Food at sea in the age of fighting sail

Few subjects have been more misunderstood than the diet of ratings and their officers on board Royal Navy vessels during the ‘long eighteenth century’ from 1688 until 1815. It makes a good story, particularly from the onset of the French revolutionary and Napoleonic wars, when British warships remained on station for unprecedented durations, both to enforce the blockade of France and its continental possessions, and to fight its fleets in the Caribbean and Mediterranean seas.

1. The camps…

Conventional wisdom has conceived of Royal Navy ships as ‘floating concentration camps’ manned by miserable and frequently coerced sailors subject to brutal, and brutally arbitrary, discipline at the whim of sadistic captains. They and their officers may have eaten well and even lavishly, but their men subsisted on substandard stores of rotten meat and weevilly biscuit.

As recently as 2007, for example, Noel Mostert described the diet of Royal Navy sailors during the period from 1793 through 1815 as “repellent and nutritionally barren.” His salt meat is nightmarish. “Darkened and hardened by age, these lumps bore little resemblance to meat. It required long soaking… by which time its resemblance to anything nutritious was nonexistent.” “Biscuit presented a similarly sorry tale…. As it aged it bred weevils and, growing still older, the weevils metamorphosed into maggots.” (Mostert 92; but see Editor’s note) Mostert characterizes the ratings themselves as sozzled louts. “It was never difficult for a sailor to get drunk on any day he wished.” (Mostert 92)

As recently as 2007, for example, Noel Mostert described the diet of Royal Navy sailors during the period from 1793 through 1815 as “repellent and nutritionally barren.” His salt meat is nightmarish. “Darkened and hardened by age, these lumps bore little resemblance to meat. It required long soaking… by which time its resemblance to anything nutritious was nonexistent.” “Biscuit presented a similarly sorry tale…. As it aged it bred weevils and, growing still older, the weevils metamorphosed into maggots.” (Mostert 92; but see Editor’s note) Mostert characterizes the ratings themselves as sozzled louts. “It was never difficult for a sailor to get drunk on any day he wished.” (Mostert 92)

2… were not camps.

It takes scant insight to question this depiction of the dominant strategic force of the age. British commanders never hesitated to take the weather gauge, superior in attack but hazardous for retreat, and aimed their guns to kill their opponents and sink their ships rather than prevent them from pursuit. British ordnance shattered hulls rather than toppling masts. The navy encouraged its captains to take individual initiative even in large fleet actions and Nelson famously encouraged them to engage the enemy more closely as their default tactic. This aggressive doctrine was feasible only because the Royal Navy was confident in the superior competence and morale of its crews. The notion that tortured and starving addicts could function at so high a level is scarcely credible. Then again, runway models make a lot of money.

3. The life was not so bad.

N. A. M. Rodger put paid to the first myth with his exemplary Wooden World. In reality the British fleet was not such a bad place to live, particularly at sea, by the lights of the day. “Life for the common seaman in the Royal Navy was nothing like so hard as life in the merchant service. The much larger crews meant that there were more men to share the heavy jobs, and a sadistic captain was likely to find himself court-martialed.” ( Black Flag 134) Life was brutal and contingent in a brutal age, but less so in the senior service, where at least a man was assured of his ‘three square meals’ each day, a term derived from the reliability of sustenance in the navy and the square wooden plates with nailed battens that ratings used to eat their food. (Macdonald 110)

Officers went to considerable length to ensure that food was served out equitably to their crews, sometimes to the disadvantage of the officers themselves. The great admiral John Jervis, Earl St. Vincent, demonstrated both a “domineering and ruthless personality” and a “great concern for the welfare of his men.” (Lavery 205, 206) His standing orders as commander of the Mediterranean Fleet during 1796-98, for example, include detailed instructions for the distribution of food.

When captains ordered the killing of cattle on board ship, St. Vincent ordered the officers to take the head and tongue as their share in order to reserve the choicer cuts for the men, “he taking a head every slaughtering by way of example.” (‘16 June 1797;’ Lavery 214) Similarly, in distributing the lemons crucial to the prevention of scurvy, “no consideration is to be had to the officers in preference to the men but they are to be equally apportioned to the number of persons victualled, with a reserve for the sick.” (‘14 th June 1796;’ Lavery 210)

4. The food was pretty good…

Janet Macdonald has disproven the second myth, of inadequate amounts of spoilt food, in Feeding Nelson’s Navy . Her primary research is impressive and her prose brisk: Unlike Mostert’s effort, this is a work of serious history that is a delight to read. Macdonald points to records about the spoilage of preserved shipboard foodstuffs (rare), the health of the crews (good, especially from the end of the eighteenth century on) and the Victualling Board regulations (scrupulously fair to the ratings). By her calculation, enlisted sailors on Royal Navy ships consumed a robust average of something like 5,000 calories a day. (Macdonald 177-78) The quantity apparently was there; what about the quality?

She cites the absence of mutinies in the British fleet caused by complaints about food and the strenuous efforts of commanders, not least Nelson (who had a particular faith in onions), to supply their ships at sea with fresh provisions of produce and meat for the entire crew. Packet boats from England brought fresh food to the Channel Fleet and some captains kept gardens ashore along their assigned cruising lanes to supply the crews with vegetables.

Most captains shipped livestock of all kinds and the fodder required to keep them alive for fresh food into the reach of long journeys, despite the considerable risk that the ratings would adopt them as pets. In a charming aside, Macdonald notes that many captains “found the poultry-keeper (known as ‘Jemmy Ducks’) had to be changed regularly, lest he grow too fond of his charges.” The phenomenon also tells us that captains were not the totalitarians of popular myth; at least one pig was so popular with its crew that she died onboard off China of obesity. (Macdonald 130, 131)

Finally, local populations eager to trade, and often undeterred by belligerent status off the French and American coasts, rowed bumboats selling all manner of food out to warships eager to buy.

Economic as well as nutritional factors motivated the navy to find supplies of fresh food for its ships. It is anachronistic to consider preserved food in the eighteenth century cheap compared with a fresh alternative, as it is today. In fact it was considerably more expensive. Before the advent of canning, sterilization and refrigeration, it was costly to salt or cure meat and to dry peas or fruit like raisins. Even now cheese, then a standard ration, is more expensive than milk. Problems of spoilage had become so acute that during the eighteenth century the Royal Navy baked its own biscuit and stamped each one with the broad arrow (‘crow’s foot’ to the crew) marking at as property of the Crown.

Rodger explains that an “astonishing” rate of spoiled food shipped in cask, for example some 1 per cent from 1750-57, was “achieved by great care in the manufacturing process (backed by continual experiment and development) and by using only the most expensive ingredients. The Admiralty declared ‘their intention that the seamen should be supplied with the best of everything in its kind,’ and in general they were.” ( Wooden World 85) Elsewhere Rodger notes that during the period from 1649 until 1815, “British naval victualling is a remarkable story of rising standards, making ever more extended operations possible.” ( Command 306) All of this resulted from the creation of “an extremely expensive and sophisticated machine” that became the largest buyer of agricultural products on the London market. ( Wooden World 82; Command 307)

The pictorial record supports Macdonald and debunks the conventional wisdom too. Thomas Rowlandson, the political cartoonist famed for his unflinching portrayal of the human condition, humor and irreverence, created a series of watercolors depicting the “various ranks and trades” of the Royal Navy in 1799. ( Black Flag 8) His sailors are hardly malnourished: The cook is, in the parlance of our times, ripped. His forearms and biceps bulge with defined muscle, along with his calf, and cords of sinew line his neck. This is all the more remarkable because the navy traditionally recruited its cooks from the ranks of seamen disabled by wounds. Rowlandson’s is no exception: He has lost a leg. If even a disabled seaman boasted such a physique, he cannot have been subsisting on an insufficient number of empty calories.

5… except on French ships.

Macdonald also compares the food of the Royal Navy to the food of its contemporaries in France, the Netherlands, Spain and the United States. Extant records indicate that the lot of their sailors was similar but for France, whose seamen suffered the kind of rations mythically ascribed to their British antagonists. Food shortages bedeviled the French Navy following the Revolution for various reasons including the conscription of farmers and British blockade. Food shortages and scurvy prompted a mutiny in the French squadron off Brest in 1793, and British blockade squadrons found the illness among French prisoners then and in 1795. (Macdonald 147-48)

As to the food itself, “[i]t was often very bad, due to dishonest supply officers whose practices included resupplying food which had been condemned and returned to stores…. French crews who captured British ships during the wars of 1793 to 1815 were renowned for looting and one of the things they aimed for was the provisions, which indicates that the system which had been in operation previously had broken down.” (Macdonald 147)

In general, however, Macdonald surmises that the different navies did not display much difference “in the way” they “fed their crews.” She explains that “all were restricted by what was currently available and would keep in good condition for a long time, and with some regional variations, this came down to biscuit, salt or dried meat or fish, cereals, dried pulses and a little cheese and butter or oil with fresh food when in port.” (Macdonald 149)

In a rare slip Macdonald appears to conflate supply with preparation. Navies, like armies, reflect the societies that create them, and that reflection ought to include the way they cooked what they had. It would be hard to envision any cook from France boiling puddings or preparing pastry with suet, a word unknown in French. British tars drank rum; Americans Bourbon (at least by 1813) and the French, brandy. French vessels normally shipped “wine (always red)” but in the Dutch Navy “there was beer, in unlimited quantities until it ran out.” (Macdonald 144-45, 146)

6. British food at sea.

By the onset of the Georgian era, as Macdonald herself notes, “dried or salt fish had been dropped from the official naval diet” in Britain, at least in part because the sailors did not like it, but would have been needed in Catholic navies for fast and Lenten days, and it is hard to envision the British breakfasting on pickled herring like the Dutch.

Nonetheless if we are to look for pronounced national characteristics we must look to the food of the officers, not their men, because they have left the better record of what, precisely, they ate and how it was prepared. Like the ratings, the basis of their diet at sea was the preserved food supplied by the Victualling Board, but supplemented in any number of ways. Sometimes they ate what the men ate; boiled corned beef or salt pork, lobscouse, pease pudding, plum duff, sauerkraut (prevalent but not popular with British crews), sea pie.

Some of this food was not so different from what people ate at home, or on the streets of London, where vendors hawked both pease pudding and its lighter cousin, pea soup. The nickname of Liverpudlians, ‘scouser,’ quite obviously derives from a favorite landed dish, Lobscouse, a stew of meats and vegetables familiar to seamen in the age of sail and as varied in composition as the cooks who prepare it.

Puddings, both savory and sweet, were ubiquitous and relished in Georgian Britain, and naval practice reflected that fact. Cooks at sea were not yet using pudding basins, but the simple pudding cloth (described at bfia Number 2 in the lyrical ) had by now been replaced with the handier pudding bag.

Pudding bags are easy to make. Lillian Langseth-Christensen, who misnames them pudding cloths, explains with homely charm that they

“compared rather favorably with the long sleeve of a winter nightgown. The pudding cloth was a firmly seamed dense cloth measuring about seven- to nine-inches wide by fourteen- to eighteen-inches long. Splendid pudding clothes can be run up out of old tablecloths, preferably damask.” ( Mystic 212)

Some of her traditional American puddings, all of them sweet, use bread, milk and egg rather than the ancient combination of flour and fat.

Some of her traditional American puddings, all of them sweet, use bread, milk and egg rather than the ancient combination of flour and fat.

‘Duff’ referred not only to the dough used to make the pudding, but also to a finished more or less solid product; a roly-poly is as it sounds, a spiral of pastry laced with filling, which actually is easier to cook in the more primitive pudding cloth (a dishtowel will do). Both are foundational to British foodways. To make a rich duff for puddings, sift two measures of self-raising flour by volume into one of shredded suet, add a little salt and sprinkle with just enough water to make a soft dough; the amount of water required always seems to vary. Knead the duff into a ball; it helps to chill it for about half an hour, although that is not, strictly speaking, authentic to the eighteenth century.

Simple duff is much like the big dumplings that used to be served in slices with duck or goose at the long-lamented Vasata Czech restaurant in Manhattan. Do the same or serve it in the traditional manner, to accompany boiled beef or salted pork. To make Plum Duff, mix raisins or currents into the batter; the addition of sugar transforms Plum Duff into Spotted Dog.

Bacon mixed with raw or fried onion and either mushroom or apple is an excellent basis for a savory roly-poly; oysters or mussels with the onions are good too. For something sweet, spread your duff with jam or marmalade instead.

Traditional pease pudding still may be found in British homes (decent canned products are sold). It consists of seasoned soaked split peas, butter and egg, sometimes bacon and nothing more. Lobscouse, however, has as many incarnations as those who make it, essentially stew of simmered meat, vegetables and sometimes biscuit. Sea pie has its own essay in the lyrical.

7. Food for the toffs.

Officers enjoyed considerably more variety, both of foodstuffs and technique. Many captains, in common with Withnail’s Uncle Monty, kept a superb cellar that typically included Champagne and Sillery, “its non-sparkling ‘cousin,’” good Claret (Bordeaux) and fortified wines; Sherry, Port, Madeira. “Punches were popular, cold or warmed with a hot poker and often spiced; this may have been one of the uses for the stores of nutmegs, ginger, cloves and cinnamon.” (Macdonald 132) Officers bought coffee and teas too, and brought goats aboard for their milk.

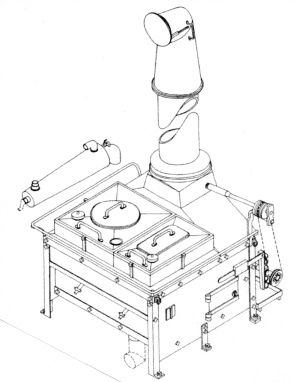

Most of the food that the ratings ate was boiled in the big ship’s stove manufactured by the naval suppliers Brodie or Lamb & Nicolson; smaller ovens for baking and roasting, however, also were fitted for the officers’ table and the ill. Officers’ cooks (many brought their own) therefore could bake bread and rolls, “not every day, perhaps, and not on a grand scale, but enough to keep the cabin, and the wardroom and the sickbay supplied.” (Macdonald 134)

Officers’ cooks (many brought their own) therefore could bake bread and rolls, “not every day, perhaps, and not on a grand scale, but enough to keep the cabin, and the wardroom and the sickbay supplied.” (Macdonald 134)

“They had butter and flour, so they could make pastry for tarts and pies; they also had eggs, dried fruit and sugar, so could make cakes; add milk to eggs and flour and you can make pancakes…. They had plenty of varied meats, and whether using the spit of the Brodie stove or the closed ovens of the Lamb & Nicolson, roasted meat means fat and juice for gravy and soups, as do bones…. ” (Macdonald 134)

At sea as on land, the Georgian age was not so bad a historical place for the better sort of Briton to eat.

Seaborne fresh meat, both butchered and live, included beef, hare, mutton, pork and venison; chickens, ducks, geese, partridges and turkeys. Officers shipped anchovies, bacon and ham; chutneys and pickles; pickled oysters; capers, horseradish and olives; mustard and curry powder. One of Nelson’s orders included forty-two pounds of Parmesan, Brunswick sausages, pickled tripe and salad oil. (Macdonald 128-30) There was chocolate, fruit and macaroons, jams and marmalade.

Carr’s began making ‘Captains’ Thins,’ precursor to the familiar Table water crackers, as “a refined version of ships’ biscuit” at the beginning of the nineteenth century; other cracker bakers, including Jacobs (the cream cracker people) also started out as suppliers to the captains of ships. (Macdonald 129)

Captains’ cooks prepared ducks roasted or boiled with peas and lettuce; fricassees of chicken or goose; corned beef with carrots and turnips; roast mutton, mutton broth and barley broth with bacon; greens with bacon; turtle and finfish of all kinds, including a seviche of tuna; various tarts; puddings; and pies of apple and gooseberry. (Lavery 616-21) The officers at sea on the East Indies Station ate a lot of curry. (Macdonald 135) Officers’ meals included selections of a variety of these and other dishes; diners would choose what they liked, help each other to the food and pass it around.

The largesse could have unintended consequences. Admirals and captains in particular did not lead the physically demanding life of ratings at sea. Some got fat, as their portraits attest; Sir Edward Pellew reported from the East Indies that he had become ‘fat as a pig.’ (Macdonald 132)

If any of this upends the notion that life in Nelson’s navy was characterized by cruelty and suffering, it must be disclosed that Admiralty regulations required each warship to carry at least one tormentor. It was the official as well as colloquial term for a large fork that the cook used to fish boiled meat from his cauldron from behind a screen--to ensure that he could not show favoritism to any segment of the crew, officers included. Nelson had issued a standing order that “all are to be equal in the point of victualling.” (Macdonald 102, 102n3)

Recipes for various puddings, corned beef , duck with lettuce and peas , Lobscouse , and sea pie appear in the practical. Recipes for fricassees appear at bfia Number 17 in our archive .

Editor’s note: Weevils do not ‘metamorphose’ into maggots. Weevils are little beetles and maggots are the larvae of flies.

Sources:

David Cordingly, Under the Black Flag: The Romance and Reality of Life Among the Pirates (New York 1995)

Lilian Langseth-Christensen, The Mystic Seaport Cookbook: 350 Years of New England Cooking (New York 1970)

Brian Lavery (ed.), Shipboard Life and Organisation, 1731-1815 (Aldershot, Hants 1998)

Janet Macdonald, Feeding Nelson’s Navy: The True Story of Food at Sea in the Georgian Era (London 2004)

Noel Mostert, The Line Upon a Wind: An Intimate History of the Last and Greatest War Fought at Sea Under Sail, 1793-1815 (London 2007)

N. A. M. Rodger, The Wooden World: An Anatomy of the Georgian Navy (Annapolis 1986)

The Command of the Ocean: A Naval History of Britain, 1649-1815 (London 2004)