A note on the Peninsular & Oriental Steam Navigation Company.

Since the first regularly scheduled packet, James Monroe, plied the Atlantic in 1818, ship owners have tried to distract their passengers from the rigors of the crossing, and even to delight them, with the quality of their food. No line offered its customers more in the way of this delight than the venerable Peninsular and Oriental Steamship Company. (Sway 4-5)

According to its official history, the antecedent of the P&O Line dates to 1815, when a Scottish veteran of the Royal Navy and an English shipbroker began to charter ships for the journeys between Britain, Portugal and Spain.

The Union of two kingdoms, but England’s on top, at least of the flag.

The Union of two kingdoms, but England’s on top, at least of the flag.

In a further symbol of Union, an Irish shipowner and former Royal Navy captain joined them in 1837 to purchase four ships of their own and form the P&O, but minus the ‘O.’ They continued to ply trade routes between the Peninsula and United Kingdom and, in a stroke of political expedience, supported the Legitimists against their liberal challengers during wars of the 1830s.

The Union of three kingdoms… and England’s still on top of the symbolic pile.

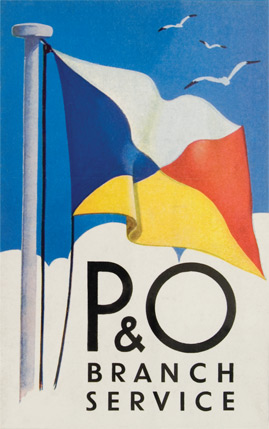

The crowns of both Spain and Portugal rewarded this fealty with “concessions and privileges,” including the right to fly their royal standards. This had vexillary as well as economic impact, for “[t]o this day the P&O’s house flag quarters the red and yellow of the former with the blue and white of the latter.” (Taste 9)

A flag of equals, sort of.

By 1837 our triumvirate had extended its reach to Gibraltar and, now as P&O itself, by 1839 to Alexandria, then Bombay by 1842, down to Ceylon in 1844, over to Shanghai by 1846 and into the Antipodes by way of Singapore in 1852. It seems that during its Victorian heyday, the business was an enlightened one that did well by doing good, to both its workers and customers. British officers ran the ships, “but local labour was always used and this tradition [was] carried on” at least as late as 1977. The Scottish founder established, in the best private Reforming and Improving way, the P&O “Provident and Good Services Fund” at midcentury to assist its employees. (Taste 9)

The largesse extended to the food that P&O fed its passengers. “It is not the first object of your work to keep down expenditure,” the company maintained in its 1908 ‘Memorandum for the guidance of Pursers and Stewards-in-charge of Victualling and Management,’

“but it is your first duty to see a table of superior quality maintained on board your ship, and your passengers thoroughly well satisfied…. It is the wish of the Directors that you should continually seek to improve the table arrangements on board your ship.” (cited at Taste 9)

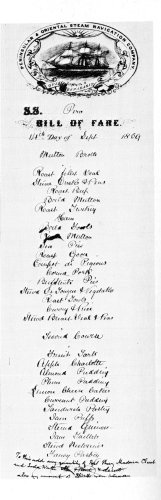

We might be forgiven a degree of skepticism, but that would appear misplaced. What this instruction in extravagance meant may be discerned from P&O ships’ menus. One dated 14 September 1859 from the SS Pera included mutton broth (it seems they always did include it) followed by a selection of seventeen main courses, including such traditional British preparations as duck stewed with peas, roast goose, sea pie… and curry. The selection of desserts numbered twelve. “To this add any quantity of Port, Sherry, Madeira, Claret, and soda water, ale & Stout & desert [sic] also any amount of Spirits you please.” In other words, drinks were free.

The Pera menu predates the onset of service ‘a la Russe,’ which remains the ordinary sequence of dining today, in which a starter precedes a single main course followed by dessert and, for the dwindling Old School, some cheese or a savoury. Not so in the earlier nineteenth century, when various platters--like those seventeen on board Pera in 1859--were served together. Diners could help themselves and their colleagues to as many of the foods as they liked.

Neither the selection available nor this manner of service differs at all from the way that officers in the royal Navy dined aboard warships during the ‘Age of Nelson,’ as we demonstrate in the critical, although curries then may have been restricted to the East India Station. (Macdonald, passim) Even ‘Corned Pork,’ or salted pork, a staple of all Napoleonic navies, still shows up half a century later on the menu of the Pera.

In part, the attention that P&O lavished on its galleys was driven by market forces, although they cannot explain the line’s culinary preeminence among its contemporaries. In any event, however, it would be wrong to forget the esteem in which the more prosperous of the nineteenth century British held their food. Writing about travel during this Imperial apogee, Boyd Castle explained to his readers in 1937 that the “British traveler then (like very many now) only considered British dishes and cooking as good; and had no time for foreign ‘kickshaws’--except that, in the liners of the P&O, even in European waters, dishes of Indian curries… were from the first regarded as one of the essential and never-to-be missed courses.” (Castle cited at Taste 10)

We find comfort, even charm, in the continuity of these maritime foodways that prevailed for over a century. Something about the tradition of curries aboard British vessels plying European waters appeals to us too, the recognition by a confident nation of its culinary exceptionalism.

Recipes for duck with peas (and lettuce), sea pie and a P&O korma appear in the practical.

Sources:

Boyd Castle, A Hundred Year History of the P & O (London 1937)

Theodora FitzGibbon, A Taste of the Sea (London 1977)

Janet Macdonald, Feeding Nelson’s Navy: The True Story of Food at Sea in the Georgian Era (London 2004)

John Malcolm Binnin, The Sway of the Grand Saloon: A Social History of the North Atlantic (New York 1971)