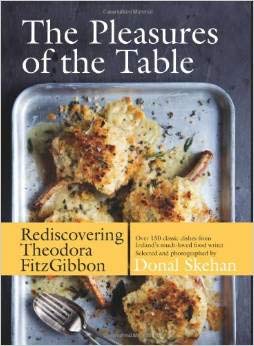

A boyish celebrity chef celebrates an illustrious forbear in The Pleasures of the Table: Rediscovering Theodora FitzGibbon by Donal Skehan.

1. Another train to Clarksdale?

The career trajectory of Donal Skehan appears at first glance unlikely.

His initial claim to fame was nothing if not awful. In 2006 at the age of twenty he became affiliated with the speculative investment project “Streetwise.” A marketing vehicle like the Monkees, One Direction or the Spice Girls, the boy band included singers--nobody could play an instrument--from Ireland, Britain and Sweden. Members of such an enterprise must be telegenic (one of the “Streetwize” participants bears a passing resemblance to Matt Damon, and Skehan himself is no slouch in the appearance department) and unselfconscious, not to say unembarrassable. All of them are fungible. Musical talent is neither a disqualification nor a necessity.

If the investment pays off, the backers and sometimes the band itself may become wealthy, but “Streetwize” did not prove lucrative. The band reached number one on the Irish charts with each of two singles so must have sold a few hundred copies of its ‘work.’ Nonetheless a disillusioned Skehan and another Irish singer left the venture within a year, and were promptly replaced by an American and a Venezuelan.

After ditching “Streetwize,” Skehan competed for the Irish slot in the ludicrous Eurosong contest in 2008 but the honor went to “Dustin the Turkey” instead. A year earlier, however, he had started blogging.

2. A boy makes good from good mood food…

His goodmoodfoodblog.com led to a publishing contract for Good Mood Food , a slight cookbook featuring sophisticated things like sandwiches, vegetables and cupcakes. These ‘recipes’ require between fifteen and twenty minutes to prepare. Skehan has confessed during interviews that he hoped to keep the book healthy but included the sweet stuff because it is the most popular food content on the net and he ‘had to compete.’

Success followed fast. Skehan landed a cooking program on Irish television, “Kitchen Hero,” and several tie-in books sharing the name of the popular show followed suit. By 2012 he was a cohost and judge on the BBC hit “Junior MasterChef.” By the next year Skehan had published four cookbooks and founded Skoff Pies, baker of handheld packaged pies for the Irish market. Last year he launched Feast , a quarterly “dinner journal.”

3 …and becomes a brand.

His blog has become donalskehan.com. The substance of the site is unremarkable if typical of the genre; its frantic layout and brief pieces pander to the arrested attention span of the times. Recipes have not traveled far from their precursors at goodmoodfood and are for the most part mundane. The blog itself features lots of smiley headshots of its author, an abundance of exclamation points!, CAPITAL LETTERS, abrupt ‘vlogs’ (“I decided I would record what I’m up to each week and share it with you”) and listicles. The top ten traditional Irish recipes allegedly include roast lamb with rosemary and garlic, chowder, apple crumble (“one of my most favourite desserts of all time”) and that staple of the ancient Gaels, a hamburger. Perhaps an accuracy index of 60% is not bad as these things go.

From all this it should be evident that Skehan or his advisers are good at marketing. He parlayed his blip of celebrity with “Streetwize” into a spot with Irish Eurosong, and used the exposure the competition gave him to promote blog and then book. In the process he appeared as a guest on various cooking programs and used those appearances in turn to earn his own show.

Skehan has become a brand, something like an Irish Jamie Oliver lite, and it is not difficult to discern why. His manner is perpetually cheerful and he retains a boyish charm. Skehan’s neoteny remains arresting at the age of twenty-eight; the boy band backers knew their business.

4. Finis origine pendet.

None of this explains the smooth shift from pop understar to celebrity cook. What does explain it is the family business, a Dublin food distributor called Fresh Cut Food Services. His parents, originally wholesalers of produce, have added to the original business to become a ‘provider of food solutions.’ Now they also sell prepared portions of meat, fruit salad, quiches, terrines and the like to institutional kitchens. Fresh Cut Food also produces Skehan’s Skoff line of pies. Cross-marketing, whether in the service of cabbages or celebrity, flows in the family blood.

5. A turn toward substance.

Although we can find not fault with what Skehan does, his lines of work are not something ordinarily of interest at britishfoodinamerica. In 2013, however, something interesting did happen to him. He discovered the redoubtable Theodora FitzGibbon, or rather her writing.

Based on what went before, this was an unexpected development that turns out to be most welcome. Skehan has compiled some one hundred fifty recipes and published them as The Pleasures of the Table: Rediscovering Theodora FitzGibbon.

This interest in his subject is commendable, and unlikely to result in calculation aimed at burnishing the Skehan brand. His readers will not have heard of her, and even in the postsectarian precincts of Ireland an Ascendancy figure like Mrs. FitzGibbon, beloved as she may have been of Irish Times readers (themselves historically Unionist), does not leap into the collective consciousness of the island. It appears that curiosity, conviction and conscience have overtaken our benign boyband buccaneer.

Nobody can complain about the selection of recipes in The Pleasures of the Table. Skehan has chosen well, both in terms of the dishes described and the wryness around them from Mrs. FitzGibbon herself. On, for example, the absence of offal:

“When I remarked to the butcher that all the animals seemed to be born without tongues, tails, hearts, kidneys, liver or balls, he winked at me, a great arm went under the counter, and flung up a half-frozen oxtail.” (Skehan 43)

We learn it was only from “about 1746 that rice was used a lot in Irish cooking” and that A Shilling Cookery for the People by Alexis Soyer, the celebrated French Anglophile and chef from the Reform Club in London, “circulated in many parts of Ireland,” an indication that the Irish dishes found even in the nineteenth century were as much the dishes people in Ireland adopted rather than ones that originated there.

Among Skehan’s selection of wonderful FitzGibbon recipes; beets in orange sauce; boxty of course, and fadge; devilled crab; the essential Dublin coddle; Soyer’s convent eggs; ham cooked in Guinness for service with an astounding sauce of apples, celery and ginger; oatmeal and bacon pancakes, from a 1717 County Longford manuscript; pork ciste; a delightful mousse based on ice cream called ‘Café Liégois;’ many many more, rescue archeology of a high order.

Gill & Macmillan, Mrs. FitzGibbon’s publisher, has done him proud. The book is a beautiful edition, replete with food porn taken by Skehan himself, a workmanlike photographer, laced with wonderful photographs of the glamorous FitzGibbon and complete with a ribbony bookmark.

6. The catalog of omissions.

There are problems with the book. Skehan’s pedestrian prose is serviceable enough but irksome. Fortunately there is little of it because he has made the judicious decision to let Mrs. FitzGibbon speak for herself. The Pleasures of the Table itself is but an arbitrary name--it does not appear anywhere in the FitzGibbon canon--and includes only two illustrations of pages from The Irish Times , but the recipes are otherwise absent from the book while the reproductions themselves are too small to read. That is a shame. The Irish Times recipes for pressed beef flank or devilled steak and kidney casserole appear enticing indeed. Sloppy: A little more attention to detail would have gone a long way.

Skehan is no scholar--he dropped out of high school--and it shows. He has not bothered to spend time at a decent library or the archive of the Irish Times , where Mrs. FitzGibbon held down a legendary cooking column for some two decades. Instead, and in common with too broad a band of his demographic, Skehan has only surfed the net: “After some bargain-hunting online, I managed to order second-hand copies of the vast majority of her books,” but which ones? Was his a random selection? He also “pored over the many newspaper clippings” his grandmother had saved from the Irish Times , but does not disclose how many he found, which ones or when they appeared in print. (Skehan xv)

Skehan has no excuse; he lives in Howth on the border of Dublin and George Morrison, Mrs. FitzGibbon’s second husband, agreed to meet with him and bless the undertaking. Did he enter the widower’s library?

Ironically enough, Skehan recognizes that addiction to the internet explains the obscurity of Mrs. Fitzgibbon’s work: “Her popularity was in an Ireland far before my world of social media and food blogs, which means her recipes have stayed solely and exclusively [Ed.’s note: And so redundantly; better editing please.] in her printed publications” which, incidentally and inexcusably, remain out of print. (Skehan xv)

Nor does Skehan disclose the origin of any recipe, a source of great frustration. Where, for example, did he find her wonderful Chicken Biryani or her pair of Lahori recipes? From The Irish Times ? We cannot know, for while Mrs. FitzGibbon wrote cookbooks on the traditional foods of Britain and of Ireland, on Scotland and all the regions of England, on Wales and Paris and Rome, she did not publish an Indian cookbook.

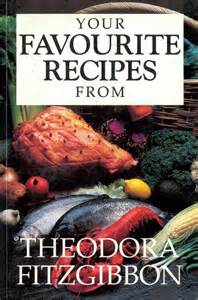

Also absent; a bibliography, although according to the British website of Gill & Macmillan (but not its Irish site), each recipe originates from one of only three sources. They are listed as Irish Traditional Food along with the extremely obscure Theodora FitzGibbon’s Cookery Book and Your Favourite Recipes , this last a selection from her column at The Irish Times. This disclosure unaccountably contradicts Skehan’s claim that he plowed through most of Mrs. FitzGibbon’s publications and all those Irish Times clippings.

The omitted information is particularly problematic in the context of so prolific an author as Mrs. FitzGibbon, who wrote more than thirty books, including two racy and eventful autobiographies in addition to the food column, unless Skehan did consult only the three volumes disclosed by his publisher. Even then it would be nice to know where each recipe originated.

Skehan also might have let us know more about her. He and the celebrities whose too brief tributes preface the recipes do claim Mrs. FitzGibbon for Ireland, which is not strictly accurate but probably fair: She would complain on moving to Ireland that despite her considerable success the English never had understood her.

7. A remarkable, and remarkably cosmopolitan, woman.

This remarkable woman personified the cultural exchange between nations of the British Isles and Empire during the first half of the twentieth century.

As her books invariably note, Mrs. FitzGibbon was “born in London of Irish parents.” Her father, an epic rogue, produced a number of children on both islands, each by a different mother, but spent most of his time as a civil servant posted to India. He would arrive in England unannounced to whisk young Theodora off at irregular intervals to the crumbling family estate in Ireland.

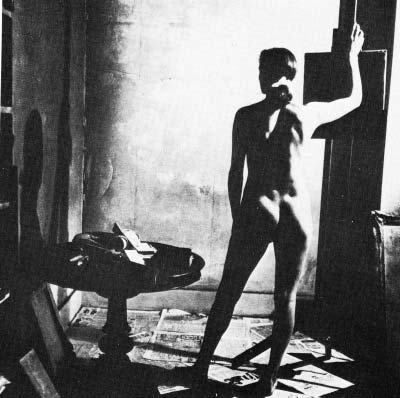

Mrs. FitzGibbon at work.

Mrs. FitzGibbon at work.

She was not only an esteemed cook and author but also took turns as a model (fashion and nude), West End actress, editor (of others’ cookery columns at the Irish Times ), firewatcher (nearly killed in the London blitz) and muse. Between the wars in Paris she ran with a crowd that included Ernst, Giacometti, Mesens and Picasso. Mrs. FitzGibbon also belonged to the wartime Fitzrovia set. Dylan and Caitlin Thomas were her friends, and she knew Francis Bacon, who kept copies of her books, Norman Douglas and Philip Toynbee among other cultural notables. After the war she lived in the United States for a time and, eventually, settled in Ireland.

In the Editor’s estimation Theodora FitzGibbon is one of the greatest, not only of Irish or British but of all writers on food. Skehan’s professed admiration is more than justified, but he ought to have dug a little deeper and thought a lot more about his subject.

8. Buy the book.

Nothing should prevent another author with access to Irish Times editions of the FitzGibbon era from compiling a book of her cookery columns. Meanwhile The Pleasures of the Table at least represents a modest step toward the reassessment of a fascinating figure and stands as a decent place to begin a closer acquaintance with her.

A selection of Theodora FitzGibbon’s recipes appears in the practical.