An Occasional Miscellany from Dorset, indicating a number of things about eighteenth century foodways in the English shires.

Interests catholic and circumscribed.

In 1961 The Dorset Natural History and Archaeological Society published Dorset Dishes of the 18th Century. J. Stevens Cox edited the booklet compiled by others from manuscript sources and H.S.L. Dewar provided its eccentric introduction. Both of them were archaeologists and although it remains unclear, Cox may have been an illustrator as well. He took an abiding interest in the history and culture of Dorset, from its artifacts and folktales to Thomas Hardy and collected antiquarian books as well as ephemera about the county, including “a folio manuscript of Early 8th Century Cookery and Medical Recipes” kept by a Bragge family there.

Stranger things.

His interest in the subject of Dorset Dishes would appear logical enough but Dewar tries to disabuse readers of that assumption. Strange “is the fact,” he explains, “that the individual who first thought of the notion should, to all appearances, be indifferent to food, so long as it is not artificially whitened, ‘purified,’ or de-natured.” And yet those concerns would have entailed a lot more than indifference, especially in the context of early nineteen sixties England.

“But most strange of all,” Dewar continues,

“that I, a food-philistine who prefers kid to the lamb so fashionable in the Butcher’s [sic] shops, should be asked to write the introduction. So strange, that it is really absurd, save for the fact that in this

‘ …world empirical

Where fools are father of every miracle’

Anything can happen. It certainly can, and this is the fashion of it.” ( Dorset 1)

Stranger still perhaps, the booklet attracted the attention of Elizabeth David who, however, says nothing about it. Instead she reproduces a single recipe, “To Make Whipt Syllabubs,” with naked reference to its source. (David 231-32) That in itself is not strange; despite her pretention to intellectual rigor, David is capricious in her methodology and prone to elision as well as omission.

Across eighteenth century time in a single space.

Dorset Dishes is a tantalizing artifact because Cox himself strays from the systematic. The booklet identifies its manuscripts, including the Bragge folio, but provides date ranges for just four of the six. Three of them cover roughly the same years, from the outset until the middle of the eighteenth century while the fourth “in the possession of Mrs. Ivo Bond” is dated “Circa 1794.” An educated guess places one of the two undated manuscripts at midcentury and the other at its end because the dated manuscripts are listed in chronological order and so are the recipes taken from them in the text of the pamphlet. One of the undated sources appears listed after the three earlier ones, the other at the end of the list, which would place it later than circa 1794.

Recipes retardataire and revolutionary.

The nature of the recipes supports the timeline too, although without reference to the manuscripts themselves it is impossible to determine whether they are representative or simply caught the fancy of the compilers.

With that caveat it would appear that early nineteenth century Devon clung to the medieval practice of combining savory and sweet ingredients for a considerably longer time than London. Five of the eleven recipes from the manuscript that Cox kept do just that.

The Bragges sweetened their “Artificial Asses Milk,” presumably medicinal, with candied sea holly, which features “striking purple-blue flowers that look like small glowing thistles” with “a metallic sheen.” (Iannoli) Cox includes a carrot and a potato pudding that may be colored with saffron “if you have a mind to have it look like an orange pudding,” which would have been costlier than the potato. Sweet biscuits, citron, currants, dates, and candied orange peel along “with a little sugar” go into a white hog’s pudding while snail water, demonstrably medicinal, features dates, figs, raisins and more sugar. (Cox 5, 3)

In similar style a 1708 recipe sweetens its stock of beef and veal with currants, prunes and those raisins, called in these recipes variably ‘reasons,’ or ‘raisons’ and invariably “of the sun.” Cinnamon, clove and nutmeg spice the stock, finished with claret and thickened by grated white bread to sauce roast duck, lamb or pullet. (Cox 3, 6-7)

What, no pottage?

Once again the selective nature of Devon Dishes prevents definitive judgment but something distinctly medieval is missing . On its evidence pottage, the primus inter pares of English subsistence staples, looms large in its absence. At least three interpretations for the omission are possible.

Devon cooks may have been so familiar with the simple simmered stews based on grains, the lavish use of greens and herbs and might include almost any other savory ingredient that they saw no need to record how to make pottage. It may have remained a staple but only for the poorer sort; after all, it was chatelaines who drafted the manuscripts at issue in their big houses. Then again Devon cooks may simply have moved on to the more modern dishes by the outset of the century.

In contrast to the Medieval cast of the earliest manuscript the four Bond recipes at the other end of the century appear recognizably modern. None of them includes sugar and any of them, including an herbal compound butter with a trace of anchovy, a salad dressing and a spinach souffle, would appear welcome on the menu of an ambitious restaurant anywhere.

An English affinity for heat and spice.

All the manuscripts display the English affinity for highly seasoned and spiced dishes no matter their date. Anchovy adds depth to sauces or gravies for meat; cayenne makes serial appearances along with clove, mace and nutmeg; while green herbs in abundance perfume sauces and stews. One of them, a “Beef Trombton” scrawled sometime between 1710 and 1750, encapsulates English Enlightenment style; spectacular. It simmers flank and onions with a raft of root vegetables seasoned with clove, mace and peppercorns for five hours. The recipe incorporates a variety of green herbs at the outset and again at the end, to build a sauce from the stock along with anchovy and capers. Whatever or whoever Trombton was or is has become a mystery but the dish deserves revival.

Cucumbers for sale.

A regal and playful writer.

The same manuscript includes an equally appealing if more elaborate formula for “A Regalia of Cucumbers.” Its author, identified only as Mrs. Machen, drafted with a certain flair. Regal the recipe is, the cucumbers sliced “thick as a Crown” and fried with a dusting of flower in the fat remaining from a mess of caramelized onion with bacon; its author confides that “we sometimes do them without the Bacon.” The slurry to accompany the cucumbers is complete when you “toss ‘em up togeather with a little Claret and vinegar to your Palat.” ( Devon Dishes 12)

Mrs. Machen must have been fun. Along with her playful instructions in prose she set at least one recipe, called simply enough “Veal,” to ribald, apostate rhyme:

“Beg borrow or steal

A good Knuckle of Veal

In a few pieces cut it

In a stewing pan put it

Salt pepper & Mace

And what’s tacked to a place

Must season this Knuckle

With other herbs, muckle

That which kill’d King Will

And what never stands still

Some sprigs of that bed

Whence children are bred

And then you must mend it

With Spinnage & Endive

And Lettice & Beet

With Marygolds meet

Put no water at all

For it maketh things small

Which least it should happen

A Close cover clap on

Set your Pan or your Kettle

Be of honest Woods’ Mettal

And then let it be

Let the Doctrine I teach

About lett me see

Thrice as long as you preach

To skimming the fat off

Say Grace with your Hat off

Oh then with what rapture

Will it fill Dean & Chapter” (Devon Dishes 14)

A more than serviceable soup loaded with English herbs including the edible flower; “muckle” means a large amount in Scots dialect and William III died following a fall from his favorite horse, Sorrell.

But another mystery, at least at this point, is the herb that never stands still because of exertions in the conjugal bed. Readers are invited to explain. As for “Woods’ Mettal,” a further mystery. It is not the toxic alloy with a low melting point made from bismuth, lead, tin and cadmium, heavy metals all. That would await invention until 1860 for use as a soldering medium.

Rum and ruin.

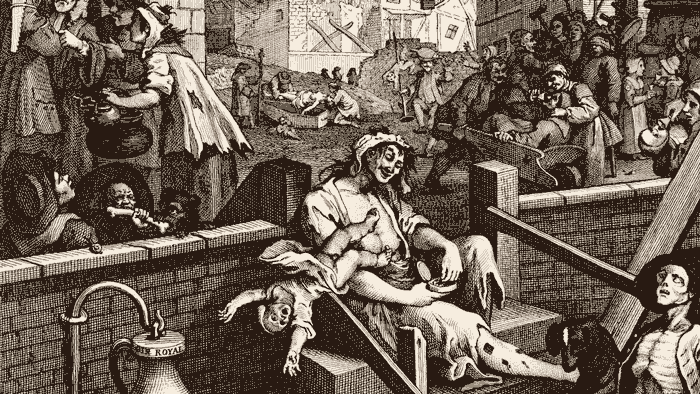

Some final fun from Mrs. Machen; she flavored cheese with rum, or maybe, almost certainly, not. Cox or his compilers take the leap that her usage of “ruin it with rushes” at the end of her recipe “To make a Rum Cheese” refers to rum, not an unwarranted assumption. Rum was associated with alcoholic ruin as early as the seventeenth century, although it was gin that became “mother’s ruin” in the age of Gin Lane.

Hogarth “Gin Lane”

The Oxford English Dictionary finds the first recorded reference to ‘rum’ in connection with the spirit in Connecticut during 1654 and of course written evidence trails verbal usage, sometimes for a long time.

Historical names for rum include what are likely its earliest, seventeenth century iterations; rumbullion, rumbustion and Kill Deuill, which also according to the OED was a common term along with its variations killdevil, kill the devil and others. Additional terms in circulation during the eighteenth century but not ruin include Barbados liquors or liquer and Barbados water--rum probably originated on the island during the 1640s--demon water, devil’s death, redeye and rumbo.

Cox and company likely erred in overlooking another meaning for rum that surfaced in the ‘canting slang’ of the criminal underworld a few years earlier than it appears in connection with the spirit. By 1637 the eighth edition of Thomas Dekker’s English Villainies refers to the term as denoting high quality or excellent. During 1698 ‘B.E.’ explicitly defines rum as “gallant, Fine, Rich, best or excellent” in A New Dictionary of the Terms ancient and Modern of the Canting Crew. ( Green’s )

Dekker digression.

Dekker is a wonderful figure, a prolific playwright and pamphleteer who also organized the Lord Mayor of London’s pageant for 1612 and 1627 through 1629. He collaborated with others on some fifty five plays and wrote at least nine of his own including The Honest Whore, Part 2 in addition to the several editions of English Villainies that included a “Canting Dictionary.” (“Thomas Dekker;” Green’s ) During “the war of the theatres” that raged during 1601 he satirized and was satirized by Ben Jonson, Jonson in The Poetaster , Dekker in retaliation with Satiro-mastix.

Villainies was not his only foray into the language of deviance and the street. According to Britannica “Dekker’s ear for colloquial speech served him well in his vivid portrayals of daily life in London” and he capitalized on a six year ordeal in debtors’ prison to write six prison profiles for Characters by Sir Thomas Overbury. In his pamphlets Dekker addressed themes as varied as the London theater scene, plague, “roguery and crime.” (“Thomas Dekker”) An eventful life.

To return to rum and ruin.

If ‘ruin’ does not appear as a specific synonym for rum, the spirit itself not appear in connection with cheese during the eighteenth century and the only current connection is with a Spanish producer that washes a sheeps’ cheese with the spirit. The use by a colorful Mrs. Machem of ‘ruin it with rushes’ seems--speculation--to indicate she either brushed or covered, the more likely move, her cheese with rushes, which were used for the purpose early in the history of cheese production. A shame about the rum though.

Early modern postmodernist ponderings.

Devon Dishes describes a savory ice cream from the middle to later years of its century for salmon that includes cayenne, horseradish and mustard could be mistaken for postmodern. Heston Blumenthal does something similar but, surprise, less sophisticated with his 2008 recipe for Pommery mustard ice cream, which he serves with a sort of red cabbage gazpacho saddled with frivolous froufrou. (Blumenthal 153) The eighteenth century salmon sounds better.

In case Devon Dishes isn’t available.

The meatless mince pies might be sourced from Fortnum’s; other desserts are comparably accomplished. The “Mackerooms” or macaroons also date to 1708 but are recognizably modern, the English burnt cream an exemplar of the ‘crème brûlée’ appropriated as its own by France. The syllabub that David cites is good.

Something of India, nearly nothing of France.

Mrs. Machem’s recipe for lemon pickle reflects the intrusion of empire; the technique and palette it paints arise recognizably from the Indian subcontinent. Other than the soufflé however and a “Gateau de Pommes” that instead of cake is a thoroughly English apple marmalade that “has been found excellent after five years’ keeping” ( Dorset 17) no French name for a dish or term of technique crept into the eighteenth century country kitchen on the evidence of Dorset Dishes. Wigs, as ‘Wiggs,’ soft little biscuits flavored with the traditional carraway, clove, mace and nutmeg do, along with other early modern English standbys including three flummerys and a number of sweet puddings.

Back to the savory side the compilers of Devon Dishes selected calf’s head, jugged hare (another good recipe), a tansy, potted venison and a rabbit disguised as “Boiled Cheese” but nothing remotely French. Only two fish dishes make the cut, both evidently English, for stewed carp and an appealing pie of herring marinated in vinegar, herb and spice; caveache in a crust. To drink; recipes for both elderberry and spruce beer along with sloe gin, anathema across the Channel.

Devon Dishes lends no support to the conventional wisdom that French technique gradually but inexorably infiltrated England over the course of the eighteenth century. Instead, by

“1781, English technique has swept all before it. ‘French cookery virtually disappears from the English scene. It is surely significant that although Carême worked for the Prince Regent from 1816 to 1817, his five cookery books were not translated into English. Later in the nineteenth century, Eliza Acton’s Modern Cookery devotes only about 15 pages out of 650 to foreign cookery.…The idea that French influence on upper-class cookery in England grew ever more dominant during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries is a myth.’” (Perkins 90-91; citation omitted)

Good recipes based on Devon Dishes appear in the practical.

Sources:

Anon., Green’s Dictionary of Slang , https://greensdictofslang.com/entry/ybgpzsq (n.d.) (accessed 7 February 2023)

Anon., “Thomas Dekker,” Britannica Online, https://www.britannica.com/print/article/156211(n.d.) (accessed 8 February 2023)

Heston Blumenthal, The Fat Duck Cookbook (London 2009)

J. Stevens Cox (ed.), Dorset Dishes of the 18th Century (Dorchester, Dorset 1961)

Elizabeth David, “Syllabubs and Fruit Fools,” An Omelette and a Glass of Wine (New York 1985)

Marie Iannoli, “How to Grow and Care for Sea Holly,” The Spruce , https://www.thespruce.com/grow-sea-holly-eryngium-4121081 (22 June 2022)(accessed 7 February 2023)

Blake Perkins, “London Taverns and the Dawn of the Restaurant Age,” Petits Propos Culinaires 121 (November 2021) 85-109