Occasional miscellany, or, Never buy a dead lobster: The strange enough life & kitchen of Daisy Breaux, along with notes on Oliver Herbert, a pair of midcentury originals.

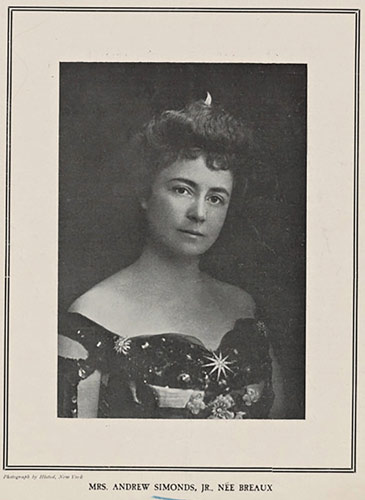

Margaret “Daisy” Rose Anthony Julia Josephine Catherine Cornelia Donovan O’Donovan Breaux, then Simonds eventually followed by Gummere and Calhoun was “what today would be called a professional event-planner for high-society functions.” ( UnXld 162)

When she married her first husband The New York Times described the wedding, held at St. Louis Cathedral in 1885, as “the most brilliant social event seen in New-Orleans for years.”

In the gushing style that remains a touchstone of its wedding coverage, the Times continued that the bridal procession itself represented “the flower of Carolinian and Louisianan aristocracy.” The ceremony would be “remembered as the flower wedding” because its ten bridesmaids wore costumes covered in wildflowers. (“Wedding Bells”)

The social scenes in question did not include New Orleans but started in Charleston, moved to New Jersey and then above all flourished in Washington, DC, where she lived with a politically connected husband; following his death her social prominence continued unabated. Her dining rooms if not Breaux herself would become a center of influence in political circles for decades.

Breaux entitled the memoir she wrote in 1930 at the age of sixty six The Autobiography of a Chameleon. The name she chose was no exercise in self-denigration but rather a celebration of her social versatility.

Widowed three times, Breaux supervised the design and construction of a massive pile for each husband in turn and “frequently presided over luncheons and dinners at the behest of financial leaders and visiting dignitaries.” Clients or guests included the future if short reigned Edward VIII, Grover Cleveland, Theodore Roosevelt, William Howard Taft and Woodrow Wilson. (“From The Publisher”)

Despite all the glitter and social prominence Breaux endured hardships. Evidently she had attracted controversy in Charleston, where “this clever and ambitious lady” was “regarded by the local ladies with suspicions both general and specific (including the patrimony of her child and the authenticity of a visiting French novelist).”

None of the backbiting prevented her from persuading Roosevelt to come to tea “by telling him that such a gesture would make happy the last days of an old servant of hers, a former slave.” (Swaim 190-91)

Following the death of her first husband she struggled to support herself and her daughter, perhaps in part due to the antipathy of those other Charleston socialites. The resourceful socialite improvised by converting the magnificent mansion she had built into a hotel that flourished until she landed her second husband “when they both happened to be aboard the same yacht during a congressional junket to the Panama Canal.” (Jones)

Villa Margherita, Daisy’s Charleston manse.

“And through it all,” The Atlanta Constitution claimed on publication of the memoir, “Mrs. Calhoun played the part of the chameleon, not merely reflecting her surroundings, but, like the human chameleon, coloring vividly the life about her.” The author of the review cited some light verse to buttress his point:

“Always she has proven herself like that little animal who, in the words of Oliver Herford,

‘Has the gift, extremely rare,In animals of savoir faire;And if the secret you would guessOf the chameleon’s success;Adapt yourself with greatest careTo your surroundings everywhere.’” ( quoted by Sparks)

3. Wilde whimsy.

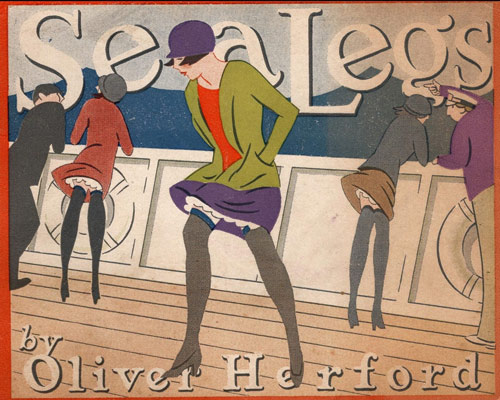

Herford himself is a fascinating if flimsy figure, the author of other light verse, coiner of humorous aphorisms and comic artist of some talent. This kind of thing is harder than it first may appear. “Whimsicality,” as F. F. Van de Water, a noted journalist and historical novelist, explained during 1931 in what then was the New York Evening Post ,

“is a substance far more dangerous to the possessor than deadly drugs… To be master of this treacherous, perishable quality requires firmness, delicacy, a youthful heart and the wisdom of age. To the person who snaps that there isn’t anyone with all those virtues we merely point to Oliver Herford.” (ellipses in original) ( Sea Legs inside rear cover)

In his time he was so celebrated that commentators called him, inappropriately, the Oscar Wilde of America. Herbert was neither a raconteur of Wilde’s caliber (nobody was) nor semicloseted gay but seems to have been a lot of fun.

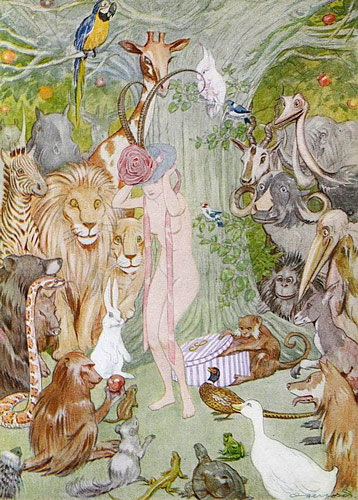

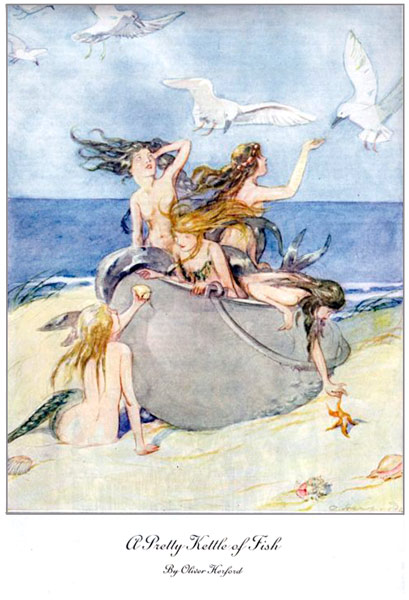

He liked to draw pretty girls. As noted, also in 1931, by William Rose Benét, editor, Pulitzer winning poet and older brother of Stephen Vincent,

“Oliver Herford’s drawing has always delighted us… his pretty girls are really pretty and his animals are simply masterly.” (elipses in original) ( Sea Legs rear cover)

The girls include scantily clad sirens and chaste nudes--Aphrodite, Eve, those jungle animals ogling a naked Eve for his Deb’s Dictionary , mermaids in a watercolor called ‘A Pretty Kettle of Fish’ among others.

One of his illustrated books of verse bore the double entendre Sea Legs. It follows one of his favorite formats, taking each letter of the alphabet as a vehicle for light verse and saucy illustration.

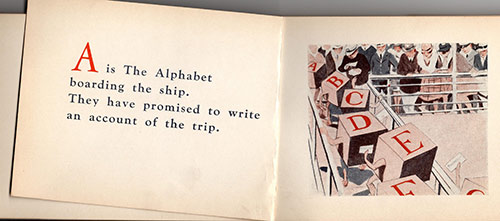

The book begins with a charming conceit:

“A is the alphabet boarding the ship.

They have promised to write an account of the trip.”

And so they do. Examples:

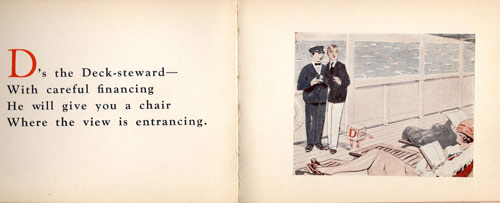

“D’s the Deck-steward

--With careful financing

He will give you a chair

Where the view is entrancing.”

And:

“E’s the Electrical Horse

in the Gym

It won’t take you far

But ‘twill keep you in trim.”

And later:

“O is the Ocean

a watery waste

With a nauseous motion

And terrible taste.”

And then:

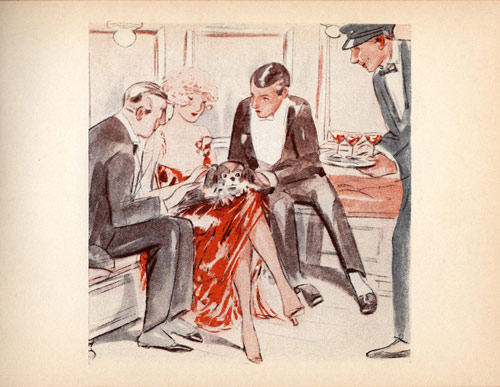

“P is the Pet on his

Mistress’s knee

Oh who woudn’t

Envy a Puppy

At sea!”

And so on until finally

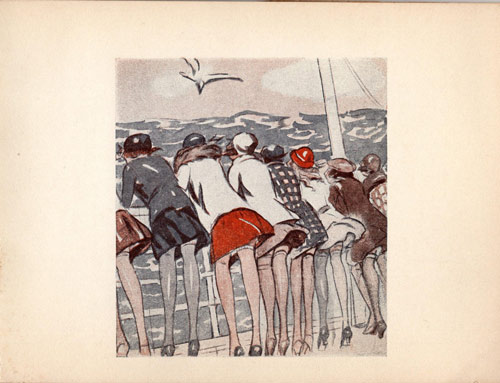

“W’s the Whale

where it is, I don’t know

But someone saw something

A moment ago.”

Followed by arrival in port which, in common with the outcome of the Breaux boondoggle to Panama, turned out quite well indeed:

“X-Y-Z is the Cable

They sent from the ship--

De-coded, it reads All Well Had

Elegant Trip.”

4. Second thoughts.

Eight years after the Chameleon Breaux decided to write a followup that would settle scores by revealing how she had been targeted as “prey for many of the scoundrels and racketeers that infest Washington.”

Discretion however would prove more profitable so she reverted instead to her socialite persona. Breaux herself quotes doggerel to describe her ‘philosophy of life:’

“If life is not as you would make it You can, at least, show how to take it; If you must ‘take it on the chin’, Then learn to take it with a grin; For, if you keep on ‘Smilin’ Thru’ Life’s Mirror will smile back at you.” (Jones)

So instead of taking the literary revenge tour, in 1945 she wrote what Don Lindgren and Mark Germer consider a “peculiarly American, socially ambivalent work associated with the national capital; half-cookbook, half-memoir.”

As they put it with some delicacy Breaux was, in common with the segregationist Wilson, a product of the “frankly unreconstructed South.” Her “sensibilities were Dixie upper-crust…. Though it cannot be said to characterize her generally, she could at times be attracted to good works.” ( UnXld 162)

5. An intermittent eleemosynary impulse.

Among the good works was her creation in 1921 of the Women’s National Foundation devoted to promoting “the influence of women in society.” It would not last long; as Lindgren and Germer infer, Breaux had a short attention span when engaged in her various charitable pursuits. The foundation sprang from an epiphany provoked while she attended the Democratic National Convention in San Francisco. As Breaux told the Cambridge Sentinel,

“I had gone out… with very little interest in suffrage--I was reared in Louisiana and I confess to still nursing the old traditions of the South as to men doing the work and big things and women confining their influence to the home and community. As the convention progressed, my eyes were opened. I was simply amazed at the speeches made by the women. They were by far the most forceful and inspiring talks I heard. And when I saw how the men treated them every prejudice I had been harboring was overturned.” ( UnXld 163)

If Breaux did not quite recant her position, rancor had replaced the rhetoric of “dynamic woman power” within a decade. In Chameleon she would characterize Washington women as ‘jealous, sniping harpies’

“so constituted that they cannot bear to see one of their sisters, who has been on a par with them, suddenly elevated to a position of power over them.” (Jones)

6. Casting calls.

Many dishes Breaux describes in Favorite Recipes of a Famous Hostess bear a distinctive southern cast. ( UnXld 161-62) Many of them also betray a marked British influence. Others anticipate the 1950s fad for convenience food shortcuts while others still are eccentric enough to consider hers alone.

On the southern front she inferentially credits the influence of black cooks for her often improvisatory technique. Unfortunately the frankly unreconstructed language Breaux chose is offensive. Even so, the credit she gives is by no means grudging:

“in the deep South the good old southern cooks, many of them not knowing how to read or write, and who cooked entirely by taste and instinct, when asked for the recipes of their delectable concoctions have given this proverbial reply:”

To paraphrase the reply that Breaux provides in offensive dialect, the cooks would explain that they would take a little of this and a dash of that until they got the right taste; nothing more. (Breaux 1) Breaux’s stated “endeavor to give… the right proportions of ‘this and that’ to make otherwise dull dishes delicious,” however, itself frequently fails out of absentmindedness or oversight.

Most of the many instructions for cooking crab fail to indicate how much of it to use; not until seven pages after the first slew of them does Breaux provide the quantity, in the recipe for a decidedly English devil.

Foremost among the southern styles displayed by Favorite Recipes ; Louisianan, which is no surprise because that is where Breaux grew up. “There are,” as she insists, “certain fish dishes to be found to perfection chiefly in New Orleans.”

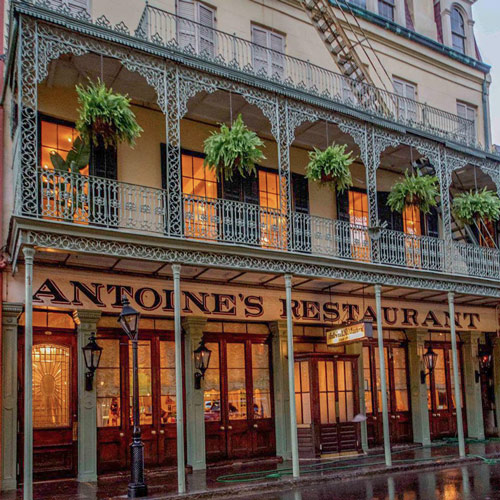

She likes Antoine’s in particular, where it remains possible to dine in the same elegant rooms she visited:

“The Bouillabaisse that Thackeray wrote so enthusiastically about as he found it in Marseilles, can be had today in as fine a form at Antoine’s noted restaurant in New Orleans; also Bisque d’ Ecrivesse, that can be had no where else that I know except in Paris, but there it will not be like Antoine’s. His pompano cooked in paper bags, and his oysters Rockefeller which is a dish he really invented. Then there is the way he serves little river shrimp, make a fish dinner at Antoine’s something to remember.” [sic] (Breaux 27)

Most of Breaux’s own Louisiana recipes are both eccentric and appealing. Her simple Creole Sauce for example omits onion from the usual trinity base also requiring celery and bell pepper that she includes along with nontraditional mushrooms, olives and Sherry. The gumbos go further, to the point of utter inauthenticity.

“Courtbouillon a la Creoles” looks at a glance like an arduous process. In fact the process takes little time; all the many ingredients, spiked with the allspice beloved of traditional Creole and English cooks alike, simply get tossed in the pot to boil together.

Other Creole preparations are elaborate. “Terrapin (Stewed)” relies on the complicated technique of the traditional turtle soup that originated in eighteenth century London and became the mandatory centerpiece of the annual Lord Mayor’s banquet. It also would become a fixture for fancy dinners throughout the Anglosphere until quite a way into the twentieth century. Today it has faded from favor except in its strongholds of New Orleans and Philadelphia.

7. British food in America.

It may seem something of a surprise that Breaux describes so many British dishes, but then cultural Anglophilia has persisted in certain social circles of both the south and neighboring District of Columbia. And in defiance of conventional wisdom John Folse has demonstrated how much traditional English practice inflects Louisiana cuisine. Even today the most elegant of Creole restaurants feature a bottle of Worcestershire along with the obligatory Tabasco.

Breaux describes a traditional English savory pudding as “Shrimp Pastys (or Pie, as it is called in Charleston, where several varieties of the pie are served).” Pasties themselves originate in Cornwall and also have become ubiquitous on the Upper Peninsula of Michigan where English miners arrived in the nineteenth century to ply their trade. This pudding is not a pasty either but by its overelaborate name remains an extremely good recipe that is deceptively simple to execute.

Shrimp paste, a traditional staple throughout the American south, is the recognizable descendant of English potted shrimp. Breaux describes a dead simple kedgeree and her default “Dinner in a Jiffy” for a small party of unexpected guests is a curry for shellfish or eggs based on white sauce. It could have been found in any number of nineteenth century English cookbooks.

Breaux also boils salmon in the English manner and inexplicably labels the English savory of oysters wrapped in bacon called Angels on Horseback as ‘pigs in blankets.’

8. Anticipating the craze for cans.

A base item useful to cooks and Andy Warhol.

Breaux opens her section on cooking soup with the advice not to cook it from scratch coupled with a command: “Make friends with Canned Varieties.” She does not advocate opening and heating a can alone but rather taking it as the base in place of long simmered stocks. “Today,” she contends,

“many brands of canned soup are delectable and it seems useless to go through the process of buying soup-bones, veal-knuckles, vegetable-‘bouquets’ and other ingredients, and the labor of simmering--or making the pot-au-feu for which France is noted…. ”

The claim of course is overbroad. Nothing, at all, stands as a substitute for long simmered stock but Breaux has a defensible enough point in terms of crash convenience, in part because she suggests combining different species of cans and embellishing them with other ingredients.

“Plain consommé,” for instance, “with a spoonful of sherry and a slice of lemon for each serving becomes a ‘company’ soup.” That is fair enough; even cutprice Campbell’s makes a more than acceptable consommé. (Breaux 11)

A better way to capitalize on canned consommé or stock would be to follow the lead of Jinx and Jefferson Morgan. The scallop soup from their Sugar Mill Caribbean Cookbook requires more ingredients but the same minimalist effort and may be the best of all shortcut recipes. It simmers chicken and beef stock with bottled clam juice and white Port to pour over the thinnest slices of raw scallops sprinkled with chives; alchemy.

The Morgans would have turned to their own slowly simmered stocks but the Sugar Mill recipe does not specify them and the canned kind is fine for cooking at home, especially now that bone broth is available almost everywhere.

Breaux also offers a serviceable weeknight shortcut that simply adds shellfish to larder goods; a cream of crab or shrimp soup built on a foundation of the cream of mushroom soup so beloved of community cookbook compilers as a base for sauces and casseroles.

She cooks fresh crab for her hybrid homemade and storebought soup but do not do that. Fresh crab is too precious for anything but the most respectful treatment. Under duress however it would be no crime to take some pasteurized or in a pinch even canned crab to fashion what can become larder based cream of crab.

Breaux dilutes the soup with milk and heats it while braising the cooked crab in a double boiler for about five minutes with some butter, a chopped small onion and black pepper before combining it with the soup, a teaspoon of Worcestershire and finally a Tablespoon of Sherry. As noted not at all bad. Her cream of shrimp is made the same way.

Despite her opening salvo, Breaux does not believe the can should be a cook’s only friend in the fraternity of soups. Those strange gumbo recipes involve no canned soup and neither do her instructions for the terrapin stew as well as equally English mock turtle and oxtail soups, species of slow food standbys she claims to suspect.

9. An imaginative eccentric.

Perhaps because Breaux had struggled to provide for her daughter after the death of her first husband, economy is a concern that recurs through the pages of Favorite Recipes . There are those recipes based on canned soup and some other innovations reminiscent of the mystery mousse prepared at Snaffles that became a sensation in later twentieth century Dublin. Like some of the Favorite soups it was not much more than a soup, canned consommé, combined with a couple of other humble ingredients to create something that tastes like a lot more than the sum of those parts.

Once again taking inspiration from New Orleans, Breaux returns to the Antoine’s kitchen. She decided to call her “favorite canapé” the “Calhoun Concoction.” It is, she explains,

“a simplified version of the very expensive ‘Paté d’ Antoine,’ made in imitation of the Strasbourg Paté, and almost equally expensive.” (Breaux 7)

Her ‘Concoction’ is not; Breaux simplifies the formula from Antoine’s and uses liverwurst instead of foie gras, buttermilk, lemon juice, Tabasco and Worcestershire, canned button mushrooms and sliced black olives instead of truffles. (Breaux 7-8)

The alternapaté “can be made in a few minutes and is,” Breaux thinks, “really more delicious and delicate than the expensive imitation of the Strasbourg Pâté.” (Breaux 7)

Try it the Breaux way.

With another innovative alternative, this time a technique, Breaux addresses the perennial problem of cooking a whole turkey without drying away the breast. She browns the bird all over in “hot grease” (no mincing words there) then seasoning it with salt, cayenne and black pepper (Breaux considers the sequence crucial; the emphasis is hers) and steams it until almost done before stuffing and roasting it “in an oven, not too hot” for an hour or so. She provides timing for the sequence based on the size of the bird and recommends lining the breast with bacon before placing it in the oven. (Breaux 101)

On the equally perennial debate whether or not to stuff a turkey, Breaux in common with Elisabeth Ayrton (and, for whatever it is worth, us at bfia) stands firmly in the Old School camp that unfortunately has fallen from favor: Stuffed turkey tastes best. A rich stuffing adds a layer of flavor to the turkey and as Mrs. Ayrton notes in The Cookery of England , the bird

“is inclined to be dry, so it must be well and richly stuffed, so that the fat from the stuffing works through from inside.” (Ayrton 182)

Breaux also is unequivocal on the issue: “Turkeys are most tender and juicy when stuffed with heavily seasoned, good, wet dressing.” And if the cook inexplicably eschews the bacon she must substitute thin slices of salt pork to keep the breast moist; just remember to remove it for the last half hour so the skin can brown. (Breaux 101)

Breaux treats domestic duck much the same way, but with a twist. She parboils it until tender, stuffs it and then shoves it into a hot oven just long enough to brown. She likes domestic duck well done but is adamant that its wild cousin

“should never be cooked other than as plain roast and, according to the epicures, should ‘fly through the fire’ -- in other words, it should be so rare that the blood almost follows the knife when it is carved.” (Breaux 103)

Exemplary advice all around. And finally to our title: “Never buy a dead lobster. He must be alive and kicking, or” Breaux warns, “he will kick you later.” (Breaux 40) Words for a cook to live or die by.

Sources:

Anon., “Wedding Bells in New Orleans: Miss Daisy Breaux Marries Mr. Andrew Simonds,” The New York Times (1 May 1885)

Elisabeth Ayrton, The Cookery of England (London 1974)

Daisy Breaux (Mrs. C.C. Calhoun), Favorite Recipes of a Famous Hostess (Washington DC 1945)

Oliver Herford, Sea Legs (Philadelphia 1931)

Mark Jones, “The Irrepressible Daisy Breaux,” Mark Jones Books , https://markjonesbooks.com/2016/01/14/the-irrepressible-daisy-breaux (14 January 2016) (accessed 23 December 2020)

Don Lindgren & Mark Germer, UnXld: American Cookbooks of Community & Place Volume One, Alabama-District of Columbia (Biddeford ME 2018)

Jinx & Jefferson Morgan, The Sugar Mill Caribbean Cookbook: Casual and Elegant Recipes Inspired by the Islands (Boston 1996)

Polytechnic Publishing Company, “From The Publisher:” Favorite Recipes of a Famous Hostess (Washington DC 1945)

Lamar Sparks, “‘The Autobiography of a Chameleon’ Gives Colorful Life of Mrs. Calhoun, With Interesting Atlanta Bearing,” The Atlanta Constitution (24 November 1930)

Elizabeth Swaim, “Owen Wister’s Roosevelt: A Case Study in Post-Production Censorship,” Studies in Biography Vol. 24 (1974) 290-93