Complexity, contradiction & horse trading: An Irish journey both historical & familial.

1. Lost and found.

An intriguing artifact on any number of levels, the commonplace book kept by Mrs. Cannon straddles any number of worlds: Rebellious and imperial; catholic and protestant; Irish, French, New World and Indian; medieval and modern. It therefore is all the more surprising that the manuscript with accompanying text provided by Marjorie Quarton has received no notice from historians, cookbook and cookery writers or anybody else.

In his book on Irish country cooking, Colman Andrews for one cites Quarton’s memoir but not the commonplace book and bungles his quotations. In their otherwise encyclopedic Cookbook Library Anne Willan and Mark Cherniavsky include a section on commonplace books but overlook Quarton and Cannon altogether.

Perhaps, however, the neglect of the Cannon manuscript is not so surprising given the state of historiography involving Irish foodways. In contrast to her commonplace book, virtually all of it is sloppy, sentimental, chauvinistic, sectarian, nationalistic or otherwise bad.

An underutilized resource and an underappreciated author.

2. Irish catholics.

Quarton is descended from the Cannons along with another ancient Irish family, and her lineage embodies the cultural, ethnic, political and religious intersections of Irish history. The record of an ancestor first appears in Ireland during 1311 and the Cannons prospered. “Arms were conferred on the family in 1614;” by then the family owned land not only in Ireland but also in Norfolk and Pembrokeshire. ( Commonplace xii)

The Cannons, however, or most of them anyway, had remained catholic. A direct ancestor of Quarton, Alexander Cannon, fought for the Jacobite army in Scotland and rose to the rank of Major General commanding a motley force of some Irish and mostly Scots troops, all of them “ill fed, ill armed and ill disciplined.” Following their defeat, he and they fled to France where they and exiles like them “formed the nucleus of the first ‘Irish Brigade.’” ( Commonplace xii, xiv, 129)

3. Irish protestants.

At some point after the Boyne, Cannons converted to the Church of Ireland, “not entirely for religious reasons” as Quarton sardonically notes. That should be no surprise. She explains that both before and after the reformation, Catholic Cannons had “worked for and with the English administration” in Ireland for centuries and likely shared no desire to lose their considerable stature and influence after imposition of the Penal Laws.

At the battle of Plassey, which extinguished the French presence in India during 1757, British regiments included the Royal Dublin Fusiliers, “while the French army attacking the British included the Irish Brigade, of which Alexander Cannon had been a member.” ( Commonplace 129)

Following his flight to France, any record of General Cannon vanishes--Quarton thinks he died there--but a son, Patrick, appears as “gentleman of the City of Dublin” where he owned substantial property although in fact he lived in Dun Laoghaire. Patrick of course “would have been marked Catholic by his name,” at birth anyway, but must have converted to protestantism because, as Quarton quips, “his son was called George, which is as far as possible from Patrick” as an Irish marker of religion and allegiance go. ( Commonplace xiv, 68)

It was Patrick who married Mary, in 1700; she began her commonplace book the following year. Their son George would take a Huguenot bride and their descendants served as officers in the Royal Navy and British Army, or practiced medicine, or both. One of them, Aeneas, served as a surgeon under Wellington in the Peninsula and at the climactic Battle of Toulouse before postings to Jamaica and Canada. He retired to Cheltenham where he continued to practice medicine; other Cannons remained at Dun Laoghaire until 1900.

4. Anglo-Irish.

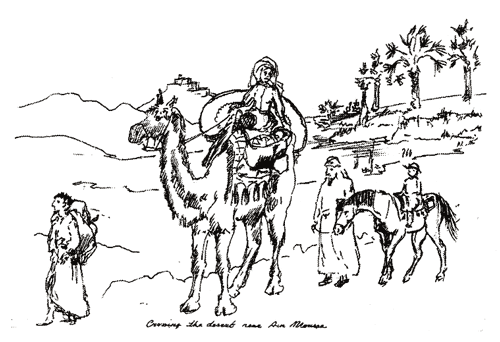

Quarton’s grandfather was an army chaplain posted to India just in time for the Mutiny. The family survived the slaughter in the relatively secure environs of Pondicherry, which had been the immediate prize at Plassey. When, however, her husband was transferred to the dangerous Punjab (it remains so), his wife returned to England with their three babies, crossing the Sinai by camel along the way. ( Commonplace 129-30)

Great grandmother crossing the Sinai with infants.

On her father’s side Quarton is a Smithwick, her mother an English Cannon who “lived in Ireland for fifty years but never wanted to.” Quarton “dislike[s] being classified as Anglo-Irish, but there seems to be no escape,” especially given her colorful description of a most eccentric upbringing. Inescapably Anglo-Irish as they are, except in comparison to the Cannons the Smithwicks are no interlopers to Ireland. The family arrived there during the fifteenth century and, among other things, founded the brewery that abides today. ( Breakfast 10)

One of her Smithwick uncles died in the Zulu wars, another became an admiral; her grandfather Chancellor of St. Patrick’s Cathedral in Dublin. Quarton’s father suffered severe wounds as an officer in the trenches on the Western Front with the Royal Dublin Fusiliers. (“Diary”) The loss of life there was horrific. Only four of the regiment’s officers survived the war; her father “died at eighty from a piece of wandering shrapnel which had been in his stomach for forty years, causing him untold pain.” ( Oil and Water 144)

So Quarton is Protestant, but that does not pigeonhole the family in the facile way of Irish Americans. Her grandmother for one, friend of Maud Gonne and Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington, was a suffragette, Nationalist and Republican notwithstanding all that ancestral devotion to England, Union and Empire. ( Breakfast 9, 10)

5. Straight out of Troubles.

As if this were not interesting enough, Quarton herself is a fascinating figure. She was born an only child in rural Tipperary to smallholders who neglected her. She seldom left the farm as a child, notes that the vision of her generation “was blinkered by lack of communication and censorship,” and has for much of her life felt lonely but found solace with animals. Quarton “cannot remember a time when horses meant nothing to me.” ( Commonplace 104-05; Breakfast 1)

Quarton does remember the first time she mounted a horse, a Clydesdale of all breeds, by sneaking into the forbidden stables aged four “with the rashness born of ignorance which is sometimes mistaken for courage.” ( Breakfast 1) Then again, in a striking insight equally applicable to skiing, she recounts that as a pre-teenaged rider “I wasn’t frightened of falling, so I seldom fell.” ( Breakfast 16)

War games with her old pony Pippin, engagements resembling the madcap portraits that J. G. Farrell depicts in Troubles , were a treasured pastime:

“One of them required my father’s help. I was the Flower of the French Cavalry or a Death’s Head Hussar, according to which war we were fighting; he was unshaken infantry. He knelt on one knee, aimed a shooting stick, and Pippin and I charged him. Pippin would sheer off at the last second and I, more often than not, fell off. I enjoyed these simple war games enormously, and began to improve on them. I invented one in which I cut off the heads of thistles with a sword (a real one) while galloping bareback across a field.”

“This activity,” Quarton explains with a certain understatement, “was discovered and stopped, but not before I’d fallen off… usually on my head…. ”

In response her parents decided she should take precautions. “After that,” Quarton recounts,

“my father taught me to fall on my feet like a cat. I started my falling-off lessons in the haybarn, tumbling off the patient Pippin backwards, forwards and sideways. Then I graduated to jumping off at every speed up to a gallup. It was great fun…. ” ( Breakfast 15)

Quarton was eight years old.

In addition to their obsession with safety, her parents “were great believers in hard work to form character.” At an early age, Quarton “could drive most horse-drawn implements,” including the tumbling rake, “not an implement to daydream behind” because if improperly handled could “impale the driver” or maim the horse. Out of prudence Quarton was not allowed to drive a tumbling rake until the age of twelve; Anglo-Irish indeed. ( Breakfast 28-29)

6. Hard times.

At the outset of her memoir Quarton admits with, it appears, intersecting strands of veracity and irony, that her background and childhood were “of the kind called privileged.” The family in fact became impoverished after independence by De Valera’s economic fantasies and obsession with autarky. At one point her mother sewed Quarton a dress from her bedroom curtains.

While many of their peers had no choice but to sell their properties to the Land Commission, the Quartons held on to their farm, just, thanks to her father’s British Army pension. ( Breakfast 35, 10) They had been prescient enough to take the right side in the civil war; the farm had been a safe house for Michael Collins several times.

Our precocious rider therefore made do, improvising tack from “odds and ends of trap harness,” rotting lampwick, twine and wire. ( Breakfast 19)

She had no formal, and nearly no informal, schooling until sent away to board near Dublin on VE Day aged fourteen and a half in part “to,” she ruefully recalls, “detach me from my first boyfriend.” It was her first real contact with girls her own age.

The school itself “was located in an enormous and viciously cold Palladian mansion of great historic interest.” The classrooms had Adam mantelpieces and other elegant furnishings. Quarton endured an “intensely miserable” two-and-a-half years there. ( Breakfast 38, 37)

7. Off to the races and on to the horses.

At least she got into town one day chaperoned by the housekeeper, “an attractive girl only a few years older than we were, and equally impatient of authority.” Instead of shopping as the school expected they went to the races in Phoenix Park. Quarton’s horse, “hideously named ‘The Bug,’” came in at seven to one. ( Breakfast 40)

On her return to Tipperary, Quarton would become a hardworking horse dealer at the age of seventeen. ( Breakfast vii, 6, 12, 19) Despite all the hardship, however, she displays not a trace of bitterness but rather a generous heart and mind. Nearly every other Anglo-Irish memoir represents “the record of a dying way of life, and the urgency to document the fall of the father’s world often subsumes the desire to tell a personal story.” Breakfast the Night Before is, according to Elizabeth Grubgeld, a “rare exception to this pattern.” (Grubgeld xiii, xiii n3) in it Quarton chronicles an eccentric and eventful life well lived instead of mourning the loss of wealth and stature.

8. Irish eccentricities.

The memoir, Breakfast the Night Before: Recollections of an Irish Horse Dealer , is extremely well written and loaded with lovely anecdotes and insightful asides. In her time, she recounts, Irish wholesalers shipped geese to Liverpool for marching as far as Newcastle,

“…. But their feet wouldn’t stand up to so much roadwork. Accordingly, at the port, they were driven first through soft tar, then through sand. After this treatment, they were as good as shod. No wonder Irish geese were more renowned for muscle than fat.” ( Breakfast 6-7)

A Captain Finch brought his terrier, “well named Bouncer,” with him to church “and Bouncer sat in the pew where his violent scratching, the rattling of his chain and his master’s furious commands to be quiet often drowned the rector’s words.” “The Captain,” Quarton notes with a certain understatement, “had various eccentricities…. ” ( Breakfast 32)

Another Ascendancy scion summoned his family to dinner with a hunting horn; a third landowner found it preferable to use a window instead of the door because he considered it “easier to open and shut. His visitors,” however, “were allowed to use the door, if they were tactless enough to insist.” ( Breakfast 84)

Racing enthusiasts had a fondness for naming daughters after winning horses, even if the possible names might include Melton, Nicandra, Paradox, Red Ruin and Xaintrailles. ( Oil and Water 263; Breakfast 84)

When buying cattle, “you have to be able to reckon quickly in the auction ring. To use a calculator brands you as a wimp or, worse, an agricultural advisor.” She would know; Quarton first bought bullocks in place of her ailing father on a school break at the age of sixteen. ( Breakfast 39, 42)

Point-to-point racing in Ireland

9. Perils of the point-to point…

Point-to-points were reckless races across country. Quarton witnessed her first at the age of five, holding her nanny’s hand “and running, with her in order, she said, to see someone killed.” Quarton herself entered her first point-to-point when she was nineteen.

Irish riders were, unlike the English, willing to leap the highest hedge, but also like their English counterparts, feared leaping fences. During one of Quarton’s point-to-points a fearless rider with a ferocious horse allayed their concern. “’I’ll smash the top rail for you,’ said Mick, ‘This bugger has a heart bigger than a duck.’ He duly smashed it.” ( Breakfast 96)

Over the years she has

“seen a man thrown off his horse by the rider beside him who simply caught him by the foot and lifted it over the saddle. Nobody was hurt and the culprit was disqualified, but the action enabled a horse to win which he had backed to beat his own.” ( Breakfast 135)

10. …the hunt…

Foxhunting was so associated with the Anglo-Irish, and in particular large landlords, that it became a target of the Land League during the 1880s. Leaguers not only disrupted hunts by throwing stones, brandishing ashplants and invading meet terrain. Sometimes protesters killed the beagles. They also organized shambolic “peoples’ hunts” chasing hares and rabbits in shabby costume with mongrel dogs and mock cheers to parody the actual things. (Curtis)

Hunting as practiced by Quarton’s contemporaries resembled the Fenian parody more than the English paradigm. As she recounts, the Galway, Limerick and North Tipperary Hunts were “notably lacking in spit and polish.” Not everyone wore the ‘required’ red coat, jodphurs and boots; some wore ragged sweaters, shorts and wellies.

The contrast was not only sartorial. Quarton remembers “a group of us passing a horn from hand to hand, each trying in turn and in vain to extract the right sort of noise from it. Our inefficiency can be judged,” she confesses, “from the remark of a would-be huntsman in cover, ‘Jesus lads, we’re ruined now, they’ve found a fox.’” They did not “hunt hares except occasionally by mistake.” ( Breakfast 54)

Mishaps elicited responses that, outside Ireland, would appear decidedly odd. A doctor and veterinarian were attending one of Quarton’s less disorganized hunts when a rider took a bad fall after the horse rammed a post strung with barbed wire. Their choreographed response was immediate.

“The doctor pulled a first-aid tin out of his pocket and set to work to stitch up the staked horse. The vet rushed to help the young woman (who was very pretty) and lent her his horse to ride home on.” ( Breakfast 94-95)

Some equally unfortunate horses became alcoholics because their owners gave them too much stout; subsequent purchasers needed to push them through painful detox. ( Breakfast 27) Another unfortunate horse had the longest mane Quarton ever had seen. Its owner therefore knotted together two locks to form each stirrup. ( Breakfast 92)

Chaos often preceded the hunt itself. Much drinking might render riders reversed. Outside a Tipperary public house, she witnessed

“a gentleman who normally knew better… mount his horse facing the tail. ‘Something wrong,’ he muttered, ‘no ears.’” ( Quarton 55)

It also was a difficult business to serve on the hunt committee. After one exasperating session that Quarton attended, the committee was so fractious that its sole minute duly read:

“The committee’s decision was not to decide what to decide until a decision had been reached.”

Once the committee did decide how to proceed, hunters themselves threatened to scupper the hunt because they tended to sell their horses on the way to the meet. On one occasion a huntsman arrived ‘in full hunting regalia, riding a bicycle.” When asked why, he snapped “I couldn’t sell it.” ( Breakfast 92)

11… and of the hunt ball.

The balls thrown to finance the hunt presented other dangers. At one of them, held in “an ice-cold upper room of the Courthouse,… a lady put her foot through a rotten floorboard, and the hole was still there the following year.” ( Breakfast 99)

A ground floor ball could pose perils of its own. At one of them the windows opened onto a garden. Drunks shoved them open from outside to demand entry at half the nominal cost when they considered the ball half over. When Quarton’s waltzing partner “courteous as always, bent down to explain why this was not possible” he was “immediately seized him by the collar and dragged half way through the window.” As his coat split, Quarton and the hunt secretary “caught hold of a leg apiece and dragged the poor gentleman to safety.” “After that,” she drily notes, “the widows were kept bolted.” ( Breakfast 98)

12. Evolving Irish foodways.

The receipts in the commonplace book, for that is what they then were called, were of course compiled over time, Quarton believes from 1701 through 1707, except perhaps for the baking. As Quarton notes in one of the engaging ‘interludes’ with which she frames them, the instructions for baked goods “have a touch of modernity lacking in the others.” Everything baked appears in a discrete section near the end of the manuscript Quarton figures it resulted from a visit to relatives in Yorkshire. Mrs. Cannon, or someone else in her family or service, may have acquired a wall oven there at a time when Irish cooks still baked with the bastable, an iron pot fitted with a fenced lid for holding embers from the fire beneath.

The rest of the recipes rub along at random: “In the original we jump from wine to fish to boot polish and back again.” ( Commonplace 68) So if the baked goods look modern, the rest of the manuscript in its disregard for classification does not.

13. Some things old....

A number of Mrs. Cannon’s recipes appear as premodern as her format; some of them have roots that go deep indeed. Some of the recipes, like a pork pudding that incorporates currants, raisins, clove, mace, rosewater and sugar mix savory and sweet in the medieval through sixteenth century manner; the practice was beginning to fade when she compiled her kitchen manuscript.

Pottage, a humble sort of savory porridge, was the staple fare for all strata of English society throughout the medieval centuries. Anything might find itself simmering in the pot, but the base always was some kind of grain, meal or bread, or any combination of them. In England, all manner of green herbs in great quantity was omnipresent, along with ‘sweet’ spice. Aromatics, along with cheap fish or meat, root and other vegetables also could be thrown into the pot. (Perkins 44-46)

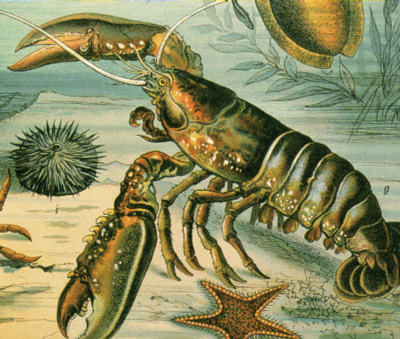

The dish that Mrs. Cannon or more probably her cook cooked may appear to the modern eye as an elegant outlier to the pottage world; she used lobster. That view, however, would be anachronistic. Lobster then was not the luxury it has become, but rather a cheap and often unwelcome protein for the poor. In eighteenth century Boston, the contracts of indentured servants typically limited the number of times a week their masters could foist the shellfish onto their plates.

Upon inspection the pottage Mrs. Cannon recorded is entirely typical of the medieval paradigm or, in the parlance of our time, authentic. It has the traditional base (in her case bread); the green herbs (mint and spinach); traditional spice (clove and mace); and cheap lobster.

Then again, however economical a lobster pottage could have been, the Cannon recipe looks like she had made it fancy enough for guests. Mrs. Cannon does not spare the butter and cream; specifies serving her pottage with forcemeat balls, and its presentation was important to her:

“When it is enough [that is, done], Garnish ye Dishe with ye Claws of ye Lobsters and Serve it.” ( Commonplace 11)

However old fashioned, and it would have been dinosauric by 1700, the ingredients in the pottage indicate that the dish was meant for display. Its expensive additions and careful presentation represent vehicles meant to demonstrate the prosperity of her family.

14. Markers of gentle stature.

The large number of preparations for fish in itself indicates that the Cannons were prosperous; those of lesser means in Ireland never have eaten much from sea, stream or lake. The commonplace book includes recipes for an array of fresh, salt and shellfish including bass, carp, mullet, pike, trout, whiting, cod, eel, turbot (“Turbitt”), lobster and oysters.

A further marker of prosperity: The poor had begun to subsist on potatoes during the eighteenth century. No potato, however, appears in any of Mary Cannon’s recipes.

What does appear is a selection of recipes pretty much indistinguishable from what any contemporary, if a bit culinarily conservative, member of the English gentry might instruct her cook to prepare. No sectarian divide marked the foodways of prosperous Ireland. And if the commonplace book includes no extravagant or sumptuous recipes, it includes no frugal ones set at the level of basic subsistence either.

15. Imperial continuities.

The recipe “To Make Alamode Beef” encapsulates the continuity of eighteenth century British Atlantic foodways not only across a religious divide but also across space and time. Mrs. Cannon’s recipe is very nearly the same as the one Charles Carter published in London during 1730 and the one Amelia Simmons published at Hartford in 1796. Hers in turn was plagiarized from earlier English sources.

It is a good dish, essentially a pot roast. The beef is marinated in vinegar, a nice touch absent from the later recipes, then larded with bacon stewed in red wine, stock and onion; seasoned with allspice (“Jamaica Peper”), clove, mace, pepper and thyme; and thickened with bread rather than flour. It may be served cold or hot; if hot, Mrs. Cannon recommends a sauce made with the cooking liquid, brown butter, artichoke bottoms, mushrooms and “Pallets,” which Quarton believes are “pieces of pork chine” but more likely are ox palates.

Other attractive dishes in the commonplace book include “Scotch Colopes” (collops), thin slices of veal simply, quickly fried but sauced with a sophisticated combination of “Broth and Gravey,” forcemeat balls, mushrooms, onion, oysters, more of those Pallets and sweetbreads.

In contrast “A Savoury Sauce for Collared Breast of Veale” is simplicity itself:

“Boyl ye bones of ye Veale and add to them one Nutmegg and one Anchovie. Beat it up with a lump of Butter and some Oysters if in Season.”

Any kind of meat bones would do, and the sauce is particularly good for steaks or chops as well. The modern cook might add cayenne or hot sauce and Worcestershire.

Stewed mutton neck is similarly simple and equally worthy of revival:

“Cutt it into Stakes, cover it with water and let it Boyl. Then scum it and putt in a little Peper and Salt, a Bunble of sweet Herbs, pickled oysters, a half Anchovey and a few Capers.

Stew all these together about two Houres, then lay Sippets in ye Dishe and serve it.”

Sippets are slices of toast; otherwise the recipe is so clearly rendered that it requires no translation for the twenty-first century.

If cooked in the United States absent the services of a halal butcher the mutton will need to be lamb; fresh or even shucked oysters from the refrigerator case are fine.

16. Some quasicompetent Irish cooks.

Cooking and eating could be an adventure in Quarton’s own time. The family always had a cook until in straitened times it did not. “Not necessarily a good cook,” Quarton recalls, “some of them were appalling, but a person capable of putting some kind of meal on the table at stated intervals.” One of them sieved flour for soda bread through her stockings. (Quarton 63)

The loss of the last cook, however slovenly her skills, posed a pressing problem because none of the family had much familiarity with the kitchen. Quarton “was sixteen when the last one departed. There followed an interval of hunger and indigestion.” Her mother “could make only cakes:” Quarton herself only porridge and scrambled eggs. Her father had a little more range. He “could make soup and curry, and on the cook’s night out, he did this,” apparently a difficult endeavor:

“For the purpose of cooking, he first put on his hat…. As a rule, it was a sign he was going to do something fairly dramatic.” ( Breakfast 112)

One year at Christmas Quarton’s mother bought a turkey she thought was stuffed: “Alas, it was nature’s own stuffing.” They reverted to soup, curry and cake for dinner. At some point she found her “father (wearing his hat) disemboweling the turkey over the sink with the help of a toasting fork. He hacked the bird to pieces” and the family ate it, “first baked and later curried, for days.” ( Breakfast 113)

Dinners at the hunt balls were as bizarre as everything else about them. At one ball the bewildered servants set gravy on the table with the dessert; Quarton for one doused her ice cream with it. Her elderly companions followed suit and “either didn’t notice or pretended not to.” ( Breakfast 99)

Soup once was set out by mistake for coffee. When she tried to warn her quarrelsome partner of the switch he replied “Rubbish” and “put a spoonful of sugar in his mug, stirred it and took a generous swallow.” Quarton “managed not to gloat too much.” The host of another hunt ball, frigid because he allowed his fires to die, offered the guests a nightcap. It turned out to be “tepid Ovaltine and stale cream crackers.” ( Breakfast 99-100, 101)

Dining out on the road or railroad might be worse. “The railways were geared for horses in the fifties,” as astonishing as that sounds, but smoke from steam locomotives coated everything, so “travelling by rail with a horse was a hungry business. One carried sandwiches (ham and coaldust) or chocolate (fruit, nut and coaldust).”

Some provincial hotels were worse again. A dining room in one Tipperary town was unmatchably vile. The “washing-up-water soup” preceded “boiled whatever-it-was” (she suspected dog) with “raw potatoes, liquid grey cabbage and melting, onion-flavoured ice cream.” The tea tasted like “liquid brown boot polish.” ( Breakfast 69, 70, 103)

A domestic kitchen could pose different problems. An “elderly bachelor” acquaintance of Quarton’s from the horse fairs attempted one evening to cook them supper. He put something on the stove. “It turned out to be a tin of herrings in tomato sauce. The tin, not being punctured, exploded, liberally daubing the ceiling with tomato sauce, while herrings flew in all directions.” When Quarton arrived home, her cat ate several of them from the inside of her hood. ( Breakfast 202, 203)

Quarton’s daughter and family live on the ancestral farm now; Quarton doubts her daughter “plans to use Mary Cannon’s recipes,” but why not? ( Commonplace 157) Quarton and her parents might have put the little commonplace book to good use in their days of soup, curry and cakes.

Sources:

L. P. Curtis, Jr., “Stopping the Hunt, 1881-1882: An Aspect of the Irish Land War,” C. H. E. Philbin (ed.), Nationalism and Popular Protest in Ireland (Cambridge 1987) 353-86

Elizabeth Grubgeld, Anglo-American Autobiography: Class, Gender and the Forms of Narrative (Syracuse 2004)

Blake Perkins, “An Enquiry into the Derivation of Chowder,” Petits Propos Culinaires no. 109 (September 2017) 32-67

Marjorie Quarton, “An Irishwoman’s Diary on a strange meeting near Ypres in 1915,” Irish Times (1 August 2016)

Breakfast the Night Before: Recollections of an Irish Horse Dealer (Dublin 2000)

Mary Cannon’s Commonplace Book: An Irish kitchen in the 1700s (Dublin 2010)

Oil and Water: Molly Keane and her World (Dublin? 2013)