Festive miscellany: Robin McDouall on the secular & profane pleasures & pitfalls of Christmas.

During the late 1950s and early sixties, Robin McDouall wrote a number of occasional essays on food, drink and travel for The Spectator. McDouall then was in the midst of his long tenure as secretary, or manager, at the storied Travellers Club in Pall Mall. He also found time to write for Harper’s Bazaar and what then was the Glasgow Herald on the same and similar subjects.

In November 1962 McDouall turned his attention to the holidays with a typically humorous but in part uncharacteristically somber meditation on “Un-Christmas visits.” The contingency of place, of location, is the purported focus but McDouall also takes a humane turn to consider the impact of people.

In conclusion he confesses that “the more I think of the places where I am glad not to be spending Christmas, the more grateful I am to my beloved friends and their kind hospitality.” They are not identified but live in “one of the pleasantest houses I know.” McDouall plans to spend five days there: “The food is delicious. There is limitless drink.” There are servants too, praise god, reliable heat and hot water. The anticipation of hospitality and fellowship set him a reflective frame of mind.

It would be terrible to spend Christmas in Switzerland; the snow, the mountains, the skiing would be bad enough, but what would cause “even greater alarm is the après-ski life: drinking hot wine in hot night-clubs with hot German girls in hot sweaters doing the twist.” (McDouall)

It’s getting hot in here….

2. Proclivities.McDouall was openly gay in a tacit way but does not describe himself as such in print, an understandable enough exercise of discretion given his times. Hugh Massingberd, editor of Burke’s Peerage, nonpareil obituarist and author of some forty books, most of them about the aristocracy, describes him as “splendidly camp” and his manner as “simpering,” while also prone to divulge that “I don’t mind paying for it, but he has to be a gent.” (Massingberd n.p.; emphasis in original)

Massingberd, “a considerable raconteur” satirized variously in Private Eye as ‘Massivesnob’ for his work at Burke’s and to his delight as ‘Massivepecker’ for the obvious reason, adored the Travellers as much as he adored aristocratic genealogy, the theater, actors of all stripes, (Jeremy Paxman describes him as a Stage Door Johnny desperately on the hunt for autographs), literati, the racetrack and cricket. His love of McDouall’s club entails a certain irony. “The cross-Channel trip required for membership,” Paxman also notes, “was clearly an ordeal.” (Paxman; Vickers)

Most of all Massingberd “loved food compulsively,” at least according to his friend and fellow obituarist Hugo Vickers, who describes him as “thin and drawn-looking” at the age of twenty- four. (Vickers) Massingberd himself, in his own obituary, describes his physical trajectory: “Tall, thin, and slightly dandiacal in his prime, he eventually sacrificed his figure in the cause of a quite alarming gluttony.” (Fergusson)

At one point Massingberd had eaten the biggest breakfast in the history of the dining room at the Connaught Hotel. Breakfast more generally always was itself alarming. “If a waiter listed the menu for breakfast eggs, sausages, bacon, steak, mushrooms etc [sic],” recounts Vickers,

“Massingberd merely nodded. When the waiter enquired which he wanted, he would say, ‘All of them’, and then worked his way through them.”

One evening Vickers invited him and two other friends to share a brace of pheasants; Massingberd ate one, the other three the other; Vickers “suspected he went to McDonald’s, ravenous, on the way home.”

By the time of his death at the early age of fifty-one Massingberd weighed 320 pounds. (Vickers)

3. Sensibilities.

Sexual preference does not account for McDouall’s distaste of the girls dancing at the disco, which instead arose from the High Tory cultural sensibility he shared with most of his many friends. He indulged priestly indiscretions at the Travellers, including a chapel hidden behind a cupboard where a catholic recidivist performed illicit Latin rites. McDouall also orbited not only with members of the club he ran but also with the rural gentry and some rarefied aristocratic socialites. (Scruton)

Other places might be nearly as bad as Switzerland for the holidays. Christmas in a hospital or a sixties seaside hotel, where the kitchen invariably vomited “a fragment of fish… garnished with a pickled walnut,” then “a piece of battery turkey, laced with Bisto” followed by “a parody of plum pudding, draped with photo-paste enlivened with rum” would count as gruesome. It was not an age of prowess in British hotel dining rooms but the festivities could compensate for the flaccid food.

After dinner

“the fun really begins: cotton-wool balls, paper streamers, balloons. All one’s pent-up hatred can be indulged. Ha! Got old Miss Beagle on the nose--too bad it wasn’t a stone. Hurray! Landed a streamer in Mrs. Bogle’s sparkling moselle. Bang! There goes cute little Mavis’s balloon.”

This form of celebration would have been replicated at sea but the ship might offer one advantage. “Christmas on a cruise must be much the same, except that there is a chance of jumping lightly overboard and getting away from it all.”

4. Wideboys and bananas.

Preferable to a cruise.

Preferable to a cruise.

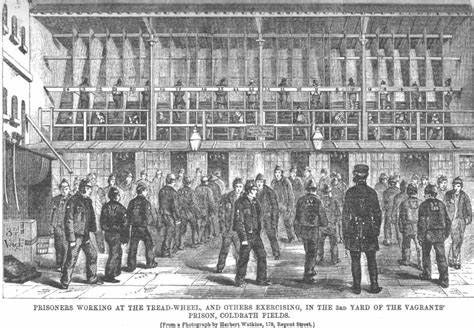

Prison also would be grim, although maybe not as grim. In prison at least, where the “‘halls’ have been decorated with Christmas trees, holly and streamers,” the kitchens have done their holiday best, if at the price of delayed gratification: “For some weeks the food has been even worse than usual so that the caterer could save up to provide roast pork and a super duff on Christmas day.”

Duff, traditionally associated with ships’ galleys in the age of sail, also is synonymous with plum, or Christmas, pudding, so that the caterers have gone to lengths indeed, also, perhaps, providing “a great treat” in the form of a banana or an orange. And unlike American pens, H.M. Prisons are not quite dry. “There will be a glass of ginger wine,” strong and cheap and not to be despised, “to add to the festivities,” while McDouall hopes “the wider boys will… have smuggled in half bottles of whisky.”

The cons will have sacrificed to contribute to the occasion in licit ways as well:

“Cells will be decorated with Christmas cards from loved ones and tobacco will be scarce because of the Christmas cards that have been bought for loved ones with tobacco money.” (McDouall)

Not quite gifts of the magi but no less moving for that.

5. Avoidance therapy.

Some things, or actually people, as well as places could be worse than prison. Unlike Massingberd, McDouall is no worshiper of authorial authority so is careful on Christmas day to avoid disagreeable characters including Evelyn Waugh, Somerset Maugham, F.R. Leavis and for that matter all of Cambridge, where Leavis taught at Downing College. At his best he always had been a moralistic prig; by 1962 a radioactive Leavis was considered “fanatic and rancid” in the more compassionate circles of the academy. (Seymour-Smith 291-92)

Looking back from 2011 on his Cambridge years from 1978 until 1982, the incomparably subversive Stephen Fry found Leavis even more unbearable and marginalized, a “sanctimonious prick of only parochial significance.” (Fry 46)

Sir Albert Richardson, the rigid neoclassicist who may have been the first of the Young Fogeys, would be unwelcome by McDouall at Christmas. Perhaps the frock coat and top hat, or sedan chair the portly architect favored for traveling to parties put him off.

Some female figures from an aristocracy that Massingberd esteemed require avoidance as well. No presents from McDouall for Lady Munnings, her horses and hounds or singing dog; none for Lady Dartmouth, Lady Docker or the Duchess of Argyll.

Acid Raine, Lady Dartmouth.

Raine Dartmouth, the only daughter of the talentless Barbara Cartland, was renowned for her bad taste. Following a later marriage to John Spencer her stepchildren including Diana called her “Acid Raine” and, for their first Christmas together, gave her a biography of Marie Antoinette. Diana’s brother Charles described “the wedding cake vulgarity” of her decorating style. (“Raine Spencer”) Sympathetic observers regard her as earthy and unpretentious in contrast to the snobby and status obsessed but vapid Spencers. (See, e.g., “Raine Spencer”)

Norah, Lady Docker, was an extravagant grifter obsessed with publicity. After her stint as a dance club ‘hostess’ she married three times, most notoriously to Sir Richard Docker, chair of the company that built luxurious Daimlers for the rarefied end of the car market. The tabloids called her ‘naughty Norah’ but not for the usual reasons related to sex. According to Martin Celmins at The Independent, Lady Docker “never even undressed in front of her husband.”

Even so the couple appears to have been compatible. “Their lives,” Celmins continues, “were a series of publicity stunts.” The biggest of all was a party thrown on their 863 ton yacht for forty-five coalminers. “I did my darndest,” wrote a correspondent for the Daily Mail who attended the revels, “to see if I couldn’t squeeze a sneer from these colliers, suddenly cast into circumstances of almost appalling luxury. I failed. I failed completely.” (Celmins)

The miners were not alone. The public adored the Dockers for their “exuberant and extravagant” behavior, not least the scandals. The couple drove around in a fleet of custom Daimlers, one of them The Gold Car decorated with 7,000 gold stars and trimmed in gold rather than chrome. The Golden Zebra she got one Christmas also was trimmed in gold. It had an ivory dash and naughty Norah had had it upholstered with zebra hide because, she explained, “mink is too hot to sit on.” (Buckley)

She charged Daimler some GBP 8,000, more than the average cost of a British house at the time, for the clothes she ordered one year to wear at the Paris Motor Show because, she insisted, she “was only acting as a model” on behalf of the firm. (Stepler) The castle she bought and redecorated with the firm’s money cost over three times more than the Paris couture. (Delingpole)

The unabashed looting of her husband’s company, a practice that would result in his ouster and their decline into destitution, contributed in no small amount to their notoriety. The ban from Monaco following bad behavior during a royal wedding added further to her fame. Lady Docker lost her husband after thirty years of marriage and survived him by only four; “almost to the end, she drank her favourite pink champagne.” (Celmins)

Argyll, called Margaret Campbell, who does not appear to have had many redemptive traits, takes the biscuit for dramatic deviance. Her heroic sexual career began at age fifteen with David Niven. “All hell broke loose,” according to the family cook, due to the ensuing abortion. (Thornton)

Treacherous and lecherous, the duchess reveled in her status as a scandalous socialite. “Her feuds with her family, her landlords, her bankers and her biographers were,” according to The Telegraph, “all lovingly documented, usually with her own connivance.” (“Margaret Duchess of Argyll)

Unburdened by any sense of tact or humor (Spence), the duchess never lacked confidence. She remained unabashed to the end:

“I had wealth. I had good looks. As a young woman I had been constantly photographed, written about, flattered, admired, included in the Ten Best-Dressed Women in the World list, and mentioned by Cole Porter in the words of his hit song ‘You’re the Top’. The top was what I was supposed to be.” (Campbell)

She did not exaggerate. Her wedding in 1951 was a national sensation--the gown with its eight and a half foot train is in the costume collection of the Victoria & Albert Museum--and remained a figure of fascination throughout her life. It was a shallow one. “Always a poodle, only a poodle! That, and three strands of pearls” were, she insisted, “absolutely the essential things in life.”

She freely admitted that she was “always vain.” (Dukas) Joe Hill-Gibbons, one of her most sympathetic biographers, adds that the duchess was “manipulative and snobbish in the extreme.” (Hill-Gibbons) Others agreed. David Randall says her Tatler column, “even for that publication, stood out for its snobbish banalities,” while reviewers derided her memoir, Forget Not, as forgettable. It is encumbered by more snobbery along with namedropping and an attitude of unjustified entitlement.

Randall describes the duchess and her short lived duke (their marriage lasted but three years) as “a pair who had rank, position, money, a stately home, but no class.” For his earlier marriage, to the 18 year old daughter of Lord Beaverbrook, the duke had taken his new wife “to spectate at a French brothel” for their honeymoon, then during their eight years of marriage “spent her money, pawned her jewelry and knocked her about.” (Randall)

The Duchess’s signature pearls (and clothes for a change).

Margaret would prove a more formidable foil. Possibly from the side effect of a fall, her credo would become “Go to bed early and often,” and she did. (“Lipstick”) After a handful of earlier affairs, as Randall explains,

“by the early mid-1950s, she was extremely busy, her lovers including Bob Hope, Maurice Chevalier, a fair percentage of the men of Inveraray (the town near the Duke’s seat of the same name), an unnamed member of the Royal Family, even passing teenage holidaymakers.”

One of them, then 17 years old, recalls encountering the duchess, who offered him a drink and hot bath, in Oban during 1958. He accompanied Margaret to her castle: “No sooner had he started to soap himself in the castle’s pink tub than the unclad duchess stepped into the bathroom with her intentions clear. Hospitality indeed.” (Randall)

During divorce proceedings the duke stole a number of Polaroids shot in the mirrored Art deco bathroom (a recurring theme) of his wife’s Mayfair pied a terre. Two in particular and a narrative series entranced both press and public. One depicted the duchess wearing only her signature strands of pearl; another documented her, again wearing pearls alone, going down on a man whose head was cropped from the photograph; he turns out to have been Minister of Defence at the time.

The series depicts another headless man, who turned out to be Douglas Fairbanks, engaged in various stages of masturbation. Fairbanks had provided each image with a handwritten description just for the duchess, from “thinking of you” through to “finished.” (Kirby; Randall; Hall)

Scandalous at midcentury, all of these antics would gain her admiration in certain quarters today. But for her ghastly personality, Christmas with the duchess may not have been so bad in some respects. In the least it should not have proven uneventful.

6. The inhumanity of solitary confinement.

McDouall closes on a plangent note. Sometime, some day, even a member of his harridan collective, might be welcome at Christmastime after all, although Argyll probably would appear last on his list.

“One possibility I have left out because it is almost too terrible to be thought of,” he confides: “I am glad not to be spending Christmas alone. Many are.” (McDouall)

Sources:

Anon., “Lipstick on her collar,” The Independent (30 June 1995)

Anon., “Margaret Duchess of Argyll” (obituary), The Telegraph (28 July 1993)

Anon., “Raine Spencer: Friend not foe,” The Independent (15 December 2007)

Martin Buckley, “The gear box: Christmas on wheels--Docker Golden Zebra,” The Telegraph (25 November 2006)

Martin Celmins, “Rear Window: Flash, brash, and fawned over by Fleet Street--When scandal wasn’t royal,” The Independent (12 December 1993)

James Delingpole, “Castle for keeps,” The Telegraph (12 May 2007)

Sarah Hall, “‘Headless men’ in sex scandal finally named,” The Guardian (6 October 2008)

Terry Kirby, “For sale: London residence where Duchess scandalised society,” The Independent (6 February 2004)

Robin McDouall, “Un-Christmas visits,” The Spectator (23 November 1962)

Hugh Massingberd, Daydream Believer: Confessions of a hero-worshipper (London 2001), https://books.google.com

Jeremy Paxman, “The fine art of speaking ill of the dead,” The Observer (4 November 2001)

David Randall, “The scarlet Duchess of Argyle: Much more than just a Highland fling,” The Independent (17 February 2013)

Jack Stepler, “Wife’s Spending Blamed--Sir Bernard Docker Bounced From Post,” The Calgary Herald (1 June 1956)

Michael Thornton, “Did David Niven Plot to Murder His Wife?” Daily Mail (11 June 2011)

Note:

Some citations, although no quotations, have been taken from Wikipedia alone.