A note on a stubborn resistance to Yankee foodways.

Boston has, despite itself, very nearly become the San Francisco of the east. The ascent of the technology industry has brought prosperity but also titanic property costs to a city that not so long ago was, like Philadelphia remains, extremely good value in real estate terms. Now for the first time the cost of living in Boston has outpaced even New York with the attendant attenuation of inequality.

The influx of tech companies also has cost Boston a slice of its soul. The character of the city hangs perpetually in the balance; so high a proportion of students sees to that. Best now to seek the essence of urban New England some fifty miles southwest in Providence.

One of the oldest Boston traditions has been one of the hardest hit. Nearly all the old guard restaurants serving the distinctive traditional cuisine of New England have disappeared. For a time when they still flourished during the late seventies until the early nineties a number of innovative newcomers joined them.

2. A renaissance of sorts falters.

But Biba, where Lydia Shire served “lobster pizza and Fannie Farmer’s Chantilly potatoes alongside beer-battered calves’ brains” (Mennies), the Colony, Jasper’s and Seasons in the then new Bostonian Hotel, noble efforts to revive New England cuisine in modernist guise, are decades gone, and Jimmy’s Harborside along with Anthony’s Pier 4, the big old waterfront fish houses, followed in turn.

Seasons Restaurant at the Bostonian Hotel

The boomlet in a revived New England cuisine was entrancing enough while it lasted. Parker’s in the fabled Parker House Hotel pushed a New England envelope. Two national luminaries based in Boston, Shire and Jasper White (later of, yes, Jasper’s) ran its kitchen, and then the one at Seasons, “where they put caviar on Rhode Island-style johnnycakes and turned humble cellar staples like parsnips and cabbage into fine-dining-worthy dishes.” (Mennies) Parker’s held its own but dinners at Seasons were sublime.

Parker’s does survive, but only with an anodyne menu, the kind of thing that used to be called ‘continental.’ Other than its Parker House Rolls and a desultory chowder the dishes it lists might appear anywhere.

3. The sorest loss.

Of those reinterpretive losses the Colony remains at a distant remove the saddest. Its kitchen tacked strongest toward early New England, not only toward its ingredients but also to dishes long unfamiliar to the modern palate. This was authenticity--not a tomato near the place--and it was, while it lasted, wonderful, although the house might have been less frosty. The dour greeting and stiff service were, however, typical of its time. Maître d’s then were not yet cheerleaders but rather gatekeepers, not so much to keep anyone out as to signify the serious intent of the establishment; understandable perhaps but unfortunate nonetheless.

As Leah Mennies noted in a contemplative essay two years ago about the absence of Bostonian interest in traditional New England foodways, the two owners who doubled as its chefs at the Colony had

“decided to go all in on Colonial cuisine, studying live-fire cooking techniques at Plimoth Plantation and poring over the cookbooks at Harvard’s Schlesinger Library before opening a white-tablecloth restaurant on Boylston Street.” (Mennies)

When the restaurant appeared in 1986 Boston magazine awarded it best new restaurant. Too few of us cared. According to Corby Kummer, “diners dismissed it as a stuffy, foodier Sturbridge Village.” (Kummer) That species of displaced disdain is typical of those Bostonians old and new who believe anything in Massachusetts west of Brookline amounts to Appalachia.

There is in fact something laudable about the lonely vigil of Sturbridge Village. The Village engages in serious historical research, including culinary research, despite its need, in common with Colonial Williamsburg and other ‘restored’ architectural ensembles to engage in anachronism. Halloween walks and Christmas pageants attract the tourist trade that sustains them. Popular education was, after all, the focus of their original purpose.

4. The great extinction.

By 1990 the imaginative experiment that was Colony had failed and but a handful of Boston restauraunteurs have attempted stabs at a reinvigorated Yankee cooking since. They, however, have been compelled by the lack of enthusiasm for the concept incrementally to deracinate the traditional cast of their menus.

More recent closings include what had been some of the oldest and most legendary restaurants in America; scoffers may be surprised that Boston ever held culinary sway over the United States but in reality Fannie Farmer dominated the culinary consciousness of the country from the 1880s until she was eclipsed by The Joy of Cooking after 1931. Even then Farmer remained the cookbook of choice in New England for decades longer.

Those lost luminaries include Durgin Park, Jacob Wirth’s and, most iconic of all, Locke Ober, especially in its later years under Lydia Shire, where the careful cooking, maybe best of all the lobster stew beloved of JFK, did not disappoint any of us.

Locke Ober in 2009

Were all these legends wonderful all the time? Jasper’s was, and Biba, the Colony, Locke Ober and Seasons. Some of them were not, and that is not the point. Durgin Park and Jacob Wirth’s did not pretend to reach for the sublime. Instead they offered comfort. And anyway some of the uneven food was better than good, roast pork with cornbread stuffing, for example, or a mountain of grilled chicken livers at Durgin Park; fish chowder, sausages and their trimmings at Jacob Wirth’s.

5. A holdout.

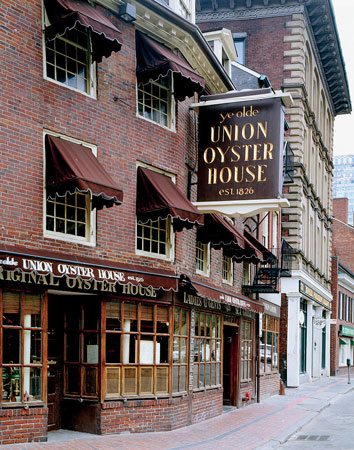

The sole survivor of the Old Guard, the Union Oyster House in Haymarket, remains a stunning architectural artifact that has refused to embalm itself in the polyurethane so beloved of historical buildings in Charleston, South Carolina, and Georgetown, in DC; no overbuffing for Boston.

The original semicircular oyster bar, its wooden surface slowly scooped smooth and concave over the centuries, dominates the groundfloor dining room; booths of painted wood frame its perimeter in a warm way.

The oysters are pristine, the rest of its simple menu fair. Daniel Webster, a regular customer, washed down dozens of oysters at a sitting with tall tumblers of brandy and water. He favored the contingent conviviality of the oyster bar.

JFK (there he is again), another regular a century or so later, preferred the privacy of a mahogany booth upstairs.

6. Try try again.

The Yankee legacy is not entirely lost, although its best recent exponent survived for only four years. After a long run at cozy Farmstead in Providence, Matt Jennings made the mistake of moving north to open the sprawling Townsman in the glassy atrium of a slick skyscraper in Downtown Crossing.

Jennings could neither make the rent nor sustain the hyperfueled persona that had overtaken him. That was a shame: Jennings demonstrated that New England cuisine is ripe for relevant revival but, typically, Boston diners demurred.

You can, however, try to pour some of his lightning into your bottle by buying the engaging but admittedly aspirational Homegrown, the cookbook that more or less attempts to replicate for domestic kitchens the innovative Yankee experiment that was Townsman. A James Beard Award finalist, Homegrown itself had but the briefest half life. It now may be bought at a heavy discount from our surviving bookshops as well as online.

7. A sort of self-loathing.

The refusal of Bostonians to embrace their culinary heritage, curious in the same manner as native New Yorkers loathe their own distinctive accent, is not unique. In much the same way Londoners disdained English restaurants a few decades back. A handful of exceptions included Drake’s, The English House, Rules and some outstanding hotel rooms including the expensive one at the expensive Connaught. All those kitchens other than Rules have closed. To be fair however holdouts have endured in the avenues of St. James. Clubland never lost its appetite for the ‘solid sufficiency’ of traditional English dishes.

Before the plague at least, London finally had embraced the food of its English hinterland; the Holborn Pie Room, Rochelle Canteen, Rules itself and St. John are but a few of the hottest restaurants in town. They all serve British specialties or, as Rules describes it, “the food of this country.” Boston however still displays scant affection for its own historic foodways.

Two years ago Mennies posed a couple of questions about the traditional food of New England. What comes to mind? Things like chowder, fried clams, cider doughnuts and roast turkey come to mind.

“But what,” she goes on to ask, “about high end New England cuisine? Confused?” Mennies then immediately admits to a certain sleight of hand:

“Don’t worry--it was a bit of a trick question. You see, in Boston, there isn’t much of that around--and what is around is largely misunderstood.”

Much of that misunderstanding is willful; “try to take Yankee dishes upscale, and you’re likely to hear a singular refrain: ‘I don’t get it.’” Willful because the inflexibility does not extend to extraneous cuisines:

“…. [W]hile diners might be accustomed to encountering new-to-them Middle Eastern spice… a Revolutionary War-era dish that’s fallen out of the modern lexicon has ended up being a much tougher sell.” (Mennies)

The past, it would appear, remains the most foreign country in culinary terms, at least to New Englanders and, in terms of New England cuisine, to Americans more generally.

Five years ago Kummer wrote that “Boston’s braver chefs are in the process of reinventing New England’s culinary vernacular.” He attributed the trend to the influence of Kitchen, a South End innovator

“that took inspiration from sources as disparate as Gilded Age New York, Fannie Farmer, and Julia Child, with a dash of Ye Olde England thrown in for good measure.”

Kummer conceded that even Kitchen was not quite the culinary avatar he would have liked to identify: It “improbably survived, mostly by reducing its emphasis on historical oddities and concentrating on simple New England fare.”

He explains that he considered chefs attempting the regional revival “‘brave’ because restaurants based on this approach often don’t become smashing successes,” an almost comical understatement citing the cautionary Colony tale. (Kummer)

A couple of years later he could have added Kitchen itself to the string of failures. It has not survived either, although apparently less from its desertion by diners, more from the loss of its liquor license. Still, its’ owners subsequent venture looks to Italy instead of New England.

8. Revival redux, and then retreat.

Two keepers of the New England flame, if only a flicker, deserve a (qualified) note. Their original intent was no reverential replication of the old recipes but rather the referential interpretation of them in modernized guise. Vague enough reference as well; chefs ambitious enough to reinvent the regional cuisine upon opening have not found much of a market and therefore have retreated to the merest allusive notes.

Puritan & Co. appeared first and in the immediate context merits little discussion. When it opened in 2012, the menu included a number of innovative dishes recognizably adapted from the New England past; “an artfully arranged ‘boiled dinner’ vegetables [sic], bluefish pâté served alongside homemade hardtack crackers, and deconstructed clam chowder.”

All those dishes have disappeared. “We have,” admits the owner, “never been busier since our food has been more… ‘suggestive’ New England.” (ellipses in original) Suggestive is too strong a term; in fact the current Puritan menu includes but one wan nod to New England, the Parker House Roll. Otherwise the usual Mediterranean suspects now hold sway. (Mennies)

Marc Sheehan at Loyal Nine tried harder, for a while. He also chose the more esoteric if somewhat misleading name.

9. The first Loyal Nine.

The original purpose of the Loyal Nine was to exploit the enthusiasm for violence of Boston street gangs, a manifestation of the belief, baleful enough most of the time, that ends justify means. The nine men in question met through their common membership in one or more of the interlocking, secretive and powerful Whig caucus clubs that had become organized in Boston by the 1760s. Oddly enough their name did not arise initially from the function they would fulfill but rather derived from the term ‘caulker’ because so many of the earliest members were shipwrights.

Three of the clubs, the North, Middle and South caucuses, met in the private rooms of taverns where they plotted to “carry town meetings and general elections even when they did not represent the wishes of the majority.” (Forbes 119)

The ambition of the shadowy clubs, “to see to it that Boston was run according to the wishes of the Whig party,” was breathtaking, nothing less than the creation of an illegal alternative government. Their success was as astonishing as that ambition.

Colonial New Englanders paraded their antipathy to the catholic church by celebrating “Pope’s Day,” a North American modification of the traditional Guy Fawkes commemorations. By the middle of the eighteenth century the ‘celebration’ in Boston had evolved into a day of rioting.

Two gangs in particular waged pitched fights in their attempts to steal and destroy the elaborate carriages resembling modern floats that they paraded through the streets carrying “effigies of popes, bishops, and devils.” (Bernson) It was serious business: “People were killed and maimed for life.” (Forbes 94)

During the festivities of 1765, the South End gang “brutally defeated the North End gang.” It was the prowess of the victors that attracted the attention of the Loyal Nine. They made clandestine contact with Ebenezer MacKintosh, the lead gangster, to collaborate on forcing Parliament to repeal the Stamp Act. (Bernson)

His success was spectacular. After foiling repeated attempts by the authorities to cut down effigies from the Liberty Tree the gang had created, including an effigy of the official responsible for enforcing the Stamp Act, the gang took the effigies to the official’s house where they beheaded then burned them before ransacking the house.

The mob mayhem was malevolent enough to force the official to flee to the refuge of Fort William on an island in Boston Harbor. Soon afterwards MacKintosh led a mob to the substantial house of Governor Hutchinson, which they burned to the ground. The level of violence, as Alexandra Berson, archivist at the State Library of Massachusetts, wryly notes, “may not have been part of the original plan.” (Bernson)

Governor Hutchinson, made homeless by the Loyal Nine and friends

The caucus clubs and Loyal Nine would become the directing force behind

“that largest and most mysterious club of all--The Sons of Liberty…. It was they who established a mob rule in Boston which was stronger than any law courts. It was they who frightened the customs commissioners out of town, who bullied and threatened ‘importers,’ who tarred and feathered ‘informers,’ who paralyzed all government but their own.”

Unlike so many other underground organizations down the years, the Sons of Liberty behaved with a certain benevolence toward the general population if not of course the officers of the legitimate government. “Although it was mob rule, it was, as a puzzled observer wrote back to England, ‘a trained mob.’” (Forbes 125)

Why the Nine decided to call themselves ‘Loyal’ itself may appear something of a mystery. The misnomer they chose would appear apparent, although ardent patriots adhered as long as they could to the fiction that their position amounted to the true defense of British constitutional liberties.

10. Back to the future and to the past (sort of).

The naming by Sheehan of his restaurant is misleading because from its inception the Loyal Nine did not aim to reimagine the foodways of colonial Boston or even New England. Instead its original menu focused “more generally on the East Coast--with an emphasis on the coast” and seafood. (Martinelli) The frontpage of the restaurant website still bears the banner “East Coast Revival.”

At least the original focus was on reinventing traditional foodways. Sousing is one of the older English techniques, a sort of bright quick pickle of vinegar and onion to cook and preserve oily fish without a big dose of salt. At the outset Loyal Nine paired Boston brown bread, itself a bit of an artifact, with soused fish, variously bluefish, butterfish or mackerel. The slightly sweet, roughly textured bread was a beguiling foil for the souse and its equally English horseradish sauce.

As late as 2018 Sheehan still was serving smoked haddock sauced with something based loosely on pondemnast, an Algonkian corn porridge.

He took titular liberties in both directions, by giving untraditional dishes traditional names and renaming traditional dishes something else. His “Aroostook savory supper” for example simmered layers of onion, potato and salt pork in a crock. That is nothing less than an early incarnation of chowder. (Perkins, passim)

There were imaginative eighteenth century sallets, or salads; a dish of fermented beef braised in lard and tallow; lobster also braised, in mead with hickory nuts; and even the irresistible English brown bread ice cream otherwise absent from this arc of the Atlantic rim.

The name of another dessert, called brewis, was another misnomer. At Loyal Nine it is a sourdough chocolate bread pudding; historically, as the indispensable Dorothy Hartley explains, it is a savory broth that originated in Wales:

“In the earliest recipes, oat shells were stirred and soaked…, the clear liquid poured off, and the lower thickness boiled till it becomes a thin broth (not so unpalatable as it sounds). This, with a lump of bacon fat, pepper and salt, made the palatable gruel called ‘brewis.’”

The dish did evolve:

“In a later form the boiling water was poured on to crumbled oatcake, the dish was covered, and cooked on the peats for 10 minutes or so. Butter, pepper and salt were added and it was eaten hot from the hot basin with a horned spoon (you can eat hot things hotter with a horned spoon).”

By the 1950s brewis had become simpler still, fine crusts of any bread moistened by boiling water and served only with butter and pepper. (Hartley 526)

Sheehan may have named his pudding in a nod to Caroline Howard King, who describes the brewis her mother made in Salem during the 1820s as “little crusty bits of brownbread stewed in cream,” still however a league or two afield from something sweet and chocolate. (quoted at Northern Hospitality 348)

Whether or not the ‘historical’ dishes at Loyal Nine had much of anything to do with traditional foodways no longer matters much; all of them are gone from its menu.

So the Union Oyster House stands solitary vigil holding out, perhaps in vain, for a kindred soul.

Incidentally the chowder usually served in Boston is terrible, its texture typically a traverse from wallpaper paste to Krazy Glue. Get to Providence, Newport or, best, South County in Rhode Island for better bowls.

Sources:

Anon., “Loyal Nine,” https://www.encyclopedia.com (2 December 2020) (accessed 30 November 2020)

Alexandra Bernson, “The Loyal nine, a secret precursor of the Sons of Liberty,” State Library of Massachusetts, mastatelibrary.blogspot.com/2016/08/the-loyal-nine-secret-precursor-to-sons.html (August 2016) (accessed 30 November 2020)

Devra First, “History made by hand at Loyal Nine,” the Boston Globe (26 May 2015)

Esther Forbes, Paul Revere and the World He Lived In (Boston 1942)

Dorothy Hartley, Good Things in England (London 1954)

Corby Kummer, “Restaurant Review: The Loyal Nine,” Boston, https://www.bostonmagazine.com/restaurants/2015/11/24/loyal-nine-restaurant-review (24 November 2015) (accessed 18 November 2020)

Matt Martinelli, “Colonial Style: A Cambridge eatery aims to add some historical flavor,” The Improper Bostonian, https//www.improper.com/food-drink/colonial-style/ (20 February 2015) (accessed 15 December 2020)

Leah Mennies, “Why Don’t New Englanders Like New England Cuisine?” Boston, https://bostonmagazine.com/restaurants/2018/11/20/new-england-cuisine (20 November 2018) (accessed 18 November 2020)

Blake Perkins, “An Enquiry into the Derivation of Chowder,” Petits Propos Culinaires 109 (September 2017) 31-66

MC Slim JB, “Olde and New: Historical and modern New England meet in East Cambridge,” The Improper Bostonian, https://improper.com/food-drink/olde-new/ (29 may 2015) (accessed 19 November 2020)

Keith Stavely & Kathleen Fitzgerald, Northern Hospitality: Cooking by the Book in New England (Amherst MA 2011)