An Appreciation of inconsistency

1. Luddites in a good way.

We previously have profiled the irresistibly eccentric Homefield operation in Sturbridge, Massachusetts. We should organize a pagan thanksgiving service because, so far, the nanobrewery and homely kitchen have survived the plague. Their mission is optimistically Luddite, a return to preindustrial scale and ethics.

The mission requires local sources for everything they need to brew their beer and cook their food. They also support their suppliers by scheduling farmers’, cooks’ and bakers’ markets onsite within their atmospheric subterranean operation. All that devotion to surrounding sources and, yes, community requires a business philosophy at once counterintuitive and practical.

Homefield logo hat.

Homefield logo hat.

2. The fear of flexibility rebuffed.

During the nineteenth century Emerson fired his famous fusillade condemning “foolish consistency… ” as “the hobgoblin of little minds.” “With consistency,” he warns,

“a great soul has simply nothing to do…. Speak what you think now in hard words, and to-morrow speak what to-morrow thinks in hard words again, although it contradict every thing you said today. -- ‘Ah, so you shall be sure to be misunderstood.’ -- Is it so bad then, to be misunderstood?... To be great is to be misunderstood.”

A similar sentiment has been broadly attributed to Keynes and others, although an absence of written evidence indicates that the aphorism, “When the facts change, I change my mind: What do you do?” or something similar, may be apocryphal, which is a bit of a disappointment.

Or perhaps not, at least not quite; a number of authors attribute the phrase to Paul Samuelson. During an appearance on “Meet the Press” late in 1970, Samuelson explained why his recent attitude toward inflation (undesirable) contradicted an earlier view (beneficial to growth), he did quip that “when events change, I change my mind. What do you do?”

The problem with giving credit to Samuelson arises from statements made by Samuelson himself. In a 1978 interview with the Wall Street Journal he

“recalled that John Maynard Keynes once was challenged for altering his position on some economic issue. ‘When my information changes,’ he remembered that Keynes had said, ‘I change my mind. What do you do?’” (“quoteinvestigator”)

Samuelson, a Nobel laureate, attributed the retort to Keynes again twice in 1983, the year of the ‘Keynes Centenary,’ and then in The New Yorker during 1996. (“quoteinvestigator;” Cassidy) If Samuelson had not heard the aphorism before he used it then it is unlikely he would have given someone else credit, even a figure he revered as much as Keynes, although the possibility remains that Samuelson was mistaken about the source of the comment.

Joan Robinson in 1973.

Joan Robinson in 1973.

That, however, appears an unlikely error by the fastidious Samuelson and in fact an earlier if indirect source does exist. According to G. C. Harcourt, Joan Robinson, like Keynes a Cambridge economist, and like Samuelson an unabashed admirer, liked to link a version of the phrase to Keynes. “Her favourite saying of Keynes was,” he recounts in a number of places,

“‘If someone persuades me that I’m wrong, I change my mind. What do you do?’ Her own life was a splendid example of this attitude.” (emphasis in original) (Harcourt, “Obituary;” see “Piero Sraffa”)

Robinson is a compelling figure in her own right, a lifelong socialist and influential thinker who enjoyed a distinguished career not only at Cambridge but also as a visiting scholar at other elite universities and colleges. Her attraction to economics was hardly based on a love of theory in general or mathematics in particular. Instead,

“Joan Robinson read economics at Cambrige because she wanted to know why poverty and unemployment existed. Her time in India in the 1920s [Robinson was born in 1903] deepened her hatred of poverty and injustice.” (Harcourt, “Joan Robinson”)

Harcourt himself is a distinguished economist who in turn knew and admired Robinson from their years together teaching at Cambridge. While he provides no independent attribution for the aphorism, it is most unlikely that he did not hear her claim it for Keynes.

Finally for now Keynes himself indirectly raised the inference that he first said it by raising the issue of his inconsistency in a 1933 letter to The Economist. In connection with his (then; the position would change) advocacy of the gold standard, Keynes wrote that

“since there are people who deem it creditable if one does not change one’s mind, I should like to get what kudos I can from not having done so on this occasion.” (“quoteinvestigator;” Economist )

Keynes was proud of his penchant for breaking with his own prior pronouncements, a trait his antagonists found infuriating. Writing for a popular audience in 1945, an admiring Noel Busch explains that

“Keynes is always ready to contradict not only his colleagues but also himself whenever circumstances make this seem appropriate. So far from feeling guilty about such reversals of position, he utilizes them as pretexts for rebukes to the less nimble-minded.” (“quoteinvestigator;” Busch)

John Maynard Keynes

John Maynard Keynes

None of this amounts to conclusive proof and most of it amounts to hearsay but it is strong hearsay and while other sources disagree, on balance it would appear safe to draw the inference that Keynes did coin the phrase.

New York mayor Ed Koch admitted to much the same thing as Keynes. When asked how he could explain contradicting an earlier position he reportedly replied, without missing a beat, “I was an idiot then.” Apocryphal perhaps, but the retort sounds like Koch and encapsulates his pugnacious and irreverent style.

3. The concept of inconsistency celebrated some more.

Reviewers of Zadie Smith cannot resist a line from the preface of Changing My Mind , her collection of essays from 2010. She is neither pugnacious nor irreverent but rather reflective whether addressing classic literature or contemporary issues. As the “confessional” title of the collection indicates, Smith is another celebrant of flexibility in all things: “Ideological inconsistency is, for me, practically an article of faith.” ( Changing My Mind xi)

In an ungenerous review of the essays, Pankaj Mishra cites the passage with some disdain before proceeding with the sort of self-righteous, sour postcolonial critique that remains much in vogue a decade later.

In his review of Intimations , the set of Smith essays that has just appeared, John Williams cites the sentence with longing for a lost era of intellectual dialogue. It provokes a succinct and supple meditation on our times from Williams, unlike Mishra an unabashed admirer of Smith:

“It’s never been a boom time for wisdom--almost by definition; if it were more common, it wouldn’t be valued so highly--but this is an especially arid era for it. We’re in the Age of Certainty, at least in the bellowing of its various constituents…. ‘polemic’ is too generous a word for the dominant cultural tone.

All of which makes Smith feel especially out of time.”

We have traveled far from the enlightenment when Hume could insist without irony or anxiety that “truth springs from argument among friends.” Not even friends let alone the unacquainted dare argue anymore.

Williams goes on to describe Smith’s “trademark levelheadedness” that, however, never “avoids moral stances.” It takes a certain cultural courage to approach the loaded term “privilege,” which Williams properly considers “the word of this century so far” with the nuance Smith displays:

“She notes her own advantages; parses the stubbornness of inequality; and outlines the explanatory (and experiential) limitations of privilege, including its ultimate inability to shield anyone from suffering, sometimes to the point of suicide. In Zadie Smith’s universe--meaning, for my money, the one we’re all living in--complexity is king.”

Zadie Smith

Smith is an acute observer of New York and New Yorkers, of the peculiar gifts the city gives to those who choose to accept them. She refers to the White Horse Tavern, not the tourist trap on Hudson whose liquor license has been pulled for the refusal to enforce social distancing but the boisterous dive down on Bridge below Wall Street. There, and Smith is right, “the 11 a.m. drunks” are “greeted with fond familiarity.” ( Intimations 39)

An older acquaintance’s “tall, elegant body has become a little more hunched over” and tends “to list rightwards these days, like a willow.” She ‘barks’ “ambivalent declamations” at Smith,

“about the weather or a piece of prose, or some new outrage committed by the leader of a country which, in [her] mind, only theoretically includes her own city.” ( Intimations 50)

In a triumph of affection over experience the elegant woman assures everyone that her vicious little dog will not bite.

Smith catches the rhythm of the city’s speech in her description of an endearing, enduring phenomenon about a certain segment of New Yorkers more generally:

“Like so many downtown women, she hasn’t gotten older in the traditional feminine way, that is, by becoming in some manner less visible or quieter, less apparently confident, less abreast of what just opened at BAM or the Joyce, or what overhyped musical just shit-the-bed on Broadway…. And if you ask her in a concerned tone ‘what she’s doing for the holidays’… you’ll find she’s just booked a solo walking tour up in the Catskills, or she’s meeting with her radical women’s group to discuss the writings of Anais Nin.”

These disclosures emerge in a voice any New Yorker not native to the city will recognize:

“She has a broad New York accent the precise borough and decade of which I can’t identify, except to tell you few people in Manhattan seem to have this accent anymore.” ( Intimations 46)

“There is,” Smith concludes, “an ideal, rent-controlled city dweller who appears to experience no self-pity…. ” ( Intimations 49)

That calm, assured power of observation jostles with (a little) self doubt. Smith feels guilt about fleeing New York and the willowy woman as the plague progresses but goes anyway: Although Smith has no “survival instinct”--she fears she would accept “the passive death that occurs if you stay under the bed as they march up the stairs, or lie down in the cornfield as the plane fitted with machine guns heads your way”--she has “a homing instinct and so in [her] passive way” accepts an invitation to stay in the country. ( Intimations 44)

“I can,” she confesses, “be very dumb about things that seem to others straightforward and obvious.” ( Intimations 67) Who has not felt that way? But who, apparently in common with Smith, has not sometimes harbored the sneaking, self-serving suspicion that the dumbness is superior, a willingness to find in something the nuance that others would rather disregard?

On another baleful flashword of the times, Williams notes that Smith “writes elliptically of identity as an ‘area of interest,’” nothing more, not a compass or lodestar; out of time indeed. None of this will endear either of them to the braying Agents of Certainty who refuse to notice its actual absence from critical thought and civil discourse.

4. Necessity, invention and all that in Maryland.

And so to the intersection of facts and foodways. Reporting in The New York Times on the storied if obscure subject of ‘Maryland Rye’ and its revival during 2019, Clay Risen and other sources note that Maryland rye had been celebrated throughout the United States and across western Europe during the nineteenth century. Unlike a number of other iconic foodsuffs including for example macaroni & cheese, Maryland rye has not attracted much attention in print.

The cause for the collapse of the Maryland whiskey industry and its idiom after Prohibition, however, is a mystery. “How,” Risen asks, “could a product so widely appreciated disappear so completely?”

Despite its singular status in some circles, nobody is quite sure what it was. In that miniscule respect ours remains an Age of Uncertainty. That, Risen believes, is not a bad thing. “The fuzziness around the definition of Maryland rye,” Risen muses, “may be exactly the point.” Why?

“Before the social media, before Prohibition, before the Pure Food and Drug Act and the modernization of distilling,” he explains, “inconsistency was a given. Maybe it was even prized.”

Maryland rye may have varied in style, but the variation appears to have occurred within a discernable band;

“many distillers and historians today agree that Maryland rye did have a different flavor profile--sweeter than the rye made farther west, with less spice and a supple, perhaps buttery palate.”

One revivalist distiller believes the sweet notes resulted from blending the rye with corn, but others disagree. Before Prohibition, Risen maintains, distillers or at least the ones producing Maryland rye did not record their recipes so nobody can be certain what kind of mash bill many of them used.

That is not quite right. At least some distillers did record their recipes. Henry M. Wright, Jr., whose “father probably sold more rye than anybody in history,” owned a liquor brokerage that distributed a number of Maryland ryes, has found “a lot of the old formulas from the old brands, some that are handwritten.” At the time of an interview in 2015 (four years before Risen wrote his article) Wright had not divulged any of them. He planned to start his own distillery to produce “real Maryland rye” and therefore may not have wanted to share them with his potential competition. (Jensen)

Ned Wight, another revivalist whose ancestors “ran one of the largest distilleries in Maryland, says his family’s distillery had no use for corn.”

“Generally,” he insists, “old Maryland ryes were made with rye and malted barley,” which would, however, have been more expensive than corn. To account for the sweet flavor, Wight speculates that Maryland distillers used brewers’ yeast to ferment their grain which, he maintains, “produces lighter, more floral notes than a traditional distiller’s yeast.”

Another revivalist, Todd Leopold, uses corn and brewers’ yeast, then a second fermentation using wild airborne yeast, which would make inconsistency inevitable except that he then distills his whiskey a third time. According to him and Risen, the third distillation expunges the spicy notes that otherwise result from the use of rye. (Risen) It would not necessarily be obvious why the elimination of complexity would be desirable but apparently it was, or is anyway to Leopold and his customers.

Risen notes that laboratory yeast had not appeared before the twentieth century, so distillers “developed their yeast cultures from whatever happened to be floating in the air nearby.” If so, that may have accounted for inconsistency except for the third distillation unless some producers omitted it. Risen himself does not address any variables that may have inhered from the use of barley or a three chambered still.

Another explanation may lie with other adjuncts. According to Risen, before 1906 and the Pure Food and Drug Act, it was not illegal to adulterate whiskey with caramel (but caramel remains widely used in spirit production today), fruit juices and “all manners of chemicals.”

Rectification represents another possibly confounding factor. Mike Veach, another ‘whiskey historian,’ explains that

“many of the Maryland distilleries before 1906 were actually rectifiers--plants that bought unaged whiskey from elsewhere, then redistilled it, or aged it, or added something to it to make a final product they could legally call whiskey.” (Risen)

If that were the case, discrete batches of the whiskey produced by a single rectifier might well vary.

5. More absence of evidence.

Risen and the experts he interviewed do not say why, or they more accurately should have said most, Maryland ryemakers never recorded their recipes. They may have wanted to protect their trade secrets from unscrupulous competition or simply handed down the formula from distiller to distiller. Maybe it is just that they agreed in concept with Emerson, Keynes and Smith.

The conditions that prevailed more generally in Maryland before the early twentieth century may have made inconsistency inevitable. If distillers bought what they could get, not only from different farmers offering rye but also corn or sometimes barley, and blended them in varying proportion depending on supply, then different batches would differ in composition and flavor.

None of this, however, would be remarkable unless different batches produced by the same distillery differed in flavor. After all, variations in style prevail throughout the world of whiskey. Irish whiskies share a discernable style but still differ widely in flavor among themselves, and distillers sharing regional styles of Scotch from the lowlands to the islands produce whiskies different from one another.

Risen is an editor at the Times and the author of several books about whiskey and whisky, but his failure to address the distinction is exasperating. He would appear to infer that a particular distillery did produce a consistent product. He thinks the factors he does address “might make the whiskey taste dramatically different,” not on a regular rotation at a given distillery but “from an identical batch made a few miles away.” (Risen)

If so, the entire article amounts to a great deal of noise about nearly nothing. He speculates that Maryland distillers used rye because it was a prevalent crop in the Midatlantic region, but “If there was corn growing nearby, they used that, too.”

T.W. Wright, however, who thinks otherwise, describes the development of Maryland rye in a more coherent and compelling way. This Wright traces its origin to England, noting that the country was the predominant source of early Maryland settlers, and its evolution into a distinct style through Ireland. He does not say so but the distillation of whisky remained a major English industry during the eighteenth century before Scottish competition gradually eradicated production.

The Irish connection is equally plausible. As Wright observes, Maryland unlike most of the mainland colonies attracted a disproportionate number of early Irish immigrants because it allowed catholic immigration from its inception, and unlike producers in other countries the Irish habitually distilled their whiskey three times, an unusual practice in North America except in Maryland where it was prevalent, in particular for the process of making rye.

Wright rejects the dichotomy that Risen describes between corn versus barley but agrees that the traditional formula was not fixed. Each recipe “has a mash bill of mostly rye, a lot of corn, a little of something else, usually malted barley but could be wheat or another grain” including surplus oats or on occasion buckwheat.

“The recipes vary, and they always have, but it’s the spicy rye cushioned with the sweet corn and just a hint of one or two other grains that gives Maryland Rye Whiskey its dynamic taste. It is delicate and bold, spicy and fruity, all at the same time.” (Wright)

Sometimes, he adds, “a bit of the rye grain was malted,” but again in conformity with Irish practice most of the grain, both the rye and corn, was not. Malting all the grain assisted in the process of fermentation but “could be a chore to be avoided” in the relatively “sparse” conditions of colonial North America.

The Irish had discovered that malting but a sparse amount of the grain produced enough of the enzyme that boosted fermentation. Maryland distillers followed suit. Adding a little barley malt had unintended consequence of creating that “dynamic taste.”

Something else that Risen overlooks could cause the whiskey to vary from batch to batch. The great majority of early Maryland producers were smallholders who grew multiple crops and traded for other goods. They typically repurposed their barrels to transport a range of goods in succession.

“A farmer might,” for example, “have used a barrel… as he moved [grain] and sold it to the mill. From there he might use that barrel to bring back to his town fresh oysters…. ” After that he might fill the barrel with raw whiskey. The farmer would of course attempt to wash the barrel after each use with boiling water but “the varying nuances and aromas could leach into” the staves.

As an expedient some farmers sometimes set their used barrels over fire to dry them, with another unintended consequence: The char flavored the whiskey further. (Wright)

So maybe the mystery of Maryland rye does not only amount to a clamor and bang that is just noise, or maybe it does. Wright cites no sources while Risen is not explicit enough for his reader to know. Moreover, none of this establishes whether or how long any of the various patterns prevailed.

6. The Homefield advantage in Massachusetts.

If Maryland rye from a given producer did vary from year to year or at least time to time, the pattern of production would not have been unprecedented. Jonathan Cook, chief Luddite, owner and brewer at Homefield as well as author of the equally contrarian Beer Terrain spots what ought to have been the obvious analogy in the elite vineyards of Europe.

“Wine drinkers,” he explains,

“are prepared to have a favorite vintage variety because they think of their drink as an agricultural product susceptible to seasonal influences. Couldn’t beer drinkers develop the same level of awareness?” (Cook 80)

The variation among a single vineyard’s vintages is, however, hardly unbound. Each year’s batch from a rigorous vintner remains recognizably that producer’s wine. Some of its characteristics may vary but its character is constant. It takes no guesswork to spot a Barolo or Bordeaux from a storied vineyard whatever its vintage and one will not be mistaken for the other or for anything else.

In practice Cook goes further. He is, it transpires, Emersonian as well as Luddite. “There is,” he insists, “a way to brand inconsistency. What the local fields offer is one-of-a-kind beers.” If, however, terroir offers one-of-a-kind wines, their styles are nonetheless replicable. Cook’s various beers, at least most of them, and there are a lot (hundreds during his first few years of operation alone) are not.

Elite vintners grow their own grapes but brewers including Cook himself ordinarily grow nothing. Nor does he malt the grain he buys. He is more circumscribed than anyone else by vicissitudes of supply because he sources everything within so tight a geographical radius. As paradoxical as it sounds, that policy, born from environmental concerns as well as his preindustrial philosophy more generally, guarantees that Cook will not brew beer as consistently as a grower of grapes can produce his wine or as consistently as a brewer with broader sources of supply.

The New England climate is particularly fickle, and its small farms sell what and where they can. Cook therefore will brew just about any style using the most catholic range of ingredients. So while the beers that result are recognizably his, they are not recognizably similar. Supply and limited capacity dictate style and drive demand.

Cook has imposed a purposeful limit in two respects. “New England brewers,” he maintains, “buy all the local supply and will, for the foreseeable future, keep it all to themselves” but nobody else in New England curtails the length of the supply chain as much as he does. (Cook 68) In addition, Homefield has a small brewing capacity and has no intention of expanding it. Growth is not good; it conflicts with a preindustrial aesthetic and ravages finite resources.

So does excessive profit. Homefield is a labor intensive project that relies on expensive ingredients compared to his competitors to the extent that he has any, but Cook does not price his drink or food at a premium.

The confluence of factors that constrain the amount of beer Homefield can produce and encourage Cook to improvise combine to make inconsistency the bedrock of a unique enterprise, at least for now. That is no mean feat. We should wish him well and join in hoping others will follow his sustainable example.

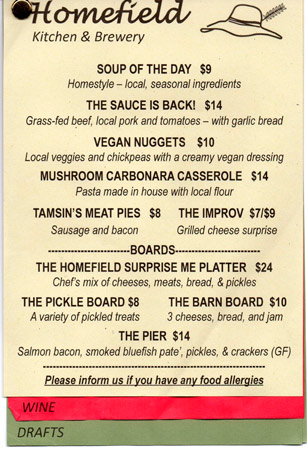

Lunch menu at Homefield: Surprise Me.

Lunch menu at Homefield: Surprise Me.

Sources:

Anon., “When the Facts Change, I Change My Mind. What Do You Do, Sir?” https://quoteinvestigator.com/2011/07/22/keynes-change-mind/ (22 July 2011) (accessed 25 July 2020)

Noel Busch, “Close-Up: Lord Keynes,” Life vol. 19 no. 12 (17 September 1945)

John Cassidy, “Postscript: Paul Samuelson,” The New Yorker (14 December 2009)

Jonathan Cook, Beer Terrain: From Field to Glass (Hardwick MA 2015)

Clive Crook “Beyond Belief,” The Atlantic (October 2007) (accessed 24 July 2020)

Ralph Waldo Emerson, “Self-Reliance” from Essays: First Series (Boston 1841)

C. Harcourt, “Joan Robinson 1903-1983,” The Economic Journal no. 105 (September 1995) 1228-43 “On the Influence of Piero Sraffa on the Contributions of Joan Robinson to Economic Theory,” The Economic Journal, Supplement: Conference Papers (1986) 96-108

Brennen Jensen, “Local Liquor: A spirited look at our homegrown hooch,” Baltimore City Paper (27 January 2015)

M. Keynes, “Letter to the Editor,” The Economist (25 March 1933)

Pankaj Mishra, “Other Voices, Other Selves,” The New York Times (14 January 2010)

Clay Risen, “Maryland Rye Whiskey Has Finally Returned. But What Was it in the First Place?” The New York Times (14 February 2019)

John Williams, “In ‘Intimations,’ Zadie Smith Applies Her Even Temper to Tumultuous Times,” The New York Times (22 July 2020)

T.W. Wright, “What is Maryland Rye?” Maryland Distillers Guild, https://marylandspirits.org/what-is-maryland-rye/ (11 December 2017) (accessed 29 July 2020)