Pudding: A Global History by Jeri Quinzio

(or, they published that?), with a reluctant Appreciation of Sir Benjamin Thompson, Reichsgraf von Rumford, and a digression concerning Robert May.

1. The importance of pudding.

It is inexcusable that the Editor overlooked the 2012 publication of Pudding on several grounds. The book is not obscure, at least not in the world of culinary literature. As part of “The Edible Series” from Reaktion Press it joins some thirty previously published monographs that address a single food, including subjects broad (like Curry or Spices) and as narrow as Dates. A number of notable food writers, including Bee Wilson (The Sandwich) have contributed to the series, and critics from publications as reputable (or not, depending on your political proclivities) as the Chicago Tribune and The Wall Street Journal demonstrate a predisposition to praise the books within it.

In historical terms, the multiple manifestations of pudding may be the most important British culinary technique. People think of roast beef, fish & chips, steak & kidney pie, high tea, trifle or even chicken tikka masala as competitors for the status of British icon, but pudding beat them all for ubiquity at least until after the turn of the twentieth century.  Furthermore, popular imagination commonly pairs the beef with Yorkshire pudding while steak & kidney fills puddings as well as pies. Quinzio herself makes the (somewhat feeble) case that trifle itself is a form of pudding. The subject should not have been stealthy enough to elude the radar of the Editor.

Furthermore, popular imagination commonly pairs the beef with Yorkshire pudding while steak & kidney fills puddings as well as pies. Quinzio herself makes the (somewhat feeble) case that trifle itself is a form of pudding. The subject should not have been stealthy enough to elude the radar of the Editor.

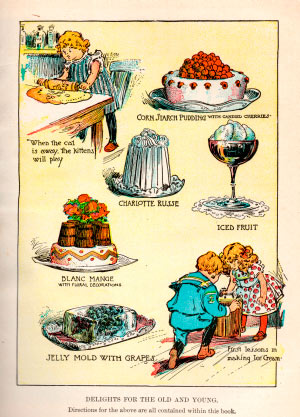

For the purposes of Pudding, and for that matter our own, the term denotes a pastry, filled or rolled or plain, which is boiled or steamed in a cloth, bag or basin. All manner of desserts may be mislabeled pudding in Britain, but the broader usage is confusing and has begun to fade.

Despite its favorable press, “The Edible Series” is in fact uneven, and if the title of this essay hardly contains Whitmanesque multitudes, it does hold a double meaning, for Pudding is a bad book. The prose is bad, what passes for historical analysis is bad, the omissions are bad; even the editing is bad.

2. Too hasty a take on both a hasty pudding and a complex character.

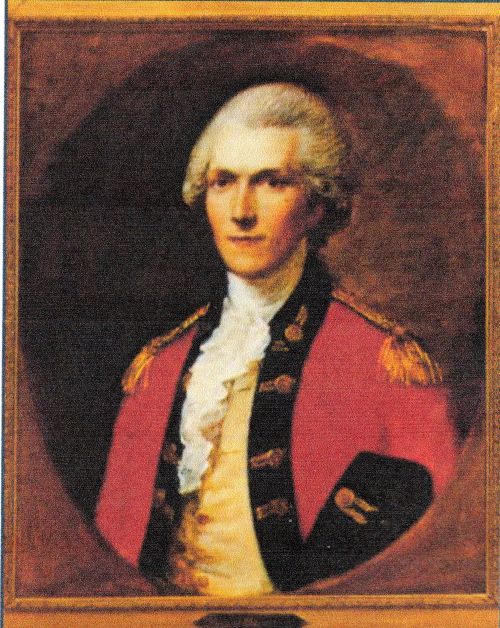

Take for example the discussion of Benjamin Thompson, a Loyalist who fled revolutionary America. Even by the standard of eighteenth-century Anglo-American elites, Thompson was a complicated and contradictory figure. “Scientist, inventor, innovator, spy, soldier of fortune,” he was “admired, despised, honored, vilified--Benjamin Thompson, a New Englander by birth.” (King 1)

Quinzio fails to do him justice. She does disclose that Thompson was “famed for his many inventions and innovations including a portable field kitchen and a coffee percolator,” that he became a Fellow of the Royal Society and a count “for his services to Bavaria,” but she overlooks the basis for his fame and unfairly tars him a ‘parsimonious reformer.’ (Quinzio 75, 123)

After placing Thompson in a subchapter called “Hasty Pudding in America,” Quinzio proceeds to describe his attempt while in England to promote the pudding as frugal food for the poor. (Quinzio 73, 75) She finds it “surprising that Benjamin Thompson (later known as Count Rumford)… recommended hasty pudding to the English” because it had become “a symbol of American independence.” Her basis for this last assertion is the description of Captain Gooding’s men “as thick as hasty pudding” in the song ‘Yankee Doodle.’

Notwithstanding her linkage of hasty pudding to the American Revolution, Quinzio is incredulous that Thompson later described the dish and promoted a recipe for it in Britain, although she overlooks the fact that it appeared along with many other economical dishes in a lengthy series of recipes he had written: “Despite the fact that the English had been making hasty pudding for hundreds of years, albeit with different grains, he defined the pudding and described it in meticulous detail.” (Quinzio 75) That, however, is what cookery writers do, and Quinzio includes a recipe for hasty pudding in her own book.

As with all his recipes, “he describes all the processes in minute detail.” Incidentally this was written over three decades before Quinzio, so it appears she has cribbed the phrase without attribution. In any event, Thompson was a windbag and bore, in conversation and on the page, who never found the discipline to resist beating a dead horse, so his instructions border on ridiculous. The hasty pudding recipe itself includes two pages on how to eat it, “by regular advances, in order not to demolish too soon the excavation which forms the reservoir for the sauce.” (quoted by Brown 160)

If the hasty pudding that Thompson advocated as food for the poor was so common, then why, as Quinzio asserts, was it the case that his “advice was not followed”? Again according to Quinzio herself, “[f]ew recipes for hasty pudding were included in nineteenth-century English cookbooks. Eliza Acton had none; nor did Isabella Beeton.” (Quinzio 76)

Those “different grains” that Quinzio sidesteps provide the key to understanding Thompson’s advocacy. Unlike earlier hasty puddings, by the middle of the eighteenth century the New England offshoot had become based on cornmeal, known to the British as maize or Indian meal, and that was something they fed  to pigs, not people. Thompson therefore had some convincing to do, and some explaining too.

to pigs, not people. Thompson therefore had some convincing to do, and some explaining too.

He led with the sales job, arguing that hasty pudding was “the most advantageous method of using Indian corn as food… particularly when it is employed for feeding the poor, a dish made of it that is in the highest estimation throughout America, and which is really very good and very nourishing.” (Thompson quoted at Herman 256) There follows, logically enough, the meticulous description of a recipe that unaccountably puzzles Quinzio.

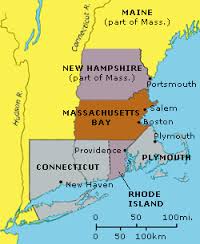

She also states that Thompson took the name Rumford for his Holy Roman Empire title (that, in fact, is what it was) from the New Hampshire town “where he had once taught.” (Quinzio 75) That is like saying the RAF Hurricane was named for a lantern. Rumford (now Concord) was where Thompson, the son of subsistence farmers, had married a wealthy widow fourteen years his senior. She had cultivated connections with the royal governor of New Hampshire, and through his wife Thompson acquired the fortune and major’s commission in the colonial militia that would allow him to begin a rocky ascent into high society; his commission itself infuriated aggrieved veterans of the French and Indian War more qualified for the sinecure.

3. Spy vs. Spy.

Thompson lost the widow’s stake when he fled within the British lines at Boston to avoid tar and feathers, abandoning her and their small daughter; Thompson would never see his first spouse again, and treated their child badly when she joined him in Europe years later. He retained his contacts with the governor and his Tory circle, however, which gave him access to the upper echelon of the British military and political administrations in North America.

Thompson promptly began to engage in espionage for the crown. An affair with Mary, the promiscuous wife of Isaiah Thomas, gave him a splendid source of information about rebel plans. Thomas printed the most radical newspaper in Boston, The Massachusetts Spy, and met frequently at home with “the inner circle of revolutionaries” that included Paul Revere and Joseph Warren. Mrs. Thomas showed no compunction about eavesdropping to reveal the substance of their long conversations to Thompson, both before and after her aggrieved husband caught the lovers in flagrante. (Brown 35-36)

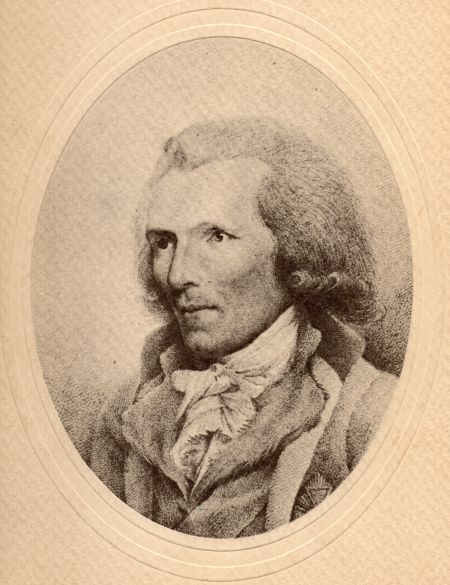

Count Rumford, spy

The patriot party justifiably suspected Thompson of treachery and placed him under surveillance, so he commenced communicating with his spymasters by correspondence instead of in person. These letters used disappearing ink and a numerical code: Thompson wrote “the first secret-ink letter of the American revolution.” (Brown ix)

According to Sanford Brown, who published a nuanced and fascinating biography of Thompson in 1979 after some four decades of research, “[t]he technological sophistication of the secret-ink letter was very good.” The visible covering letter alternated lines with the encoded invisible ink that Thompson made from nutgall, “an excrescence on young twigs of oaks produced by insect eggs deposited on or under the surface of the bark.” (Brown 37-38)

Brown, no slouch himself in the espionage racket, reports that the sophistication of the code matched the ink derived from bugshit. During the Second World War, he ran a counterintelligence laboratory at MIT, but even so needed to enlist assistance in cracking the British cipher system. He explains:

“A World War II-trained cryptographic expert was free between jobs to spend a month unraveling the technicalities of eighteenth-century numerical spy codes…. Without his reconstruction of the two relevant code books, my study of the count would have been incomplete.” (Brown ix)

4. Fort Golgotha.

Thompson sailed to London in 1776 and wangled an introduction to George Germain, Lord Sackville, who had become secretary of state for the North American colonies during the previous year. He became a great patron of Thompson, who eventually rose to become one of his two undersecretaries of state before obtaining a lieutenant colonel’s commission in the British army.

In 1781, Thompson sailed for North America commanding a regiment of the King’s American Dragoons but he and his carabiniers arrived too late to see significant action. They did, however, make a certain mark. Sir John Thomas, master of Peterhouse, Cambridge, has described Thompson’s “conduct and general behaviour in his native land [ ]as nothing short of despicable.” (Thomas 13) While garrisoning Huntington on Long Island in New York during the winter of 1782-83, “Col. Thompson’s Regt. Of Horse… live[d] upon the Inhabitants as they please[d], and commit[ed] the greatest acts of Violence” according to the report of an American spy. (Brown 88)

These activities included the theft of horses for presentation as gifts to his superiors, the ‘requisition’ of rations, demolition of the local church, destruction of an apple orchard and confiscation of 3,500 fence rails. Thompson used the lumber to construct fortifications for his encampment on the footprint of the church, a lovely gesture of disdain and desecration. He built his redoubt with the slave labor of every able man in town.

Thompson pitched his luxurious headquarters (attended by two English servants and a black groom) over the grave of Ebenezer Prime, a patriot preacher who had built the ill-fated church, so that he “might tred on the d---d old rebel’s head whenever he went in and out of his tent.” (Brown 88)

The rest of the Huntington graveyard was put to more practical use. Thompson ordered the gravestones cut into tables, fireplaces and ovens. His troops taunted the townspeople with gifts of bread bearing the inscriptions that described dead relatives baked into the crust. To its populace, Huntington had become “Fort Golgotha.” (Brown 88)

All this occurred after the otherwise widespread cessation of hostilities following the fall of the British fortress at Yorktown and preliminary execution of a peace treaty between the combatants.

Thompson by no means dispensed ruthless cruelty to the ‘enemy’ alone. He not only shot deserters on sight but also carried their corpses within regimental carts “conspicuously labeled” for the purpose. (Brown 88)

5. Politics sexual and combustible.

5. Politics sexual and combustible.

Back in London, he requested and, somehow, obtained promotion to colonel with a lifetime pension for these services to the crown.

Thompson and Germain were rumored to be lovers, and the idiosyncratic, not to say bizarre, Varick Vanardy, Jr., claims that Thompson “was a gay genius” whose many liaisons with women amounted only to platonic camouflage. (Vanardy 7) Notwithstanding the limitations of his research, or maybe consistent with them, Vanardy is not alone; the house where Thompson was born in Woburn, Massachusetts, is a stop on the gay freedom trail in metropolitan Boston.

Brown notes that Thompson’s fellow exile, the former Massachusetts governor Thomas Hutchinson, was “astonished” at the open discussion of “shocking” behavior between Thompson and Germain. Brown goes on to explain that

“ ….Lord George was considered to be a homosexual…. On more than one occasion Thompson’s name was associated with Germain’s in this regard. This should be borne in mind when we see later the tremendous hold that Thompson had on Lord George when he needed favors done for himself.” (Brown 51)

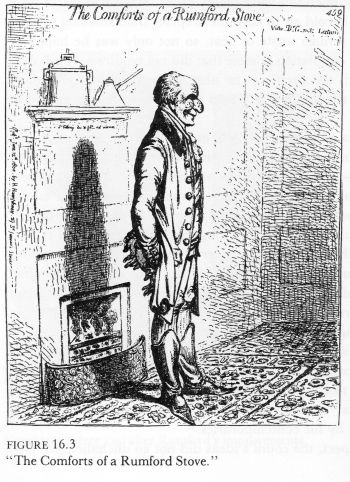

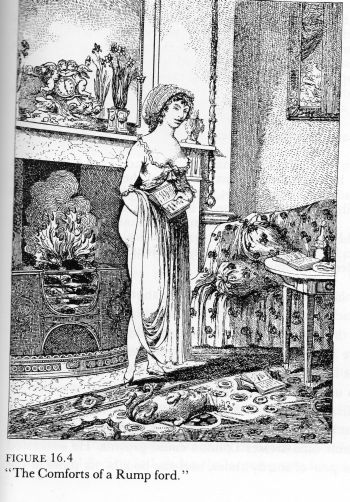

Gillray, who missed not a satirical (or satyrical) trick in print, drew Thompson backed up bare-assed in front of one of his many important inventions, the efficient fireplace that he developed between 1796 an 1798.

The Rumford Fireplace revolutionized heating in Georgian buildings. Thompson, or Rumford as he then styled himself, gave the fireplace a smaller, shallower bay, an angled coving and “streamlined throat” to provide better draft than the big traditional hearths. Two months from the start of production Thompson had supervised the installation of more than 250 of his fireplaces in London alone; two years later, by the end of the century, it had become state of the art throughout the western world. (Buckley Rumford Fireplaces 1) The pattern is still manufactured, in both the US and UK, and still bears his name.

Like anything else involving Thompson, his profits from the fireplace aroused controversy. A number of critics claimed that Thompson had merely introduced a design common enough in his native New England to the United Kingdom, or had stolen the concept from another.

Thompson married more than once, fathered children and kept “various mistresses” all his life, some simultaneously, and carried on a lengthy correspondence with one of the most famous, Lady Palmerston. In response to an explicit inquiry from her, Thompson disclosed that he had not yet slept with the newlywed teenage wife of the septuagenarian Elector of Bavaria. Whether or not Thompson eventually succeeded on that front, he did have an illegitimate daughter with one of the Electoral mistresses, whose sister he also seduced. (Brown 53, 249, 156, 102; Thomas 16)

None of this is dispositive, but it appears more than likely that the intrigue of the bedroom and the mechanics of sex were simply weapons in Thompson’s arsenal of ambition. They--both ambition and arsenal--were prodigious, and backed by an intellect astonishing for both its talent and allegiant adaptability.

Cruikshank also catches the eros of efficiency

6. On to Munich.

The Elector whose youthful bride Thompson considered seducing was his friend and patron, Carl Theodor of Bavaria, the man who created him count. Thompson did not profit from their initial acquaintance.

The newly-created colonel had crossed the Channel to try his hand as a mercenary after returning to England from America. Inexperience did not deter Thompson from touting his military prowess and, improbably, his exaggerations induced the Elector to offer him the post of adjutant general in the army. At the time Bavaria was poor and the state supported only an underfinanced, ramshackle force focused on enriching its officers rather than martial prowess. Thompson did not consider the position much of a prize so he determined to try his luck somewhere more promising.

Not much time would pass before Thompson met an elderly Viennese noblewoman whom, he wrote in a Delphic turn, “opened my eyes to other kinds of glory than that of victory in battle.” As a result of this acquaintance, Thompson claimed with no small exaggeration that he had determined to devote his efforts to the welfare of humanity. (King 3 quoting ‘Larsen’ 48)

Thompson never could resist a shot at the main chance and his colder eye would ensure that he did well by doing good. He took the Elector’s offer, either because of his encounter in Vienna or his failure to secure a better position, but only after negotiating an inventive agreement that would ensure his enrichment if any of his work benefited the principality.

Apparently oblivious to the irony inherent in beginning his eleemosynary career as a high officer, Thompson padded his payroll further as a covert operative, first for the British against his new sponsor and then against them for the French; his former colleagues took to keeping tabs on him through “the excellent British spy ring in Munich.” (Brown 140-41; Thomas 14)

The circumstances of Thompson’s ennoblement embody the contradictions of his life, for the services he rendered to the Bavarian principality were as significant as his greed and his betrayals.

Thompson reorganized the Bavarian army, streamlined its procurement practices and instituted a humanely innovative policy, off-duty work at extra pay for otherwise idle soldiers. Among other things, he established ‘military gardens’ for tillage by the troops. The gardens would ensure better nutrition for them. It was Thompson who introduced the turnip and potato, which would become enduring Bavarian staples, into southern Germany. (Brown 121; King 3)

In a series of other offices, Thompson encouraged the planting of gardens more generally, introduced crop rotation and designed, then oversaw creation of, the famed 600 acre English Garden that still survives. His energies also resulted in the foundation of cottage industries, free schools for poor children, industrial academies, and a veterinary college to breed cattle and conduct research about the most fattening livestock feeds. (King 3)

He did not, however, do anything that enabled the army to conduct military operations.

At the height of his power Thompson held simultaneous appointments as adjutant general, chamberlain of the court, chief of the general staff, chief of state, lieutenant general, minister of police, minister of war, privy counselor and treasurer. He drew a salary for each position and the Elector also granted him a lifetime pension. (Thomas 16; Brown 140) Under any sovereign but Carl Theodor, Thompson would have been an idiosyncratic choice to fill these offices, particularly the military posts.

The partnership worked because the two tyrants shared a cynical and despotic disposition. The Elector pursued “ultra-conservative” policies that favored an obscurantist Catholic establishment (the clergy constituted as many as one in fifty inhabitants of Munich), cut the budget of the secular Bavarian Academy and established a College of Censorship. Thompson’s policies per se were driven by no particular philosophy--his goal was to please Carl Theodor and keep his own emoluments coming--but he applauded every antirational, autocratic move. (Brown 99-100, 142)

Thompson harbored an abiding fear of ‘popular Phrenzy.’ During the 1770s he had decried the ‘levelism’ of revolutionary Americans, and the great naturalist and zoologist Georges Cuvier claimed in later years that Thompson’s

Thompson harbored an abiding fear of ‘popular Phrenzy.’ During the 1770s he had decried the ‘levelism’ of revolutionary Americans, and the great naturalist and zoologist Georges Cuvier claimed in later years that Thompson’s

“views of slavery were the same as a plantation owner. He regarded the government of China as coming closest to perfection, because in giving over the people to the absolute control of their intelligent men alone… , it made, so to speak, so many millions of arms the passive organs of the will of a few sound heads.” (Brown 100, quoting Cuvier)

Carl Theodor himself had no great attachment to his principality and was not even Bavarian. He hated Munich and attempted to ‘swap’ the throne of Belgium for Bavaria with the Austrians. Throughout his reign, and even as the armies of Austria, France and Prussia marched at will through his adopted country, the Elector

“remained firmly convinced that his long-range interests were best served by intrigue, bribery, and passivity, and in this Rumford was his chief disciple. As the policy of noninvolvement threatened to pull Bavaria inexorably toward invasion and even annihilation, Thompson exercised the army in building military gardens instead of engaging in war maneuvers, and the elector promoted him to lieutenant general. When General Thompson concentrated the whole effort of his army on rounding up thousands of tramps, drifters, and beggars instead of following the suit of the neighboring states which were hardening their troops by border raids and foreign skirmishes, the elector made him his chief of staff and head of his war council. When he poured the whole of the country’s war budget into the English Garden in Munich instead of into guns, cannon, and powder, he was elevated to privy counselor, treasurer, and finally count of the Holy Roman Empire.” (Brown 142)

The elevation itself was a historical fluke, another instance of Thompson’s eerie good fortune. It resulted from a rare, five month interregnum between Holy Roman Emperors. Rebuffed in his effort to replace the dead emperor, Carl Theodor did manage to secure the temporary position of vicar, a sort of regency with extremely limited powers. One of them was the discretion to ennoble friends and cronies, and Thompson fit the bill. (Brown 141-42)

Yet he could not resist helping himself to the till, and his propensity for embezzlement was notorious even by the standard of an embezzling age. Accusations of mismanagement and self-dealing, more than likely true, dogged Thompson “and he reacted in a most vindictive manner to those who opposed him.” (Brown 140) All of this made him an even more convenient target to take the fall for Carl Theodor’s appeasement policy when the French revolutionary armies poured into the adjacent Rhineland.

Unlike Thompson, a knight who had not yet fallen from favor in England, or Carl Theodor, a Palatine duke, the Bavarian nobility had nowhere else to go and determined at last to take a stab at defending their lands.

Eventually, perhaps inevitably, Thompson had pursued too many cynical policies, alienated too many rivals, fallen afoul of various factions at the Bavarian court and fled to England.

7. The nature of heat and the uses of friction.

“It sometimes happens that an experiment that is simple, direct, and easily understood is performed just at the right moment in the development of a theory to become an immediate classic.” (Brown 198) The confluence of luck and skill, of timing and insight, recurred throughout Thompson’s life. In this case, Brown is describing the count’s most famous experiment, which enabled him to debunk the conventional wisdom, under fierce debate at the time, that heat was a material substance.

By drilling the bores of cannon in a water bath at various speeds and under various conditions, Thompson could record the time it took for the heat from the process to bring the water in the bath to a boil. He conducted the experiments before observers, in sound scientific style, and recorded their reaction. The heat was generated solely by the friction of drill against gun, to

“ ….the surprise and astonishment expressed in the countenances of the by-standers, on seeing so large a quantity of cold water heated, and actually made to boil, without any fire.” (Brown 197 quoting Thompson)

If Thompson the showman enjoyed astonishing his audience, Thompson the culinary didact had no intent to deceive them. The spectacle of the experiment did not render it practical; the application of friction was inefficient for “cooking victuals” and it would be better to boil water even by resort to burning fodder for the horses. (Brown 197)

The experiments indicated that the water always boiled after the same duration and the generation of heat by the drilling process did not dissipate over time. Because the amount of heat generated remained constant, and “appeared evidently to be inexhaustible” it could not be a material capable of dissipation. (Brown 198 quoting Thompson)

Heat had to be something evanescent. Thompson had confirmed its actual nature:

“ ….[A]nything which any insulated body, or system of bodies, can continue to furnish without limitation, cannot possibly be a material substance, and it appears to me to be extremely difficult, if not quite impossible, to form any distinct idea of any thing, capable of being excited or communicated in the manner the Heat was excited and communicated in these experiments, except it be MOTION.” (Brown 198 quoting Thompson)

At the outset of 1798 Thompson’s description of the experiment and his conclusion from it was read to the Royal Society. The society immediately published the recitation in its Philosophical Transactions as “Source of Heat excited by Friction.” The article, one of over sixty Thompson published throughout his life, created an international sensation. The findings were translated into French and German, and appeared in the press throughout Europe. Controversy, in this case by no means the fault of Thompson, erupted as the ‘materialists’ counterattacked. Even though some of his conclusions have proven flawed, the basic insight that heat is immaterial motion was sound.

At the outset of 1798 Thompson’s description of the experiment and his conclusion from it was read to the Royal Society. The society immediately published the recitation in its Philosophical Transactions as “Source of Heat excited by Friction.” The article, one of over sixty Thompson published throughout his life, created an international sensation. The findings were translated into French and German, and appeared in the press throughout Europe. Controversy, in this case by no means the fault of Thompson, erupted as the ‘materialists’ counterattacked. Even though some of his conclusions have proven flawed, the basic insight that heat is immaterial motion was sound.

8. A student of the stove.

During his sojourn in Munich, Thompson had conducted the experiments that led to his fireplace but they and the gunnery trials, as indicated by his aside about the efficiency of fuels for cooking ‘victuals,’ were not the only subjects that engaged his attention. “He was fascinated by the whole technology of cooking. Indeed, many regard him as the founding father of domestic and culinary science” (Thomas 14), not so different in terms both of vocational interest and self-aggrandizing behavior from Martha Stewart.

While ‘vacationing’ in Verona to sit out a particularly nasty round of court intrigue he revolutionized kitchen design. Thompson measured the flue temperatures that emanated from fires of differing sizes and experimented with placement of the fires at various distances from pots.

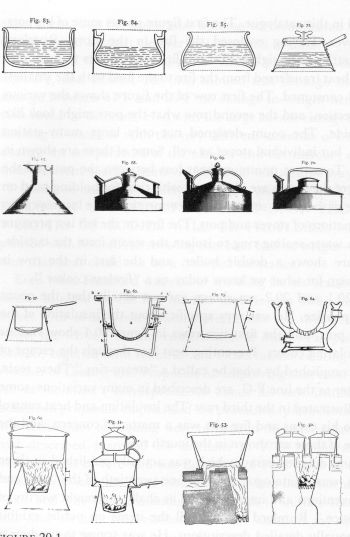

He concluded that smaller fires sent less heat up a flue and direct contact with flame produced the highest heat on the surface of a pot. His institutional kitchens therefore incorporated a series of smaller fires instead of a few big ones and featured sunken frames to allow the lowering of pots directly onto fires burning beneath various grates. Each fire could be adjusted by its own register and Thompson hit upon the novel idea of placing all the recessed fires within an insulated box for further efficiency.  He published his conclusions in his usual “pompous and didactic” style with a series of detailed illustrations.

He published his conclusions in his usual “pompous and didactic” style with a series of detailed illustrations.

“These were clearly such revolutionary changes in the kitchen that they were immediately seized on by hundreds of people all over Europe, and the count himself suddenly became in great demand as a kitchen architect.” (Brown 170, 152)

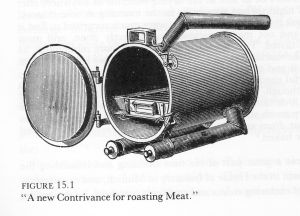

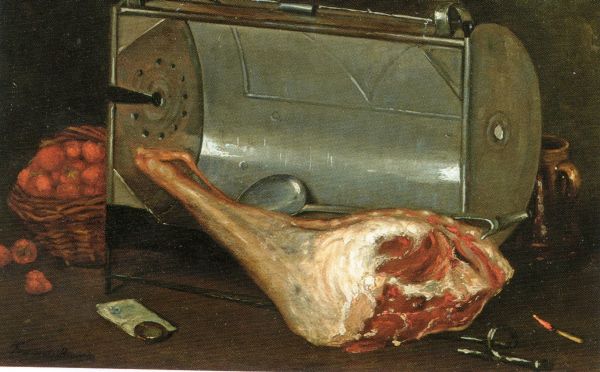

Thompson also designed an enclosed metal roaster for installation within a conventional brick oven. It included blowpipes and dampers to adjust the airflow for roasting meat slowly over a low fire. A grate astride a bath collected juices from the meat; the water prevented the drippings from scorching. Thompson calculated that his metal oven used only a tenth the fuel of a traditional open fire (Brown 159), a dramatic increase in efficiency even allowing for his customary exaggeration.

According to Brown, this “Contrivance for roasting Meat” brought Thompson widespread fame; “hundreds of the roasters were installed all over Europe and America, and in old New England houses they can still be found unchanged from his original designs.” (Brown 158)

Thompson also designed all manner of pots and pans for use on (or in) his ranges, including the first percolator for coffee, and was the first manufacturer to give some of them holes on their handles for hanging.

“Constructing kitchen boilers, stewpans, etc., is a matter of so

much importance that I cannot pass over it in silence.”

9. A sort of enlightened despot.

These and other innovations arose from one of Thompson’s most successful endeavors in Munich, his operation of the House of Industry. With a typical twist of intrigue, Thompson stole the idea, and the lucrative sinecure that accompanied its implementation, from an infuriated Italian rival who had first been granted the position. (Brown 124-25)

It was no small undertaking:

“Bavaria was famous at the time for its hunger, its idleness, and its crime. Poverty was so rampant it was estimated that one out of every thirty people in Munich was a beggar, and criminals were said to be as numerous as beggars.” (Brown 99)

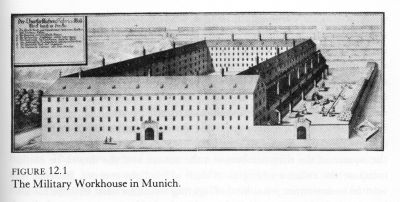

To combat the problem, the Electorate established the House of Industry, a ‘military factory’ or workhouse, to employ, feed, house and, a previously proscribed policy, pay the destitute for their work.

The House of Industry was not known as a military factory for nothing. Thompson’s immediate impulse on assuming the office of adjutant general was to determine the costs incurred by the threadbare Bavarian army and the cost required to make something (if not necessarily an effective operational force) of it.

Thompson found that the army’s biggest discrete expense was clothing. Not artillery, nor ordinance, small arms, horses or their fodder as in other armies; such was the state of the Bavarian ‘force.’

Expense was one thing, utility another, and Thompson set about considering both. He promptly invented a ‘cylindrical passage thermometer’ and used it to determine that the amount of insulation any given fabric provides is a result of the air entrapped in its threads. He attempted to apply his discovery to weaving a cloth efficient for the purposes of the Bavarian army but found neither manufacturer nor workforce able to meet his specifications. (Thomas 14)

To solve this practical problem, Thompson hit upon a simple, salutary solution: “All the beggars and their wives and children were employed in making uniforms for the Bavarian Army.” (Thomas 14) His chosen means of production was a typically elegant and amoral solution that earned Thompson a handsome profit from the kind of puzzle he enjoyed solving.

What Thompson called “mendicity” was rife in Munich. One in thirty adult inhabitants of the city was ‘mendicant,’ and a reason why the number of beggars equaled the number of criminals was the fact that many of the beggars were criminals, “able-bodied cadgers” who used “scuffed-up children to prey on public sympathy, and who had developed an elaborate system of mooching food from merchants, which they would then sell to other shopkeepers at a profit.” (Thomas 14; Food & Think 1)

The criminal ‘codgers,’ the drifters and vagabonds, found themselves forcibly installed at the workhouse; Thompson callously had ordered his army to perpetrate the first roundup at New Year’s because he knew that the poor caroused in the streets on the day. (Brown 125) Once installed, however, the inmates found something like a new world.

Even if the system Thompson developed only could operate at maximum efficiency in an autocracy like the Elector’s Munich, it relied on incentive as well as coercion. Thompson’s target may have been the despicable rather than deserving poor, but honest people could enroll at the House of Industry of their own volition, and did.

The workhouse was kept clean and was, in comparison to many poor dwellings, comfortable. These humane practices flowed from a syllogism that was innovative, not to say previously unthinkable, in Bavaria:

“To make vicious and abandoned people happy, it has generally been supposed necessary, first, to make them virtuous. But why not reverse this order! Why not make them first happy, and then virtuous! If happiness and virtue be inseparable, the end will be as certainly obtained by the one method as by the other; and it is most undoubtedly much easier to contribute to the happiness and comfort of persons in a state of poverty and misery than by admonitions and punishments to reform their morals.” (Brown 126 quoting Thompson)

Cuvier recalled in his eulogy of Thompson that although his colleague worked hard for decades to improve the lot of the poor, and the simple comforts of all social strata, “it was without loving or esteeming his fellow creatures that he had done all these services.” (Thomas 12 quoting Cuvier) Thompson himself wrote, if in one of his darker moods, that

“I hate mankind with a most perfect hatred, and so deeply rooted is my aversion to them, that if I were to see a brute animal stand up on his hind legs I should run away from him.” (Brown 164, quoting Thompson)

The happiness of inmates at the House of Industry was strictly incidental to a different goal. Thompson calculated that happy people would be less inclined to risk breaking the law if rewarded with creature comforts and pocket money, and so garner him greater profits.

People who tried to work got paid “whether or not they produced usable goods;” but a piecework pay scale encouraged them to work with diligence. At least as important, the very real threat of theft, cheating and fraud by a potential criminal element within the walls was kept in check. The workhouse was safer than the street. (Brown 126-27)

Ill, weak, underage or simply inept inmates were accommodated, provided they failed a medical examination or demonstrated their incompetence, but the able-bodied who would not work did not eat. In a nearly sadistic turn, Thompson imposed a routine on the younger inmates empty enough to require them to sit still for long stretches “so that they would be enticed by boredom to prefer work.” (Food & Think 2)

If the regimen was relatively enlightened, it was hard. Thompson expected his charges to work from twelve to fourteen hours a day. That presented a profound problem in a pre-electric age because, except in summer, the parameters of the workday outlasted the hours of sunlight. Rumford therefore turned his attention to illumination.

First, he invented the photometer, an instrument for measuring the intensity of light. It still bears the Rumford name. (Thomas 15) Ever the empiricist, Thompson then conducted a series of experiments on luminosity with the device. The results along with a series of tests enabled him to produce ‘smokeless’ lamps that not only did less to foul the air than contemporaneous lanterns, but also burned less fuel. (Adams)

He also conducted a series of studies to determine the cheapest way of feeding his charges. Soup was so efficient that he became obsessed with it, and served the version he developed at every meal. Recipes for Rumford soup--made from barley, old beer, dried split yellow peas, potatoes, salt and vinegar--still float about the internet even if they are relatively difficult to find.

While “the profits from his poorhouses increased as his costs decreased,” the tireless Thompson also monitored the inmates to ensure that they got enough to eat so their productivity did not decline. Brown,  whose admiration for Thompson’s scientific accomplishments does not blind him to his subject’s ghastly character, is not particularly judgmental on this score:

whose admiration for Thompson’s scientific accomplishments does not blind him to his subject’s ghastly character, is not particularly judgmental on this score:

“Because lack of food for generations had been the lot of serfs and beggars, their bodies were stunted from malnutrition, and they were grateful just to get regular meals. In fact, they looked on Rumford as their benefactor and savior, and the count was very proud of this.” (Brown 161)

So, oddly enough, the system seemed to work. As usual, Thompson published a glowing appraisal of his program, this time in the guise of a guidebook for other cities. (Food & Think 1)

10. No embarrassment about riches.

His marketing campaign was so successful that when Thompson retreated from Munich for Britain, he found himself in great demand as both designer and reformer.

“One thing emerges clearly from Rumford’s intense activity as he dashed about England, Scotland, and Ireland building and rebuilding kitchens, stoves, and fireplaces and advising local governments all over Britain on how to care for the poor and needy--he was being well paid for his efforts, and was becoming very wealthy.” (Brown 171)

It would be more accurate to note that he was becoming even wealthier. Thompson had lived large in Rumford, Munich and London, engrossed in the culture of display that cemented social and political power in an age of elite excess.

Once again Thompson would display his dual nature, at once selfless and self-serving, in the way he decided to utilize his fortune. He did not hesitate to traduce Americans as foolish bumpkins or seditious anarchists when it suited the moment, but appears never to have shed the perception of himself as a New Englander. Over a decade after his last stay in North America, he had chosen and kept ‘Rumford,’ the former name of that New Hampshire town where he found his first fortune, for his cherished Holy Roman title.

At various points he hoped to retire to New England, but meanwhile wanted to keep an iron in the fires of Westminster. He therefore donated the astonishing sum of $5,000 each to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and the Royal Society, which more than a decade earlier had made him a Fellow for a pathbreaking paper on the properties of gunpowder. Each gift funded a prize for exemplary scientific research in the fields of heat and light. The bequest was contingent on the casting of a medal bearing Thompson’s image for presentation to the recipient; no point in making an investment that goes unremembered.

It was not enough to spare him several disappointments. Notwithstanding his stint as a spy against the Continentals and his antics at Huntington, Thompson saw no reason why, in 1799, he should not leverage the ‘martial’ record he compiled in North America and Bavaria into a position as commandant of the new United States Military Academy at West Point. This time his uncanny luck just failed him. After President Adams approved Thompson’s application, in yet another demonstration that a revolutionary does not always a ruler make, Rufus King did some research that uncovered the eminent scientific philosoper’s Loyalist sympathies and got the appointment rescinded.

That same year, Thompson nearly landed another appointment that should have been as unimaginable as the West Point position. For some reason Carl Theodor continued to harbor an affection for Thompson after allowing him to take the fall for his principality’s military enfeeblement. He therefore proposed as a parting gift the installation of Thompson as Bavarian Ambassador to the Court of St. James, either unaware or unconcerned about his putative emissary’s covert treason against the British Crown. After an unaccountably warm reception of Thompson by Lord Canning, then Foreign Secretary, an incandescent George III vetoed the appointment.

Luck immediately intervened in the person of Sir Joseph Banks, the influential president of the Royal Society, who asked Thompson to draft the proposal for a lavishly endowed Royal Institute. He knew Sir Joseph as well as a number of other eminent social reformers and philanthropists, including Henry Cavendish (“the wisest of the rich and richest of the wise”) and William Wilberforce, the great abolitionist. They and other luminaries, including as it transpired a duke, six earls, seven lords, a bishop, eighteen Members of Parliament and eleven knights, would fund the foundation as permanent proprietors.

Luck immediately intervened in the person of Sir Joseph Banks, the influential president of the Royal Society, who asked Thompson to draft the proposal for a lavishly endowed Royal Institute. He knew Sir Joseph as well as a number of other eminent social reformers and philanthropists, including Henry Cavendish (“the wisest of the rich and richest of the wise”) and William Wilberforce, the great abolitionist. They and other luminaries, including as it transpired a duke, six earls, seven lords, a bishop, eighteen Members of Parliament and eleven knights, would fund the foundation as permanent proprietors.

The organization he described was the embodiment of his lifelong approach to scientific pursuits:

“ ….a Public Institution for diffusing the knowledge and facilitating the general introduction of useful mechanical inventions and improvements, and for teaching by courses and philosophical lectures and experiments the application of sciences to the common purpose of life.” (Thomas at 18 quoting Thompson)

Practical invention, not theoretical research, was his vision for the Royal Institution, and as its first President, Thompson implemented it with his customary “energies and acumen.” He drafted a constitution, obtained a Royal Charter and designed the institute’s premises. These reflected his enthusiasms to include a kitchen, laboratory, lecture hall, model rooms for the display of mechanical innovations, workshops and later a library and reading room. (Thomas 18)

Thompson took complete control, hiring eminent researchers and setting a punishing pace: “When the dynamic Rumford was present at the Institute in Albemarle Street the whole place hummed with a feverish activity.” (Thomas 18)

11. Disgrace again, and denouement.

He would last less than two years, brought down by a clash over the focus of the institute and his impossible personality. The proprietors favored an emphasis on theoretical research over practical pursuits and became alarmed at Thompson’s profligate use of their funds, while his colleagues predictably enough found him “dictatorial and overbearing; they resented his bullying and felt that his whole manner was irksome.” (Thomas 18)

So many important people had by now become so hostile to Thompson that he found life in London untenable and sailed once again for the continent. In Paris he met an ecstatic reception from various salonniers, Talleyrand and Napoleon himself, who enjoyed collecting scientific philosophes but later cooled on the English officer and spy. Some years later the Emperor would expel Thompson for a time from France.

Meanwhile Thompson had commenced an affair with another wealthy widow, Madame Lavoisier, whose husband, an eminent scientist in his own right, had fallen victim to the Terror. Eventually they overcame the Emperor’s objections, married and returned to Paris, but the couple fell out. “Acrimonious and vituperative rows between them flared up in public to the embarrassment of their hosts or guests;” their fights became so famous that they attracted the attention of Fouché, the fearsome Napoleonic prefect of secret police (Brown 289)

Thompson complained that his wife, whom he called a “Dragon,” even “goes and pours boiling water on some of my beautiful flowers.” (Thomas 19, 24n.20 quoting Thompson) Madame also engineered the count’s ostracism from fashionable society while his own “haughty, egotistical and insulting” response to criticism alienated his scientific colleagues. The couple separated within two years, in 1807.

He then decamped to the suburb of Auteuil, where nothing really changed but the antagonists; “his personal relationships were miserable” but his research continued to break the bounds of scientific knowledge until his sudden death seven years later. (Thomas 25n.21)

12. The horror of genius.

Genius, sociopath

Thompson has proven an elusive character. Nicholas Delbanco, who in 2008 wrote a novel about him called The Count of Concord, has said that he “had literally hundreds of pages of prose about this man, and no sense of what made him tick, or what made him behave the way he behaved in the world.” Delbanco believes that “he was one of those meliorists, one of those world-building, outward-facing, I-can-fix-the-lot-of-mankind-types” and yet “there was nothing that we would describe as remotely self-conscious or self-aware.” (Short 4)

That, ironically, sounds more like a failure of imagination by Delbanco the writer of fiction than a decent appraisal of Thompson, who might better be described as a highly functioning genius and sociopath. A fusion of the rational and irrational, he represents the quintessential Enlightenment polymath in his devotion to the empirical pursuit of order and explanation, but was sufficiently self-aware to understand that an unhinged passion ruled his consciousness:

“The ardour of my mind is so ungovernable that every object that interests me engages my whole attention and is pursued with a degree of indefatigable zeal which approaches to madness.” (Thomas 12 quoting Thompson)

Thompson indisputably had luck, but if his lack of scruples placed him in the way of harm, the same amorality coupled with energy and intellect created a good deal of it. The mad zeal countenanced no brake, not intellectual, political or moral, and so the experiments and learned papers, the sexual and partisan promiscuity, the social and military innovations (and occasional atrocities), not least the self-promotion and misanthropy, accelerated to manic velocity.

13. The shrine of sorts in a hall of ivy.

Brown, the objective biographer, became sufficiently obsessed with his subject to see that he secured for him an enduring if eccentric memorial. It is a mosaic allegory depicting Thompson and his achievements. Figures and other images representing Thompson’s humanitarian and scientific endeavors, including graphics derived from his drawings, surround a tiled rendition of the Peale portrait.

Thompson holds one of his lamps to the left, his biography by Brown (Dartmouth class of ’35) to the right; it rests on two utensils that the count designed. Surrounding images include his fireplace; the Gillray caricature of him basking bottomless before it; the metal roaster, cooking chicken and fish; and a number of more obscure references.

Adams believes that three fish in the lower right corner of the mosaic symbolize the United States, Britain and Bavaria; “a tree illuminated by the sun” is said to represent Thompson’s “introduction of farming by prison inmates to grow their food.” There are more drawings of his kitchen implements, some of the scientific apparatus he devised and a burly smith boring a gunbarrel to commemorate the experiments about the nature of heat. (Adams 4)

The confection, completed in 1970 for Brown’s own house, now resides in the Fairchild Physical Sciences Center at Dartmouth College, where it has mystified onlookers since 1992. The late date of installation for something so artistically unfashionable, commemorating someone so flawed, strikes a unique note. It speaks nearly as much to the eccentric culture of Dartmouth as to the achievements of so ambiguous a figure as Thompson.

14. A lasting legacy?

It is doubtful that Thompson would have considered the mosaic an adequate tribute. He craved riches, fame and stature, and ached for a lasting legacy.

To ensure that posterity kept the appropriate appreciation for him, Thompson planned “an autobiographical sketch full of praise and wonder that any man could do so much good for society,” for illustration with a flattering engraving he reported “is thought to be a strong likeness.” (Brown 251) Uncharacteristically, however, he failed to finish it.

In another conventional Georgian bid for immortality, Thompson sat for Rembrandt Peale and Thomas Gainsborough, the sole American by birth he ever painted. Thompson would be pleased that the Gainsborough portrait hangs in the Fogg Museum at Harvard.

On his death he endowed the university with the Rumford Chair in physical science; during the nineteenth century a grateful occupant invented baking soda and named the commercial product for the count. Nothing if not practical, Thompson might not mind that so homely and universal a substance enshrines his memory after a fashion, but would have hungered for more. And, once again, we encounter a certain duality, this time in the nature of his legacy.

Much, it would seem, may be forgiven a genius, and that has been the case for Thompson. In 1867, the citizens of Munich, in fond memory of the Military Factory and grateful for the English Garden, erected his statue; a copy now stands in his hometown of Woburn, Massachusetts, while Harvard has found no reason to renounce the chair he bequeathed it.

Writing in 1998, however, another occupant of the Rumford Chair noted that his benefactor’s “obscurity” in North America was “widespread” (Thomas 11) and it is equally doubtful whether many people other than academic scientists anywhere know a thing about him.

In reality he is all around us. Franklin Roosevelt considered Thompson along with Franklin and Jefferson one of “the three greatest intellects America ever brought forth.” (Thomas 11 quoting Roosevelt [but without citation]) Every other year two eminent researchers receive a Rumford medal. Humphry Davy, the genial genius Rumford had the foresight to install as his successor at the Royal Institution, Faraday and Pasteur are among those who have gotten medals from the Royal Society; Edison, Fermi and Edwin Land of Polaroid fame from the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

|

|

Then there are the innovations and inventions. In addition to all the others, they include, among other things, the double boiler; a soup kitchen, organized at sufficient scale that would set the pattern for relief of malnutrition and even famine; industrial furnaces of higher efficiency than their predecessors; advances in the ballistics of light arms and heavy guns; an innovative forty gun frigate design with a sharp deadrise that would have both prevented ‘hogging,’ or sagging of the vessel under the stress of its own weight, and increased its speed if it been built; and thermal underwear.

Vanardy apparently refers to this last item in claiming without citation that Thompson “invented a curious kind of masculine pant with a fly down the front… and up the back! The man was a gay genius.” (Vanardy 7; ellipses in original) Whether or not that is the case, the garment would have been handy whether its wearer preferred to give or receive.

Notwithstanding all the evidence of Thompson’s accomplishment, his greatest contribution was not what he discovered or created but how he went about his work. As Thomas, ever acute, explains:

“In an age when the natural philosopher tended to belittle the engineer and treat him as an artisan or common labourer, and the inventor, in turn, regarded the natural philosopher as an intellectually snobbish dreamer, Rumford wrote, argued and practiced--well ahead of his contemporaries--a scientific philosophy which cogently stated that fundamental research in a problem is a prerequisite to technological development.” (Thomas 12)

That breakthrough in methodology helped unlock the first industrial revolution.

15. An abundance of errors.

It is with no little regret that we inevitably return to the Twenty-first century and Pudding: A Global History. Other than that percolator and the field kitchen, Quinzio misses much that matters about Thompson, and much else. She refers to his use of a pudding bag, and includes a quotation that refers to one, but never explains what it is or that it was a transitional vessel between cloth and basin. Another transition, the evolution from Medieval puddings combining sweet and savory ingredients to puddings identifiably sweet or savory during the eighteenth century, also goes unremarked.

Quinzio discusses one of the later composite puddings, Robert May’s 1685 recipe for “Puddings of blood after the Italian fashion” from his Accomplisht Cook, in confused and confusing terms. She does not say so, but May is a major figure in English culinary history. In Alan Davidson’s assessment:

“If a poll were to be taken among those who have studied the history of cookery books in the English language--a poll intended to identify the ‘top ten’ or the ‘six all-time greats’ or whatever--I dare say that Robert May would come as close as anyone to attracting unanimous support.” (May “Forward” 7)

May makes his ‘Italian’ pudding from pork blood, grated cheese, grated bread (he specifies “manchet,” an ancient English roll that still lurks in the American south), “sweet herbs,” suet, “nutmeg, pepper, salt, ginger, cloves, mace, cinnamon, sugar, currans, eggs, &c.” (May 26) Quinzio speculates that inclusion in the pudding of “the grated cheese set it apart and, apparently, made it Italian, although he didn’t specify the type of cheese.” (Quinzio 28)

Based on the omission, Quinzio places May among other unnamed cooks who “often kept their own particular recipe a well-guarded secret.” (Quinzio 28) This is both anachronistic and illogical.

The Accomplisht Cook was, according to Davidson, “the first full-scale English cookery book” (May “Forward” 7) and, in common with virtually every cookbook written before Eliza Acton’s breakthrough in 1855, it not only dispenses with measurements for a varying proportion of ingredients in each recipe but also frequently describes them only in the most general terms. May was a professional cook and published writer who wanted to sell books; secrecy was antithetic to his purpose. Sabotage of his own recipe by omission hardly was likely to boost sales, so it is unlikely he sought consciously to conceal anything.

Does the addition of cheese ‘make the pudding Italian,’ as Quinzio asserts, and if so, should the cheese in question be Italian? May describes several of his puddings as “Italian,” and while some include cheese, others do not. Other ingredients and some of the techniques he uses in ‘Italian’ recipes also appear in recipes without the label, so cheese does not an Italian pudding make.

Does the addition of cheese ‘make the pudding Italian,’ as Quinzio asserts, and if so, should the cheese in question be Italian? May describes several of his puddings as “Italian,” and while some include cheese, others do not. Other ingredients and some of the techniques he uses in ‘Italian’ recipes also appear in recipes without the label, so cheese does not an Italian pudding make.

The likelier explanation: Things Italian were fashionable things in Restoration England, and fashion sells. Chicken Florentine, for example, originated in Paris when Catherine De Medici had installed her Italian cooks in the royal palace there; the Italian reference gave cachet to the dish but did not describe its actual origin.

Nor should we conclude that May believed the addition of an Italian cheese rendered a dish Italian, for he does specify “good fat Holland cheese” for his “Cheesecakes in the Italian Fashion.” (May 290)

Other problems also arise from Quinzio’s discussion of May’s pudding. She maintains that various blood puddings were “served in fine dining restaurants” during his day, but nothing recognizably a restaurant would appear anywhere until the following century and nobody of his era would recognize the concept of “fine dining,” while the term itself is only of recent vintage.

All the inaccuracies and omissions sit uneasily with a tendency to the redundant. In a text including all of 123 pages incorporating a multitude of illustrations, serial repetition is irritating and inexcusable. The anachronistic reference to “fine dining” during the Restoration is not alone. It surfaces elsewhere, including a passage in which Quinzio claims that today, “[f]ine dining restaurants on both sides of the Atlantic are featuring savoury as well as sweet puddings.” (Quinzio 120) The incidence of savory pudding on American menus, however, ranges from scant to nonexistent.

Quinzio explains that George I was called the pudding king at page 22 and again at 57: Several times we hear that Yorkshire people like to think only they can make proper Yorkshire puddings.

Suet is misidentified as meat (it may be an animal product but, inarguably, is a fat) at page 31and again at 34; twice we are told that sometimes puddings were cooked within an intact carcass for an amusing effect. (16 and 27-28)

We hear three times that pudding was eaten as a filling first course by those of modest means to help stretch their meager servings of meat (18 and 45), the last iteration adding the obvious and awkward statement that “[d]espite the English’s [sic] reputation as great meat-eaters and the pride they took in their joints of roast beef, eating large quantities of beef was not the birthright of every Englishman.” (Quinzio 46) Perhaps it is important to explain for the dimmer reader that the poor always have been amongst us. In another statement of the self-evident, Quinzio explains that when “the basic mixtures” of a pudding are sweetened it becomes suitable for dessert.

Sometimes her language is simply inane, as in the discussion of white pudding: “Gradually, the new dish became the time-honoured one.” (Quinzio 31) Do we need a reminder that the passage of time is linear? Or, in the case of haggis: “Treated with reverence and ceremony by its aficionados, it is subjected to ridicule by those who don’t appreciate it.” (Quinzio 33) Is that not what aficionados and the unappreciative of anything respectively do?

Quinzio does get something unknown right. Haggis did originate in England, but it is problematical of her to claim it as the most famous pudding. In strictest terms haggis, cooked in gut, is not what we have defined as a pudding in modern terms, something based on pastry; but if it were, what about steak & kidney, Christmas, hasty and summer puddings?

On summer pudding, Quinzio gushes that “[t]oday, summer pudding is one of Britain’s most delightful desserts.” As opposed to yesterday, when it presumably was revolting? Unlikely; the constituents remain unchanged. No matter; it finally “has proven fit for a queen” because it appeared on a 1982 dinner menu for Elizabeth II (“for,” Quinzio helpfully notes, “dessert”). (Quinzio 85)

Her editor might have caught any of these lapses, and others as well. Agatha Christie’s Mystery of the Christmas Pudding appears italicized in one place and within quotation marks elsewhere; the caption to an illustration depicting Royal Marines aboard a man o’ war describes them as “on the deck” when the steep stair beside them and dark cast of the print demonstrate that they are sitting in the gloaming of the hull.

The bibliography of Pudding is inadequate for the task to hand; a number of authors or titles mentioned in the text are not identified in full. Many writers central to preservation of the pudding tradition are omitted; no Ayrton, no David or Grigson, Norwalk nor more. And yet the index does, however, include an entry for ‘Buddha’ because, apparently, the divine glutton likes rice pudding.

Quinzio includes an appendix of pudding recipes. Summer as well as steak & kidney puddings, and haggis for that matter, make no appearance.

Sources:

C. Raymond Adams, “Benjamin Thompson, Count Rumford,” The Scientific Monthly 71, No. 6 (December 1950) 380-86

Anon., “Count Rumford and the History of the Soup Kitchen,” Food & Think (December 2010), http://blogs.smithsonianmag.com/food/2010/12/count-rumford-and-the-history-of-the-soup-kitchen.html (accessed 4 December 2013)

Sanborn Brown, Benjamin Thompson, Count Rumford (Cambridge MA 1981)

Buckley Rumford Fireplaces, Count Rumford, www.rumford.com/Rumford.htpml (accessed 4 December 2013)

G. Cuvier, Recueil des éloges historiques (Paris 1861)

Cate Garrison, Choice Cuts of Lamb (Raleigh 2008)

Walter Gratzer, Terrors of the Table: The Curious History of Nutrition (Oxford 2005)

Judith & Marguerite Herman, The Cornucopia, Being a Kitchen Entertainment and Cookbook (New York 1973)

Allen King, “Count Rumford, Sanborn Brown, and the Rumford Mosaic,” Dartmouth College Library Bulletin (April 1995)

Egon Lehrburger [as ‘Egon Larsen’], An American in Europe: The Life of Benjamin Thompson, Count Rumford (New York 1953)

Robert May, The Accomplisht Cook, or the Art & Mystery of Cookery (London 1685; Prospect Books facsimile, Totnes, Devon 2000)

Jeri Quinzio, Pudding: A Global History (London 2012)

Hugh Rowlinson, “The Contribution of Count Rumsford to Domestic Life in Jane Austin’s Time,” Persuasions On-Line v. 23 No.1 (Winter 2002), www.jasna.org/persuasions/on-line/vol23no1/rowlinson.html (accessed 23 January 2014)

Brian Short, “Interview with Nicholas Delbanco, The Count of Concord,” http://fictionwritersreview.com/interviews/interview-with-nicholas-delbanco-the-count-of concord (accessed 22 January 2014)

J. M. Thomas, “Sir Benjamin Thompson, Count Rumford and the Royal Institution,” Notes and Records of the Royal Society Journal on the History of Science 53 (1) (1999) 11-25

Varick Vanardy, Jr., “Gen. Benjamin Thompson, Count Rumford: Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy,” The Gay Review (Boston 1990) 12 et seq. (accessed from www.rumford.com/gayRumford.html on 4 December 2013)