Confusion now has made her masterpiece: Eugene Walter, his cult of Mobilian chaos & some descriptions of southern foodways.

1. A son of lunacy’s county seat.

Eugene Walter has been largely forgotten beyond the boundaries of his native Alabama, and even there his legacy is nearly lost outside his native Mobile. That is odd. He was a fantastical man who lived a fantastical life, from his unconventional childhood through two years in the Aleutians, where the army posted him as a cryptographer during the Second World War; New York from 1946; Paris in the fifties; Rome for the next twenty five years; and the anticlimactic denouement back home from 1979 until his untimely death from drinking in 1998.

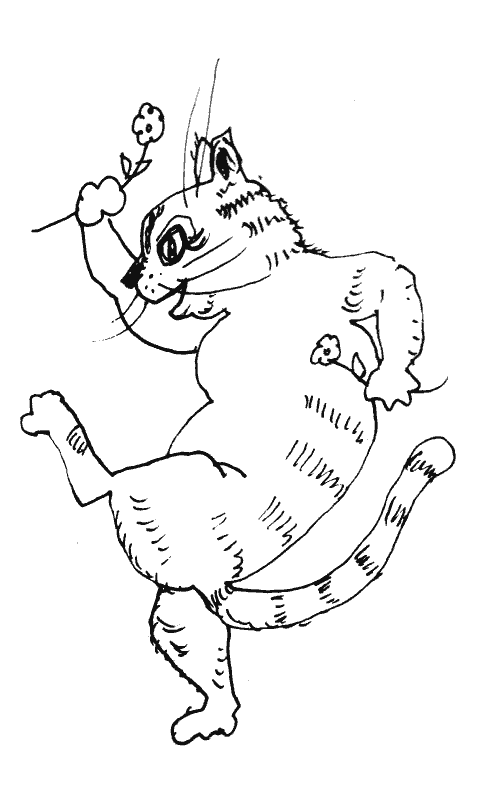

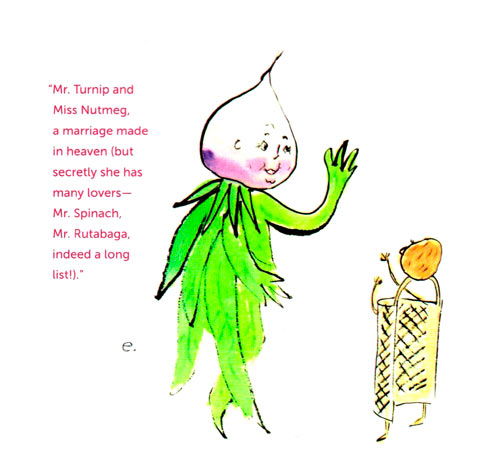

Along the way he somehow found time to write a novel and novellas, short stories, poetry, cookbooks and screenplays in between his many other vocations and avocations. To illustrate his writing as well as entertain his friends, Walter drew what he always called ‘squiggles,’ spindly depictions of anthropomorphic vegetables and various other foods, the cats and monkeys he cherished, the friends and his antagonists. From an early age Walter constructed puppets and staged elaborate performances with them. In any idiom Walter’s work lists discernibly southern.

This tolerant cosmopolitan remained a champion of the south all his life. “My nationality,” Walter wrote,

“is Southern before it is American…. The region called ‘the South’ has little real unity whether in terms of geography, historical development, linguistic or cultural tradition, yet people from the area are Southerners first and Georgians, Mississippians or whatever after that.” ( Southern Style 8)

Not, however, Texans or Louisianans, culturally distinctive in their own way, especially in terms of cuisine. Walter therefore excluded both states from his book on regional southern foodways. He might have omitted Florida as well; as the short chapter on that misbegotten state in his survey of southern cooking inadvertently indicates, Florida lacks much cultural identity at all.

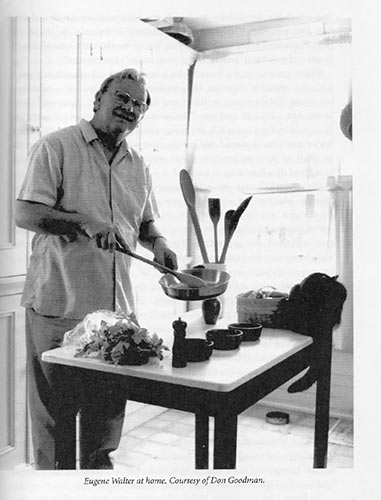

The man in one of his various milieu.

A distinctive southern identity, or more accurately Old Mobilian identity, is real enough when it comes to Walter himself. He fetishized the city as a magical place inhabited by nonconformists and suffused with sensuality. “All the fascinating contradictions of an immensely complicated region,” he explained in 1971, “manifest themselves there,” its history “a tangled skein.”

It enjoyed a microculture all its own, and Walter celebrated its

“spirit of slatternly arrogance and naivete, the raffish and sunny character of the town--the studied vif et gai .” ( Moments 233)

“Down in Mobile” the narrator begins Walter’s novel, The Untidy Pilgrim , “they’re all crazy, because the Gulf coast is the kingdom of monkeys, the land of clowns, ghosts and musicians, and Mobile is sweet lunacy’s county seat.” ( Pilgrim 11) Walter himself claimed to worship “the Three-Eyed Goddess of chaos, craziness and caprice.” ( Moon xvii)

He did not lack for self-regard, and instilled autobiographical elements into all the characters in the novel. One of them likes to repeat “tum-de-tum” during conversations (Walter used the phrase so often in Paris that George Plimpton referred to him by it); another refuses, pathologically, to suffer fools; an eccentric widow dotes on her cats and likes to read comics on the porch with the narrator, who loves monkeys. The widow relishes practical jokes and victimless transgression. An artist draws. There is an avid gardener and an epicure, while a girl on the Grand Tour in Paris whiles away hours with the assembled literati at the Café de Tournon.

2. A regionalist cosmopolitan.

No matter the location, he insists that he always lived as he “lived in Mobile” and told guests at his Rome apartment they had entered “extra-territorial Alabama.” ( Southern Style 131, 136, 10; Pilgrim 7) He kept a box of red Alabama dirt wherever he lived and grew southern staples in his terraced Roman garden between translating scripts (over five hundred of them), acting in numerous commercials and “about a hundred films,” several directed by Fellini (he played a mother superior who strips topless in one of them), others by Antonioni, Costa-Gavras, Lina Wertmuller and Franco Zeffirelli. His southern accent remained strong throughout his life. ( Moon 227, 233)

Walter was resourceful. An autodidact “without the brittle edge that often characterizes the learning of the self-taught,” ( Happy Table x) he never attended college but learned French to catch the raunchier Mobilian gossip, always conveyed in the language by old Mobilians to confound the kids; along with Plimpton and his “Harvard boys” founded The Paris Review , where he contributed fiction and reviewed art, dance, music and opera; and upon arrival in Rome quickly gained fluency in Italian. It was at one of his elaborate puppet presentations that Fellini found him irresistible. During the Rome years Walter also translated thousands of texts and “well over five hundred film scripts” from Italian. ( Moments 79; Moon 224)

It was to be the most productive period of his life. Walter had traveled to Rome at the request of an obscure Italian princesa from New London, Connecticut (she had married the money and seldom saw her philandering prince), to edit her multilingual literary journal, Botteghe Oscura . Among all those other things Walter did in Rome he gave Guiseppe di Lampedusa his first break by publishing a chapter from what would become The Leopard. Other editors had rejected it as ‘journalistic trash.’ Walter threw the publication party, where he introduced Lampedusa to Isak Dineson. They hit it off. ( Moon 202)

When Walter fell out with the princesa his principal source of income became ghosting the screenplays, many for a surprising market. It would be understatement to describe his approach as unorthodox. It enabled him to work fast.

“ ….South African film companies would send him novels from which he was to write bang-em-up film scripts. Eugene never read any of the novels. He read the titles, the jacket summary, and combed through the text for all the proper nouns. He made his plots up…. The film script writing business was lucrative, but he had never seen one of the resulting movies. His real name was to be found in none of the credits.” ( Moments 305)

Other than a few of the years in Rome he never had much money, which when he did have it he happily squandered, but Walter constantly entertained anyway. He threw lavish southern parties (“fun is worth any amount of preparation” was a favorite maxim), insisted on taking his daily southern nap and improvised southern dishes from the ingredients to hand. ( Moon 248)

“It was in the Aleutian Islands,” he said, “that I first began to cook.” On frigid Attu he dug for geoducks to cook with sauce creole and kept a clandestine dog he named Ragzina Gadzooks in the barracks. ( Moon 67, 68) Walter also recalls the aroma of gumbo simmering in the tiny Paris apartment where he had only a single alcohol burner. ( Moon 161, 160) Perhaps most impressive, he kept an ocean of Jim Beam at all times despite the colossal cost of spirits imported into France and Italy.

3. I am large, I contain multitudes, but I can be small and harbor horribilities.

Walter could be contradictory and incorrigible, one moment childlike and charming, the next childish and churlish. The darker side appears to have matured mostly in Mobile, although he also had rows and harbored resentments with a number of people in Rome. The notoriety and success of Gore Vidal for one galled Walter. ( Moments 302)

An academic acquainted with him admits that “Eugene could seem superficial and perhaps at times silly;” another refers to “awkward dinners at home and in restaurants” while a third admits “Eugene wasn’t always that much fun…. He could be demanding, obstinate, and irrational.” On a whim Walter could be vile to waiters or cooks. One of the more unpleasant stunts he enjoyed repeating arose from his hatred of pepper shakers, which he would hurl to the floor while berating staff for the absence of grinders. ( Moments 140, 156, 27, 227)

His behavior also betrays hints of a casual, perhaps not quite conscious racism. Walter complained to a contractor for sending “cheerful blacks” to repair the roof instead of appearing himself and attacked the New Orleans Symphony because one of its musicians wore a turban during the Iran hostage crisis. ( Moments 241, 277)

In Rome he had been fast friends with Leontyne Price until she abruptly severed contact. Stephen Zeitz, an acute observer of all things Walter, suspected why: “I had no doubt that he had gotten too close to her, that his innate sense of southern history… had reared its ugly head, and he had offended her with a careless comment.” ( Moments 302: ellipses in original)

Then again Walter did adore her and worked with Ralph Ellison in Paris, where he socialized with Vilma Howard, Lady Angela Lady, Richard Wright and William Gardner Smith, so it is hard to convict him of bigotry per se.

Much of the time Walter’s electrifying charisma and sporadically generous spirit salvaged his often fraught relationships.

4. Memoir by proxy.

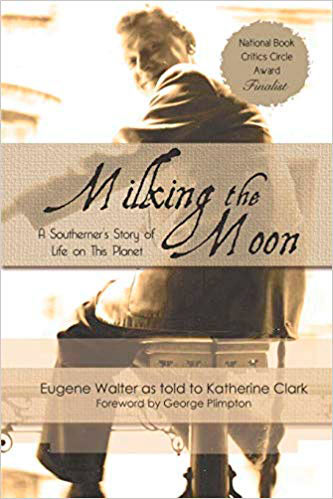

Notwithstanding his prolific output, Walter never got around to writing his memoir, an omission that should have immortalized him through the agency of Katherine Clark, a writer from New Orleans. She sat with him for interviews over a period of four months at the end of his life and captured his voice with uncanny immediacy. Milking the Moon is nothing like his writing style.

The voice is impish, discursive, expansive in the manner of the unbound salon; the writing taut, meticulous and ingratiating in the good sense.

Clark notes that acquaintances of Walter wondered whether he would tell her the truth and admits to her uncertainty about whether he did. She does not care. “I was not,” Clark explains, “after ‘the truth’ of Eugene’s life, whatever that was in terms of the facts. I wanted his stories.” Even his detractors endorsed them. Clark likens them to performance; “when it came to his favorite stories, he was like a great jazz improvisationist. There were familiar riffs and staples of his repertoire, and he never played them the same way twice.” ( Moon xix, xix-xx)

Clark has a point about the stories: They are good. The Depression deprives his grandparents of the beloved house where he lived with them after the loss of his parents at an early age. The grandparents fall ill and die; the local department store magnate, Hammond Gayfer, takes him into his magnificent house where visitors come and go. “Outside, he had jungle. He didn’t like lawns.”

Gayfer encouraged Walter to skip school and put on his puppet performances instead. “’School,’” Gayfer told him,

“‘is just something invented to keep children away so their parents can have some peace. If you want to find out anything, it’s all here.’ His house was papered with books.” [55]

One of the visitors

“was this very young man with bright red hair and greenish skin named Robert Penn Warren who was writing his first novel, Night Rider , in the back yard, in the Chinese pagoda, where the pheasants had lived until the cats ate them.” ( Moon 44)

Years later in Rome Walter and Ellison interviewed him for Botteghe Oscure.

After the interlude with Gayfer, who also died too young, Walter flees Mobile to avoid his placement by the state with “a nice Christian household,” a fate he understandably dreaded. [64] Walter joined the Civilian Conservation Corps at the age of seventeen, the only member of his group not on work release from reform school. He and the criminals made fast friends despite their disparate backgrounds, another testament to his tenacious charisma. They passed the time in part by singing three hundred ribald stanzas of “The Jolly Tinker” together; a few years later Walter “was able to sit down with Alan Lomax in Paris and thrill him with some stanzas of ‘The Jolly Tinker’ he had never heard.” [64-65]

Later, on leave from the army in New York, Walter encountered Tallulah Bankhead. When an ardent lover urged her to hurry home to bed, she instructed him to go and “get started without me.” Bankhead succumbed to Walter’s charm; she gave him some of her pubic hair.

Zev Daniel Harris, or ‘Zev’ alone as he styled himself, built Walter a reliquary for one of them and he kept it for the rest of his life along with the stuffed monkey he kept in a vitrine. According to Zev, who had a high reputation during his lifetime, “Walter was a walking civilization. He could do anything and knew everything.” Zev was not alone. According to another acquaintance, this one from the later Mobile days, Walter “was the most educated person I’d ever talked with for any length of time.”

The other strands of electric furr? Walter traded them for rare books. ( Moon 65; Moments 96-97, 107)

5. A night to remember.

During the fifties he met and disliked Anais Nin in New York. Lesser lights illuminated his life there which, however, he never much liked either.

A wealthy banker called Joseph with theater connections met Walter at one of his parties and befriended him. Joseph took Walter to dinner at a lavish restaurant with Nance O’Neil, by then a superannuated superstar of the stage, according to Walter some ninety five years of age when he met her. O’Neil was born “something like Phoebe Heberschloffen” in “a village of three hundred in Iowa” and a student of thespian history:

“Eliza O’Neil and Nance O’Field were those Restoration actresses who were among the first females to appear on the stage in Jacobean England. So she took Nance and O’Neil… because she felt she was a new movement of liberation for women in theater in America.” ( Moon 110)

The background Walter gave Clark is untrue with two exceptions. O’Neil was born Gertrude Lamson in Oakland, California during 1874, which puts her under eighty when she met Walter. A manager, not O’Neil, chose her succeeding stage names, first Beatrice and then Patrice before Nance but always O’Neil. The name Nance came from a Nance Oldfield but Walter is right about the derivation of O’Neil and both of his models were seventeenth century actors. (Carbone, Rouse)

She cut quite a figure. Preternaturally tall, O’Neil “had a voice she could bounce off the other end of Carnegie Hall without trying.” ( Moon 110) During the height of a prolific career O’Neil referred to herself as a “great beast of the stage.”

She traveled the world with an acting troupe during her twenties, to Europe, Hawaii, Australia, India then South Africa and lived outside Cairo following the tour. Married for a time at the age of forty-two, O’Neil lived with a series of beautiful young women for most of her life and may have slept with Lizzie Borden. (Carbone)

At the time O’Neil dined with Walter “she had dyed red hair which she obviously did herself because it was different shades in different patches…. seventeen shades of scarlet, orange and one patch of purple.” Clad in black lace, adorned with a “flashy diamond ring,” encumbered with “tons of pearls” and violently rouged, O’Neil “must have put on… mascara with a teaspoon…. And she had two wristwatches…. The very beautiful Cartier watch and the Felix the Cat watch.” ( Moon 111-12)

To the starstruck Walter she was “very slender, very elegant.”

Thanks to Joseph, O’Neil’s entrance to the restaurant was grand. He paid off the staff

“to do a sort of silent fanfare whenever she appeared at the door…. And the headwaiter was saying ‘Miss O’Neil, ah, Miss. O’Neil,’ while she just did her first act entrance…. There were bouquets at every table. They took away our little one on this table and brought a bigger one.”

O’Neil ordered “the usual” and Walter describes what ensued.

“Joseph ordered champagne, because when you entertain stars, you have champagne. She sipped a little, and they brought her a gallon of beer. What the usual was, was the biggest Welsh rabbit you ever saw in your life. A washbasin of Welsh rabbit. A pile of toast… over a foot high. She was smoking cigarettes two at a time…. All the time saying, ‘Oh, I was crazy about Oscar Wilde. He wasn’t a sissy at all.’ And I thought:

They don’t make them like they used to.” ( Moon 111-12)

It matters not whether O’Neil got a full gallon of beer or tower of toast. As stories go, Walter has taken a star turn.

6. The New Journalism.

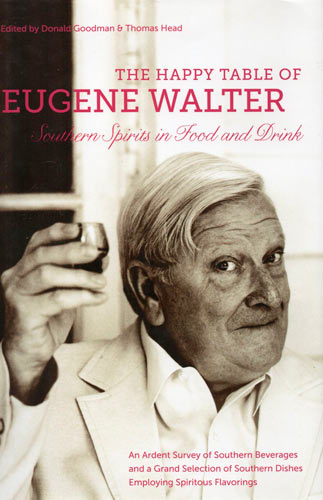

The habit of embroidering reality crept into work as well as conversation. The Happy Table of Eugene Walter , one of his southern cookbooks, is subtitled Southern Spirits in Food and Drink ; the cover further describes it as “An Ardent Survey of Southern Beverages and a Grand Selection of Southern Dishes Employing Spiritous Flavorings.” The preface also claims that all the recipes employ alcohol.

The first four recipes, however, include no booze and neither do many others. Some, like Brunswick Stew, add a gratuitous and unwelcome “splash” or spoonful of fortified wine to qualify. Walter does not mention the wine in his description of the traditional version from Southern Style and the recipe there omits it as well. A lot of dishes--gazpacho, a Caribbean chicken preparation, English potted foods--do not originate in the south. Bourbon is not “a highly popular pre-dinner drink in England.”

Measuring the ‘proof’ or alcoholic content of a liquor there did not result in “conflagration, even explosion, and the services of the fire department.” Nor might powder “smolder.” Instead,

“the original test involved soaking a pellet of gunpowder with the liquor. If it was still possible to ignite the wet gunpowder, the alcohol content of the liquor was rated above proof and it was taxed at a higher rate, and vice versa if the gunpowder failed to ignite.”

England had replaced the test, which, although Walter does not say so, was a tool of taxation based on alcohol strength, by the eighteenth century. ( Happy Table 19; Jensen 1258-59)

None of these deceptions is particularly troublesome and they do not detract from the appeal of The Happy Table but they do demonstrate Walters’ idiosyncratic, habitual conflation of fact and fiction.

After failing to obtain an interview with Fellini, Walter published a detailed fabrication, which the merrily subversive Fellini embraced to the point that he referred other hopeful reporters to the text. Walter also had a habit of ascribing imagined statements to people whom he actually had interviewed, to their immense irritation.

According to Ann Gavell, a journalist and acquaintance, Walter was a fact checker’s nightmare and legal liability but, to him, his maddening method served a purpose. “For Eugene,” she explains, “journalistic integrity required that the reader be amused.” He not only fabricated quotations but even retouched photographs of the people he interviewed; “no dull image was safe…. The inked in scepters, added tiaras, and pasted on ascots usually had the intended effect of making readers smile, if not puzzle a bit.” ( Moments 229, 274)

Walter himself considered the blurring of fact and fiction integral to his vision of southern culture. In Southern Style he also conflates his own personality with the character of the region; “the South,” he maintains,

“is quirky, quick to take offense, fanciful: it has an attitude, a frame of mind. It prefers the flowery to the plain, likes its own jokes, its own rhetoric. It can laugh at itself at home, but is immediately riled at any snicker from outside.” ( Southern Style 10)

7. Mobile and the symbiosis of sex.

Milking the Moon jumps to a saucy start with Walter’s description of Mobile during the 1920s . Its proliferation of brothels was, he insists at the outset, an unalloyed asset, and not only for the service of sailors on shore leave. His judgment sounds sane enough on the subject of sailors;

“instead of finding a town with no bordellos, nothing but bars where they would get drunk and fight and kill each other or kill whoever was passing, in Mobile they could have a good fuck and drink and be happy.”

Then his perspective becomes a bit more problematic for twenty-first century readers. There were the “mad country boys dying for a blow job. And their born-again Baptist wives wouldn’t give them one.” ( Moon 8)

The whores, he thinks, also provided relief for overworked Mobile wives and release for their husbands. It was not that the city was awash with loveless marriages. “Boys,” according to Walter, “have to get their rocks off every eight to twenty-four hours. It’s not my idea--Mother Nature made them that way…. beginning at 12 and going on to 112.” It was too much for women with “three or four children, two dogs, one servant, household to clean, laundry--they were so glad if the boys went and got it off before they came home at night.” ( Moon 7, 122)

Mobile remained a city connected not only to the sea but also to its hinterland. The whorehouses provided opportunity to uninhibited “country girls” otherwise stuck on the farm.

“And having seen dogs, cats, cows, horses, pheasants, and guinea hens copulating, there was no news to them about copulation. It was just something boys wanted to do. So they would come to town and work for three or four years in a bordello and save every penny. Go home and buy themselves a pocket handkerchief, find ‘em a guy and marry, and raise eight children. Pillars of the church. Modest downcast eyes. They never told all they knew.”

“So the bordellos,” Walter concludes, “kept everything in balance.” ( Moon 8)

8. No sex please, I’m inscrutable.

None of this should be taken to infer that Walter was lascivious in print. While he did not shy from the subject, sex does not much feature in his fiction. When it does, he treats the subject with a worldly reticence.

In two short passages from The Untidy Pilgrim , the not altogether likeable protagonist wonders of his beguiling and treacherous lover, ironically named Philene (’lover of humanity’): “Was there ever a girl who was a tract against clothes, like Philene?” The night before she jilts him, Philene

“pressed her whole body fiercely against me. The girl had turned tigress. I was amused at her, and thought it was part play-acting, and pretended to roughhouse with her. Then I saw her face, which was the naked face of desire, her dark eyes shining. Our love-making was of the wildest. It would be difficult to say whether it was love or a duel. Some challenge was involved, and certainly some curious anonymity.” ( Pilgrim 46, 113)

The scene itself is playacting on Walter’s part. Although he admired the “polysexuality” of his European acquaintances whom, he claims, all had sex with “girls, boys, camels, watermelons;” adopted a decidedly camp persona (everyone was ‘dahling’); and at one point in Milking the Moon lists himself among the ‘gay boys’ invited to a party for ‘atmosphere,’ he never allowed anyone to get altogether intimate. Roy Simmons, an authority on Steinbeck, considered Walter a “lonely figure” despite “all the public flamboyance and the occasional outrageousness.” ( Moon 127, 133)

Something “elusive” about him precluded close friendships: Walter “could be completely reticent about some aspects of everyday life (his romances, if any) and exuberantly expressive about others.” Toward the end of his life he uncharacteristically confided to an acquaintance that “he never had a lover.” ( Moon 149; Moments 90, 141, 140)

As to the bordellos, Walter may, without prurience, have described the mores of prewar Mobile, or anyway the mores he believed held sway then and there.

9. Asylum below the salt line.

Not for nothing does Walter refer repeatedly to Baptists and the church. Mobile lay square within the bible belt, not ordinarily known for its acceptance of sexual license or much of anything else. Walter attributes the temperament of tolerance in Mobile not so much to its anomalous Catholicism (he “loathed” the “potato famine Irish Jesuits” who he says infested the city) but to its location below “the salt line” where anyone can smell the Gulf. It is, he maintains,

“an invisible defining line between Sunday South and Saturday-night South. It means Mardi Gras and parties on this side, and it means Sunday school on the other…. When you get to the coast, you see, you’ve got pirates and drama and Carnival and fishing fleets and smuggling and so many different skies and thunderstorms, like this constantly changing pageant in the background. It’s another country.” ( Moon 33, 6)

“We are not,” Walter warns, “North America. We are North Haiti.” ( Moon 5) In this telling Mobile sounds like a microcosm of New Orleans, in literal terms too; the cities share a number of street names, among them Bienville, Conti, Dauphine. The similarities extend to the culture of food. To cite one example, Walter’s cousins operated a restaurant with “280-something dishes on the menu, and they were all cooked to order;” venison, hams, guinea hens. The place had a “a wonderful wine list” too, featuring bottles from around the world stocked with the connivance of a corrupt customs inspector. ( Moon 7)

The depiction by Walter of Mobilian mores probably is accurate. Writing in 1990 about the city during the 1870s a historian of southern Alabama, George Daniels, quotes the conclusion of Don Doyle that the city “responded to the challenges of the New South with drink and festivity.” An 1884 Harper’s Weekly article reports much the same thing. In Mobile, its author observes, “the whole people are amusement lovers and the Creole blood touches everything with lightness and beauty.” Mobilians of a certain stratum, Walter himself among them, remain proud that their city was the first in North America to celebrate Carnival. (Daniels xxiv; Doyle 247; DeLeon)

10. Mobilian foodways.

His grandparents imparted their passion for food to him. They kept a garden behind the house. His grandfather worked in the wholesale produce business, brewed his own beer and bottled his own wine. Prohibition posed no impediment, although especially when the priest came to dinner, bottles of the wine had a propensity to explode “in that mysterious dining-room closet where the Christmas fruitcakes aged in port or bourbon…. ” ( Southern Style 15, 19)

“Everything in my early life,” Walter recounts, “was concerned with fine foods and wines, with gardening. I was in a kitchen and at a table forever.” ( Moon 15) His household was typical of Mobile in the 1920s and 30s. “One thought food, talked food; the quest for the freshest and the best never ended.” ( Southern Style 19)

At home with his grandparents Walter recalls all kinds of vegetables and fruit, countless pork products, gumbo, little steaks wrapped in bacon, biscuits, pies, pickled peaches; and crab, crawfish, oysters, shrimp, snapper, all fresh off the Mobile docks, along with lots more. Again Prohibition posed little problem. Everyone, it seems, brewed beer and made wine; imports of alcohol proceeded apace, if with some precautions. Reminiscing with Clark, Walter remembers

“moments, when I was a little brat, about 1926, when a company… down on the waterfront of Mobile used to ship Champagne, each bottle insulated in a Sunday section of the Mobile Register , to old families in the driest sections of Alabama, [33] ‘dry’ even before Prohibition, ‘dry’ even as I sit here now…. When I asked what those bottles, being carefully packed into Heinz soup and Miss Louc canned vegetable cartons, contained, Mr. S., the shipper… gave a smile, which was a masterpiece of our (French) southern hypocrisy, ruffled my hair, and said, ‘Medicine.’ He was correct, of course.” ( Happy Table 32-33)

The anecdote is important because for a certain segment of southern society Champagne was as embedded in the cultural fabric as it remains in Britain, the world’s biggest consumer of the celebratory sparkler.

“Any book on southern drinking habits must, if it is not to be ridiculed by old families in those so-called dry counties, occupy itself, if only in passing, with the theme of Champagne. That sparkling wine in symbolic, bosomy bottles from that section of France is the very symbol of happiness, gaiety, erotic games and pleasure, poetry, art, and the best of Europe imported into the new world, nostalgia, healthful cooking, the afternoon nap, unflappable tempers, and civilization.” ( Happy Table 32)

11. Porch as boudoir.

The exuberant Walter household lived what he called the life of the porch and he lamented its passing with the onset of air conditioning. “Midmorning in that house on the corner of Bayou and Conti Street,” he recalled, “was a kind of mad levee, a morning party like those held by Louis XIV of France when people were received and the day’s events were discussed.”

The people his grandmother Ma-Ma received were no nobles of sword, robe or chancery, no wearers of ribands blue, white or red. Instead, they were people of all colors who shared a connection to the kitchen and a certain idiosyncrasy. First in; a ghostly presence, the silent boboshilly, a “seemingly weightless” native American woman who “wore a cotton print dress faded almost to white, and a kind of turban of white cloth.” She would sell file, burnet, bay and, after a frost, persimmons.

Then Miz Mimms, “the country butter lady” would arrive in her decomposing car. She was a “pure Anglo-Saxon provincial type” whose style was “tacky.” “In really hot weather Miz Mimms wore a large cabbage leaf on her head, and said it was the only thing that kept off the heat of the sun.” She kept her butter in the rumble seat.

Drivers of vegetable wagons--runner beans, crowder peas, okra, squash--and the iceman, knife man, itinerant tinker, “poor widow who made wax flowers” not to mention “lightwood man who sold pine knots for the stove and fireplace” each arrived on regular rotation. The “soft-spoken and gentle” gardener appeared as well. Walter saw his bearded Old Testament face “in practically all of Coptic Art.” They, Ma-Ma’s black cook and the neighbors all got their glasses of iced tea on the porch with a side of gossip. Best was the oysterman

“with his pushcart full of ice and oysters covered by a great burlap that smelled part wet dog and part rowboat, an umbrella on a pole quaking over all. His cry carried for blocks: ‘Oy-ay-ees-oyster man, manny-man, manny-man, manny-man!’” ( Southern Style 13-14, 16)

Ma-Ma was herself a formidable figure, a monarch who held sway not only over the mad levee but also over her kitchen despite the cook, who sounds as much like a congenial companion as a servant. Walter learned a lot from his grandmother; food lessons, life lessons and lessons intertwining food and life. One involved how to select a melon. “The various melons,” Walter claims, “were always a great delicacy in Turkey. To eat or to hump.” Apparently they served the same dual purpose in Mobile. His

“grandmother used to say that when you buy a melon in the market, if it has a triangular hole cut in it, then its all right. They’ve plugged it to see if its ripe. If it has a round hole in it, don’t buy it.” ( Moon 122)

A virginal watermelon.

12. Biographical fact and fiction.

All the vocational training in Mobile served Walter well when he turned to writing cookbooks, although it would not have pleased Time-Life books to discover the methodology he employed to write American Cooking: Southern Style , a volume in the publisher’s otherwise factual series about cuisines of the world based in large measure on interviews with notable chefs and accomplished home cooks.

According to Gavell, a journalist and acquaintance, Walter “used a composite of the people he met and knew to form the characters in this cookbook…. Many thought it was the best novel he ever wrote.” Walter himself encouraged the conceit. As “his longtime patron and dear friend” Nell Burks told John T. Edge: “Eugene was proud of that book. He told me that it was his best work of fiction.” Gavell’s mother for instance became a ‘Miss Charlotte Winn’ who spouts southern sayings and spends her time baking cornbread and cakes in a cast iron skillet. ( Moments 257; Cornbread Nation 22; Southern Style 132-33)

Walter’s enthusiasm for the kitchen, however, was genuine enough. It also was unpretentious. Notwithstanding his cookbooks and a formidable reputation among his dinner guests until the later melancholy Mobile years, Walter dismissed the acclaim. “I’m not a chef,” he insisted:

“I’m an experimental scullery boy. I like to eat. I’m a greedy guts, and any greedy guts becomes a good cook after exposure to simple utensils, a knowledge of heated coals, and a knowledge of seasonings.” ( Milking 249)

Walter did admit in Milking the Moon that particularly during his two decades in Rome he liked “to make people dishes they never tasted before.” ( Moon 248) Those dishes might include southern food for European dinner guests and European food for Americans visiting Rome.

13. An imagined south.

It turns out that Walter is a reliable enough narrator when it comes to some foodways at least some of the time, if not when it comes to the people who practiced them. American Cooking: Southern Style was his first cookbook. He got the commission following a chance encounter in Rome with a Time-Life editor during 1971. The publisher flew him to and from the city for the assignment and, because Walter never learned to drive, hired him a driver, “Mario Dubsky, a young Czechoslovakian painter of only slight acquaintance” for what turned out to be a five thousand mile vault across the south. ( Cornbread Nation 21)

For reasons unknown, “Walter was to complete his research and writing in two months” even though “most Time-Life authors worked on a two-year cycle.” The accelerated research timetable was of course possible because Walter fabricated so much of the book. Sources aside, Edge believes Walter knew what he was doing. Edge, a revered authority on southern foodways, considers the text, which Walter drafted after returning to Rome, “nothing short of revelatory.” ( Cornbread Nation 21, 22)

As Edge explains quoting from Southern Style , Walter celebrates an entire culture, and given the date of publication a remarkably inclusive one:

“[E]ven among the tugs and hesitancies of Southern history there is reason to rejoice that all Southerners of whatever pigmentation or persuasion have retained an appreciation of the table as something more than just the place where one eats…. The immediate impact of Southern cookery… is one of great pleasure, but by implication its message is even more profound.” ( quoted at Cornbread Nation 22)

His appraisal may be accurate, but the confounding Walter never conveys the precise message in play.

Furthermore it remains unclear what Walter was revealing other than his own imagined world. After all, he did revel in retailing the tale that Southern Style is fictive. That more than likely is the case. Walter, for example, includes a fulsome chapter on “The South’s Great Gift of Soul Food” in which he extolls the idiom.

‘Soul’ itself, according to Walter, “is a basic element of… a black life-style that disdains the hide-bound Anglo-Saxon culture and instead emphasizes directness, spontaneity and uninhibited feeling.” Whether or not anyone would agree with him, Walter himself could not have contemplated any higher form of praise than that definition.

“The food,” he maintains,

“originated as the food of the black South, or, more accurately, as food of the poor South; and after the South’s defeat in the Civil War it became everybody’s food.”

Soul food, he adds,

“is an Afro-American invention…. It was not brought over from Africa. What the Africans contributed was their ingenuity. Torn from their native land and thrust into the strange new environment of the Southern plantation, they were forced to make do, and they responded with remarkable resourcefulness.” ( Southern Style 109)

Recent scholarship has undercut the notion that Africans contributed only ingenuity to the cuisine of the south: Slaves likely brought with them a number of techniques and foodstuffs, including among other things sesame and okra, but Walter’s admiration sounds genuine enough. “Pork, greens, or whatever, soul food comes close to being a religion among its devotees.” ( Southern Style 111) Lest anyone harbor any notion to the contrary, Walter is unequivocal in calling soul food “a highly distinctive cuisine.” ( Southern Style 110)

That was in 1971. Exactly four decades later, Walter was equally unequivocal. “Nothing irritates me more,” he rants in The Happy Table , “than the phrase ‘soul food,’ a catchall label for the simpler and more traditional southern dishes.” During the 1950s or 60s, he maintains,

“some smart aleck or other, with imprecise reasoning, decided to split southern cooking into rural, po’ folks, mostly black cooking and fancy, citified, mostly white cooking. All wrong! There are as many social classes and degrees of culinary sophistication among blacks as among whites in the Deep South…. ” ( Happy Table 4)

Perhaps Walter’s view evolved. It is difficult, however, to reconcile these assessments, and the second emotive one sounds more like Walter than the oracular pronouncement he gave to Time-Life .

Walter also includes a lengthy and (slightly) less flamboyant description of life with his grandparents in Southern Style than the description he gave Clark, passing off what he later would label the ‘mad levee’ as a lifestyle typical to the deep south which, although amusing, obviously is not. In both The Untidy Pilgrim , which appeared almost two decades before Southern Style , and Milking the Moon he makes a case for the exceptionalism of Mobile. His editors at Time-Life appear not to have noticed.

They, and Walter, stand on a firmer factual footing when it comes to the food itself. Or not quite; in fact Walter wrote only the text of Southern Style , as the finest of print on its copyright page notes. Michael Field, a prominent cookbook author of the time, provided the recipes with the assistance of several Time-Life staffers .

14. Southern foodways.

Walter does get a number of things right about southern cooking throughout Southern Style. In Virginia he found distinctively southern dishes--spoonbread and cornpone, that Brunswick stew--but also a pervasive English influence on the historical foodways of the state, citing the 1746 account of an English visitor:

“All over the colony… full Tables… speak something like the old Roast-beef Ages of our Forefathers… Their Breakfast Tables have… Coffee, Tea, Chocolate, Venison-pasty, Punch, and Beer, or Cyder… their Dinner good Beef, Veal, Mutton, Venison, Turkies and Geese, wild and tame, Fowls… Pies, Puddings…. ”

“The English influence,” Walter believed in 1971, “is still much in evidence at the more elegant tables of Tidewater Virginia.” At the time he found roast beef and lamb, “Sally Lunn, made with yeast, from an English recipe,” wine jelly set in custard and during the holidays “rich dark fruitcakes and plum puddings with brandy sauce.” ( Southern Style 69; ellipses in original)

Walter does not say so, but the recipe for shrimp paste represents an unmistakable version of English potted shrimp set in butter and seasoned with its characteristic cayenne, mace, mustard and Sherry. ( Southern Style 103)

Walter also discusses a method for baking ham straight from the kitchens of eighteenth century England. The technique, now unknown to most Americans, is identical to the one Elisabeth Ayrton describes in The Cookery of England , although unlike her Walter flavors the ham with some quintessentially English ingredients; cayenne and, here again, Sherry.

“The traditional recipe calls for baking the ham in a blanket of stiff flour-and-water paste. After you bake it for six hours in a moderate oven, you remove the paste, sprinkle the ham with a few fine crumbs and return it to the oven for half an hour, dusting it with cayenne and basting it every five minutes with one cup of light dry red wine and two tablespoons of sherry.” ( Southern Style 55-56; compare Ayrton 80)

Walter or a staffer dug deep indeed to discover ham stuffed with greens. As Kim Severson wrote last year, “it is one of America’s most regionally specific dishes, but has never migrated beyond its home” in St. Mary’s County. According to her, unless you have been there, “you’ve probably never heard of stuffed ham.” (Severson) Walter, however, also found ham “stuffed with fresh greens” in Charles County. ( Southern Style 55)

Walter says little about the dish but does acknowledge that it is among “some rather special preferences” he encounters. ( Southern Style 32) Severson’s version stuffs the ham with a lot of cabbage, a little kale and sometimes celery robustly seasoned with black pepper and red pepper flakes. The recipe in Southern Style seasons the stuffing the same way but calls for celery, mustard greens, scallions and spinach.

“The ham,” according to Severson, “has a very distant cousin called stuffed chine” from Lincolnshire but cites Joyce White and unnamed “other regional historians” to claim its “Afro-Caribbean roots.” None of them provides any evidence for that derivation, however, and on closer inspection Lincolnshire chine does not appear so distant a cousin.

Both preparations start with cured pork and both look the same, with alternating bands of pink and green; both of them are served cold. The Lincolnshire method does stuff a cured shoulder that includes the spine rather than a ham, while in contrast White speculates that “indentured or enslaved West Africans may have stuffed uncured “jowls or whatever chunks of pork they had on hand” with unspecified “greens and onions left over from the winter garden.”

“Parsley” according to “Slow Food in the UK,” “is now the only, or dominant, stuffing ingredient” for the chine but “in the past a wide variety of herbs were [sic] used such as lettuce leaves, young nettles, thyme, marjoram, sage and blackcurrant leaves.” (“Slow Food”) The great Jane Grigson recommends stuffing a chine with “an enormous chopping of parsley, and other greenery if you like,” which hardly excludes cabbage or kale, both ubiquitous features of seventeenth century British gardens. (Grigson)

Severson probably is right that the Maryland stuffed ham is “an amalgam of a dish” that blurs “the line between black and white food” but its antecedents look unmistakably English. Walter infers that the Maryland version arises from “the tradition of good eating founded by the colonists” while the Times tends to discount the British influence on foodways in America more generally. ( Southern Style 32) This is likely one of the things Walter got right.

Incidentally a chine probably is the better bet if you can get one. The stuffing for both the Lincolnshire original and Maryland variant described in Southern Style fills a series of slits cut into the meat. As Mrs. Grigson notes of using the chine, when “you make a deep slash from fat to bone [y]ou will not go through, as there is the unseen barrier of the vertebrae wings of bone.” (Grigson)

15. ‘Southern’ foodways.

Walter finished Delectable Dishes from Termite Hall in 1982. The title refers to an actual inn outside Mobile, locally famous for its hospitality and also because one of the proprietors had fallen through a floor due to the bug in the title of the book. Walter spent a lot of time there, sponging as usual and spinning his tales to the delight of staff and guests alike. As with most of his creations, the label he chose for the book is not quite right. The range of sources runs a long way past its name, as the typically whimsical, baroque subtitle he chose for this putatively southern cookbook indicates:

“ Rare and Unusual Recipes from Old Mobile, France, Holland, Spring Hill, Italy, Denmark, Bayou la Batre, Dog River, Germany, Spain, Natchez, Coden & Divers Other Pleasant Locations. ”

The conceit in play pretends that Termite Hall used, or perhaps might or could have used, all the recipes. That notion allows Walter a broad enough definition of southern food to claim any dish he likes for his beloved region. Unlike Southern Style , Termite Hall includes little text other than the recipes, although many of them include clever confiding commentary and the final chapter, “Author’s admonitions,” is a solid enough guide to avoiding bad ingredients. The writing throughout is spry, the recipes clear and concise.

The frontispiece to Termite Hall indicates that it is “[i]llustrated with old cuts from the archives of THE WILLOUGHBY INSTITUTE.” The institute and its affiliated Willoughby Foundation are figments of a Dr. Willoughby’s imagination. The doctor in turn is a figment of Walter’s, who used the alter ego and its entities by turns for misdirection, mischief, mayhem and whimsy, although the ‘foundation’ did actually and eagerly accept ‘donations’ to help keep its ‘creator’ afloat.

Detailed as it is, the subtitle of Termite Hall omits a significant Other Pleasant Locality. Although Walter claimed to dislike anything English--“they had betrayed us in the war”--in fact “he was a sucker for the high-toned accents” of young English women he constantly hired and fired as his secretary in Rome. All of them were unreliable because, according to a contemporary, “[t]heir longevity… was determined by the quality and quantity of sex” with the local lookers they managed to seduce. ( Moments 301, 305)

Walter includes a few recipes from the British Isles in Termite Hall , and later would provide a raft of them in The Happy Table , but then one of his considerable strengths is the fact that he never allowed consistency or logic to interfere with the fun. As he told Pat Conroy, an acquaintance and admirer whose oral history Clark also recorded, as a cookbook author he needed to disguise the reality that his “real job is to be a philosopher king and prince of elves.” ( Termite Hall n.p.)

Walter mounts the robust defense of English food that Orwell failed to provide the British Council some three decades earlier. The Walter polemic, presented in the context of a recipe for steak and kidney pie that includes an appendix of four ‘ arpeggios ’ was provocative in its time. The pie is, he insists, “one of the greatest of all dishes for a chilly evening. It is one of the classics of British cookery and only one of the reasons to regret the bad name British food has had in recent decades” that has

“pushed so many great British dishes into semi-obscurity. But oh my if. In those islands, you hit upon the right country pub or eatery, the right hotel or tavern, the variety of fabulous dishes is only slightly less than those of France or Italy, the paradises of the greedy-gut.”

Walter being Walter, however, he cannot resist going on to traffic in truthiness:

“Louis XVI drank English cider with his meals, he employed only British cooks to prepare his meats and they were given passes to cross frontiers even in wartime.” ( Termite Hall 120)

The Happy Table cites the “stalwart Mrs. Beeton” and Elizabeth Raffald, who is quoted in connection with a recipe for oyster loaf, a London original predating the North American plantation but frequently appropriated by chauvinists of southern cooking. His recognition of Mrs. Raffald is impressive; back in 1982 few American writers were aware of her exemplary 1769 cookbook.

Altogether The Happy Table includes over two dozen recognizably British dishes along with quite a few drinks. Some of the food and drink is identified as such, some of it misattributed to other cultures. Others including Black Velvet are not attributed to any source at all. Walter likes sippets, an ancient English version of fried bread, with his southern greens.

Among other entries in the book, Madeira sauce for one has been a British standby for centuries; Walter describes it only in the context of French food. He has recipes for both celery and rhubarb sauce but gives neither one a source. Although his versions are predictably eccentric--yogurt instead of cream or milk for the celery, a misguided addition of tomato sauce to the rhubarb--their derivation is unquestionably British.

Walter claims celery sauce as a ‘forgotten garnish’ for seafood but in fact it historically pairs with boiled birds of many species. He does claim rhubarb sauce for fish but cuts it into small pieces to simmer instead of saucing filets whether baked, grilled or poached in the traditional manner. The radish sauce Walter also describes as a forgotten seafood garnish is new to us, a welcome addition to the repertoire of any cook to serve with steak as well as fish. Skip the pickles Walter adds to the sauce; they overwhelm the radish.

Walter’s “cheese spread” is potted cheese in disguise; “Chicken Custard” is but a pseudonym for British batter pudding. While in the past what now is called toad in the hole might have included chicken, other birds and any game or meat, it now has become more narrowly associated with sausage. Good of Walter to harken back even if he fails to provide the pedigree of the pudding.

“Italian pork chops” cooked with apples, beer and cabbage might come out of a British or central European kitchen but not from anyplace on the boot. His “Braised Duck” takes mace, its only spice, from the British larder.

Otherwise Walter offers his reader recipes for “Mushrooms, English Style;” a mushroom pie; Yorkshire Potatoes; spiced oranges; the eighteenth century oyster loaf from Mrs. Raffald; a number of “relishes” that are chutnoid; shanks in stout; curried shrimp; a baker’s dozen punches; white fruit cake like the ones Ma-Ma aged in the closet; mince pie made with the traditional tongue; “English Summer Pudding;” Tipsy Cake and Tipsy Parson.

“The British Isles,” Walter admits, “make up the Magical Kingdom of Puddings. They have literally hundreds.” Summer pudding, he explains, “is positively feebleminded, it’s so simple. But oh, is it good!” ( Happy Table 182) He is right on both counts.

On tipsy cake; There exist “so many different family recipes that it would take the Good Housekeeping Institute a half-century to try them all.” It is the southern adaptation of British “‘pre Victoria’” trifle recipes. Walter describes three versions, all of them good. ( Happy Table 192) We will genuflect to Walter by giving the south credit for them.

Then there is Walter’s “Goober Toast” that he also describes for Clark in Milking the Moon. Not British, does not sound promising, in fact it sounds vile, but Walter has practiced some kind of southern alchemy with this one; toast or an English muffin layered with butter, mustard, “good American peanut butter” baked until the last layer “looks like it wants to splutter” then topped with cold kosher dills. ( Happy Table 57) We use cornichon.

Goober Toast material.

16. Stuck inside of Mobile….

By 1979, when Walter’s funding had evaporated and he had begun to fear the political violence fomented by the Red Brigades, he left Rome to return to Mobile. “It wasn’t,” according to Tommy Weir, a documentary filmmaker, “as big a homecoming as he would have hoped.”

“After an absence of more than thirty years,” Edge explains,

“few people knew what to make of the fifty-seven-year-old eccentric. Walter was a cipher, a songbird-voiced dandy with a labyrinthine intellect, able to hold forth with equal gusto on the failings of Zeno and the charms of Dolly Parton. But la dolce vita was over.” ( Cornbread Nation 22-23)

“In Rome,” adds Zeitz, an acquaintance there and then in Mobile,

“Eugene had been a relatively important person in a colossally important town. In Mobile he became a caricature of himself. He grotesquely aped the boy he remembered being and the artist he had invented.” ( Moments 307)

His assessment does not sound unduly harsh. Despite a heroic effort by Rebecca Barrett and Carolyn Haines to collect encomia to Walter, a depressing portrait of his tenure in Mobile emerges from their collection, Moments with Eugene . In great measure Walter sang for his supper by retelling tales of the glory years.

When in Rome, hang out with Fellini and appear in Italian films.

He recounted his encounters not only with Warren and Bankhead, Nin and Dinesen, Fellini and Lampedusa, but also with Truman Capote, T. S. Eliot, Judy Garland, Greta Garbo, Archibald MacNeice (not a favorite), Price, Muriel Spark (Walter would name a chicken recipe for her but missed the chance to conjure a rabbit O’Neil), Dylan Thomas, Alice B. Toklas, Vidal; anyone of cultural stature sought out the Walter Salon upon arrival in Rome. The notion, not entirely facetious, circulated that the only other indispensable audience in the city was the pontiff.

In Walter’s hands, or rather through his voice, the stories were not so much namedropping as what Jonathan Yardley calls “the higher gossip.” Walter could suspend disbelief to enchant each companion and convince each in turn that she was his most treasured acquaintance, so special that she alone was treated to secret stories. Each in turn could become a “benefactor” uniquely suited to sustain Walter both spiritually, spiritously and otherwise materially.

Most of his acquaintances eventually would realize that Walter serially recycled the captivating tales he told but the deception seldom stung. A reporter affiliated with Mobile public television thought he had scooped all rivals after interviewing Walter:

“The stories seemed spontaneous and fresh, sometimes as if my questions had reminded him of matters or anecdotes he hadn’t called to mind in years. Later… others would tell me these stories were Eugene’s stock in trade; he had been regaling Mobile parties with these anecdotes for a decade. But they were newly minted as far as I was concerned. The temptation was to feel fooled: I felt special; Eugene was acting. There really was no contradiction.” ( Moments 157)

Selective deception also sustained Walter during the Mobile years. The same reporter explains that taking Eugene to dinner--and it always was Eugene, never Walter or Mr. Walter, in conversation, on the air or in print--made him feel special. Driving Walter

“as we did, we had no idea what Eugene’s day-to-day life was like. I can tell you though that the impression one got was that it was a desert for him between visits, that no one else took him to dinner or anywhere else. Only after his death did it become somewhat clear to me what a large, complex network of friends and supporters Eugene had in Mobile, to drive him to the post office, the grocery store, doctors’ appointments, to take him to lunch, and so on.” ( Moments 156)

By the time he returned to Mobile, it would be reasonable to conclude that Walter was diminished if not defeated. Reasonable, but perhaps not entirely accurate; while he alienated a lot of acquaintances over time, as he admits more of them women than men, Walter managed to retain a retinue of adoring acolytes even if his celebrity appears to have been confined to the city and its immediate environs. Nearly all the testimonials from Moments with Eugene originate with Mobile or its south Alabama hinterland.

In part Mobilians loved him because he was a beacon in bleak times. At the time Walter arrived from Rome Mobile had reached nadir. A preservationist explains how the economy of the city had tanked after flight to the suburbs gutted its tax base “and then the city government and downtown property owners had administered the coup de grace by tearing down hundreds, indeed, thousands of nineteenth century houses and buildings.” Walter himself described his cherished city as resembling “a North African city after bombardment, with gaping spaces.” ( Moments 232, 233)

His shambolic ‘business model’ was based on the sort of Renaissance patronage system he had enjoyed for a while with the princesa in Rome, but not enough Medicis lived in Mobile to freeload at scale. He did get enough help to subsist from local patrons of the arts, academics, worthies and hangers-on eager to enhance their stature by association with a local legend. As a result Walter never needed to pick up the restaurant tab and never did.

Notwithstanding his putative devotion to ‘chaos, craziness and caprice,’ Walter drifted into a sordid, eventually unemployed routine. “I stay home much of the time,” he explained to the press,

“unless of course, someone’s buying dinner, and then I’m a boy with bells on. Otherwise, I simply rise and do a little sonnet writing, then take a nap, then read a little, eat a little, and then when there’s an emergency (and there always is), I fill my bathtub with Jim Beam and swim to safety.” ( quoted at Cornbread Nation 23)

His reference to immersion in a tub of Bourbon is an exaggeration but not by much. At that point Walter was drinking Port in the morning, Bourbon before lunch followed by cheap jug wine and the occasional Heineken with the food followed by more Port, more Bourbon before dinner, then more wine and “day-glow liqueurs” that “sported a wide variety of Mannerist hues and tints.” Walter “loved serving them for their colors, not their tastes which ran from bad to foul.” His chosen glassware consisted of dried beef jars. ( Moments 300, 215)

Dinners might be incongruous, even nauseating. All that chipped beef for instance had to pall and even in Rome Walter insisted on cooking stone ground grits with sliced Velveeta imported at eyewatering expense.

On one occasion back in Mobile he served a number of dinner guests a turkey carcass soup. Walter had foraged its principal ingredient from the neighbor’s garbage can. A favorite presentation was his “patent leather pie,” a ghastly tuna casserole covered in eggplant peelings.

Frank Imbragulio, a regional musician, literary commentator and self-described friend of Walter, never looked forward to dinner at his house. “There were,” Imbragulio explains, “just so many things he could do with Vienna sausage and other scrap meat bargains” and dining always “was delayed for hours… while Eugene slowly sipped glass after glass of red wine, always at room temperature” in the Alabama heat. ( Moments 307, 38, 41-42)

Not the Vienna one might have hoped for.

Another acquaintance of Walter’s in the Mobile years, one of several close enough to drive him on errands or out to lunch, however, recalls him serving “coquilles with crab and perch, ham in aspic, and cabbage and carrots soaked in ginger.” Some diners actually enjoyed their patent leather. ( Moments 223, 38)

17. A la Palazzo dei Gatti.

Home was tantamount to a squalid squat. An elderly matron of the arts had purchased it for Walter and arranged through her bank to charge him a modest rent of $250. He never paid a penny. When the bank advised the matron that Walter should at least cover the maintenance costs of the house, he replied with venomous quasifactual letters blaming its disrepair on the bank. Walter had neglected the roof to the point that water poured through multiple leaks, the pipes froze and the place flooded to threaten his books, papers and ‘valuable’ piles of debris with destruction. The bank backed down and the matron continued to bankroll Walter.( Moments 240, 241-42)

His cats--Walter kept as many as seventeen of them--walked across, ate from and vomited furballs onto the plates of dinner guests. One of them refused to descend from a makeshift lattice of planks in the kitchen thrown across cabinet tops, door jambs and the refrigerator, a rickety edifice that complicated any attempt to cook.

Except for the “Cat-Free Room”--essentially a library where he kept the reliquary and vitrine along with mismatched display cases filled with ephemera and found objects (junk)--the cats used the house with indiscriminate indifference as a toilet. The apartment in Rome had been nearly as bad. One guest recalls that he “nearly choked when the smell of cat piss welcomed me.” Imbragulio hated the stench in Mobile and found himself exasperated by the way the cats destroyed the furniture. ( Moments 74, 42)

One of many Walter “squiggles” featuring cats.

18. A prolific imagination.

During the Mobile years Walter touted a number of book projects “slated for imminent release;” The Blockade Runners , a novel; The Baroque South , a sort of travelogue; an untitled history of Mobile “thick enough,” according to Walter, “to hold a door open in high wind;” Six Libretti in Search of a Composer ; and a number of culinary publications including The Dainty Glutton’s Handbook , Dixie Sips and Dixie Sups , The Eggplant: What It Is and Why We Like It , The Ginger Friend’s Cookbook , Grand Fugue on the Art of the Gumbo (scheduled, in 1982, to be “published in time for Christmas, 1983”), Root-a Toot-Toot: Rutabagas and Turnips , and We’re Quite Reasonable. Termite Hall and the Grand Fugue were to be the first installments of a ten volume opus, Table Talk. ( Cornbread Nation 23; Moments 232, 40; Termite Hall n.p.)

It was mostly, in the eloquent language of our august president, ‘bullshit.’ None of the projects other than Termite Hall made it into print, although Walter did narrate a short film clip that is a sort of condensed Grand Fugue under the same title. Walter also promised to write a number of scripts for collaborators that never reached the page. As one documentary filmmaker recounts, Walter

“lived in the present. He had no feelings for deadlines…. Once, when he promised to bring me a long-overdue script, he infuriated me by arriving instead with an eggplant.” ( Moments 20)

As Edge admits with uncharacteristic, and charitable, understatement, “in his final years, Walter was unfocused.”

It was not, however, that he did nothing. Along with Termite Hall ( The Happy Table appeared posthumously in a form heavily edited by Walter’s literary executors) he did publish an uneven work that has its points, the slight Hints and Pinches: A Concise Compendium of Herbs, Spices, and Aromatics with Illustrative Recipes and Asides on Relishes, Chutneys, and Other Such Concerns from 1991, “blazoned with Walter’s fanciful pen-and-ink drawings of mango-eating monkeys, dancing cats, and crown-bedecked bulbs of garlic.” It is, according to Edge “a funhouse encyclopedia, at turns scholarly and irreverent.” ( Cornbread Nation 23)

For a time Walter hosted a Saturday morning show on the local National Public Radio station and wrote for the Mobile Azalea City News and Review , a now defunct alternative weekly. The radio program, “Eugene at Large,” featured recipes, book reviews and Walter’s “idylls of Southern life, past and present.” ( Moments 173)

Not everything was idyllic about the process of broadcasting the radio show. “Endearing and infuriating” recalls the program director; “Eugene Walter could be both.” The director also recalls a number of “public humiliations… suffered thanks to Eugene.” ( Moments 90, 91)

And although as noted “the ACNR received heated complaints from several individuals about things they were reported to have said” during interviews, his columns, Table Talk and Eugene Walter Every Week , were generally well received and at times prescient. ( Moments 229)

A young staff writer at the ACNR during Walter’s tenure recalls that Table Talk

“projected a vision of European cuisine and vast cultural knowledge combined with southern home cooking. He seemed to have files of thousands of recipes…. He championed the idea of using traditional, local fresh fruits and vegetables.” ( Moments 227)

Sometimes Walter discussed recipes from nineteenth century Mobile restaurants. ( Moments 227) Nobody knew where he got them and at this remove it is an open question whether their source was his imagination.

In his capacity as arts reporter, Walter received free passes to “most theatrical events and all movies” in and around Mobile, which helped him sustain his stature as the city’s leading tastemaker and raconteur.

He also served as the weekly’s restaurant critic, a post that brought him a lot of fawning attention and bought a lot of free food because he announced his visits in advance. If the practice was hardly principled it was not uncommon at the time--the latterly controversial Tom Fitzmorris in New Orleans comes to mind--and the subjects of his ‘scrutiny’ benefited at least as much as Walter himself because he seldom wrote a negative review.

The casual corruption was not merely venal. It dovetailed with the newfound provincialism Walter adopted upon his return to Mobile. No longer the discoverer of epochal talent and auteur of Cinecitta, he became an unapologetic booster. “All performances, books, and expositions” recalls Gavell,

“were worthy of praise by virtue of the attempt at artistic expression, if nothing more…. Eugene held a special contempt for reviewers who did not adjust their big-city expectations to the earnest attempts of local productions or who failed to celebrate that major road shows had at least come to Mobile, however disappointing the performance.” ( Moon 276)

Walter’s willingness to abandon critical integrity did not stem from chauvinism or venality alone. It is possible to infer from a number of his acquaintances that his conversion to a lower standard was perhaps an unreflective outgrowth of his inner nature. Carolyn Haines, a regional novelist as well as compiler of Moments with Eugene , is not alone in her assessment.

“Eugene’s generosity toward other writers, other artists, other performers came from the huge capacity of his own heart, and his own talent. He had no need to belittle others, or withhold the wisdom he’d learned. He gave, plus praise and encouragement and hope to many, many people. ( Moments 109)

While her prose is poor, Haines’ sentiment sounds sincere enough, and fair. After all “Do What You Want For Best Results” was another one of Walter’s ironclad maxims. ( Moments 218)

In what only may be considered an act of grace, Walter wrote a generous tribute to his New London princesa in 1991 for an exhibition on Botteghe Oscure at the University of Texas even though she had accused him, falsely, of peculation to terminate his position at the journal all those years ago. ( Moments 282-83)

Zeitz also ratifies the assessment of Haines in describing his encounter with a designer for the Washington Opera who was working on a project in Rome. After a boozy, elaborate dinner with Zeitz, the designer and a number of other acquaintances Walter “charged the tab, no doubt, to the Washington Opera” then took Zeitz and the designer back to his apartment. All three of them were drunk. Zeitz found what ensued extraordinary, especially because he and probably Walter thought the designer “was clearly an asshole.”

Walter produced his black book.

“Worth a fortune, the black book was stuffed not only with its original blank text block but also a host of ragged cards and papers protruding from all three edges. The book literally bulged at the binding. In it were names, addresses, and descriptions of everything anyone needed to know about in Rome, Paris, and New York. The designer would say, I need costumes, or I need a location, or I need a really good photographer, and Eugene would page through his book and give him names and numbers. This amazing display went on for two hours.”

Equally amazing, “Eugene would tell the designer who to ask for, describe their English-language proficiency, and watch with disdain as the designer scribbled it all down.” Apparently even the most unpleasant and contemptible figure involved in the arts was entitled to assistance. Walter was, however, scrupulous in safeguarding his black book. During the entire tutorial “he never put it down; it never was out of his sight.” ( Moments 306-07)

19. Lasso The Moon.

Moments with Eugene succeeds in two interrelated but unintended ways, tarnishing Walter’s reputation by completing the historical record. His last years may amount to a sad coda, but they represent only the final act of an otherwise irresistible drama. And if some of Walter’s acquaintances engage, justifiably, in settling scores, most of them forgive his trespasses and remember him with deep affection.

It would be best, or more romantic, to remember Walter by Milking the Moon , for his charisma, inconsistent kindness and strange species of courage. He lived after all with no steady work, no safety net nor security of any kind. In reviewing the memoir, Yardley marveled at the magic that flourished where its subject lived as “the sole inhabitant of Planet Eugene.”

Yardley felt as if “ushered into what can only be called a state of enchantment.” He recounts the Bankhead story, and a story in which Walter finds himself alone on a bus in New York with Dame Edith Sitwell during a blizzard. “I had,” Walter explains, “been out shopping for castanets. That’s the story of my life: out shopping for castanets in a snowstorm.” (Yardley)

In case of snow.

It is as if he needed nothing so much as to act the playfully iconoclastic salonniere and impresario. In that endeavor he appears to have surpassed anyone then alive during his years in Rome. Zeitz recalls that with Walter “the conversation always seemed riveting and never seemed to end.” He also remembers Walter’s “undying energy to go out to the barn and put on a play… or a puppet show for Isak Dinesen.”

It would be difficult to dispute the assessment of Zeitz that Walter

“sacrificed great accomplishment in order to be able to live a grand life as he envisioned it: the life of a Southern boy and artist, the last embodiment of a superior civilization. He directed his surroundings--people, events, history, and art--to support his vital habits, his view of the world.” ( Moments 306-07; ellipses and emphasis in original)

It is somehow fitting that the title Walter gave Clark for his memoir is based on a song he wrote for Fellini’s “Juliet of the Spirits.” It was cut from the final version of the film.

Sources:

Anon., “Lincolnshire Stuffed Chine” (n.d.), http://slowfood.org.uk/ff-products/lincolnshire-stuffed-chine/ (accessed 8 March 2019)

Elisabeth Ayrton, The Cookery of England (London 1977)

Kathleen Carbone, “The Divine Spark of Nance O’Neil,” The Hatchet: A Journal of Lizzie Borden and Victorian Studies vol. 6, issue 3 (Winter 2009) http://lizzieandrewborden.com/HatchetOnline/the-divine-spark-of-nance-oneil.html (accessed 26 February 2019)

e. e. cummings, “I like my body when it is with your,” https://hellopoetry.com/poems/1590/i-like-my-body-when-it-is-with-your/ (accessed 18 march 2019)

George Daniels (“Introduction”), Gulf City Cookbook (Tuscaloosa facsimile 1990; orig. publ. Mobile 1878)

Thomas DeLeon, “Mobile--The Gulf City,” Harper’s Weekly XXXVII (2 February 1884)

Don Doyle, New Men, New Cities, New South: Atlanta, Nashville, Charleston, Mobile, 1860-1910 (Chapel Hill 1990)

John Egerton (ed.), Cornbread Nation 1: The Best of Southern Food Writing (Chapel Hill 2002)

Charles Baker-Clark, Profiles from the Kitchen: What Great Cooks Have Taught Us about Ourselves and Our Food (Lexington KY 2006)

Rebecca Barrett & Carolyn Haines (ed.s), Moments with Eugene… a collection of memories (Semmes AL 2000)

Bill Goldstein, “Castanets in a Snowstorm,” The New York Times (18 November 2001)

Jane Grigson, “Observer Classic,” The Observer (15 July 2001)

Tina-Kate Rouse, “Queen of Tragedy: The Career of Nance O’Neil,” The Hatchet: A Journal of Lizzie Borden and Victorian Studies vol. 2, issue 1 (February/March 2005) http://lizzieandrewborden.com/HatchetOnline/queen-of-tragedy-the-career-of-nance-oneil.html (accessed 26 February 2019)

Kim Severson, “In This Corner of Maryland, Holidays Mean a Stuffed Ham,” The New York Times (19 March 2018)

William Shakespeare, MacBeth (London 1606)

Eugene Walter, American Cooking: Southern Style (New York 1971)

Delectable Dishes from Termite Hall: Rare and Unusual Recipes (Townsend GA 1982)

Eugene Walter (Donovan Goodman & Thomas Head, ed.s), The Happy Table of Eugene Walter: Southern Spirits in Food and Drink (Chapel Hill 2011)

Eugene Walter, Hints & Pinches (Atlanta 1991)

The Untidy Pilgrim (Tuscaloosa 1981; orig. publ. 1953)

Tommy Weir, “On the Record: Eugene Walter” (YouTube 2009), www.youtube.com/watch?v=SpC_kwIHSPIE (accessed 28 February 2019)

Melissa Wittmeier, “The Art of the Table in Eighteenth-Century France,” Creative Commons vol. 38 (2010)

Jonathan Yardley, “The Life of the Party,” The Washington Post (19 August 2001)