A note on Boston brown bread.

It is not in reality bread at all, and the overwhelming number of Americans cannot get it, and if they could, would not get it. It is not for sale beyond New England so its survival as a commercial product is all the more precarious; consider the demise of the pilot cracker, beloved of Yankees but unaccountably killed by Nabisco, the villain of that piece.

Almost nobody else in the world has heard of brown bread. It is a derivation of several ‘thirded’ or ‘third’ baked goods indigenous to New England, made since the seventeenth century in some form or another with a mixture of three flours, in its case corn, rye and whole wheat. The palette of brown bread would appear medieval in its amalgamation of savory and sweet like the baked beans seventeenth century Puritans brought with them from England to the Shawmut Peninsula. The beans like the bread juxtapose savory and sweet, mustard and molasses, this last also an essential component of Boston brown bread.

2. British food in early America.

Brown bread is an apotheosis of British food adapted to American conditions and crops. The combination of its three flours never would have gained traction in early modern Britain. Cornmeal was unknown there before the settlement of North America and until late in the nineteenth century was for the most part reviled while wheat, white flour not the whole wheat used for brown bread, was favored over rye. Reputable bakers therefore did not dilute precious wheat with other grains.

Early English settlers in North America did not abandon their initial preference for white bread but the climate of colonial New England demanded adjustment and improvisation. Wheat was hard to grow, rye not so bad, corn the default survivor.

With the characteristic rigor that most culinary historians lack, Keith Stavely and Kathleen Fitzgerald point out in concrete terms just how difficult early New Englanders found the cultivation of their desired breadcrop. During

“ ….the 1640s and 1650s, more than twice as many acres tended to be planted in corn as in wheat, and each acre of corn yielded more than double what each acre of wheat yielded…. Thereafter, throughout New England even this level of success with wheat became difficult to achieve, due to a variety of impediments, most especially those arising from a wheat fungus known as the blast.” (Founding Food 24)

3. A pudding in disguise.

Why then apotheosis? Brown bread, it turns out, is not strictly speaking a species of bread at all. It is in terms of technique a classic British steamed pudding, originally cooked in a cloth or basin; as late as 1896 the preternaturally frugal Fannie Farmer recommended using “a melon-mould or one-pound baking powder boxes” and, alternatively, “a five-pound lard pail.” (Farmer 60) Perhaps another index of New England thrift, the brown bread made at home (if anyone at home still makes it) over the succeeding decades customarily has been steamed in… a used coffee can. The tradition may explain why, unlike other ‘bread,’ commercial brown bread still comes in cans.

4. Nemesis

Brown bread has become deeply unfashionable, even in the region of its birth. Serious restaurants of recent years hopelessly hoping to revive the traditional foodways of New England have found next to no demand for it. That is a shame.

But why is it a shame? Brown bread would appear so incongruous enough to twenty first century sensibilities not to merit mention, an oddity along with those long disdained medieval meat pies loaded with sugar, rosewater, herbs and spice. Then again, mincemeat endures, if only during the holidays all over England and, to a considerably lesser extent, New England. Traces of our medieval tastes remain, in a shadowy way.

At Townsman while its short run in Boston lasted, Matt Jennings served every diner a disc of his reinvented ‘New New England’ brown bread perched atop a can, an emphatic allusion to domestic tradition. Before it became what amounts to an upscale burger joint, Loyal Nine in East Cambridge, the neighborhood an epicenter of culinary innovation in Boston, once upon a time paired brown bread with soused fish, variously bluefish, butterfish or mackerel. The slightly sweet, roughly textured bread was a beguiling foil for the vinegared oily fish and by rights should remain on the Loyal Nine menu but, as with most of its attempts to reinvent the food of early New England, customers demurred.

In fact the oddity of brown bread, limited by current custom to service with hot dogs and those Puritan beans--always the Saturday supper at my grandmother’s kitchen, and as children we relished Saturday supper there--works with lots of other foods both savory and sweet. A slather of cream cheese is traditional, but add or substitute marmalade, eat the bread with ham, or ham glazed with marmalade, or roast pork or fresh fruit….

5. The invention of tradition.

If the concept of brown bread appears definitively medieval, its roots may not dive so deep, an indication perhaps that old English foodways endured in the attitudes of New England cooks toward innovation, a culinary take on the fashion trope that everything old may become new again.

Arthur Brayley, among a handful of authors to address brown bread, traces the first batch of it to a single year, day and person. His essay on the subject appeared during 1906, appropriately enough in the journal of the Boston Cooking School. The school by then had been made famous in the city by Mary Lincoln and nationwide by her more famous protégé, Miss Farmer herself. That was back when New Englanders took pride in brown bread not only as a culinary treat but also as a badge of identity: Brayley goes so far as to muse about asking the Commonwealth of Massachusetts “to make the invention of Boston brown bread a legal holiday.”

Brayley believes brown bread “was first given to mankind by Major Nathaniel Thwing, of Boston, Mass., July 7, 1746.” (Brayley 397) That kind of precision may appear implausible but at a glance Brayley apparently is persuasive.

6. Hard times…

“It was at the time,” Brayley writes of 1746,

“that the victories of Louisburg were being paid for by the colonists at a greatly increased public debt, and all institutions and persons that depended upon incomes found themselves in a condition of distress, for the currency had depreciated to an alarming extent.” (Brayley 397)

Louisburg had been the fortress on Cape Breton Island that guarded French North America from naval assault and doubled as a base for privateers preying on British shipping. Few if any Bostonians realize it, but the city’s most coveted address, Louisburg Square nestled deep in Beacon Hill, gets its name from the city New England militias seized for the British crown in 1745.

7 …as mothers of invention.

The unanticipated fallout from battlefield success, an economic depression, had given Thwing his chance and he took it.

Brayley argues that because local authorities in early colonial Massachusetts regulated the sale of bread with ruthless efficiency to prevent price gauging and adulteration, the absence of legal or commercial evidence describing thirded breads before 1746 indicates that bakers had not sold them.

“As early as 1681,” Brayley found, “a law was passed authorizing the selectmen of each town to regulate the price of bread.” The towns policed their regulations, “which they enforced to the letter.” (Brayley 404) “In order to guarantee quality and quantity,” he explains, bakers therefore “were compelled to stamp every loaf coming from their ovens with the first letter of their Christian names, and the first and last letters of their surnames.”

In Boston the authorities not only set prices but also specified the amounts and, where applicable, proportions of grains allowed for loaves of each kind of bread. (Brayley 404-05)

Baking bread was a privilege, not a right, and Brayley found no record of any baker other than the major with a permit to sell brown bread for about a decade or so: “For years Major Thwing had a monopoly of the brown bread business in Boston.” (Brayley 405)

All this presumes that the early records are comprehensive and the research Brayley conducted was rigorous, a difficult pair of assumptions to test, but any number of other authors date Boston brown bread to the colonial era, many of them if without citation to the seventeenth century. (See, e.g., Hazard, Kimball)

7. Not so fast, or early.

Not all that is apparent however is real. Brayley does not mention the inclusion of molasses, the combination of more than two flours or the steaming of bread. After all Major Thwing was a baker; his bread was not steamed. It becomes apparent that he was not selling Boston brown bread as we know it, and if print items amount to reliable sources it is not all that old.

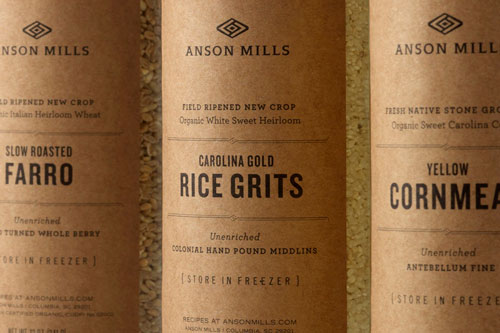

In its own recipe for Boston brown bread the fastidious Anson Mills hints at the historical reality:

“Brown bread descends from thirded breads, rustic farm breads made of coarse grain meals and mineral-rich sweeteners--hearty rural fare that fortified against cold temperatures and calorie depletion, following in the tradition of foods related to work.”

So far so good but then Anson Mills goes on to elide its own distinction between thirded and Boston brown bread. “After our Revolution,” the mill maintains, “pearlash-leavened thirded bread became popular throughout the Colonies, particularly one known today as Boston brown bread.” (Anson Mills) The elision may simply reflect sloppy drafting; after the revolution of course colonies no longer existed as such.

Anson Mills products

Both Lincoln and Farmer sustained the distinction late into the nineteenth century: It was significant to them. Each author included a number of recipes for thirded breads along with one for Boston brown bread in her cookbook. Other authors of the time followed suit. (see, e.g., Putnam 2-3)

Boston brown bread did first appear after the revolution but not nearly as early as Anson Mills appears to infer. Keith Stavely and Kathleen Fitzgerald, peerless authorities on colonial and early national New England foodways, have found no print recipe for ‘steamed brown bread’ before 1862 and none that includes ‘Boston’ in the description “with any frequency until the 1870s.” (Northern Hospitality 360, 361)

The creators of those early iterations understood the lineage of the technique. One of the 1862 renditions notes that it may be “used as a pudding.” (quoted at Northern Hospitality 360)

8. An example of communitarian culture in New England.

By then steamed brown bread already had achieved its iconic status in New England. As Stavely and Fitzgerald explain, because of its debt to the early modern thirded breads, “this new loaf took on an antique aura.” “The presence,” they add, “of no fewer than four recipes for steamed brown bread” in an 1898 community cookbook from Meriden, Connecticut, “points up the bread’s importance as both food and symbol.” (Northern Hospitality 361)

As those Saturday suppers at my grandmother’s house demonstrate, the bread had become important indeed. Again from Stavely and Fitzgerald:

“In the mid-twentieth century Bowles and Towle gave us brown bread in jingle form: ‘Three cups of corn meal, / One of rye flour; / Three cups of sweet milk, / One cup of sour.’ And so on. Boston Brown Bread thus became the stuff of twentieth-century nostalgia.” (Founding Food 29)

So Boston brown bread is one of those foundational foods, along for example with chowder in its modern guise or steak and kidney pudding, that evolved out of considerably earlier preparations but only during the nineteenth century. Whenever it first appeared, the pudding deserves revival in our domestic kitchens. In the meantime cans of brown bread from B&M in Biddeford, Maine, are not so bad.

Sources:

Anson Mills, “Boston Brown Bread,” https://ansonmills.com/recipes/437 (n.d.) (accessed 6 September 2020)

Arthur Brayley, “Boston Brown Bread: An Historical Sketch,” The Boston Cooking-School Magazine of Culinary Science and Domestic Economics Vol. x, no. 7 (June-July 1905-May 1906)

Fannie Merritt Farmer, The Boston Cooking-School Cook Book (Boston 1896)

Jessie Hazard, “Classic steamed brown bread is a sweet treat,” the Boston Globe (4 November 2014)

Matt Jennings, Homegrown: Cooking from My New England Roots (New York 2017)

Christopher Kimball, “Bringing Back Brown Bread,” Cook’s Illustrated (29 November 2016)

Jonathan Norton Leonard, American Cooking: New England (New York 1970)

Mary Lincoln, The Boston Cook Book (Boston 1901)

Elizabeth Putnam, Mrs. Putnam’s Receipt Book and Young Housekeeper’s Assistant (New York 1862)

Keith Stavely & Kathleen Fitzgerald, America’s Founding Food: The Story of New England Cooking (Chapel Hill 2001)

Northern Hospitality: Cooking by the Book in New England (Amherst MA 2012)