according to the site, was among the “[f]avorites of his that appeared on the Mount Vernon table frequently…. Like in England, pies were a favorite food on the early American table, both sweet and savory.” (‘questing feast’)

Manny Howard picks up the thread in an article from Gourmet as recently as 2011. (Howard) In an emerging pattern, neither he nor ‘questing feast’ provides a source for the assertion. A number of periodicals including GQ and The New York Times Magazine have published pieces by Howard so a number of editors have been willing to take his journalism on faith, but maybe when it comes to steak and kidney pie he has recycled conventional wisdom without reflection or research.

For some reason Jessica B. Harris is considered a scholar, and to be fair she is a tenured professor at Queens College of the City University of New York. Queens does wonderful things, like manage the Louis Armstrong House Museum in nearby Corona and operate an exemplary law school concentrating on public service.

Harris, however, has done the same thing in High on the Hog: A Culinary Journey from Africa to America as Howard did at Gourmet.

In discussing Washington’s chief cook, an accomplished slave called Hercules (at one point, according to Harris, he supervised both a German and two French cooks) she concedes that “[n]o recipes attributed to Hercules have been found.” Harris then proceeds to speculate that “he certainly must have been adept at preparing the steak and kidney pie and trifle that were known to be among Washington’s favorites.” (Harris 74)

As we have seen, there is nothing certain about his or any of his contemporary’s expertise with such a pie, and Harris offers no citation for this or any other assertion in High on the Hog ; it has no footnotes or endnotes. Her bibliography includes only a single source on Washington, a short compilation of essays published in 2001 by the Mt. Vernon Ladies Association. Slavery at the Home of George Washington , while a worthy enough example of rigorous historical scholarship, includes nothing about steak and kidney pudding. Harris merely has recycled an apocryphal tale as fact.

In a playful letter from 1779, Washington refers to “beef-steak pies” but not to kidney or steak with kidney. Inviting his correspondent’s wife and her friend to dinner, Washington poses a rhetorical question; “am I not in honor bound to apprise them of their fare? As I hate deception, even where the imagination only is concerned, I will.” (Washington)

He then notes that his current cook--Washington is on campaign and the dinner table will be set near West Point, not at Mt. Vernon, so Hercules is unlikely to run the kitchen--

“[o]f late has had the surprising sagacity to discover, that apples will make pies; and it is a question if, in the violence of his efforts, we do not get one of apples, instead of having both of beef-steaks. If the ladies can put up with such entertainment, and will submit to partake of it on plates, once of tin but now iron (not become so by the labor of scouring), I shall be happy to see them…. ” (Washington)

All of this reinforces Washington’s reputation for honesty and belies his historical reputation as dour and wooden, but none of it establishes an eighteenth century association of steak with kidney.

All of this reinforces Washington’s reputation for honesty and belies his historical reputation as dour and wooden, but none of it establishes an eighteenth century association of steak with kidney.

Even though a manuscript handed down to Martha Washington from her ancestors includes a lot of recipes, we do not know much about Washington’s taste in food.

Martha Washington’s Booke of Cookery contains no recipe for steak and kidney pie (or pudding), although its instructions “to make a pie of seuerall things” include lamb and veal kidney but also “over a score” of other ingredients in addition to seasonings. It is a retrograde recipe for a medieval olio, and demonstrably premodern in its collision of sweet and savory. Coxcombs, palates, sweetbread, tongue, poultry and artichoke (“heartchoke”) join the kidneys, and the olio also encases barberries, gooseberries or grapes, citron, dates and oranges. (Hess 84-85) The Editor has no hesitation in dismissing the manuscript olio as a precursor to steak and kidney pie.

Mrs. Washington, while staunchly conservative in social terms, was not necessarily a reactionary chatelaine instructing Hercules to crank out olios, battalias and other Restoration relics: She had inherited an accretive manuscript that originated in the seventeenth century. In addition, Hercules quite obviously had not trained in the kitchen of a great house kept by any English magnate or at Cordon Bleu. Whatever his level of expertise he therefore was less than unlikely to prepare such elaborate dishes descended from the Court cookery of Stuart or Bourbon.

To return to steak and kidney pie, Stavely and Fitzgerald ignore it in Northern Hospitality. Granted the book addresses the foodways of New England and not New York, but because New York was the less Anglophile of the two in culinary terms, we should expect to find the dish in New England during the period when it was prepared in New York.

Given the breathtaking quality of research that underpins Northern Hospitality , it is permissible to infer that steak and kidney pie did not make much appearance in New England, not in the eighteenth century anyway.

Whatever its date of birth or incarnation, Mrs. Ayrton is right. Steak and kidney “is the best of all savoury pies: an English dish which is [or, in 1975, was] famous all over the world.” (Ayrton 106) Nonetheless it only is primus inter pares, for anyone presented with a raised pork pie would be foolish to refuse a slice.

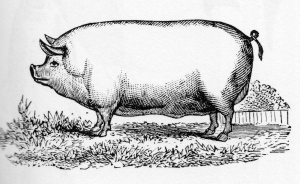

8. Another exemplar.

This most famous of raised pies--the adjective refers to the hot water pastry that must be ‘raised’ when warm by hand, not the provenance of the pig--is a relatively plain one bursting with the flavor of pork. Like Paul Prudhomme, but centuries before his time, its originators in the north of England combined different iterations of the same thing to increase the intensity of the taste. Lard shortens the raised pastry, chunks of shoulder dominate the filling flavored with cured (but not smoked) loin bacon, and pigs’ trotters provide the gel to bind all together.

Paradox too enters play. As with chowder, which uses salt pork to boost the tang of clams, the secret to a good pork pie is something apparently antithetical to its base ingredient. Anchovy paste or sauce, or gentlemen’s relish, provides the anonymous accelerant that takes the taste of pork pie orbital. In the case of pork pie, roles have reversed and the sea accents the shore.

The most famous source of pork pie is Melton Mowbray in Leicestershire, so famous that the European Union has granted the name protected status: Only pies baked in the town itself may bear the descriptive and if they use it may not include artificial color or flavor, or preservatives. According to Glyn Lloyd-Hughes, they always are filled with shredded rather than minced pork but the Editor has come across Melton Mowbray pies with meat cut into chunks, but never ground or minced. (Lloyd-Hughes 135)

As of 2010, according to Lloyd-Hughes, “Melton Mowbray Pork Pies are big business--worth something like a million pounds a week.” One traditional pie at least has survived, and thrived. (Lloyd-Hughes 135)

Pie in general is a peculiar exemplar, a dish that elevates something standard to something special, all the way to elegant. Some pie fillings defy existence absent a coating of crust. It is hard, for example, to imagine Philippa Davenport’s sophisticated venison pie stripped of its pastry. The filling itself, which Davenport described in 1980, incorporates not just the deer but also lemon juice, mushrooms, prunes and fabulous forcemeat balls fashioned from breadcrumbs bound with egg and suet, then seasoned with mashed anchovy, bacon, lemon zest and parsley.

Pie is versatile. It may mark a special occasion or mask lowly leftovers as creative food for a busy weeknight. Freshen last week’s curry with ginger and citrus or add mushrooms to the remains of a stew, top either with a lid and nobody will be bereft.

Whether or not their reputation for thrift spiraling to stinginess is justified, and most likely it is not, the Scots have taken the recycling of leftovers into pie so far that they have named one. Resurrection pie began as an expedient but before the Second World War had become popular enough to take the transformation to an end in itself.

9. A fable of the resurrection.

In the ghostly Cook o’ the North , which appears to exist only at a handful of scholars’ libraries and as fragments within the compilations of other authors, its ‘editoresses’ Lady Mabel Forbes and Miss Janet Mitchell-Thompson include a Resurrection Pie that relies on raw ingredients rather than remnants. They are “[e]qual portions of liver, steak and rabbit; two or three rashers of bacon, onions, potatoes, pepper and salt.”

Assembly of the pie is a simple operation that layers the ingredients twice; meat then bacon, then onion and potato before topping them with a ‘lid,’ presumably of pastry. That, anyway, is how the Editor prepares the pie, simple Scots cookery at its best. Resurrection Pie is, or was, an important enough item for the celebrated André Simon to include in his History of Gastronomy. No particular Scotophile, Simon hardly tilted his History to North Britain so considered the pie something significant, like pot au feu or a good ragout.

Resurrection is as good a place as any to conclude a meditation on savory pie because, we hope, its second ascent continues apace.

Recipes for all manner of savory pie appear in the practical.

Pie guys at Pieminster. They get it.

Note:

The Editor is particularly indebted to Keith Stavely and Kathleen Fitzgerald for their treatment of traditional English pies in Chapter Ten of Northern Hospitality.

Sources:

Anon., “George Washington’s Favorite Foods,” www.thequestingfeast.com/articles/George_Washington _Food.html (accessed 30 July 2014)

Elisabeth Ayrton, The Cookery of England (London 1975)

Isabella Beeton, Beeton’s Book of Household Management (London 1861)

Edith Clarke, The Official Handbook of the National Training School of Cookery (London 1915)

Philippa Davenport, 100 Dishes Made Easy (London 1980)

Alan Davidson, The Oxford Companion to Food (Oxford 1999)

Henry Russell Drowne, The Story of Fraunces Tavern (New York 1966; orig. publ. 1919)

Lady Mabel Forbes and Miss Janet Mitchell-Thompson, Cook o’ the North (Aberdeen 1936)

Jane Grigson, English Food (London 1979)

Jessica B. Harris, High on the Hog: A Culinary Journey from Africa to America (New York 2012)

Karen Hess (ed. & annotator), Martha Washington’s Booke of Cookery (New York 1981)

Manny Howard, “Local Food Goes Loco,” Gourmet (30 March 2011)

Gilly Lehmann, The British Housewife (Totnes, Devon 2003)

Glyn Lloyd-Hughes, The Foods of England (Adlington, Lancs 2010)

Laura Mason & Catherine Brown, Traditional Foods of Britain: An Inventory (Totnes, Devon 1999)

Philip Schwartz (ed.), Slavery at the Home of George Washington (Mt. Vernon VA 2001)

André Simon, A Concise History of Gastronomy (Woodstock NY 1981; orig. Publ. New York 1952)

E. Smith, The Compleat Housewife: Or, Accomplish’d Gentlewoman’s Companion (4th ed. London 1730)

Stavely & Kathleen Fitzgerald, Northern Hospitality: Cooking by the Book in New England (Amherst 2011)

Corres. of George Washington to Dr. John Cochran (16 August 1779)