An Appreciation of the anchovy, featuring E. S. Dallas, other lubricious subjects and embedded recipes.

An Appreciation of the anchovy, featuring E. S. Dallas, other lubricious subjects and embedded recipes.

Diligent readers of britishfoodinamerica will have noted that anchovies infiltrate a good proportion of traditional British recipes. They theoretically are available fresh from the fishmonger, and transportative charred whole over coals or blasted under a broiler, but at least in the United States the little fish can be hard to find. Fresh ones embody something of a paradox, for they are not only oily but also mild, even subtle, in flavor. This Appreciation, however, has nothing to do with them, for as our own Phoebe Dinsmore trenchantly observes of canned versus frozen versus fresh beans or peas, cured anchovies are an altogether distinct substance from their unprocessed cousins.

1. The Romans.

Since ancient times, anchovies have been preserved by salting or packing in oil to produce their characteristic tang. The Romans shipped them to Britain but unlike liquamen or garum, the fermentation of rotten fish guts beloved of the ancient conquerers, anchovies are no historical relic. Liquamen itself sounds pretty bad, but probably was in fact a useful seasoning; the fermented residue cannot have tasted that much different from the fish sauces ubiquitous to the cuisines of southeast Asia today.

Like fish sauce, cured anchovies actually are fermented, a fact happily unknown to virtually all American aficionados. This fact of fermentation itself gives anchovies their versatility, for as Calvin Schwabe explains, “[f]ermented fish products are remarkably compatible with other foods” and are relatively green or environmentally sound too: “For this reason, greater attention in America needs to be paid to traditional means of fish preservation other than freezing, such as fermentation.” (Unmentionable Cuisine 281)

2. The Cure.

On the off chance that you come into a boatload of fresh anchovies and you would like to help preserve the planet, Schwabe can tell you how to preserve the fish:

“Behead and gut them. Put a 3/16 inch layer of pure salt in the bottom of wooden cask or other suitable container and cover this with a layer of the fish arranged parallel to one another. Add another layer of salt, a second layer of fish at right angles to the first, and so on until the container is full. The top layer should be salt. Place a weighted wooden disc on top of the mixture.

After 2 or 3 days the fish will have sunk. Then add alternating layers of fish and salt to the top of the container so it is filled again. ‘Curing’ takes 6 to 7 months at room temperature during which time the water and fat will rise to the surface. You may add fresh 25-percent-strength brine if necessary to keep the fish well covered. After this the cured anchovies are ready to be repacked in small containers.” (Unmentionable Cuisine 281)

Wooden casks are not as thick on the ground as formerly, and while it is unclear what ‘other suitable container’ Schwabe contemplates, earthenware or something nonreactive would appear preferable to a shoebox or anything aluminum.

3. The British.

In any event, no cuisine, not even the Italian, has embraced the anchovy like the British, to the point where Maxime De La Falaise (aka McKendrick) has written that “[a]nchovies are as essential to English cooking as truffles are to the French.” (Seven Hundred Years 198) The stream of importation begun in Roman ships has continued apace for centuries, interrupted only and not even always by war. During the great conflict with the French spanning the long eighteenth century that culminated in 1815, for example, Nelson’s captains carried stores of anchovies to enliven the officers’ shipborne food. (Macdonald 128)

Somewhat curiously, neither Dorothy Hartley’s Food in England nor Traditional Foods of Britain by Catharine Brown and Laura Mason includes an entry for ‘anchovy,’ although its absence might be explained by those authors’ emphasis on foodstuffs of geographical origin in the British Isles.

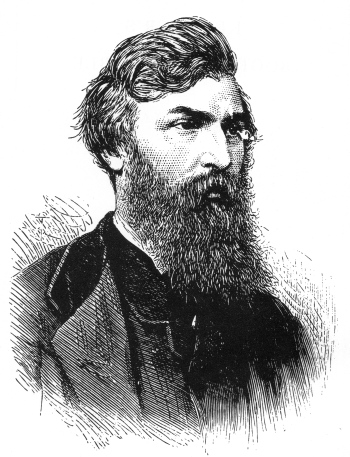

‘Anchovy’ does, however, merit an entry in Kettner’s Book of the Table, which first appeared in London during 1877 and took its name from the famous restauranteur. The anonymous author, E. S. Dallas, was a published literary critic who also wrote leading reviews and obituaries of the great and the good for over a decade in The Times (also anonymously, in compliance with the paper’s practice at the time). He knew Dickens, Landseer, Rossetti, both Ruskins and other luminaries. We do not know whether he knew Sir Henry Thompson, but one acquaintance wrote of Dallas that “I never, I think, saw such strong, perceptive qualities except in the portrait of Hazlitt” and, like Hazlitt, he endured a scandalous divorce. Again like Hazlitt, Dallas’ strong and indiscriminate libido probably contributed to his early demise, at fifty-one. (Kettner’s Book vi) Rossetti wrote, demonstrating that he was a better painter than poet,

“Poor old Dallas!

All along of his phallus,

Must he come to the gallows?” (Kettner’s Book x)

Dallas himself was an enthusiast of the cured anchovy as well as the connubial bed:

“Dr. Badham says, with perfect truth, that the anchovy ‘was to the ancient world what the herring is to the modern--compensating in some degree for its inferiority to the last while fresh by surpassing when cured the very herring itself as a relish; and furnishing the materials for the finest fish sauce either on record or in use.’” (Kettner’s Book 29)

Kettner’s restaurant remains in business at its original Soho location; Champagne still features prominently there, and many dishes do include anchovies, if mostly at a discreet remove rather than as the showcase ingredient. That is appropriate, because by tradition, British recipes use the anchovy to ratchet up the flavor of other ingredients rather than featuring it as the focus of a dish. Anchovies even have found their way into curry paste, in a recipe for curried prawns with pears from The Sporting Wife, a 1971 imprint.

In The River Cottage Fish Book, Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall displays a typically English sentiment in writing “[a]ll hail the anchovy, without whose intense piquancy--sheer essence of fish--some of the recipes in this book would fail to reach the dizzy heights we expect of them.” (Fish 347) We do, however, take issue with Fearnley-Whittingstall on a minor point. Those ‘dizzying heights’ result not from ‘essence of fish’ but rather from something else, the alchemical collision of the fermented fish with other flavors. As Bee Wilson has noted in The Telegraph,

“[s]lipping a few anchovies into a beef stew has long been a trick of clever cooks. The fish melts away, leaving only a meaty depth. It is particularly satisfying serving this to people who proclaim themselves anchovy haters. They are usually the ones who ask for second helpings.” (“Kitchen Thinker”)

As with many things, Jane Grigson wisely noted over three decades ago how anchovies played a starring role in English kitchens and why:

“Anchovies unfortunately are not a northern fish. Our experience of them always has been of the salted kind. Anchovies were and are an important relish in our food and cooking…. I find anchovies useful in meat cookery to liven a beef stew or casseroled pigeons. They dissolve so perfectly that they are unidentifiable, their sharp piquancy blends well into the sauce.” (English Food 123)

Why this should be the case may come down to chemistry:

“It turns out there is good science behind this little wheeze. Beef is rich in the savoury ‘fifth taste’ known as umami, also found in parmesan, Marmite, tomatoes and mushrooms. The meatiness of beef comes from a group of amino acids called glutamates. Anchovies, meanwhile, are rich in another savoury chemical compound: inosinate. Japanese scientists found that inosinate heightens the savoury taste of glutamate many times: the two work in synergy. In layman’s terms, those anchovies take your beef casserole from merely meaty to seriously flavoursome. (“Kitchen Thinker”)

Nonetheless we at britishfoodinamerica would like to cling to magic as the cause of the Anchovy Effect.

Many Americans would be discomfited to learn that anchovies, or the inferior anchovy paste made from the lesser specimens of the catch, are virtually omnipresent in the savory dishes produced by restaurant kitchens. Because of this role as a supporting, or perhaps character, actor, Americans also tend to be unaware either of the historical importance of the anchovy trade to Britain or that the cured fish is ubiquitous to British food.

The first recipe that Karen Hess discusses in her impeccably annotated Martha Washington’s Booke of Cookery (New York 1981) is a mutton stew flavored with anchovy and other bedrock English seasonings. As she explains, the “Booke of Cookery could hardly open with a more appropriate recipe; the use of nutmeg, lemon peel, anchovy and wine vinegar to season stewed mutton, with butter stirred in at the end as the only liaison, makes this dish a fine example of English cookery in the opening years of the seventeenth century.” (Martha Washington’s Booke 39)

Hannah Glasse and Mrs. Raffald at mideighteenth century, and Eliza Acton at midnineteenth, are but two examples of particularly significant writers who seasoned many of their foods from both land and sea with anchovies as well.

Anchovies remain an essential component of many British dishes, including Melton Mowbray pork pies, one of the great pleasures of any cuisine. Their presence in this archetypal raised pie enhances the flavor of the pork rather than introducing a fishy tone. The same subtlety infuses roast leg of lamb studded with anchovies, instead of or along with garlic, a tradition in Britain as well as France and Italy. Similarly, Scotch woodcock is a play on words kindred to Welsh rabbit that marries anchovies with butter, cayenne, cream and egg yolks for service on toast as a traditional savory.

As britishfoodinamerica noted in our ninth, ‘Double Summer Number,’ compound butters represent a cornerstone of British seasoning, and anchovy butter, for finfish but also for steaks and chops of both lamb and pork, may be the most characteristically British of them all. As an incidental bonus, anchovy butter is fast and foolproof; all you need to do is mash together equal amounts, more or less in proportion to taste, of anchovies and unsalted butter, although E. S. Dallas maintains that “Anchovy Butter is made with any quantity of butter from half an ounce to an ounce for each anchovy. The half-ounce scale is the best for ordinary use.” (Kettner’s Book 29) (Slightly) longer recipes also abound.

4. The Entrepreneurs.

Between Mrs. Glasse and Miss Acton, in 1828, an entrepreneur called John Osborn created The Gentleman’s Relish, or Patum Peperium (this last, roughly ‘pepper paste’), essentially a thick anchovy butter flavored with herbs and spice. The Relish traditionally finds its way onto thin buttered toast, either alone, or, better, with cucumber or, best, with mustard and watercress, but, as the packaging warns the consumer, “[t]o appreciate the proper flavour of The Gentleman’s Relish, it should be used VERY SPARINGLY” (flamboyant emphasis in original). As all of this should indicate, The Gentleman’s Relish remains available in Britain, made to the ‘original 1828 recipe’ and sold in irresistible little white plastic pots whose afterlife is handy for the storage of leftover ground spice mixtures.

Dallas includes a recipe for something similar styled an ‘essence’ in Kettner’s Book of the Table, and Miss De La Falaise has one in Seven Hundred Years of English Cookery. Neither is at all difficult to make and each would be a welcome addition, alongside the cans and jars of indispensable anchovies, to your larder.

In a different but also simple and buttery mix, our own Curmudgeonly Raconteur simmers together roughly equal amounts of anchovy, garlic and unsalted butter for dipping crusty bread. The result is addictive, as pleasing to the palate as it is unpretty and anaphrodisiac.

On the aphrodisiac front, a form of assistance unnecessary for our tragic friend Dallas, The Gentleman’s Relish is sufficiently famous in Britain to have become an ironic reference point for other products. In 1979, Ronnie Barker, the rather unfunny comedian, published a book of captioned drawings and photographs of nude women under that title (and subtitle “A Saucy Look at the Fairer Sex”). Coco de Mere, the elegantly exorbitant English purveyor of sex toys and lascivious items, markets a personal lubricant variously as ‘The Gentleman’s Relish’ and ‘Polished Talent,’ but, at $27 a small bottle, it remains an unknown quantity to the Editor. It does sport an amusing label with three thrusting images that emphatically are not, as at first they seem, the curled feathers in the escutcheon of the Prince of Wales.

5. The savouries and sauces.

Back in the kitchen, Mrs. Raffald also included savories that featured the anchovy, for as Mrs. Grigson also notes, a “main role” of the fermented fish in Britain “has been as an identifiable relish, to stimulate appetite and thirst…. ” (English Cookery 123) She cites several such stimulants, including one of Mrs. Raffald’s from 1769 that tops buttered toast with a layer of anchovies, tops the fish in turn with a mixture of grated cheese and minced parsley followed by melted butter. The assembly goes under the broiler until golden brown; irresistible, especially with a pint of bitter ale.

Cured anchovies also are foundational ingredients for prepared seasonings including Worcestershire (in its case along with tamarind) and King of Oudh (from Fortnum’s) sauces, and for many of the other bottled condiments that have proliferated over the years on British grocery shelves, particularly during their Edwardian apotheosis but also into our own time. As Karen Hess noted not so long ago in historical terms, “anchovy is an important ingredient of most bottled sauces that are heavily used in both English and American kitchens.” (Martha Washington’s Booke 40) Edwardian options, sadly lost to us today, included British Lion, Empress of India, Harvey’s, Lazenby’s, Mandarin and Nabob’s.

Pass the Lazenby’s, please.

Many of these products dated from the eighteenth century and, according to Elizabeth David, “reflected the selling power of an Imperial association.” David adds that “Yorkshire relish, Clarence sauce, Dr Kitchener’s salad cream, Burgess’ Anchovy Essence (the firm of Burgess had been established in 1760), and Elizabeth Lazenby’s range of sauces (Harvey’s was among them) were all popular in the late Victorian era.” (Spices, Salt 12)

George Watkins, a company in Kent, still produces a survivor from the Great Age of British Bottled Sauces, its Anchovy Sauce, a mixture of anchovy, salt, and spice diluted with water. It it hard to find but handy for boosting the flavor of soups and stews.

Quick homemade sauces that add anchovies to the debris and juices of a skillet lift the flavor of steaks and chops at least as well as their bottled counterparts. All you need are a couple of anchovies and a medium to deglaze the pan; a little flour and some stock, shallots or garlic followed by tomatoes, or a few slices of mushroom and some sherry.

When you next grill a steak or chop, or cook an authentically British braise of beef or build a raised pork pie, follow the eighteenth century lead of Hannah Glasse and her readers: Reach for the anchovies.

Fresh anchovies never appear on the menu at Bridge restaurant in Westerly, Rhode Island, and always feature as a daily special.

Recipes that benefit from anchovies appear in the practical.

Sources:

Catharine Brown & Laura Mason, Traditional Foods of Britain (Totnes, Devon 1999)

E. S. Dallas, Kettner’s Book of the Table (London 1877)

Elizabeth David, Spices, Salt and Aromatics in the English Kitchen (London 1970)

Maxine De La Falaise, Seven Hundred Years of English Cooking (New York 1973)

Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall, The River Cottage Fish Book (London 2007)

Jane Grigson, English Food (London 1974)

Barbara Hargreaves, The Sporting Wife: A Guide to Game and Fish Cooking (London 1971)

Dorothy Hartley, Food in England (London 1954)

Karen Hess, Martha Washington’s Booke of Cookery (New York 1981)

Janet Macdonald, Feeding Nelson’s Navy: The True Story of Food at Sea in the Georgian Era (London 2004)

Calvin Schwabe, Unmentionable Cuisine (Charlottesville 1999)

Bee Wilson, “The Kitchen Thinker: anchovies,” The Telegraph (19 February 2010)