Factual fiction, featuring strange birds, narcotics, romantic foodways, a quack doctor & Things: Part 2 of 3.

A generous soul serves the glitterati.

Apparently the great publisher Joseph Johnson cared nothing about either fad or fashion even if some of his guests took a different view. From the early 1770s until the end of 1809 Johnson held a weekly dinner at three pm for friends, their friends and spouses, his clients and sometimes even the printshop staff.

Johnson did care about lively discourse across any ideological divide. The constellations that illuminated the Johnson dining room adjacent to St Paul’s cathedral in London are breathtaking if not the food he served. Although she does not disclose a source for the assertion Daisy Hay, his capable biographer, claims that Johnson never varied his menu. Occasionally, however, the staffers he indulged would engage in minor rebellion:

“Each week the fare consisted of roasted veal, boiled fish, boiled vegetables and rice pudding. There was wine to drink, although sometimes when Johnson’s shop staff joined the company they insisted on bringing their own beer--a ‘brutal’ practice, thought one more refined guest.” (Hay 1)

Hundreds of people sat at Johnson’s table over the years and he was, as the saying goes, ahead of his time in terms of feminism. This small, gentle man hung one of the most startling images of the age, Fuseli’s “Nightmare,” in his dining room. The voluble painter was his friend and frequent dining companion along with a coterie of radicals and reactionaries, visionaries, authors and polymaths.

The Nightmare

They include William Blake, Coleridge, Richard Edgeworth and his daughter Maria, who influenced Sir Walter Scott and later in life visited him at Abbotsford, “one of the most enjoyable experiences of her life.” Wordsworth made the pilgrimage to her County Longford holdings in 1829; in common with De Quincey after his initial infatuation “she was underwhelmed.” (Keown)

A Renaissance woman with Enlightened proclivities.

Edgeworth would acquire a role similar if more voluble but less extensive than Johnson’s. One biographer calls her in the 1820s “a brilliant centre for London society; as a talented anecdotist she entertained politicians and scientists.”

In addition to her practical endeavors as an Improving landlord, Edgeworth produced an array of pathbreaking novels along with educational tracts and hortatory moral fiction for younger readers. She also wrote and received a vast and varied volume of letters. Some of them advocated political and social reform, including remonstrances to ministers at Westminster. On the scientific front she

“maintained a lifelong correspondence with the Lunar Group, whose dispersed membership--based in the English midlands, of mechanical innovators and educationalists [sic] engaged with enlightenment practices--included her father… , Thomas Day (influenced by Rousseau), Dr Erasmus Darwin, the engineer James Watt, the industrial chemist James Keir, and the potter Josiah Wedgwood.” (Keown)

Back to the table.

Others who gathered around the Johnson table were Benjamin Franklin, William Hazlitt, Thomas Paine, Mary Wollstonecraft and Wordsworth, none of whom requires introduction; John Bonnycastle, a mathematician who relished sparring with Fuseli; the chemist Humphry Davy; Erasmus Darwin, both doctor and poet; William Godwin, a journalist, novelist and political philosopher, one of the earliest advocates of both anarchism and utilitarianism, and incidentally Wollstonecraft’s spouse; Joseph Priestley, “at once a philosopher, chemist, theologian, teacher and more;” and many other lights but not De Quincey. (Hay 2-4)

Their host became so celebrated as a publishing phenomenon and nurturer of talent that according to Hay “some among Johnson’s guests came to resent the way in which they were identified outside the walls via their presence in his house” even though “his labours allowed his visitors to make their voices heard when external forces threatened to silence them” through censorship, exile, imprisonment and violence. (Hay 5)

Dreaming spires and temporal gyres.

At Oxford, according to De Quincey “always elegant and splendid in her habits,” dinner would begin to appear later still, starting around 1805 or so. Colleges that

“had dined at four, now translated their hour to five. These continued good general hours, but still amongst the more intellectual orders, till about Waterloo. After that era, six, which had been somewhat of a gala hour, was promoted to the fixed station of dinner time in ordinary…. “

A fraudulent polymath demands punctuality.

It is more than a surprise that Palmer overlooked one of the more famous figures of the Regency in conducting his survey of the evolving dinner hour. William Kitchiner was celebrity enough for no less a figure than Cruickshank to caricature him several times. Kitchiner also drew the feigned ire of the famed Tory journal Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine.

Kitchiner has become widely regarded as little more than an eccentric but he was the paragon of a Romantic polymath. Also a fraud; although Kitchiner styled himself an MD and used the credential to promote a bestselling cookbook, he had earned no medical degree and also fabricated sojourns at Eton and Cambridge.

Regardless, the charismatic Kitchiner is a talented figure who earned membership in the Royal Society for his innovations in optics. He wrote or edited some fifteen books and essays on subjects ranging from the optics--including spectacle lenses, telescopes (he collected over fifty of them) and “How to Choose Opera Glasses,” optometry more generally and opthamology--to nutrition and peptic disorders; domestic economics; horse and carriage keeping; Maxims for Locomotion; incongruously “The Pleasure of Making a Will,” which he neglected to do and therefore died intestate; patriotic music including The Sea Songs of Charles Dibdin; and others.

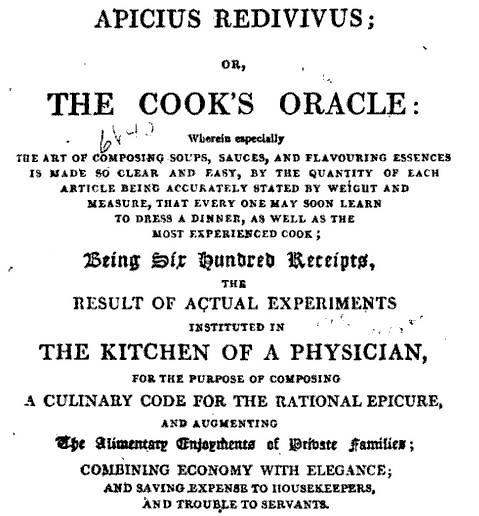

Most notably to posterity Kitchiner wrote Apicius Redivivus, or, The Cook’s Oracle, a discursive and delightful assay not only into cooking but also into the philosophy and ‘science’ of food interlarded with citations to classical antiquity, Shakespeare and more. It is a good cookbook that remained in print through several editions and remains a useful source of creative but distinctly British preparations.

Also an accomplished amateur musician, Kitchiner “collected with care a library of manuscript and printed music.” (Boase) He liked to greet dinner guests

“seated at his grand pianoforte, and struck up with ‘See the Conquering Hero comes’. [sic] For this performance, he usually wore silk stockings and pumps and had a contrivance underneath his pianoforte so that he could provide a drum and triangle rhythm worked with his feet.” (Bridge 7)

The flow of time… and wine.

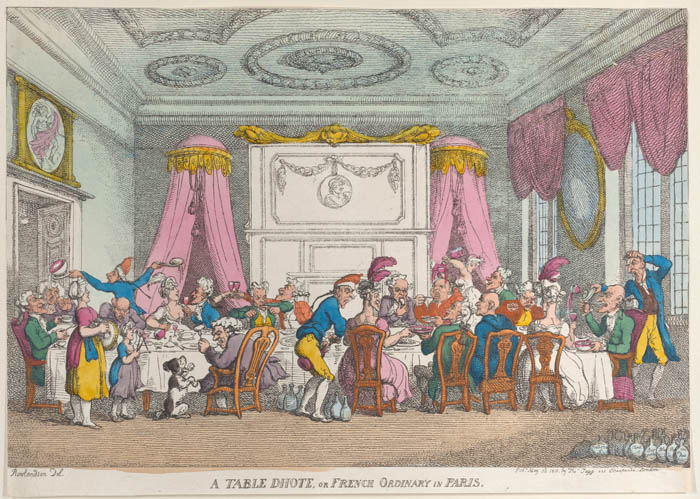

When dining alone Kitchiner usually ate at five pm; supper usually followed at nine thirty. In common with Johnson, he also held regular dinners for friends and acquaintances. Then, beginning in the second decade of the nineteenth century, Kitchiner convened a weekly Committee of Taste at his home in Camden. He began promptly at seven pm, locked the door against late arrivals and evicted his guests at eleven.

In its earlier years the Committee amounted to a laboratory for the Oracle; Kitchiner claims that the Committee tested each recipe in the book. Sometimes with the assistance of Henry Osborne, cook to Sir Joseph Banks, Kitchiner himself prepared the food he served and experimented with various dishes, sauces and wines. He even did the dishes, a task men of his station never undertook.

Not everything worked and according to a regular attendant the wines

“might be classed as good, bad and indifferent: some especially recommended because they were quite new--fresh from the docks--or tawny from antiquity, or mellowed by age, or having a peculiar bouquet, or ‘having eaten up their crust.’” (Jerden 283-84)

Diners imagined and real.

The diners were no less famous than the authors and artist Johnson supported. According to George Clement Boase, although he declines to identify them, Kitchener’s dinner companions formed “a circle of friends distinguished for genius and learning.” (Boase) Tom Bridge, co-author of an inadequate biography of Kitchiner, does identify some of them. He plagiarizes Boase in the process and speculates about the attendance of others including Byron, Keats, Shelley and Wordsworth but not De Quincey. (Bridge 11, 12)

The guests who did dine with Kitchiner as members of the Committee, which typically included six to eight participants, or in smaller informal groups. They include an array of theater people less well known today than his other companions but at least as equally celebrated in their time. John Braham was “the most famous tenor of his age;” George Colman a celebrated playwright; Charles Dibdin a playwright and impresario; Charles Kemble an impresario and actor; and Charles Mathews a famous comedic actor. Among other things Thomas Hood “wrote the burlesque Ode to Dr. Kitchiner.” (Bridge 15, 16)

Beyond the theater, novelist Theodore Hook, considered by Scott the “prince of lampooners,” was a member of the Committee for years before betraying his friend with a savage profile as editor of the “scurrilous” humor magazine John Bull in 1824. It was the second in a series that lampooned the famous. De Quincey had been first; Sir Humphry Davy would be third. Kitchiner had luminous company on both counts. Sir Humphry, baronet and President of the Royal Society, was a renowned chemist and inventor of, among other things, the pathbreaking and lifesaving Davy lamp. He first isolated the elements barium, boron, calcium, chlorine, iodine, magnesium, potassium, sodium and strontium. (Bridge 159, 159n, 163; Forward 248; Knight)

A poem.

The John Bull profile of Kitchiner ends with a “Sonnet to Conclude:

Knight of the kitchen--telescopic cook--

Medical poet--pudding-building bard--

Swallower of dripping--gulper down of lard--

Equally great in Beaufort [Kitchiner was born at Beaufort Buildings, Strand, London] and in book--

With a prophetic eye that seer did look

Into fate’s records when they gave thy name

By which you float along the stream of Fame

As floats the horse-dung down the gurgling brook,

He saw thee destined for the boiler’s side,

With beef and mutton endless war to wage;

Had he looked further, he perhaps had spied

Thee scribbling, ever scribbling page by page,

Then on thy head his hand he’d have applied,

And said, this child will be a HUMBUG OF THE AGE.”

(quoted by Bridge 162; Boase)

Scottish savagery.

The scabrous Blackwood’s, called simply Maga in its influential and notorious heyday, savaged Kitchiner too, or purported to savage him; with Maga it can be hard to tell. In “The Leg of Mutton School of Prose” John Gibson Lockhart associates The Cook’s Oracle with the Cockney School of Romantics including Byron and Shelley. He, and Maga, despised them, although Lockhart himself applied Romantic principles in his earlier work and admired both Coleridge and Wordsworth.

At the outset of “Mutton” Lockhart declares that Kitchiner “is the most unfit man in the world to write a cookery-book” and wonders why he has “forsaken the safe and beaten track of physic, to wander amid the wilds and mazes of cookery.” (Lockhart 563) The elevation of cook over doctor hints at what follows.

The thrust of the assault on the Oracle itself hits its detailed British character. “To come forward in the present day with a long and laborious treatise on roasting, boiling and stewing, (for prolix directions on these simple operations occupy four-fifths of the Doctor’s book),” Lockhart complains,

“is mere trifling at best…. Cooks, we trust, have too much taste and penetration to prefer the tedious prolixity of the Cook’s Oracle to the simple and practical recipes of Mrs Glasse and Mrs Rundell.” (Lockhart 566)

In reality Kitchiner’s recipes are no more prolix than those of either Mrs. Glasse or Mrs. Rundell, and Lockhart’s prediction that “what will be required of every future writer on the subject is, that he shall carefully study the cooking of the different European nations” elides the additional fact that neither woman covers anything but British dishes. (Lockhart 567)

Class consciousness…

Credulous readers consider Lockhart an elitist class warrior because he claims that “the productions of our country are insufficient for the gratification of more refined palates.” “For the rich,” Lockhart explains,

“there is no national cookery. The materials in our dishes are furnished by all the regions of the globe. In the compass of a single ragout are congregated the productions of every climate, and every soil.”

That is not the case for the poor: “The diet of the poor, indeed, is, and must be, regulated by the productions of the country in which they live…. But this is the law of necessity, not of choice.” (Lockhart 566)

The assumption of snobbery, however, is based on parodic passages rather than serious sentiment. Kitchiner, it turns out, is unfit to write a cookbook because he

“is a very hale and praise-worthy person indeed, possessing an excellent appetite and liberal mind, blending considerable knowledge with strong powers of digestion, and uniting the stomach of a horse to the nobler attributes of man.” (Lockhart 563)

Following a lengthy pseudoscientific exegesis on digestion with reference to nausea, vomiting, constipation and defecation, Lockhart insists that a “good cook… should be of weak digestive powers.” Only he, the stock caricature of a dyspeptic and disagreeable French chef, can manage the art of delicate cooking. (Lockhart 565)

“Trust not thy dinner,” Lockhart warns, “in the hands of a muscular and healthy cook,” who presumably eats what he prepares. “He will,” however,

“poison you with suet and hog’s fat--his dishes will be redolent of garlic and cabbage--all manner of abominations will assail your palate and your nose--your senses will become mere avenues of punishment--farewell the balmy stew, the mild and savory fricassee, the delicate, the stimulating ragout! There is death in the pot.”

Kitchiner or his cook is the poisoning kind of cook, while he and his Committee of Taste who approved the recipes for the Oracle, relish the abominations:

“If the Doctor will only tell us the names of the members of his illustrious committee, we promise never to dine with one of them should we live a hundred years. As a specimen of the taste of this club of foul feeders, we shall specify a few of those dishes which were devoured by them with unanimous applause. ‘Scotch Haggies,’ ‘Scotch Crowdie,’ ‘Ox cheek stewed,’ ‘Ox tails do.’ ‘Black Broth of Lacedaemon.’” (Lockhart 567)

…is not the case.

Academics of the class warrior school take those passages seriously. Brian Rejack repetitiously describes Lockhart’s review as an “implicit class-based assessment of Kitchiner’s unsophisticated palate” that has “unstated class implications.” “The unstated criticism,” he adds,

“hinted at by the distinctly French ‘transcendental “gout’ is that Kitchiner does not understand French cuisine. This inability stems from an apparent class difference--Kitchiner… lacks access to the fineries of Paris dining rooms and its newly developing restaurants.” (Rejack)

Resort to terms including “apparent,” ‘hint,’ “implicit” and “unstated” ought in general to invite skepticism in historical context. Rejack cannot have read the Oracle in particular or the considerable contemporary discussion of Kitchiner and his committee; his perspective is possible only when theory ignores context and replaces close reading. The word “gout” merely means taste and by 1823 was widespread in Britain; Kitchiner himself uses it in his Oracle. By then French terms but not French dishes had infiltrated British foodways. As Gilly Lehmann demonstrates, English cuisine had overtaken foreign influences. By

“1781, English technique has swept all before it. ‘French cookery virtually disappears from the English scene. It is surely significant that although Carême worked for the Prince Regent from 1816 to 1817, his five cookery books were not translated into English. Later in the nineteenth century, Eliza Acton’s Modern Cookery devotes only about 15 pages out of 650 to foreign cookery.…The idea that French influence on upper-class cookery in England grew ever more dominant during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries is a myth.’” (Perkins, “London Taverns” 90-91, quoting Lehmann)

It therefore comports with British practice that in fact Lockhart says nothing about France or French cuisine; it was not a factor. It also bears noting that the earliest Paris restaurants served the most fashionable food of the time in upperclass France, dishes from the English canon. After all the first restaurant in Paris was called La Grande Taverne de Londres. (Perkins, “London Taverns” passim) In any event Lockhart is not the hinting kind. If he wanted to score a point he would wield a bludgeon in the manner of De Quincey rather than wave a veil.

To the specific facts on the ground; Kitchiner did not cook leaden food, Lockhart likes the dishes described in his review other than an inside joke; and membership of the Committee would have been known to him because it and Kitchiner were famous.

The Oracle incudes a number of balmy stews, as the sly reference by Lockhart to the ox cheek and tail itself indicates, and several fricassees along with seven ragouts. Kitchiner also describes a sauce for service with the ragouts and a “savoury powder” along with its “quintessence” for making them. The powder consists of salt and pepper, allspice, cayenne, ginger, lemon zest, mustard and nutmeg, ‘materials furnished by all the regions of the world.’

As for the ragouts themselves, Kitchiner himself warns his reader to make them mild. “The Spices in a Ragout are indispensable to give it a flavour, but not a predominant one;--their presence should be rather supposed than perceived;--they are the invisible spirit of good cookery…. ” (Kitchiner 376)

Kitchiner does not mention crowdie, a mild farmers’ cheese, and the reference to black broth by Lockhart is classical and comedic.

A disgusting digression.

Kitchiner’s actual discussion of the broth indicates that by no means was it something he wanted anyone to cook. It is worth quoting in full:

“The BLACK BROTH of Lacedæmon will long continue to excite the wonder of the philosopher, and the disgust of the epicure. What the ingredients of this sable composition were, we cannot exactly ascertain. Jul. Pollux says, the Lacedæmonian black broth was blood, thickened in a certain way: Dr. Lister (in Apicium) supposes it to have been hog’s blood; if so, this celebrated Spartan dish bore no very distant resemblance to the black-puddings of our days. It could not be a very alluring mess, since a citizen of Sybaris having tasted it, declared it was no longer a matter of astonishment with him, why the Spartans were so fearless of death, since any one in his senses would much rather die, than exist on such execrable food.--Vide Athenæum, lib. iv. c. 3. When Dionysius the tyrant had tasted the black broth, he exclaimed against it as miserable stuff; the cook replied--“It was no wonder, for the sauce was wanting.” “What sauce?” says Dionysius. The answer was,--“Labour and exercise, hunger and thirst, these are the sauces we Lacedæmonians use,” and they make the coarsest fare agreeable.--Cicero, 3 Tuscul.” (Kitchiner 37)

Readers of Maga who in common with Lockhart would have shared a classical education also would have caught the reference to Lacedaemon.

Scottish delights.

Lockhart was a Scot sympathetic to its national project of the Romantic era. He wrote a biography of Burns and an acclaimed one of Sir Walter Scott, whose oldest daughter he married; they inherited Abbotsford. He also composed three volumes of Peter’s Letters to His Kinsfolk, an extended and sometimes serious satire of Scottish worthies, their mores and pretenses. It is apparent he had nothing against the national cuisine. Of a dinner in Edinburgh he writes that

“the provender was excellent. It consisted, primo, of broth made from a sheep’s head, with a copious infusion of parsley, and other condiments, which I found more than palatable, especially after, at my host’s request, I added a spoonful or two of Burgess to it.

Secondo, came the aforementioned sheep’s head in propria persona… a delicious, oily fragrant gusto worthy of being transferred, me judice, to the memorandum-book of Beauvilliers himself. These being removed, then came a leg of roasted mutton…. ” (Lockhart as Morris vol. 1, 22)

The Norwegians like it too.

Sheep’s head, as Boswell and Johnson could attest, was the dish most widely associated with the Scots kitchens of the age.

On another occasion Lockhart found another Scots dinner “excellent--a glorious turbot and oyster-sauce for one thing.” (Lockhart as Morris vol. 1, 66) Kitchiner includes recipes for both the fish and its sauce.

More ‘abhorrent abominations.’

After listing the selection of dishes favored by the foul feeders Lockhart quotes in full a recipe from the Oracle to drive in the blade. It is the kind of light suet pudding, eggy and studded with raisins from abroad, that was ubiquitous and universally enjoyed in the Britain of the time. Lockhart calls it a “mass of unvarnished abomination.” Nobody would have missed that joke either. (Lockhart 567)

Extending his parody of a bad review, Lockhart applauds Kitchiner for including medical

remedies in the Oracle.

“Aware, probably, of the coarse and abhorrent nature of most of the dishes detailed in his work, he has very judiciously recommended the exhibition of wonder-working drugs, to enable patients of weak stomachs to digest them.” (Lockhart 568)

Once again the satire would be obvious to the contemporary reader. The distinction between food and medicine was blurred; most cookbooks of the era include a section of medical remedies and a chapter on invalid food.

Toward the end of “Mutton” Lockhart quotes at length a set of amiable, commonsense recommendations for the dinner host, which only could have done Kitchiner a favor in terms of publicity. “If,” deadpans Lockhart, “the… directions are necessary, we cannot say we envy the circle of society in which we presume the Doctor forms the chief star.”

In closing his review of the Oracle Lockhart puts it down in its deserved place. “To the beau monde of these regions,’’ that is, the kitchen, scullery and housekeeper’s room, “we consign it. It is there, we believe, the Doctor most wishes to be popular, and we are sure it is there only it will succeed.” (Lockhart 569) The snobbery is feigned; Kitchiner emphasizes in the Oracle itself that he is writing for “the good housewives of Great Britain.” (Kitchiner 364) (emphasis original)

In other words, to its intended audience Lockhart recommends buying the book.

Another, generous, view of the ‘doctor.’

William Jerdan, another editor and author, at the Literary Gazette, remembers Kitchiner and his Committee with warmth in Men I Have Known. Jerdan knew a lot of men. Those he profiled include the great engineer Isambard Brunel; Canning; Coleridge; Thomas Cubitt, the architect of Belgravia; Dibdin; Hogg, the Scottish master of the sublime macabre and friend to Isobel Christian Johnstone; Scott; Sheriden; Southey; Wordsworth and others, although not De Quincey.

Jerdan considers Kitchiner a ‘great humorist.’ “Dr. Kitchener [sic]” Jerdan continues,

“was a character…., for medicating and book-making he had no equal: his medicating was book-making and his book-making medicating! But his medicating was not limited to two or three parts of the system: it was universal…. And he was exceedingly good-natured withal. Though occasionally a little petulant, he speedily forgave offense, and refraternized with the offender.” (Jerdan 282, 285)

Kitchiner dined with poets too, including Hans Busk, an intimate associate “descended from wealthy Norman aristocracy.” He copyedited all of the prolific Kitchiner’s work. One companion, Samuel Rogers, contributed to The Gentleman’s Magazine but declined the honor of Poet Laureate.

Kitchiner’s friend and mad-doctor.

By consensus Kitchiner’s closest friend was John Haslam, a distinguished doctor who “specialized in psychiatric disorder, or as Jerdan describes him “a very skilful mad-doctor, and almost as great a humorist as Kitchener [sic] himself,” (Bridge 11; Jerdan 285)

The power of science--and a scientist.

Another Committee member, Phillip Hardwick, designed both Euston and Victoria terminals along with their grand hotels. The greatest of the guests were Banks and Sir John Soane; the biggest celebrity among them the Prince Regent himself.

Banks was a brilliant botanist and natural scientist more generally who secured fame following his 1766 expedition to Labrador and Newfoundland, where he discovered the Great Auk (extinct by 1844), cataloged everything and sampled a strange dish called chowder for the first time. It captured his imagination. Banks believed it was “Peculiar to this Country,” meaning what would become Atlantic Canada. He liked chowder. It was “the Chief food of the Poorer” but “when well made a Luxury that the rich Even in England at Least in my opinion might be fond of.” (Perkins, “An Enquiry” 49, 50)

Later Banks sailed with Cook to Brazil, Tahiti and the antipodes, sponsored other expeditions, and like Davy served as president of the Royal Society, in his case with distinction for over four decades. During that time he also acted as a trustee of the British Museum.

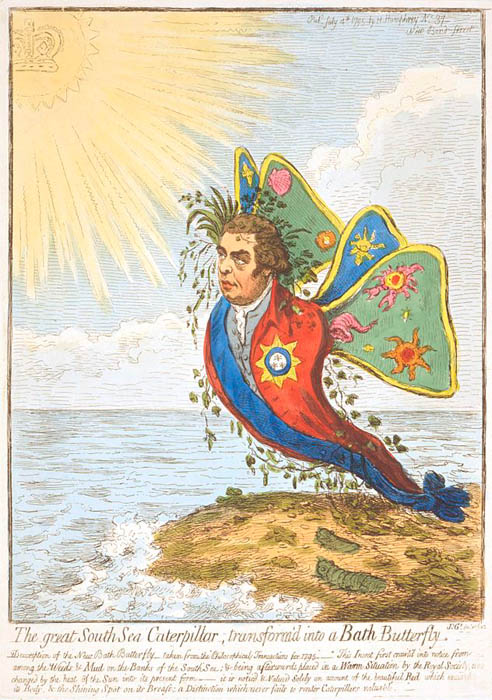

Gilray’s cartoon of Banks’s “transformation” after receiving the Order of the Bath.

Bridge derides Banks as “a very conceited person, conscious of his own importance,” but other authors omit mention of the trait so the notion will be tabled except to note its unlikelihood. Whatever his perception of self, Banks appears to have been devoid of snobbery or condescension--as his assessment of the chowder intimates. According to Simon Winchester he was “tolerant,” “near ubiquitous” in intellectual circles and “the most powerful figure in British science.” (Winchester 210, 266, 202)

Stratus and status.

Over the years Banks disregarded socially conservative opinion to develop an extensive network of friends and colleagues across class lines. One of them, William “Strata” Smith, was “condescended to and disregarded because of [his] class even when [his] work was acclaimed.” (Uglow) Not by Banks; from their first meeting in 1801 “until his death” in 1820 Banks “remained a steady friend and liberal patron of his labours.” (Winchester quoting John Phillips, Smith’s nephew and first biographer) Winchester considers those labors so important that he calls his biography of Smith The Map that Changed the World, but then it is fair to note that biographers tend to overestimate the significance of their chosen subjects.

Smith led a brilliant, tumultuous, tragic life. He worked not only as cartographer but also as “a consulting engineer on drainage and irrigation” and surveyor who searched on behalf of landowners for seams of coal and ores, on behalf of cities for well sites--his “predictions of water-bearing strata were invariably correct”--and on behalf of investors for canal routes. Early on his complementary careers led him to more scientific pursuits. (Uglow) Smith discovered that fossil remains could predict the geological nature of strata in the soil and accumulated hundreds of them until forced by debt to sell his collection.

A spendthrift like De Quincey, Smith however did not manage to outfox his creditors and avoid a term in debtors’ prison. He lived beyond his means in part by entertaining to win aristocratic patronage for his favored project, the first geological map of an entire nation. In that he succeeded, due to the early support of Banks, “support that would prove invaluable.” (Winchester 201)

A collaboration of Tristan de Lancey, Paul Smith and Peter Wigley has assembled the maps Smith drew across decades, now recognized aesthetic as well as scientific masterpieces, set beside contemporary drawings, engravings and illuminated with photographs, explanatory labels and essays in their massive Strata. Jenny Uglow is right to liken the “crazy grandeur” of Strata to “an exuberant fireworks display.” (Uglow)

Creative genius and cultural vandalism.

Soane, another eccentric, was arguably the greatest and inarguably the most creative architect of the age. The interiors of his house in Lincoln’s Inn Fields are among the most original on the planet and have influenced architects since he first designed them. In an act of cultural vandalism Sir Herbert Baker oversaw demolition of a masterpiece, Soane’s Bank of England, beginning in 1925. Only part of an exterior screen survived. The culprits knew what they were doing and inadvertently established their guilt by photographing every aspect of the breathtaking interiors before pulling them down.

The future George IV could claim genius but his birthright rendered him famous and he cut a scandalously louche figure. An unrepentant glutton and gourmand, he sought out Kitchiner instead of the other way around. Gillray caricatured him in one of his most famous cartoons.

A Voluptuary under the horrors of Digestion.

Whether or not the prince suffered serial dyspepsia it is unclear at what hour he dined with the ‘doctor.’

The food they ate.

It also is unclear what Kitchiner served the future king but Jerdan indicates that along with his experiments, often met with an element of suspicion, the optician offered his Committee traditional British selections. “The dinners,” Jerdan explains,

“were by no means as bizarre as rumour gave them out. If the oddities were there, there was always a fair counterbalance of the relishable and genuine. The very incongruities gave a zest to the treat.”

If Jerdan tolerated the oddities and incongruities he also was conservative when it came to his food:

“A tureen of soup… might be followed by a costly cut of Severn salmon, and there was generally a joint, to save you from experimenting with the made dishes, which, I must confess, seemed often to be of dubious quality, and rather dangerous to depend upon for a man with an appetite.” (Jerdan 283)

The Oracle itself, a complex combination of cookbook, comedy and digression, lies beyond the scope of this essay. The ‘made dishes,’ or combinations of ingredients--the stews. fricassees and ragouts purportedly beloved of Lockhart--appear in the Oracle but as Lockhart indicates Kitchiner by no means neglects other recognizably British preparations, from those roast joints to boiled turkey and lots of savory pies along with the steamed and boiled puddings absent from other cuisines; the list is long. He was a modernizer who hewed to tradition.

Kitchiner may have been best known for the condiments he carried everywhere in his ‘Magazine of Taste.’ Some of them, including “wow-wow sauce,” were his own creation.

Sources:

Jad Adams, “The English Opium Eater by Robert Morrison,” The Guardian (8 January 2010)

Anon., “Apperception,” AlleyDog.com,

https://www.alleydog.com/glossary/definition.php?term=Apperception (n.d.) (accessed 13 February 2023) Anon.,

“Last name: Somers,” SurnameDB, https://www.surnamedb.com/Surname/Somers (n.d.) (accessed 27 March 2023)

Anon., “Maria Edgeworth,” The Maria Edgeworth Centre, www.mariaedgeworthcentre.com(n.d.) (accessed 28 March 2023)

Anon., “thing,” The Chicago School of Media Theory,

https://lucian.uchicago.edu/blogs/mediateory/keywords/thing/ (n.d.) (accessed 22 November 2022)

Anon., “Thing Theory in Literary Studies,” Stanford Humanities Center: Arcade,

https://shc.stanford.edu/arcade/colloquies/thing-theory-literary-studies (“updated”) (accessed 22 November 2022)

Anon., “Thomas De Quincey, 1785-1859,” The History of Economic Thought, Institute for New Economic Thinking, http://www.hetwebsite.net/het/profiles/quincey.htm (n.d.) (accessed 13 December 2022)

Phil Baker, “Guilty Thing by Frances Wilson review--a superb biography of Thomas De Quincey,” The Guardian (23 April 2016)

Eric Banks, “Land of the Nod,” Bookforum (Sept/Oct/Nov 2016)

Maxine Berg, Luxury and Pleasure in Eighteenth Century Britain (Oxford 2005)

Tim Blanning, The Romantic Revolution (London 2010)

George Clement Boase, “Kitchiner, William, M.D.,” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 1885-1900, https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Dictionary-of-National- Biography,-1885-1900/Kitchiner,-William (n.d.) (accessed 21 February 2023)

Fernand Braudel, Civilization and Capitalism, 3 vol.s under separate subtitles (Berkeley 1979)

Tom Bridge & Colin Cooper English, Dr. William Kitchiner Regency Eccentric Author of the Cook’s Oracle (Lewes Sussex 1992)

Bill Brown (ed.), Things (Chicago 2004)

Jo Buddle, “An eccentric epicurean: the life of William Kitchiner (1777-1827), The Cookbook of

Unknown Ladies, https://lostcookbook.wordpress.com/2013/06/11/eccentric-epicurean/ (6 November 2013) (accessed 5 February 2023)

Frederick Burwick, Thomas De Quincey: Knowledge and Power (New York 2001)

Marilyn Butler, Maria Edgeworth: a literary biography (Oxford 1972)

Colin Campbell, “The Tyranny of the Yale Critics,” The New York Times Magazine (9 February 1986)

Dan Chiasson, “Hell of a Drug,” The New Yorker (17 October 2016)

Claire Connolly, “Maria Edgeworth was a great literary celeb. Why has she been forgotten?” The Irish Times (26 January 2019)

Theodore Dalrymple, “His gastronomical practice,” British Medical Journal vol. 345 no. 7869 (11 August 2012) 35

Elspeth Davies, Dr Kitchiner and the Cook’s Oracle (Durham 1992)

Tristan de Lancey et al, Strata: William Smith’s Geological Maps (London 2020)

Thomas De Quincey, “On Murder, Considered as an Art Form,” (North Haven CT 28 November 2022; orig. publ. 1827)

“Dinner, Real and Reputed,” http://www.authorama.com/miscellaneous-essays-6.html (accessed 1 December 2022); orig. publ. Blackwoods no. xlvi (December 1839)

Colin Dickey, “The Addicted Life of Thomas De Quincey: Chasing the dragon into a new literary realm,” Lapham’s Quarterly (19 March 2013)

Michael Dirda, “The fascinating life of an English writer, essayist and ‘opium eater,’” The Washington Post (30 December 2010)

Bonamy Dobree, English Essayists (London 1964)

Kenneth Forward, “‘Libellous Attack’ on De Quincey,” PMLA vol. 52 no. 1 (March 1937) 244-60

Neil Edmund Bain Halliday, “Fatal Consequences: Romantic Confessional Writing of the 1820s,” unpbl. PhD thesis (Univ. Birmingham October 2019)

Daisy Hay, Dinner With Joseph Johnson (Princeton 2022)

Rosemary Hill, “Spaghetti Whiplash,” London Review of Books (17 November 2022)

Richard Holmes, The Age of Wonder (New York 2010)

Giovanni Iamartino, “At table with Dr Johnson: food for the body, nourishment for the mind,” in Francesca Orestano & Michael Vickers (ed.s), Not just Porridge: English Literati at Table (Oxford 2017) 17-34

Jamie James, “Eating Opium and Writing Intoxicating Prose,” The Wall Street Journal (28 October 2016)

William Jerdan, Men I Have Known (London 1866)

Paul Johnson, The Birth of the Modern (New York 1991)

Heidi Kaufman & Chris Fauske (ed.s), An Uncomfortable Authority: Maria Edgeworth and Her Contexts (Newark DE 2004)

Edwina Keown, “Edgeworth, Maria,” Dictionary of Irish Biography, http://www.dib.ie/biography/edgeworth-maria-a2882 (n.d.) (accessed 27 March 2023)

James Ker, “Nocturnal Writers in Imperial Rome: The Culture of Lucubratio,” Classical Philology vol 99 no 3 (July 2004) 209-42

William Kitchiner, The Cook’s Oracle (London 1817)

David Knight, “Davy, Sir Humphrey, baronet (1778-1829),” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford 2004)

Gilly Lehmann, The British Housewife: Cookery Books, Cooking and Society in 18th-CenturyBritain (Totnes, Devon 2003)

John Gibson Lockhart, “The Leg of Mutton School of Prose. No. I. The Cook’s Oracle,Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine vol. X (August-December 1821) 563-69(writing as ‘Peter Morris’), Peter’s Letters to His Kinsfolk, 3 vol.s(Edinburgh 1819)

Robert Morrison The English Opium-Eater: A Biography of Thomas De Quincey (New York 2012) The Regency Years (New York 2019) (ed.) Thomas De Quincey: Selected Writings (Oxford 2022)

Sarah Moss, Spilling the beans: eating, cooking, reading and writing in British women’s fiction, 1770-1830, (Manchester Lancs 200)

Christopher Ott, The Evolution of Perception and the Cosmology of Substance (Bloomington IN 2004)

Valerie Pakenham, “Introduction,” Maria Edgeworth’s Letters from Ireland (Dublin 2017; Kindle edn. N.p.)

Arnold Palmer, Movable Feasts (Oxford 1952)

Blake Perkins, “An Enquiry into the Derivation of Chowder,” Petits Propos Culinaires no. 109(September 2017) 32-67“London Taverns and the Dawn of the Restaurant Age,” Petits Propos Culinaires121 (November 2021) 85-109

Diane Purkiss, English Food: A People’s History (London 2022)

Brian Rejack, Gluttons and Gourmands: British Romanticism and the Aesthetics of Gastronomy, unpubl. dissertation, Vanderbilt University (Nashville 2009)

G. J. Renier, The English: Are They Human? (London 1931)

Lee Sandlin, “Seductively Dangerous: Without Thomas De Quincey there would have been no James Frey,” The Wall Street Journal (11 December 2010)

Robert McG. Thomas, “René Wellek, 92, a Professor of Comparative Literature, Dies,” The New York Times (16 November 1995)

Jenny Uglow, “The Reader of Rocks,” The New York Review of Books (11 March 2021)

Sarah Wasserman, “Thing Theory,” Oxford Bibliographies, https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/view/document/obo-9780190221911/obo-9780190221911-0097.xml (24 June 2020) (accessed 22 November 2022)

Frances Wilson, Guilty Thing: A Life of Thomas De Quincey (New York 2016)

Simon Winchester, The Map that Changed the World (New York 2009)